Written by Megan Kearns. | Spoilers ahead.

[Trigger Warning: Discussion of rape and intimate partner violence]

Is Gone Girl a misandry fest, a subversive feminist masterpiece, or a misogynistic mess? All of the above?

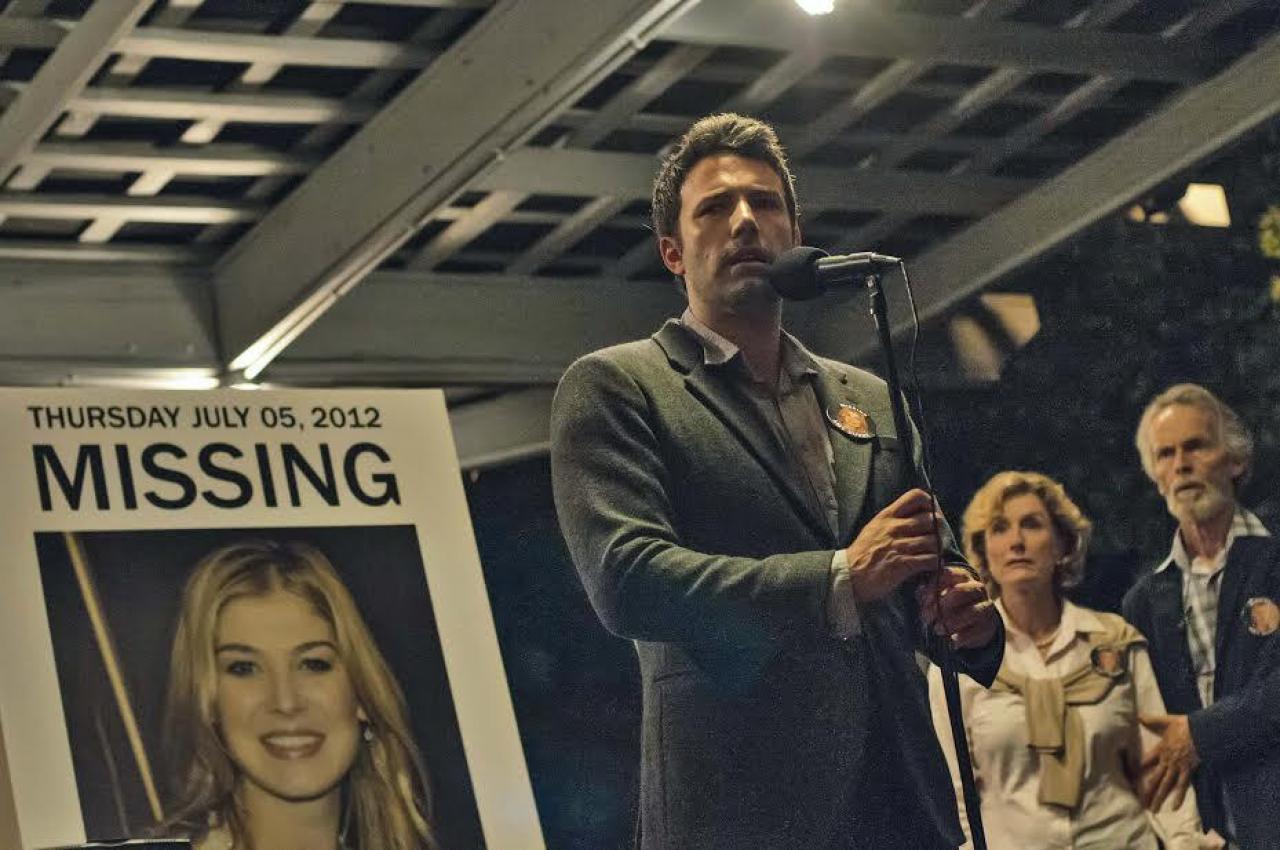

I loved Gone Girl. It intrigued me with its labyrinthine plot, complex characters and noir motif. It simultaneously enthralled and enraged me. There is so much to unpack regarding gender. While a whodunit mystery revolving around the disappearance of Amy Dunne (Rosamund Pike), and whether or not her husband Nick (Ben Affleck) is the culprit, the crux of the film is the dissolution and destructive unraveling of a marriage. It begs the question: Do you ever really know the person you marry?

Deftly written by Gillian Flynn (who wrote the novel as well) and expertly directed by David Fincher, it’s an uncomfortable film that boldly examines the underbelly of love and marriage and how the media shapes perception. Told from the perspectives of both Amy (often through her diary) and Nick, Gone Girl cracks wide open and shines a spotlight on the often gendered expectations within a heteronormative marriage. Society pressures women to be flawless, never wavering in an aura of perfection. Gone Girl takes a sledge hammer to that.

