As a film-lover, revisiting old movies and watching obscure films from the 80’s is something that I spend far too much time doing. However, it’s usually worthwhile for the unfamiliar and familiar stories I get to connect with. So this week I decided to highlight two older films, one that you’ve probably seen but probably deserves to be re-watched and one that you’ve probably never heard of before.

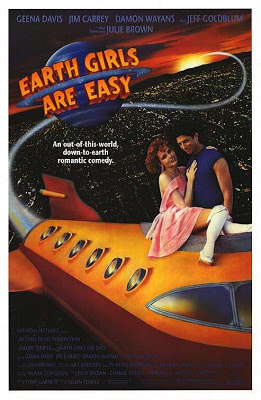

Earth Girls Are Easy

|

| Geena Davis and Jeff Goldblum in Earth Girls Are Easy |

The plot however, is pretty straightforward (click here to watch the trailer): Valerie (Geena Davis) catches her fiancé cheating on her and kicks him out and only a day later, three furry aliens, Mac (Jeff Goldblum), Zeeblo (Damon Wayans) and Wiploc (Jim Carrey), crash land in her pool. The aliens get a makeover and Mac and Geena fall in love, high-jinks and a few musical numbers ensue, and Valerie cuts her ex-boyfriend out of her life and goes for the good guy, Mac.

Everyone in the film is ridiculous, with over-blown stereotypes representing both men and women. For the most part, the film is just what it appears to be, lighthearted camp; however, there are some moments of more subtle commentary, particularly in the two musical numbers. Both of the film’s songs mock superficial standards of beauty as well as the mentality surrounding much of the beauty industry with lyrics such as, “You’re cute and fresh and wholesome/but science has a cure/the natural look is nowhere” from the song “Brand New Girl.”

Other songs are critical of reductive behavior, such as the infantalization of women with one of my favorite lines in the whole movie, “I talk like a baby/ And I never pay for drinks” in “I Am A Blond.” The glorification of women who act like children has long been problematic, and I appreciate Brown’s awareness of it and her parody of its consistent presence. And while much of the plot centers around the sexual objectification of women (the reason the aliens crash land in Valerie’s pool is because they spotted her sunbathing from space) it’s done in an over-the-top, satirical fashion with a lot of tongue-in-cheek breast-jiggling and intentional flashing of Davis’s thigh.

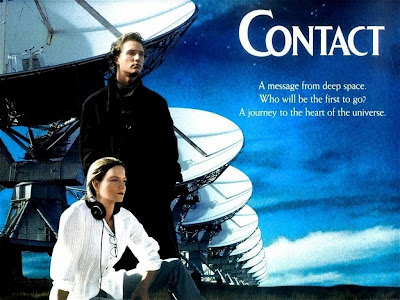

Contact

|

| Jodie Foster and Matthew McConaughey in Contact |

In case you don’t remember the plot, here’s a little review: Ellie (Jodie Foster) is a young, brilliant SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) astronomer who listens for extraterrestrial life in New Mexico and, of course, finds it one day. Subsequently, plans for a transportation device are discovered encoded into the radio transmission sent by the aliens, and this unleashes a storm of media, government fear, distrust and discussions about god. Ellie wants nothing more than to be the person strapped into the transporter, but she has to battle bureaucracy and sexism to get there. Despite how it sounds, one of the things that I love about this movie is that aliens actually play a very small role in the film; mostly this film is about humanity in times of crisis.

One of the reasons that I think this movie is great for feminists, though, is that Jodie Foster is intelligent and driven. The focus of the movie is not on how she looks (ninety percent of the movie has her in jeans and a t-shirt with a messy ponytail) but rather on her intense search for truth and scientific discovery. Her excitement for her career and the passion with which she pursues it is admirable, as is her bravery. In fact, Ellie’s character explicitly points out that it is not faith that drives her to attempt the transportation machine of the aliens but rather a sense of adventure (a characteristic we should be actively cultivating in young women today). While there is a side-plot of a relationship with Matthew McConaughey, it’s never the core of the film; the crux of the movie is the point where she encounters and believes in something greater than herself.

|

| Jodie Foster as Dr. Ellie Arraway in Contact |

The film also passes the Bechdel Test in that two women, with names, talk to each other about something other than a man for more than thirty seconds. While the majority of the characters are still male, which is understandable in some facets since most of politics and science are still dominated by men, the main staffer at the White House is a woman, and she too plays a strong role in the development of the plot.

For me, the greatest point of this movie is how it shows a female protagonist dedicated to scientific discovery and the fulfillment of her dreams. Often when women are portrayed as ambitious and career-oriented, they are simultaneously shown as cold, evil, and downright heartless (think Meryl Streep in The Devil Wears Prada). In Contact, however, Foster is genuine and polite to the people around her, much like successful women really are.

In fact, in preparation for the film, Jodie Foster met with Dr. Jill Tartar, one of the senior SETI scientists, to discuss her life in the sciences, sexism and what SETI researchers really do. One of the best aspects of this movie is the portrayal of sexism in Ellie’s career without ever really addressing it, just showing how commonplace it is and how gracious she is in dealing with it (again, a far cry from the usual ice-queen portrayal of a successful woman).

The movie also offers a discussion of science versus religion and whether the two can coexist, or how much their goals might even have in common; I think it’s a great addition to the film, in that it is a constant ongoing discussion in our society and would surely be discussed in the event of aliens. Though even without the aliens, the parallels to our own current national debates on same-sex marriage, revolving between the door of religion and science, is provocative. In this way, unlike so many science-fiction films, there is a strong sense of cultural context and philosophical consideration, which pulls the film away from action-based plot lines and into a far more relevant space in drama.