|

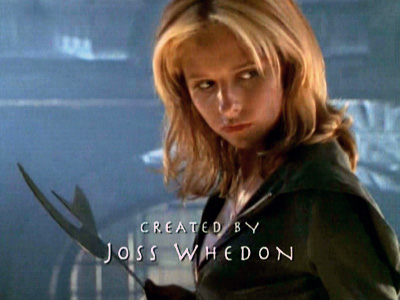

| Buffy Summers (Sarah Michelle Gellar) in Buffy the Vampire Slayer |

Guest post written by Jennifer M. Santos.

“It’s a relief to hear papers that don’t go on about feminism.” Such was

Patricia Pender’s report on the mood of attendees at the second

Slayage Conference in 2006, just three years after Buffy ended (5). Pender punctuated her discussions of an atmosphere rife with concerns of contextual redundancy with the exclamatory parenthetical, “not more feminism!” (5). Nonetheless, the prevailing mood of 2006 did little to halt the “Is Buffy feminist debates?” during the following year: in 2007, C. Albert Bardi and Sherry Hamby claim that Buffy “revel[s] in her phallic power (yes, phallic –don’t forget the omnipresent stake)” while Misty Hook returns to Joss Whedon’s self-proclaimed “radical feminist” roots (107, 119).

Which perspective reigns in 2012? Which should? Neither. Or both. More precisely, Pender’s 2002 piece – now a decade old – got it right when suggesting that Buffy’s “ambivalent gender dynamics”makes it a “site of intense cultural negotiation” (35, 43). When considered from the perspective of the Gothic tradition from which the earliest English-language vampire first sprang, ready for mischief, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Buffy defies easy categorization. Instead, the show invites viewers, along with its characters, to negotiate – rather than “simply” navigate – cultural gender norms.

The Gothic has long been known for its tendency to transgress boundaries, especially those boundaries associated with gender. So much so, in fact, that an industry of gendered Gothic scholarship has grown from Ellen Moers’ first invocation of the term “female Gothic,” used initially to refer to Gothic novels authored by women (and which typically function as “birth myths”) to Anne Williams’ more inclusive, dynamic formulation wherein female Gothic “does not simply break the rules, it creates a new game with different rules altogether” (172). Buffy not only creates a new game; it suggests a new field of play for the game by transgressing – and then effacing – traditional gender boundaries.

In 2012 – an era of the female as victim (as seen in the

Twilight series and even to some extent in the Sookie Stackhouse novels) or “more masculine than the men” (perhaps a holdover from the Lara Croft or Xena) in Gothic and in larger popular culture – the available spaces for female representation are typically depicted as domestic entrapment or usurper of patriarchy (a role distinct, it should be noted, from that of matriarch). From the pilot episode to the conclusion, Buffy enters and redefines each space. She may be, as Hannah Tucker describes, a “Wonderbra’d blond chick fighting vampires” meant to invert the convention of “the blonde girl who goes into a dark alley and gets killed”

as Joss Whedon has described his vision of the show, who elides the domestic sphere (quoted in Byers185, Belle). She may also be the means of celebrating what Whedon has called “

the joy of female power: having it, using it, sharing it” in the final episode of Buffy – where any female who could receive slayer powers does receive slayer powers (quoted in Gottlieb). She may elide the domestics pace in each of these examples.

But for all her “on field” triumphs in revising the game, her exodus from domesticity is not “complete.” Nor need it be. In fact, Buffy continually cycles in and out of domesticity, as her mother pressures her to lead a normal life even as her Watcher prods her towards her destiny, and as she sets out for college on her own only to return to the home a year later to care for her ailing mother and, later, her sister. [1] And, notwithstanding the celebratory conclusion of the series, Angel episode “The Girl in Question” situates Buffy in a new domestic space in Rome with the Immortal. These series-wide arcs indicate that the either/or dichotomy no longer reigns as such; Whedon neither wishes to simply “expos[e] perils” (although

