|

| Martha Marcy May Marlene (2011) |

|

The radical notion that women like good movies

|

| Martha Marcy May Marlene (2011) |

|

|

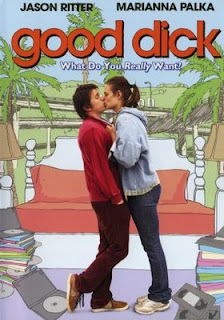

| Good Dick (2008) |

For the lead male role I wanted to see the lover archetype illustrated in a way that is all loving, all kind, all ways. I knew the guy had to be strong and thereby protective, but not in a stereotypical sense. Definitions of masculinity often tend to be deformed in our culture, forgetting the good fight and glorifying what I like to call, “The cardboard cutout man.” In Good Dick the man’s power has nothing to do with his physical strength, his appearance or his social status. He is masculine in a way that is genuine; this masculinity stems from his lack of chauvinism. His chivalry is his depth of kindness.

|

| Shirley Henderson, Zoe Kazan, and Michelle Williams star in Meek’s Cutoff |

Mahohla Dargis has called the film “unabashedly political,” and J. Hoberman of The Village Voice, writes

Having split off from a larger wagon train, the party elected to follow Stephen Meek (Bruce Greenwood), an extravagantly hirsute, self-regardingly loquacious guide who, in his most obvious misjudgment, brings them not to the foothills of the Cascade Mountains but the shores of a great saline lake. Is he “ignorant or just plain evil?” the Williams character asks her husband (Will Patton). “We can’t know. . . . We made our decision,” he tells her. “I don’t blame him for not knowing—I blame him for saying he did,” she replies, establishing herself as the party’s moral compass.

In a NYT piece, “Oregon Frontier, from Under a Bonnet,” Nicolas Rapold writes

“There was a quote I remembered that I had liked when I was 18 or something, that popped into my head: ‘I’ll go where my own nature would be leading,’ ” Ms. Williams said of her character, Emily Tetherow. The verse, by Emily Brontë, which continues, “It vexes me to choose another guide,” proves peculiarly apt for Mrs. Tetherow, who emerges as Meek’s prime skeptic and becomes an unusually vocal opponent. The actual diaries of women migrating West were also a source of inspiration for Ms. Williams. She said she marveled at the effort spent on writing at “the end of the longest day you could imagine.”

The forbearance and point of view in the journals comes out in Ms. Reichardt’s shading of events through the women’s perspective. Besides the constant visual metaphor of the obscuring bonnets, there are the intervening moments devoted to their chores (laundry, grinding coffee) and wide shots from their point of view that suggest their exclusion from major decision making, like when Meek and the men consult upon arriving at a lake that proves unpotable. But it’s also Mrs. Tetherow who first spies an Indian (Rod Rondeaux) who becomes another competing voice of authority as they drift along in increasing distress and disagreement.

Watch the official preview:

At home (and away) with Agnes Varda from BFI

The Day the Movies Died from GQ

Why are films so sexist? from Ad Fontes

Hall Pass: I apologize to my mother for the review I’m about to write from Slate

The ‘Blue Valentine’ Conundrum: Why So Many Boring Women In Indie Film? from The Atlantic

James Cameron the Feminist? from AMC Blog

Young Rapping Girls Call Out Lil Wayne for Misogyny from Jezebel

Insulting Chuck Lorre, Not Abuse, Gets Sheen Sidelined from The New York Times

“30 Rock” takes on feminist hypocrisy–and its own from Salon

In Which We Have to Consider Why Shorty Always Wanna Be a Thug from This Recording

The Women of ‘!W.A.R.’ from The New York Times

Not another terrorised film female from The Guardian UK

Women in Film: Where have all the strong women gone? from The Vancouver Sun

Oscar winner Geena Davis hits out at Hollywood’s female stereotypes at UN Women gala from The Herald Sun

Women breaking glass ceiling in Malayalam film industry from Sify News

No Country For Old Men Presented by The Girls on Film from YouTube

Ladies Wear the Blue (1974) from Fyddeye

In addition to promoting new filmmakers, this category is exciting because it often introduces films many of us haven’t seen, or haven’t heard much about, including Tanya Hamilton’s Night Catches Us and Dunham’s Tiny Furniture.

