“I don’t know. It’s just the distance between life as you dream it and life as it is.” –Sheba Hart

|

| Notes on a Scandal film poster |

In Notes on a Scandal, a 2006 British psychological thriller, a web of lies and manipulations form around the relationship of two schoolteachers who live very different lives.

Told through her point of view, the film takes viewers into the mind of Barbara Covett (Judi Dench), an elderly woman whose sweet voice and grandmotherly appearance hide a cunning mind and sinister intentions. She lives alone with her cat and confides only in her journal, whose entries form the film’s narration.

Her loneliness is compounded by this narrative technique, as Barbara is often given no one to play off of and instead watches interactions from a distance, remaining an entirely closed off person with a rich internal life she only reveals in her private writing. For an older woman, whose age, unmarried status and perceived lack of attractiveness leave her virtually invisible and of no value to society, this narration allows her to express her resentment. But underneath her malice is the profound loneliness of a woman who seems to have never learned how to connect to people and to remain in their lives without manipulations.

|

| Barbara only confides her real opinions in her journal |

To a degree, her isolation is self imposed as Barbara sees the people around her, students and teachers alike, as uncultured, unwashed and unilaterally badly behaved. That she sees herself as above them is highlighted in an early sequence when she watches the children come into the school from an upper floor window. This is the scene where Barbara first sees Sheba Hart (Cate Blanchett).

Sheba’s first appearance presents a sharp contrast. She floats, very blonde and pale in a sea of dark haired students in black uniforms and the viewer’s eye, aligned with Barbara’s, is easily drawn to her. While Barbara, a through disciplinarian in dowdy clothes, fits naturally into the school environment, Sheba is alien within it. It is suggested that she has no authority over the students because she still sees herself as a young person and wants to be their friend. The film also addresses the idea of class difference which further sets Sheba, with her upperclass background, apart from the working class pupils.

The details of Sheba’s life seem comfortable enough; she lives in a large, ornate house with her much older husband (Bill Nighy–who interestingly portrayed a love interest to Dench in Best Exotic Marigold Hotel) and her two children, a teenage daughter (Juno Temple) and a boy with Down syndrome, but none of it makes her happy. In a telling detail, a photograph of Sheba in her youth, dressed in a punk style, is shown in her studio.

|

| Teenage Sheba was a Siouxsie & The Banshees fan |

Like her pottery and the art in her shed, this photograph suggests a life unfulfilled, that she imagined a bigger, more bohemian life for herself. This was the time in her life when she felt most free and most herself, before she was married or had children, and it is this sense of fulfillment she tries to reclaim by ultimately entering into a relationship with one of her students.

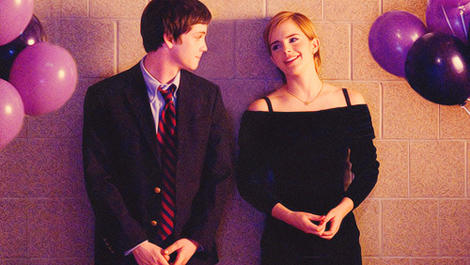

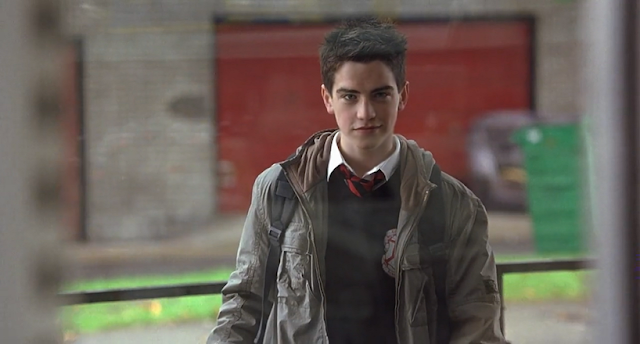

Her relationship with 15-year-old Steven Connolly is particularly disturbing because actor Andrew Simpson certainly looks this age. At first, he satisfies her idealism, and helping him develop his potential as an artist makes her feel useful in a way she hasn’t felt in a long time. She tells Barbara it was he who began to pursue her, constantly following her and playing on her sympathy with sad stories about his family life. The first time she leaves her family to meet him, lying about where she is going, the camera briefly lingers on her son and husband, showing her last minute hesitation.

In viewing the situation as one where he pursued her and she was helpless in her desire (whether or not Sheba’s story to Barbara is reliable), she allows herself to feel young, desirable and like a teenager again, experiencing clandestine affairs. In this sense, her much older husband is recast as her father, which Connolly thinks he is when he sees him. Sheba’s relationship with her daughter, who is the same age as Connolly, is also changed as they both enter a similar world of teenage dating.

