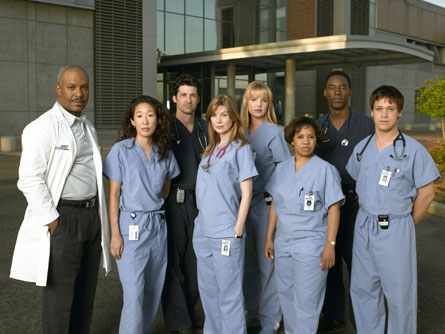

- Grey’s Anatomy

This repost by Rachael Johnson appears as part of our theme week on Women and Work/Labor Issues.

Noam Chomsky recently observed that America is engaged in “a long and continuing class war against working people and the poor.” I would add that American popular culture does not, for the most part, represent poor or working-class American citizens. US television shows and movies about less privileged people are exceptionally rare. This lack of representation is becoming increasingly indefensible in the face of acute–and expanding–economic inequality. It is also a vital feminist issue as women are still poorer than men in the United States. The US government itself released a report in March 2011–the “Women In America” report–showing that a wage and income gender gap between men and women still exists in the 21st century. Poverty rates for less advantaged women are higher because they are in low-paying occupations and because they are often the sole breadwinner in their family. There are stories behind the figures, of course, but they are seldom told on the screen. Clearly, it is time for filmmakers of all backgrounds to address this unjust and frankly absurd lack of representation. The issue should also, of course, be of interest and concern to both critics and consumers of American popular culture.

- Monster

Of course, it goes without saying that there are not nearly enough American movies with female protagonists and characters in general. Even less common, however, are features with less advantaged women. An arbitrary list of films with female protagonists and important characters covering the last decade might include Lost in Translation (2003), The Kids are Alright (2010), Black Swan (2010), Under The Tuscan Sun (2003), Up in The Air (2010), Julie and Julia (2009), Secretariat (2010), Eat Pray Love (2009), Bridesmaids (2011), Sex and The City 1 (2008) and 2 (2010), The Devil Wears Prada (2006), The Holiday (2006), Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2008) Fair Game (2010), Young Adult (2011), Zero Dark Thirty (2012), Stoker (2013), Side Effects (2013) and Gravity (2013). Clearly, all these movies are about professional and/or privileged women.

The heroines of contemporary American television are, also, for the most part, professional, upper-middle or upper-class women. Over the past decade, there have been a fair number of US TV shows revolving around the lives and careers of doctors, surgeons, medical examiners and lawyers. Damages, Gray’s Anatomy, The Mindy Project, Body of Proof, Bones, Private Practice and The Good Wife are among them. Currently, there are also shows depicting the lives of women who work for, or have a history with the US government, such as Veep, Parks and Recreation, Homeland and Scandal. The heroines of 30 Rock and Nashville work in the entertainment industry. It was a similar scene, of course, in the late 90s and early part of the Millenium when shows like Sex and the City and Desperate Housewives enjoyed mass popularity.

My point is not to knock the shows and movies cited. Some are interesting, stylish and entertaining, and a number have compelling female protagonists. It is, also, of course, essential that we see female characters make their own way in professions traditionally monopolized by men. They reflect social change as well as inspire. It is equally essential that women of power are portrayed on the big and small screen with greater frequency as well as with a greater degree of complexity. American films and television programs should not, however, block out the lives of working-class and poor women. So many stories, struggles, journeys and adventures, remain unacknowledged and untold. It is a strange and troubling thought that contemporary American audiences are simply unaccustomed to seeing interesting, strong and resourceful working-class women. Whether ordinary or extraordinary, working-class women of all races and backgrounds, need greater representation.

- Silkwood

I am, of course, aware that the term “working class” is rarely used in American public discourse. The term “middle class” is, in fact, used to refer to average Americans. The definition of “middle class” is, in fact, quite a fuzzy one but that does not stop US politicians from using it. For many non-Americans, this is a curious thing. Although the US definition of “middle class” is bound up with the meritocratic ideals of the American Dream, it ultimately represents a denial that class itself exists. To quote Chomsky again, it is a deeply political tactic used to mask social division and economic inequality: “We don’t use the term ‘working class’ here because it’s a taboo term. You’re supposed to say ‘middle class,’ because it helps diminish the understanding that there’s a class war going on.” This article specifically refers to the lack of representation of working-class and poor women on the screen. I am talking about the lives of waitresses, factory workers, maids, cleaners, cashiers, childcare workers, married home-makers and single mothers as well as those on the margins of society.

I am also fully aware of the eternally repeated claim that American audiences do not like TV shows or movies about poverty and working-class life because they find them just too damn depressing. Let’s take a look at that claim. Firstly, we have to ask ourselves who’s making it. To be blunt, it smacks of privilege and complacency. Who’s the American audience in question anyway? Advantaged viewers? And what about working-class audiences? Do they not want to see their lives represented on the screen? Surely American popular culture should not merely provide narcissistic identification for the comfortable and well-heeled. Behind the contention lies the implication, of course, that working-class life is invariably depressing. This is patronizing and, frankly, offensive. Although poverty should never be romanticized, both American television and cinema should recognize that humor, love, and culture are all part of life for less privileged people. The fact that I have to even make this ridiculously obvious point is an indication of the way millions of people been obscured from the national narrative of the United States. The powers that be–and their pundits–should also, in any case, not make assumptions about what movie or show will be a great critical or commercial success. Nor should they patronize contemporary American audiences about what they can or cannot handle. Many of the best-loved shows of the Golden Age of TV have featured unsanitized, hard-hitting scenes showing human life in all its ugliness and glory. Can’t poverty be processed by TV audiences? Will class always be unmentionable?