Best Female Lead: Natalie Portman for Black Swan

The winner here is no surprise; Portman swept the awards for her portrayal of determined ballerina Nina, which, regardless of how you feel about the film, was an amazing performance. The other nominees were Annette Bening, Greta Gerwig, Nicole Kidman, Jennifer Lawrence, and Michelle Williams.

Best Supporting Female: Dale Dickey for Winter’s Bone

This is another exciting Spirit category, as was the corresponding Oscar category (for different reasons), though there was no overlap between nominees. Other nominees were Ashely Bell for The Last Exorcism, Allison Janney for Life During Wartime

, Daphne Rubin-Vega for Jack Goes Boating, and Naomi Watts for Mother and Child

.

While the Spirit Award nominees represent a slightly more progressive and inclusive range of stories and people who tell them, they also reveal a continuing problem: the lack of films about, centering on, made by, or starring people of color. As far as I can tell (as I haven’t seen all the films, nor do I know each storyline), Hamilton’s Night Catches Us is the only nominee focusing on the experience of people of color, specifically Black Americans.

The Spirit Awards may be better than the Oscars, but we still have a long way to go.

In 2010, for the first time in history, a woman won the Oscar for best director. Directing is the most visible leadership position in film yet, in 82 years, only 4 women have been nominated for best director, and only a single woman has won. In 2009, in the 250 top-grossing domestic films, women made up only 7% of directors, 8% of writers, and 17% of executive producers. 98% of these films had no female cinematographers. And, in front of the camera, as of 2007, women had less than 30% of the speaking roles.

In addition to feature films, documentaries, and short films, there will be events such as “A Hollywood Conversation with actress Greta Gerwig” and a panel on “The Bechdel Test – Where Are the Women Onscreen?” among others.

Here are previews of some of the films we’re planning to see. You can purchase tickets for individual films or a pass for the entire weekend. If you’re in the area, you won’t want to miss this festival!

Chisholm ’72: Unbought & Unbiased

Synopsis from the official site:

Unbought & Unbossed is the first historical documentary on Brooklyn Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm and her campaign to become the Democratic Party’s presidential nominee in 1972. Following Chisholm from the announcement of her candidacy in January to the Democratic National Convention in Miami, Florida in July, the story is like her- fabulous, fierce, and fundamentally “right on.” Chisholm’s fight is for inclusion, as she writes in her book The Good Fight (1973), and encompasses all Americans “who agree that the institutions of this country belong to all of the people who inhabit it.”

In the early 70s, Cathy Rush becomes the head basketball coach at a tiny, all-girls Catholic college. Though her team has no gym and no uniforms — and the school itself is in danger of being sold — Coach Rush looks to steer her girls to their first national championship.

Writer/Director Jennifer Siebel Newsom brings together some of America’s most influential women in politics, news, and entertainment to give us an inside look at the media’s message. Miss Representation explores women’s under-representation in positions of power by challenging the limited and often disparaging portrayal of women in the media. As one of the most persuasive and pervasive forces in our culture, media is educating yet another generation that women’s primary value lies in their youth, beauty and sexuality—not in their capacity as leaders. Through the riveting perspectives of youth and the critical analysis of top scholars, Miss Representation will change the way you see media.

|

| Winter’s Bone |

In his NYT review of Toe to Toe, A.O. Scott says

If “Toe to Toe” were a young-adult novel, it would be embraced and argued about in classrooms and eagerly read by thoughtful teenage girls. The film’s observations about race, class and friendship are clear and accessible without being overly didactic, and its sometimes harsh candor about female sexuality would not be unfamiliar to devotees of contemporary adolescent literature. But because it is a movie — the first nondocumentary feature film by the writer and director Emily Abt — “Toe to Toe” is likely to languish in art-house limbo, far from the eyes of its ideal audience.

Tosha (Sonequa Martin) is a poor African American girl in a private prep school who is pushed by her grandmother (Leslie Uggams) to believe in herself and her ability to get into Princeton. She also encourages her to play lacrosse because no African American girls do. It is on that field that she meets Jesse (Louisa Krause) a troubled, sexually provocative white girl who has been kicked out of many schools. Jesse and Tosha are drawn to each other and become friends even while the outside world is conspiring against them. But like most teenage girls they also compete. Their friendship is messy, and at times disappointing and destructive. But they try, which is more than can be said for Jesse’s busy single working mom (Ally Walker) who is so oblivious to her daughter’s needs and desperation that you want to throttle her.