Frances Early convincingly argues that Buffy does just that) nor create “a dark mirror reflecting patriarchy’s nightmare” (Williams 107).[2] Instead,the series as a whole unpacks, overturns, and undercuts – in other words, it transgresses – traditional understandings of not only female/male, but also of feminism itself.

|

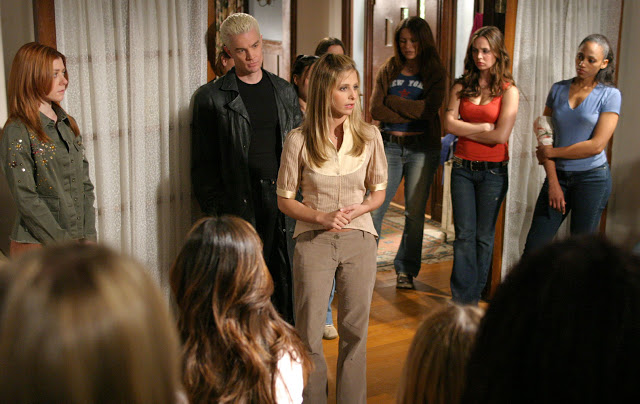

| Buffy in the series finale |

The final episode – “Chosen” – is case-in-point.When Buffy shares her power with all women, vanquishes the First Evil, destroys the Hellmouth, and leaves a literally decimated Sunnydale behind to start a new life, the oppressive, exclusionary, and controlling “signs of the father” are defeated.[4] Buffy,with Willow’s assistance, imbues all would-be-slayers with mystical strength,actualizing power in all women with the potential to receive it. We may further rejoice in the revelation that a mysterious emissary of female Guardians not only predates man but also contributes to Buffy’s quest in providing a pivotal tool that enables empowerment. But its representational power is complex, and has led a number of viewers – academic and nonacademic alike, in my experience – to probe their own subjectivities.

One argument goes something like this: given these overtly feminist messages, the troubling intrusion of masculine power structures complicates a “happy ending.” Recall the scythe that enables sharing of female power. The visual representation of this tool might well be considered symbolic of the phallus. To be effective in empowering women, Willow must join with the scythe in a scene rife with sexual imagery, from Willow’s initial resistance and nervousness to her gasp of awe (“oh my goddess”) to her physical collapse that implies post-coital bliss. Of course, female pleasure here is not sublimated to the male, unless one considers that act as coerced for the greater good, much as Victorian mothers told their daughters to”Lie still and think of England” on their wedding nights.[5] Her virgin-like nervousness before the act –and her statement that such an act will take her beyond anywhere she’s been before – also speaks to a sublimated sense of self for duty in encountering the phallus (“Chosen”). Here, an engaged viewer might ask (and have asked), “can this support a feminist message?”

Indeed, the implications of this act are all the more poignant when one considers that Willow is a lesbian in a committed relationship. That the phallus was thrust upon this woman by other, albeit well-meaning, women speaks to the deep-rooted patriarchal use of women by culture, similarly attested to by the Watchers’ Trials where Buffy is placed in a dilapidated house, stripped of powers that were initially forced upon her predecessors, and exposed to mortal danger – all “in the name of the father.” Yet it is Giles, the father-figure, who breaks from tradition and assists Buffy in this trial, thus indicating a deeply complex and ambivalent perspective on the cultural positioning of women.

Around dinner tables and over cups of coffee, nearly a decade after the series concluded, I’ve witnessed this discussion unfold time and again. And, I think this is the key interpretative moment: are women, the series asks, dependent on men to create a new field of play? Or might the show call into question the norms and expectations of both genders? The answer to these queries may well be found in Spike’s role in the series’ finale. Certainly a number of conversations turn to Spike’s role. In its layers of ambivalence that call upon men to not only transgress but efface normative boundaries, it points to the latter.