- The Good Wife

We also have to ask if there is strong historical evidence to back up the claim. A quick study of American films and television shows over the last 40 years or so shows that working-class female characters have, from time to time, actually been celebrated in popular culture. Roseanne is, of course, the most famous small screen example. Featuring a fully realised working-class female protagonist, the hugely popular, award-winning sitcom ran from 1988 to 1997. Roseanne was, in fact, exceptional in that it gave the world a ground-breaking TV heroine as well as a funny and compassionate portrait of an ordinary, loving blue-collar American family. Memorably played by Roseanne Barr, the matriarch of the show had warmth and wit as well as great strength and character. She was that most uncommon of creatures on US television: a working-class feminist. I’m sure I’m not alone in saying that America and the world needs the wise-cracking words of characters like Roseanne more than ever. A cultural heroine is currently badly needed today to deflate the criminal excesses of corporate masculinity.

- 2 Broke Girls

In the 70s and 80s, there were even films about heroic female labor activists. Take Norma Rae (1979) and Silkwood (1983). Drawing on the real life experiences of advocate Crystal Lee Sutton, Norma Rae (1979) tells the tale of a North Carolina woman’s struggle to improve working conditions in her textile factory and unionize her co-workers. Silkwood (1983) chronicles worker and advocate Karen Silkwood’s quest to expose hazardous conditions at a nuclear plant in Oklahoma. Both films feature well-drawn, dynamic, complex female protagonists, vital, persuasive performances and compelling story lines. Meryl Streep is customarily exceptional as Karen Silkwood while Sally Field won a Best Actress Oscar for Norma Rae. The latter’s “UNION” sign is, in fact, the stuff of cinema history. Although these narratives center around the individual–in a classically American fashion–they are, nevertheless, about women who are fighting for others. There have been other female labor organizers in American history, of course. Why are filmmakers not interested in their extraordinary careers? Why can’t there be biopics about women like Dolores Huerta? And tell me this: Why is no one interested in the pioneering life of Lucy Parsons?

- Wendy and Lucy

A few mainstream films have endeavored to expose brutal maltreatment of working-class women in American society. Based on a true story, The Accused (1988) is about the gang rape of Sarah Tobias (superbly played by Jodie Foster), a waitress who lives in a trailer home with her drug dealer boyfriend. Jonathan Kaplan’s drama is actually quite unusual for an American film in that it acknowledges the factor of class in the victimization of its female protagonist. For the “college boy” rapist in particular, Sarah is nothing more than “white trash.”

Have there been more historically recent exceptions to the bourgeois rule? Over the last decade or so, there have been a small number of films that have featured disadvantaged female protagonists. Patty Jenkins’ Monster (2003) is a striking example. Monster is based on the real-life story of Aileen Wuornos, a street prostitute and killer of seven men in Florida in the late 80s and early 90s. Unusually, sexuality, gender, and class intersect in the film. A sex worker in a relationship with a young lesbian woman, Wuornos defied the gender and sexual norms of her time and place. Money–the lack of it–is also seen to play a pivotal part in her fate. Jenkins paints Wuornos as an unstable, brutalized woman wounded by past abuses. Monster is a controversial film. Some argued that provided a too sympathetic interpretation of the convicted killer. Was Wuornos an unbalanced, victimized woman or simply a cold-blooded psychopath? What is clear is that Monster tries to contextualize violence. Not many American filmmakers dare to seriously address the social and psychological effects of poverty and abuse in their portraits of murderers. Channeling the fractured psyche of this most marginalized of women, Charlize Theron’s Oscar-winning incarnation as Wuornos is, simply, a tour de force. Why Monster was not nominated for Best Film or Best Director tells us a great deal about misogyny and classism inside the Academy.

- Norma Rae

Clint Eastwood’s Million Dollar Baby (2004) is another well-known film also about a less-advantaged woman. It is the story of Maggie Fitzgerald (played by Hillary Swank in another Oscar-winning role), a waitress who wants to be a boxer. While its portrait of the movingly dogged and committed Maggie is greatly sympathetic, that of her family–including her mother–is deeply offensive. They are characterized as “white trash” welfare parasites. Maggie is depicted as a very different, noble creature who must cut loose from her nasty roots and class. In Million Dollar Baby, we have, in fact, a well-drawn, sympathetic female character of modest origins as well as an ideologically loaded, hateful take on working-class men and women. Maggie is a working-class girl who has been emptied of all class-consciousness. Audiences and critics alike always need, therefore, to ask themselves how less-privileged women are being portrayed on the screen and how class is being represented. They should call out discriminatory portraits.