Last week, I saw the much-anticipated film Precious: Based on the Novel ‘Push’ by Sapphire. And I haven’t stopped thinking about it all week. Not because I’m in shock, though the film does depict a number of truly horrific and violent situations. And not because I’m blinded by completely uncritical love, because the film is far from perfect, and I recognize that. The reason Precious has stuck with me is because it is, by all accounts, an extremely well-made film. The acting is tremendous and the visuals feel authentic. And, best of all, the film is filled with strong, nuanced, and interesting female characters. In a time when women are often relegated to forgettable romantic comedies and bit parts in “male-centric” films, and when plus-sized women and women of color barely star in mainstream films at all, Precious is a welcomed break from typical multiplex fare.

I want to start by addressing the criticisms of Precious, because many of them are valid. The material is bleak — at times, perhaps, too bleak. Considering the lack of decent portrayals of people of color in film today, do we really need another film that highlights all the most negative things that might happen to a young woman of color?

From Racialicious:

So when I found out Push was being adapted for the silver screen, I cringed at the prospect of revisiting Precious’s bleakly rendered world. I dreaded watching in technicolor all the awful things I’d imagined while reading. And I reeeally didn’t want to return to the hollowness that haunted the ending. What possible reason would Hollywood have for further dramatizing an existence as heinous as Precious’s?It was certainly something to think about. Black American dramas have the tendency to pull their viewers into dark corners and assault them. The grittiest ripped-from-the-headlines realities and the woes so commonplace the news doesn’t bother covering them at all bogart their way into our fiction. Push will be no exception and I wasn’t sure if I should be pleased about that.

And, at the same time, the response to the film, though overwhelmingly positive, has tended to be superficial. As Latoya writes:

While Precious puts forth an array of issues, these are not engaged with by the reviewers. Is it because of the heaviness of the subject matter? Perhaps. But I find it interesting that I have seen more discussion of Mariah Carey appearing without make-up than any discussion of the underlying issues in the film.

Finally, there is the significant issue of colorism. Though Precious Jones has dark skin, the women of color who help her have light skin. While this is problematic all on its own, it’s even more of an issue when one considers that this casting doesn’t actually reflect the character descriptions in the book Push. Feministing has more:

In the book, the description of Blue Rain, the half-messiah, half-educator that delivers Precious from the bondage of illiteracy and abuse is as follows: “She dark, got nice face, big eyes, and…long dreadlocky hair.” (39-40) This character in the movie is played by Paula Patton, a light-skinned African American woman with straightened hair. By no means do I doubt the talent of Patton, but it means something that the directors chose to cast one of the most central characters of the film against Sapphire’s original description.

None of these issues can be ignored in discussing this film. And, sadly, these are the problems that will prevent Precious from being a great film, rather than just a very good film. In particular, I wonder why the decision to cast Paula Patton and Mariah Carey was made. While both women deliver fantastic performances, it’s hard to believe that there weren’t any actresses of equal talent who fit more closely to Sapphire’s descriptions. Though I haven’t read Push, it is my understanding that Blu Rain (the character played by Patton) is meant to be the positive embodiment of everything Precious dislikes in herself and her mother. The casting of a light-skinned woman makes this point much less clear, and it’s disappointing that Lee Daniels and the others involved in the casting of Precious didn’t do more to be true to Sapphire’s intents.

All that being said — Precious is still a very, very good film. Both Gabourey Sidibe and Mo’Nique deliver career-defining performances; this was Sidibe’s first film, and I hope we’ll be seeing much more of her in the coming years. And all of the female characters, including Precious, her mother, Blu Rain, Mrs. Weiss (a social worker, played by Carey), and the other girls in Precious’ GED class, are well developed and complicated. For instance, though Precious’ mother is characterized as a villain, I don’t think she can be seen in such polarizing terms. Though she commits horrible acts of violence and abuse against Precious throughout the film, we learn that there’s more to her than meets the eye and that her actions (as horrifying as they may be) are motivated by her own fears and insecurities. She may be a villain, to some degree, but she isn’t evil — much like Precious, she’s a victim of her own circumstances, and she is forced to make difficult choices. A similar character in another film may be depicted as completely one-dimensional, but Mo’Nique’s performance shows us that there is more to this woman — and to all of the women in the film, for that matter — than what initially appears on the surface.