As Wilcox notes, Spike only glows with his own power after power has been distributed to women; it is, ultimately, the eternal man, in the form of the undead Spike, whose heroics save the day (104). Indeed, while Spike assumes his heroic pose, Buffy and her cohort of potentials-turned-slayers operate as helpmeets, distracting the minions of evil until the male sacrifice – reminiscent of the Christ promoted by patriarchal religious structures – can deliver the women from a dark destruction. This comparison gains credence from the fact that this unlikely hero, after the destruction of his vampire form, is again resurrected in Angel,revealing a reification of a patriarchal structure: the female can only be empowered – can only share her power – at the behest of a man. This ambivalent twist on a seemingly-feminist agenda asserts itself further in “Chosen” when the phallically-named Spike shoots beams of light across the female expanse, with one slicing upwards and directly into the room of the lesbian witch who embraced the phallus to empower others.[6] This final act seems to reclaim phallic power through intrusion.

|

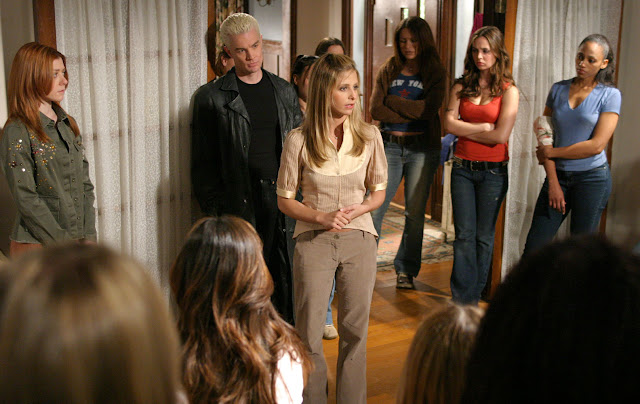

| Buffy and Spike |

Seemingly,then, the series remains locked in the outmoded feminist argument, regardless of the subjectivities it invites viewers to explore, that describes a binary power struggle that becomes even more insidious when we consider that Spike refers to Buffy in his final words as “lamb,” implying that Buffy herself must sacrifice power to empower others. Further consideration of this thought is disturbing, as it implicates Buffy herself in the totalizing power of a patriarchal system (as the “one girl in all the world” who is chosen), as does the elitist selectivity of the chosen few who receive the newly redistributed power. These plotpoints beg the question of whether collective female empowerment can exist within current structures.

The answer to this query, it seems, lays in the very ambivalence that the show’s conventions hint at across the seven-seasons. These various genderings indicate that it is only in comfortable ambivalence that true empowerment can be achieved for all members of society. Perhaps it is our own discomfort with this ambiguity that compels us to return to the either/or feminist debate surrounding Buffy again and again, in print and in casual conversation. Yet, in fact, it is the liminal– the space in-between – that is brought to the foreground, through the characters of Spike and Buffy. As a vampire, Spike exists on the borders, oscillating between life and death,between human and demon and between good and evil (even without a soul, Spike often acts for the greater good).[7] It is his liminality that makes his identification with the phallus so intriguing: his story is that of a sensitive, somewhat effeminate, human male lacking self-confidence in life thatis gained in unlife. This newly-found confidence sends him on a quest for power as conceived of by cultural norms:his self-assertion takes a violent turn during which he quite literally eliminates the “other,” and, during this time, trades his given name, the ubiquitous William, for his phallically-charged nickname. That he follows the traditional conquest path to “glory” makes his shift to champion of the people all the more interesting: he moves from the effeminate male (the “momma’s boy”) to the”masculine” male, experiencing both worlds before consciously choosing to “be a better man,” as Buffy puts it, a task that for Spike involves embracing both the male and female cultural norms (“Never Leave Me”).[8] It is not insignificant that it is Spike who sacrifices himself – often the female role (excepting, for a moment, the Christ comparison) – to save the world. By adapting cultural gender norms for new purposes, Spike offers a form of feminism that might be characterized, stripped of jargon, as “human” feminism.