More recently, there have been movies about less-advantaged women but they remain uncommon. Debra Granik’s Winter’s Bone (2010) is a critically successful case in point. Set in a crime-scarred community in the rural Ozarks, Winter’s Bone is the story of Ree Dolly (Jennifer Lawrence), a 17-year-old girl struggling to save her family home. Ree’s missing father, a local meth cooker, has put the family property up for his bail bond and she must find him or risk losing everything. Granik provides the viewer with a sympathetic portrait of a determined yet disadvantaged young woman at risk. Winter’s Bone never, however, drowns in sentiment. The scene where Ree surrenders her horse–she can no longer afford to keep it–is portrayed in poignant yet understated fashion. Winter’s Bone contains intimate scenes of quiet power. We watch Ree teach her younger siblings to prepare deer stew and to shoot and skin a squirrel. This is a world you rarely see in Hollywood movies. Winter’s Bone has its flaws, all the same. The skies are perpetually grey and there is an improbable lack of humor in the community portrayed. More importantly, while it depicts hardship and shines a light on rural social problems, Winter’s Bone cannot really be said to critique class or structural inequities. Its narrative is typically or mythically American. Granik’s heroine is engaged in a personal rather than collective struggle. In the end, Winter’s Bone is a tale of a tough, sympathetic individual fighting for her family’s financial security.

- Roseanne

There are other filmmakers who are interested in the lives of struggling and dispossessed women. Kelly Reichardt’s Wendy and Lucy (2008) is a deeply humane story about a young woman’s search for work in the American North West. It is a simple tale that provides the viewer with a little understanding of what life is like for a girl (Michelle Williams) who sleeps in a car, with only her beloved dog for company. Its sensitive observations and empathetic insights, in fact, make Wendy and Lucy quite invaluable. Released the same year, Courtney Hunt’s excellent crime drama Frozen River is about a store clerk who becomes a people smuggler. Its central character (terrifically played by Melissa Leo) is a strong woman who has chosen to take a criminal path to support her sons and save her home.

Working-class female protagonists remain rare, however. More often than not, working-class women play supporting roles as mothers, wives or lovers. Their characters are invariably underwritten or stereotypical. A case in point is the character of Romina (Eva Mendes), a diner waitress and lover of the male protagonist in Derek Cianfrance’s tragic though self-indulgent sins-of-the-fathers epic, The Place Beyond the Pines (2013). The purpose of Romina, it seems, is to wear a pained expression and bear witness to reactionary patriarchal sentiment. Again, we need to respond to representations of working-class women critically.

While sexual abuse and domestic violence is a fact of life for women and girls across the socio-economic spectrum, it is, arguably, more common for working-class female characters to be portrayed as victims on the screen. I am not, of course, saying that filmmakers should not shine a light on the suffering of poorer victims of abuse. What I am suggesting is that the imbalance locks less privileged women and girls into the victim or martyr role in cultural representations. As powerful a depiction of abuse Precious (2009) is, it arguably perpetuates deeply offensive classist and racist stereotypes.

- Winter’s Bone

Less privileged women are perhaps even more poorly represented on the small screen. Some may suggest that the question of money, or the lack of it, is being addressed in shows such as Girls and 2 Broke Girls. The former, of course, revolves around the personal struggles and adventures of a 20-something woman finding her way in New York. The comedy-drama, however, does not explore what it’s really like to be without money in a big city and its characters are not, of course, working-class girls with few options and no cushion. The comedy 2 Broke Girls does have a working-class protagonist. Yet while it is about women who have two jobs, and while its humor is, in part, directed at privilege, it cannot be accused of being a great satirical comedy about economic inequities. It is, in fact, both classist and racist in its humor. Are there, in fact, any contemporary US comedies that truly target economic inequality? Are there any US dramas that express anger at class divisions? What is, unfortunately, apparent is that the current Golden Age of American television does not have authentic working-class heroines.

Clearly, there needs to be a much greater representation of working-class and poor women in US popular culture. How can the lives of millions of American citizens be reflected so rarely on the screen? There should also be socially aware portraits of such women. Filmmakers should respond to the outrage of millions and confront economic inequality. They should, also, not be frightened of being political. Economic inequalities should not remain unanalyzed and unchallenged. Hardship should not be hidden but movies and TV shows that represent working-class life should capture both its joys and struggles. Working-class women need not be portrayed as angels or martyrs. Vivid, complex characters are needed. Filmmakers need to remind themselves that there have been great working-class heroines in American film and television. More stories are needed about less privileged women who work to change the lives of themselves and others. Writers and directors should portray the lives of politically active working-class women as well as the careers of great social activists. They are the stuff of great drama. The huge popularity of Roseanne illustrates that Americans have been more than willing to embrace shows about working-class life. Roseanne also showed that the lives of working-class women can be depicted with both heart and humor. Imagine, if you will, a satirical sitcom set in a Walmart-like store. If braver choices were made, and if braver filmmakers were given greater attention, a working-class feminist consciousness would be given a voice in American popular culture.