Another strength is the way in which Precious handles its subject matter. Certainly, all of the issues addressed in the film — including (but not limited to) rape, incest, teen pregnancy, poverty and illiteracy — have been addressed before by other films, and when addressing such topics, it’s all too easy to come off sounding preachy or melodramatic. Precious does not fall in to this trap. Precious addresses these topics honestly and directly, never undermining the horror of it all but still making it clear that these are real aspects of life, and that they aren’t death sentences. Though the character Precious is forced to deal with a huge number of issues that no young woman should ever need to face, the audience is not supposed to pity her. Precious is too strong a character for that. Though the film ends on an ambiguous note, I left the theatre confident that she would go on and do well in life, because I had just spent the past two hours watching her face incredible odds and constantly surviving them with grace. We don’t want to see Precious experience all of the terrible situations she encounters, but we never fear or doubt her. She is clear-headed and determined, and she is a fantastic role model for all young women, from all walks of life. And we ultimately feel empathy, not pity, for her.

If you haven’t had an opportunity to see Precious, I highly recommend checking it out. It’s a flawed film, and it’s not something that will appeal to everyone. But for all its faults, Precious remains a strong film that addresses a wide variety of issues that need to be discussed candidly in film more often. And, if nothing else, it’s bound to be one of the most feminist movies you see this year.

I had a discussion with my husband after the film, and pointed out that most women perceive themselves as the protagonists of their own lives, not as an avid audience for men as they play out their stories. My experience throughout my life when watching movies like this has been to desperately try to find a place for myself among the male characters …

… The sad thing about this film is that I could have really enjoyed it otherwise. As I was watching it I wondered why I was feeling so fatigued, and I realized it was because it was yet another time that I was expected to happily stand in the sidelines and watch boys have lots of fun. That’s such a bummer to me nowadays that I can’t even pretend to be enthused anymore.

Male-Driven Film Nominees

Humpday: Two guys take their bromance to another level when they participate in an art film project.

Big Fan: Paul Aufiero, a hardcore New York Giants football fan, struggles to deal with the consequences when he is beaten up by his favorite player.

A Serious Man: A black comedy set in 1967 and centered on Larry Gopnik, a Midwestern professor who watches his life unravel when his wife prepares to leave him because his inept brother won’t move out of the house.

Two Lovers: A Brooklyn-set romantic drama about a bachelor torn between the family friend his parents wish he would marry and his beautiful but volatile new neighbor.

A Single Man: A story that centers on an English professor who, after the sudden death of his partner tries to go about his typical day in Los Angeles.

The Messenger: An American soldier struggles with an ethical dilemma when he becomes involved with a widow of a fallen officer.

Easier With Practice: In an effort to promote his unpublished novel, Davy Mitchell sets out on a road trip with his younger brother.

Crazy Heart: Bad Blake is a broken-down, hard-living country music singer who’s had way too many marriages, far too many years on the road and one too many drinks way too many times. And yet, Bad can’t help but reach for salvation with the help of Jean, a journalist who discovers the real man behind the musician.

Anvil: At 14, best friends Robb Reiner and Lips made a pact to rock together forever. Their band, Anvil, hailed as the “demi-gods of Canadian metal,” influenced a musical generation that includes Metallica, Slayer, and Anthrax, despite never hitting the big time.

More Than a Game: This documentary follows NBA superstar LeBron James and four of his talented teammates through the trials and tribulations of high school basketball in Ohio and James’ journey to fame.

Un Prophete: A young Arab man is sent to a French prison where he becomes a mafia kingpin. (French/Arabic/Corsican)

Adventureland: A comedy set in the summer of 1987 and centered around a recent college grad who takes a nowhere job at his local amusement park, only to find it’s the perfect course to get him prepared for the real world.

The Vicious Kind: A man tries to warn his brother away from the new girlfriend he brings home during Thanksgiving, but ends up becoming infatuated with her in the process.

Cold Souls: Paul Giamatti stars as himself, agonizing over his interpretation of “Uncle Vanya.” Paralyzed by anxiety, he stumbles upon a solution via a New Yorker article about a high-tech company promising to alleviate suffering by extracting souls.

Bad Lieutenant: While investigating a young nun’s rape, a corrupt New York City police detective, with a serious drug and gambling addiction, tries to change his ways and find forgiveness.