In an outstanding and riveting performance by Rosamund Pike, Amy is a fascinating character. She’s brilliant, pragmatic and narcissistic. We watch her shift effortlessly from a devoted and then fearful wife to a calculating and fearlessly manipulative villain. A ruthless, Machiavellian anti-hero, Amy morphs into whatever persona she needs to don to obtain her objective. She wears personalities like a cloak, shrouding her true nature and intentions. Filled with rage, she discards the role of the docile wife. She’s not going to live on her husband’s or any man’s terms. She refuses to fulfill society’s expectations.

Amy uses her femininity to achieve her diabolical goals. She uses her sexuality, wielding it as a weapon. They are tools in her arsenal to ensnare and punish men. But just as she readily adopts stereotypical feminine traits when she needs them, she also utilizes stereotypical masculine traits of anger and violence. Her gender informs her actions and the way she perceives the world. However, Amy despises gender norms and doesn’t want to be constrained by them. She doesn’t want to be a satellite to a man. She wants to do whatever she pleases, regardless of the consequences.

We don’t get to see women as anti-heroes or villains nearly enough. As it is, we suffer a dearth of female protagonists in film. While an abundance of female anti-heroes in film reigned during the 1930s, we suffer a lack of female anti-heroes in film today. We do see more female anti-heroes on television: Patty Hewes (Damages), Olivia Pope (Scandal), Gemma Teller Morrow (Sons of Anarchy), Skyler White (Breaking Bad), Carrie Mathison (Homeland), Elizabeth Jennings (The Americans) and Claire Underwood (House of Cards). But we still see far more men in anti-hero roles on television.

Now, I don’t believe that female protagonists need to be “likable.” There’s a compelling argument by Roxane Gay as to why they shouldn’t be likable. Conventionally unlikable women don’t give a shit about what others think of them. And neither does Amy. That’s what makes Gone Girl somewhat refreshing. Here we see an unapologetically ruthless woman.

I have to applaud Amy’s rage and defiance. Although I’m horrified by her disturbing, sociopathic and misogynist tactics. This is why I relish Amy’s notorious “Cool Girl” speech. “The cool girl. The cool girl is hot. Cool girl doesn’t get angry. … And she presents her mouth for fucking.” This is a scathing commentary on how men see women as objects, as vessels, as accessories, not as entities unto themselves. I couldn’t help but say, “FUCK YEAH,” while Amy recited it. Her speech succinctly encapsulates the Male Gaze and hetero men’s expectations of women, while shattering the illusion that women are never angry and that women merely orbit men, suffocating their own needs and desires. Amy’s speech illustrates that society tells women to contort themselves to seek men’s approval.

As much as I cheer for the astute and searing commentary in the “Cool Girl” speech, Amy also condemns women complicit in this charade. She despises how women fall into their prescribed roles, all for the enjoyment of men. When Amy recites this speech, she’s driving in a car, gazing at myriad women passing by. As David Haglund points out, director David Fincher chose the images, not of men but of women, to coincide with Amy’s words. So while the words condemn men, the corresponding images implicate women, making everyone culpable. It becomes a condemnation of women themselves, that they shouldn’t fall into the trap of pantomiming this performance.

What could have potentially been a feminist manifesto mutates into something ripped out of a misogynist’s or Men’s Rights Activist (MRA)’s warped fantasy.

The biggest problem with Gone Girl lies in the tactics Amy utilizes to punish men — by faking intimate partner violence and rape. Amy ties her wrists with rope, squeezing and tightening them while turning her wrists and she hits her face with a hammer to simulate abuse. She repeatedly shoves a wine bottle up her vagina to simulate the bruising and tearing from rape. Amy falsely accuses men of rape, stalking and abuse, all for her own ends. Amy convincingly plays the role of an abuse survivor. It’s scary because this is the kind of bullshit people believe — that women lie and make shit up to wreak vengeance on men.

Author/screenwriter Gillian Flynn said that Amy “knows all the tropes” and she can “play any role that she wants.” But therein lies the problem. Abuse victims and survivors are not merely “tropes” or “roles.” Amy pretends she is being abused in order to frame Nick by writing in her diary that she fears for her life and worries that her husband might kill her. She says she feels “disposable,” something that could be “jettisoned.” Women murdered at the hands of abusive partners are typically treated as disposable in our society. People tell victims/survivors that they should have known better, they must have provoked their abuse. People question why victims/survivors stay with abusive partners. People put the onus on women to prevent rape. These are the myths that films, TV series and news media reinforce. It’s extremely problematic to equate Amy playing “the role” of an abused rape victim with actual women abused and raped.