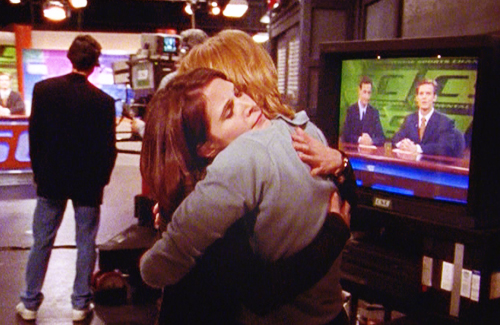

|

| Teenage Steven Connolly pursues Sheba |

In the end, it becomes clear Connolly can’t take the burden of this complicated relationship and the knowledge that she has a family and feels he has been used by her. In her efforts to reclaim her own carefree youth, she has been stealing his and forcing him to grow up. In one telling scene, Connolly looks through her records and is unfamiliar with the artists, highlighting their age gap. The wrongness of Sheba’s actions is brought home to her when Connolly, naked post-sex tries on her son’s hat. At the sight of him, she is repulsed and forces him to take it off.

Though both women struggle with loneliness and are unhappy with their lives, the different ways they deal with similar emotions cast them in degrees as predator and prey.

Alone and undervalued, Barbara rapidly develops an obsession with her younger colleague, which makes her feel more vital and connected to the world. She is fascinated with the exotic character that Sheba seems to be, someone so different from her. She is also jealous of Sheba, as in her narration she says that people like her only think they know what real loneliness is. With this in mind, when she discovers Sheba’s affair with Connolly, she uses it to blackmail her into being her friend.

Though society easily defines a woman like Sheba as a predator, and she is punished with a jail sentence at the film’s end, Barbara’s predatory nature is much subtler and hidden. She looks at Sheba’s life noting how around her family, she acts in a serving position, making dinner and tidying the dining room while the others sit and talk, that she alone has had to take care of the children. This allows Barbara to resent Sheba’s family as a burden placed on her that she’d be glad to be rid of.

Several characters mention Barbara’s old friend, Jennifer, who she doesn’t want to talk about, suggesting she has had these obsessives friendships before. They also suggest Barbara’s attraction to Sheba is actually repressed lesbian desire, unfortunately casting this desire as predatory by connecting it with Barbara’s manipulations. In one scene, the camera, showing her point of view, focuses on an extreme close-up of one of Sheba’s golden hairs falling. Like a lover, Barbara holds it delicately, as if it is precious to her and saves it in her diary.

|

| The camera shows Barbara’s point of view as she gazes at Sheba with lust |

In addition, during a moment of casual dancing during her first visit to the Harts, Barbara’s eyes scan up Sheba’s body, and her dancing is shown in slight slow motion, accentuating Barbara’s lustful gaze. This gaze challenges the societal view of an older woman as a sexless grandmother and presents her as someone with active sexual desires.

Sheba is also guilty of manipulating Barbara and dismissing her because of her age. Early on, when she first begins to confide in Barbara, she sees her as a good person to talk to because she assumes she does not have her own life or secrets. She assumes a woman like Barbara would be glad just to have a friend, and dismisses any idea that she could have sinister intentions running contrary to the older woman’s assumed place in society as the grandmother. With this assumption, she begins to prey on Barbara’s loneliness, continuing to see Connolly and buying Barbara gifts to silence her. The viewer begins to feel sympathy for Barbara here as her narration reveals that she lives in a fantasy world, believing she has a wonderful relationship with this loving friend who will take care for her in her old age.

|

| Barbara dresses as a doting grandmother to visit the Harts |

Similarly, Barbara shows her first genuine smile when she is first invited to Sheba’s family dinner. Because the film follows her through the minute details of getting ready; buying clothes and having her hair done, the invitation is inflated in importance. As the details momentarily consume the film, the preparations seem to become her whole life, revealing how small, unimportant and lonely it is. The insert shot of her in the mirror, nervously touching her hair stresses her concern about looking a certain way and fitting into the role expected of her.

She emerges wearing pearls and carrying flowers, the very picture of a sweet grandmother.

The film takes great care to show Barbara in an unflattering light, making the signs of her age, her thinning hair, neck fat and heavily wrinkled skin, appear (for lack of a better word) pathetic. It also suggests Barbara’s appearance mirrors her cold-hearted nature. This seems a bit hypocritical, as much of the film can be interpreted to suggest that the older woman should not be dismissed as having none of her own desires and secrets. By aligning the film with Barbara’s point of view and then including scenes, like the overhead shot of Barbara smoking in the bath with her sweaty older body on display, it is suggested not only that she is monstrous, but that she sees herself as monstrous.

|

| Barbara’s “monstrous” older body on display in a purposefully unflattering shot |