Female-Driven Film Nominees

Sin Nombre: Honduran teenager Sayra reunites with her father, an opportunity for her to potentially realize her dream of a life in the U.S. Moving to Mexico is the first step in a fateful journey of unexpected events. (Spanish)

Precious: In Harlem, an overweight, illiterate teen who is pregnant with her second child is invited to enroll in an alternative school in hopes that her life can head in a new direction.

Amreeka: A drama centered on an immigrant single mother and her teenage son in small town Illinois. (English/Arabic)

Everlasting Moments: In a time of social change and unrest, war and poverty, a young working class woman, Maria, wins a camera in a lottery. The decision to keep it alters her whole life. (Swedish/Finnish)

The Maid: A drama centered on a maid trying to hold on to her position after having served a family for 23 years. (Spanish)

Mother: A woman is forced to investigate a murder after her son is wrongfully accused of the crime. (Korean)

An Education: A coming-of-age story about a teenage girl in 1960s suburban London, and how her life changes with the arrival of a playboy nearly twice her age. (English, from the UK)

Ensemble-Driven Film Nominees

The Last Station: The Countess Sofya, wife and muse to Leo Tolstoy, uses every trick of seduction on her husband’s loyal disciple, whom she believes was the person responsible for Tolstoy signing a new will that leaves his work and property to the Russian people.

500 Days of Summer: An offbeat romantic comedy about a woman who doesn’t believe true love exists, and the young man who falls for her.

Paranormal Activity: After moving into a suburban home, a couple becomes increasingly disturbed by a nightly demonic presence.

Which Way Home: Which Way Home is a feature documentary film that follows unaccompanied child migrants, on their journey through Mexico, as they try to reach the United States. (English/Spanish)

October Country: October Country is a beautifully filmed portrait of an American family struggling for stability while haunted by the ghosts of war, teen pregnancy, foster care and child abuse.

Food, Inc.: An unflattering look inside America’s corporate controlled food industry.

The ecumenical jury—which gives prizes for movies that promote spiritual, humanist and universal values—announced a special anti-award to Antichrist.“We cannot be silent after what that movie does,” said Radu Mihaileanu, a French filmmaker and head of an international jury that announced the awards Saturday.

In a statement, Mihaileanu said Antichrist is “the most misogynist movie from the self-proclaimed biggest director in the world,” a reference to a statement by Danish filmmaker Lars Von Trier at a post-screening news conference. The movie, Mihaileanu added, says that the world has to burn women in order to save humanity.

And, the New York Times article, “Away From It All, in Satan’s Church” by Dave Kehr summarizes the film as follows:

Antichrist is the story of a woman (Ms. Gainsbourg) who blames herself for the accidental death of her young son. With her husband (Willem Dafoe), a cognitive therapist, she retreats to a cabin in the woods with the hope of working through her debilitating grief. But rather than a source of calm and comfort, the forest manifests itself as an infernal maelstrom of grisly death and feverish reproduction. Seeing herself as another “bad mother,” Ms. Gainsbourg’s nameless character identifies with this nature, red in tooth and claw, and descends from depression to insanity. “Nature is Satan’s church,” she proclaims, before moving on to acts of worship that will have some viewers looking away from the screen (if not fleeing the theater).

Great, another film about a woman falling victim to the Bad Mother complex while her husband desperately tries to save her from her inability to not get all irrational and insane and shit. But what I find so interesting about the controversy surrounding Von Trier’s latest probable woman- hatefest (see Dancer in the Dark and Dogville for similar themes) is that many people who’ve seen it argue that Antichrist actually takes religion to task, illustrating its harmful contribution to the continued second-class citizenship of women.

I haven’t even seen this yet (will I?) and I’m skeptical to say the least. A film that, according to Cannes judges, positions a woman as essentially evil, unapologetically physically abusive to her husband, and in the end, so self-loathing that she cuts off her own clitoris, well, yeah, I’ve got some skepticism about the whole “but he’s merely exploring misogyny!” theme. However, through my web and blogosphere research, I’ve found that many reviews and articles attempt to argue that exact point—Von Trier’s latest film has nothing to do with misogyny.

Take a look at some of the following excuses I mean apologies I mean theories about Antichrist and the description of how it actually (heh) portrays women (or how it doesn’t intend to say anything about women at all).