As a domestic violence survivor, I find the turn the film takes extremely offensive. This is the narrative too many people already have embedded in their minds — that women exaggerate, fabricate and lie about abuse and rape in order to trick or trap men in their web of lies. This is one of the biggest, most pervasive and most dangerous myths about abuse. Here’s the reality. One in four women in the U.S. report intimate partner violence. One in three women worldwide will experience partner abuse. One in five women report being raped. Yet here is this film (and book) contrasting reality and reifying rape culture.

We also see victim-blaming underscored in the film from Amy’s neighbor Greta. When they first meet, Greta comments on the bruise on Amy’s face saying, “Well, we have the same taste in men.” Yet when the two women are watching a news program on Amy’s disappearance and how the leading cause of death for pregnant women is homicide (it is), Greta calls on-screen Amy (feigning ignorance that the real Amy is right next to her) a “spoiled,” “rich bitch.” She goes on to say, “While she doesn’t deserve it, there are consequences.” While this is a commentary on privilege and Greta has survived abuse too, this also amounts to victim-blaming 101.

But the victim-blaming doesn’t stop there. One of Amy’s exes talks to Nick and tells him how she falsely accused him of rape and had a restraining order placed on him. He tells Nick that when he saw her on the news missing, “I thought there’s Amy. She’s gone from being raped to being murdered.” Again this underscores the myth that women lie about rape and abuse. But the numbers are so low for reports of false rape and domestic violence that they are almost non-existent.

Victim-blaming myths permeate every facet of our society. Janay Rice’s abuse and the resulting #WhyIStayed conversation recently highlighted the myriad myths people believe about intimate partner violence, particularly when it comes to women of color. People feel they need “proof” to verify or corroborate a victim/survivor’s trauma. Society perpetually places the onus on women for their abuse rather than on where it belongs: with the abuser. As we’ve seen with Marissa Alexander, the legal system doesn’t reward but rather punishes domestic violence survivors. This happens again and again, over and over. Women are not believed. And it’s dangerous to keep feeding this narrative.

Rape is “an epidemic.” Violence against women is an epidemic. We live in a rape culture that inculcates the abuse and objectification of women and dismisses violence against women. Society makes every excuse for abusers while it unilaterally shames and blames victims and survivors of intimate partner violence, rape and sexual assault.

Some might try to assuage Gone Girl’s misogyny by declaring Amy’s misandry or by underscoring that there are two female characters – Detective Rhonda Boney and Margo Dunne – who are onto Amy’s game. But it doesn’t. When you have a protagonist doing despicable things, the film/TV series often straddles a fine line between condemnation and glorification. However, there is a way for a film/TV series to delineate their message: by the comments and perspectives of ancillary characters. Breaking Bad illustrates this beautifully. Despite what many fanboys got wrong, we are NOT supposed to identify with power-hungry, abusive, rapist Walter White. We may be fascinated by Walter’s fierce intelligence. But we are supposed to identify with Jesse and Skyler, both of whom are the heart and conscience of the show. They are the ones telling us the audience, both overtly and covertly, that Walter’s actions are despicable and monstrous.

In Gone Girl, almost every character condemns and despises Amy. They loathe her for her manipulations and how she has framed Nick. But no character comments on how Amy’s actions reinforce rape culture. Not one. Rhonda could have easily mentioned the stats for women reporting rape or domestic abuse, how few rape and abuse cases are brought to trial and even fewer convicted because of victim-blaming biases. Nick’s sister Margo could have said how horrible Amy’s schemes are not only for her brother but the implications for other women too. But everyone in the film only focuses on how Amy’s actions impact Nick. Nick even says at one point in the film, “I’m so sick of being picked apart by women.” (Boo hoo, poor Nick. Isn’t that every misogynist’s anthem??) So when Nick slams Amy’s head into the wall and calls her a “cunt” towards the end of the film — despite his abusive actions and misogynist language — we the audience are supposed to sympathize with him because he just wants to be a good dad, because he’s the one victimized by this manipulative shrew.

I wish I could love this film without reservations. I wish I could say that Gone Girl is a subversive feminist film exposing myriad gender biases and generating a much-needed dialogue on rape and domestic violence. Yet it reinforces dangerous myths rather than shattering them. The embedded “Cool Girl” speech rails against the patriarchal notion that women serve as nothing more than accessories and sexual objects to men. But the film falters by playing into a victim-blaming narrative reinforcing rape culture.

We need more complex female protagonists. We need more female anti-heroes and villains. If only we could have one in a film that doesn’t simultaneously perpetuate the misogynist notion that women lie about rape and abuse.

Megan Kearns is Bitch Flicks’ Social Media Director, a freelance writer and a feminist vegan blogger. She’s a member of the Boston Online Film Critics Association (BOFCA). She tweets at @OpinionessWorld.