Similarly, Buffy herself operates as a liminal figure, oscillating between her home life and her sworn duties, the human part of her and the demon part of her. She relies on what may be seen as a patriarchal form of power: violence and control. She further maintains the traditionally-male isolationist stoicism while attempting to reconcile her place in the world with cultural norms, yet only when she becomes comfortable having – and not having – power is she able to empower others. This is the crux of the issue: only by blurring binary distinctions that constrain men and women can the rules change within the system. The staples of oppressive conventions have not been overturned: the system remains in place:globalization of female power, then, does not simply cross boundaries or”turn around” as revolution may imply in this context.[9] It instead offers the hope that if one cannot rend asunder what William Blake would call “mind forged manacles” of cultural norms, then it can infuse them with elasticity. And in 2012, when male and female icons alike so often return to the repressed as with Gothic of yore, the role Buffy can play in renegotiating a space for feminism from beyond the grave is worthy of continued attention.

Jennifer M. Santos has taken a break from professoring to do more writing about fun, feisty females. When she’s not writing about Buffy or Lady Gaga, she’s using her Ph.D. in English to unearth nineteenth century vampires. And when when’s not doing that, she continues the never-ending battle to convince her cats that she’s the alpha.

Works Cited

Angel: Season Five on DVD. Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment,2005.

Bardi, C. Albert and Sherry Hamby. “Existentialism Meets Feminism in Buffy the Vampire Slayer.” The Psychology of Joss Whedon: An Unauthorized Exploration of Buffy, Angel, and Firefly. Ed. Joy Davidson. Psychology of Popular Culture Ser. Dallas: BenBella, 2007. 105-117.

Buffy the Vampire Slayer: The Chosen Collection. 144 episodes. DVD. Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment, 2006.

Byers, Michele. “Buffy the Vampire Slayer: The Next Generation of Television.” Catching a Wave: Reclaiming Feminism for the 21st Century. Eds. Rory Cooke Dicker and Alison Piepmeier. Hanover, MA: Northeastern UP, 2003. 171-187.

Chandler, Holly. “Slaying the Patriarchy:Transfusions of the Vampire Metaphor in Buffy the Vampire Slayer.” Slayage: The Online International Journal of Buffy Studies. 3.1 (Aug. 2003): 62pars. 17 Jan. 2006 <

http://slayageonline.com/PDF/chandler.pdf>.

DeLamotte, Eugenia C. Perils of the Night: A Feminist Study of Nineteenth-Century Gothic. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1990.

Early, Frances. “Staking Her Claim: Buffy the Vampire Slayer as Transgressive Woman Warrior.” Slayage: The Online International Journal of Buffy Studies. 2.2 (Sept.2002): 30 pars. 17 Jan. 2006 <

http://slayageonline.com/PDF/early.pdf>.

Hook, Misty K. “Dealing with the F-Word: Joss Whedon and Radical Feminism.” The Psychology of Joss Whedon: An Unauthorized Exploration of Buffy, Angel, and Firefly. Eds. Joy Davidson and Leah Wilson. Psychology of Popular Culture Ser. Dallas: BenBella, 2007. 119-129.

Jowett, Lorna. “The Summers House as Domestic space in Buffy the Vampire Slayer.” Slayage: The Online International Journal of Buffy Studies. 5.2 (Sept.2005): 40 pars. 17 Jan. 2006 <

http://slayageonline.com/PDF/jowett2.pdf>.

Pender,Patricia. “‘I’m Buffy and You’re…History:’ The Postmodern Politics of Buffy.” Fighting the Forces: What’s at Stake in Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Eds. Rhonda V. Wilcox and David Lavery. Lanham, MD:Rowman, 2002. 35-44.

—. “‘Where Do We Go From Here?’: Buffy Studies and Slayage 2006.” Slayage: The Online International Journal of Buffy Studies. 6.1 (Fall2006): 24 pars. 9 Aug. 2012 <

http://slayageonline.com/PDF/Pender.pdf>.