Landon Palmer at Film School Rejects writes:

Antichrist has received many an accusation of being misogynistic. There’s certainly an argument to be made there, and the film will no doubt become a central text in feminist film theory and criticism, coupled with von Trier’s history of treating his lead actresses in not the most respectful manner (many of which have consequently resulted in some of the best performances of their careers, including Gainsbourg’s). But to call Antichrist misogynistic is like saying American Beauty is a movie the champions pedophilia. Just because the idea is introduced and explored does not mean the standpoint of the film, the filmmaker, or how we perceive the film simply and directly runs in line with that. To make such an accusation is dismissive and simplistic, ignoring the many of ideas going on in a film whose central flaw lies in its very ambition. That the message of Antichrist is confused and muddled is a reaction to be expected, but the accusation of misogyny entails a frustrated preemptive refusal to explore the film any further. If Antichrist should be lauded for anything, it’s the many debates on sexism, the depiction of violence, the responsibility and influence of the filmmaker, and the important differences between meaning intended by the filmmaker and meaning interpreted by the audience. But the only way these debates can be constructive is if one genuinely attempts to view this film outside its now-notorious knee-jerk reactions at Cannes and take it at face value.

I agree—the debate is refreshing. We’re actually talking about misogyny. In film. But why the desperate attempts to defend Antichrist against accusations of misogyny? Have these defenders gone to the movies lately? You can’t even see a movie that doesn’t on some level reflect our cultural values and beliefs, and unfortunately, we live in a society that still strongly portrays women in film through embarrassingly and unapologetically sexist, misogynist stereotypes. And they especially run rampant in the supposed oh-so-inoffensive, “perfect date movie!”: the romantic comedy. (To be honest, I often wonder if these supposed film critics can even identify misogyny.)

But perhaps more important than the apologism of critics like Palmer: Von Trier actually hired a misogynist consultant who took part in an interview regarding her role in researching centuries worth of misogyny (so that he could include it in the film). In the interview, she says:

Antichrist shows completely new aspects of woman and adds a lot of nuance to von Trier’s earlier portraits of women, but you can’t really tell from his films what his own actual view on women is, just like you can’t conclude from Fight Club that Palahniuk wants to promote more violence in society. Art doesn’t work that way. The good question is why it is such a provocation for so many to be confronted with the image of woman as powerful, sexual and even brutal?

If that weren’t enough, she also wrote her own piece, arguing that:

The indictment against women I composed for Von Trier sums up the many misogynistic views all the way back to Aristotle, whose observations of nature led him to conclude that “the female is a mutilated male”. Should we avoid staring into that abyss or should we acknowledge this male anxiety, perhaps even note with satisfaction that women are mostly described as very powerful beings by these anxious men?

Many of the defenders of Von Trier’s portrayal of women argue that he really attempts to explore people’s relationship to nature, or problems with psychiatry and an over-medicated society, or depression, or how we’re all inherently evil, or that it’s just too brilliant a film to even warrant analysis—it just needs to be experienced. Even Roger Ebert says:

I cannot dismiss this film. It is a real film. It will remain in my mind. Von Trier has reached me and shaken me. It is up to me to decide what that means. I think the film has something to do with religious feeling. It is obvious to anyone who saw “Breaking the Waves” that von Trier’s sense of spirituality is intense, and that he can envision the supernatural as literally present in the world.

But others came away from the film with an entirely different interpretation of being “shaken.” One of the most thought-provoking pieces I came across was an article in The Guardian, which asked several women—activists, artists, journalists, professors, and actors—to respond to Antichrist. Surprisingly, I felt like most of them dodged the “Is it misogynistic?” question by either choosing not to go there at all or barely glossing over it. Julie Bindel, however, had this to say:

No doubt this monstrous creation will be inflicted on film studies students in years to come. Their tutors will ask them what it “means”, prompting some to look at signifiers and symbolism of female sexuality as punishment, and of the torture-porn genre as a site of male resistance to female emancipation.It is as bad as (if not worse than) the old “video nasty” films of the 80s, such as I Spit On Your Grave or Dressed To Kill, against which I campaigned as a young feminist. I love gangster movies, serial killer novels and such like. But for me they have to contribute to our understanding of why such cruelty and brutality is inflicted by some people on others, rather than for the purposes of gruesome entertainment. If I am to watch a woman’s clitoris being hacked off, I want it to contribute to my understanding of female genital mutilation, not just allow me to see the inside of a woman’s vagina.