Wilcox, Rhonda V. Why Buffy Matters: The Art of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2005.

Williams, Anne. Art of Darkness: A Poetics of Gothic. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1995.

Williamson,Milly. “The Predicament of the Vampire and the Slayer: Gothic Melodrama in Modern America.” The Lure of the Vampire: Gender, Fiction and Fandom from Bram Stoker to Buffy. London:Wallflower, 2005.

Vint, Sherryl, “‘Killing Us Softly’? A Feminist Search for the ‘Real’ Buffy.” Slayage: The Online International Journal of Buffy Studies. 2.1 (May 2002): 26 pars. 17 Jan. 2006 <

http://slayageonline.com/PDF/vint.pdf>.

Notes

[1] Jowett’s “The Summers House as Domestic Space in Buffy the Vampire Slayer” provides an excellent account of the Summers’ house as a site of domesticity both with and without the presence of Buffy’s mother. Her analysis, coupled with Eugenia C. DeLamotte’s observation that Gothic heroines perpetuate a cyclical enclosure by venturing out of the home simply to return to it again, reinforces the problematic nature of Buffy’s own empowerment. That is not to say that a woman cannot be a stay-at-home feminist if she chooses the home for herself, but rather to develop the sense of cyclical entrapment that Buffy experiences for seven years.

[2] In her discussion of Buffy as a “narrative of disorderly rebellious female as well as an effective experiment in…’open images,'”Early asserts that Buffy “expose[s]stereotypes and coded symbols that shore up a rigid war-influenced gender system” (3, 29). Further, Holly Chandler asserts that “Buffy confidently yanks the ugly face of the patriarchy out into the light of day, where, she hopes, it will be burnt to a crisp”(62). Both Early and Chandler author valuable arguments portray Buffy as subversive from a woman’s studies standpoint, and I build on their observations in probing the nature of subversion as applicable to both men and women.

[3] Whedon has articulated his desire to “make teenage boys comfortable with a girl who takes charge of the situation” (quoted in Vint 13).

[4] For additional “signs of the father” in Season 7, witness Giles’ attempted murder of Spike, the villain’s adoption of the patriarchal garb of religion, and even the villain’s assumption of a female form named Eve.

[5] A corollary problem to note is that the female creators of the scythe choose to bury it deep within mother Earth, violating,on a broad level, the natural world. Although one may explain this violation as a justified critique of a world that denigrates women and enslaves them to fight monsters or even as what Williams calls a “metaphor for accomplishment, a mode of self-creation,”the ultimate use of the scythe further complicates the issue (158).

[6] Rhonda Wilcox makes a similar observation, discussing Spike and Willow in relation to subconscious and conscious in Why Buffy Matters (104). Wilcox also provides further evidence for those who may question Spike’s phallic associations: in “Tabula Rasa,” wherein the characters experience an amnesia spell, Spike discovers the name “Randy” sewn into his jacket and assumes it for his name,complaining, “‘Why didn’t you just call me Horny Giles or Desperate For A Shag Giles?’ Given the fact that the episode after ‘Tabula Rasa’ is ‘Smashed’ (6.9), in which Buffy and Spike first have sex, the names seems more than appropriate. One might argue that the name Randy reiterates the sexual implications of the name Spike” (60).

[7] In fact, it is worth mentioning that the soulless Spike undertakes his own journey and trials to retrieve his soul, while the only other ensouled vampire in the Buffyverse, Angel, is cursed with a soul as a punishment.

[8] Milly Williamson notes that, “[l]ike the pre-twentieth-century Gothic, the appeal of today’s ‘new’ vampire tale is to do with its ability to represent what is disavowed, to speak to anxieties and desires that are difficult to name” (69). That the anxieties of gender remain ambiguous further connects Buffy to the Gothic tradition.

[9] Williams returns to the etymology of”revolution” and reminds us that “the word means to ‘turnaround'” as well as to “cross forbidden boundaries” (172).