Alas, I haven’t seen the film. And because of that, I don’t have much commentary to offer, other than the opinions of the critics who have seen it, and to say that getting people talking about misogyny in film certainly pleases me. However, the over-intellectualization of films like Von Trier’s (and Tarantino’s and other misogynist directors) irritates me not only because it tends to dismiss accusations of misogyny with “but you just don’t get it!” language, but critics who use that language also fail to convey what, for them, would actually qualify as misogyny.

I personally can’t name the last film I watched where I couldn’t identify at least some form of misogyny, the most “harmless” of which (romantic comedies, bromances, Apatow) get rave reviews from critics with rarely a mention of the extremely detrimental portrayals of women as one-dimensional sidekicks, either virgins or whores, love interests, nagging wives, irrational/insane and conniving, etc. So, maybe another question to ask is, why should I trust them in this debate at all?

Regardless, check out the links below for more commentary on the film.

Antichrist shows that men have objectified women as being closer to nature because of their roles as mothers and their natural cycles; and while that can sometimes be seen as a positive stereotype Antichrist makes the case that this particular objectification also renders women terrifyingly alien to men by linking them to the darker aspects of nature that men universally fear.

The notion of the ‘punishment of women’ in his work is not only the outworking of themes dealing with patriarchal oppression, but it juxtaposes the brutality of the world (power, money, hatred, etc) with the spiritual (forgiveness, love, transcendence, etc). While there’s nothing original about this, it seems (judging by reviews) that many people simply don’t get it.

Some critics say that the film is misogynist because the mother takes on to herself all the guilt and blame for the loss of her child, while the father seems almost completely untouched by it. I’d say that sounds rather more like misandry, but what do I know?

Like a number of Von Trier’s films, Antichrist too can and has come under the scanner for its alleged misogyny. While the aggressor in this film, be it in terms of sex or violence, is the woman, seeing her as the Antichrist would do the film a great deal of injustice. Von Trier has certainly moved on from the helpless Golden Heart(ed) girl as a protagonist, and this time around, he doesn’t have an agenda.

Just as much as Antichrist is sure to provoke debate, it is likely to provoke disdain. Despite providing a historical context (both in the film and in his own body of work) to explain his misogynistic premise, von Trier has already been attacked as a misogynist. Such a reading of Antichrist is oversimplified. This is a movie that dares audiences to declare either one of its characters an aggressor, especially since it situates each of them in a realm that shows nature to be just as aggressive itself.

If Antichrist escapes being labelled a misogynist film, Gainsbourg’s fiercely committed screen presence will be the main reason—you sense she’s in control of this character in a way Von Trier isn’t. Indeed, that’s the other reason it’s hard to call Antichrist misogynist: Von Trier made it on such an instinctive level, apparently even incorporating images from the previous night’s dreams into that day’s shooting, that I’m not sure he consciously intended it to be either misogynistic or feminist.

Dafoe elaborated: “It’s not saying anything about women. It doesn’t speak. It’s telling you a story that evokes many things. It’s telling you things about the relationship between men and women. I think Lars has a very romantic idea about women, and in this configuration the man is the rational guy, the fool who thinks he can save himself, and the woman is susceptible to things magical and poetic. And she also suffers from an illness. He’s identifying with women.”

He added that just because misogynistic things might happen in the movie, it doesn’t condone or encourage that attitude. “A woman being self-hating can happen, without saying that’s the nature of women.”

Here is a film that explicitly confronts the director’s intertwined fears of primal nature and female sexuality. But does a fear of femaleness automatically equate to hatred? I’m not convinced that it does. Yes, the “She” character is anguished and irrational; a danger to herself and those around her. And yet for all that, she proves more vital, more powerful, and oddly more charismatic than “He”, the arrogant, doomed advocate of order and reason.

The actresses who have worked alongside Von Trier often attest to his bizarre relationship with women. Kidman famously asked the director why he hates women, while Bjork was so disturbed on set that she began to consume her own sweater. All that highly negative press is probably what led to Von Trier hiring a misogyny specialist for his latest film, ‘Antichrist.’ But he needn’t have bothered. Anyone in their right mind (i.e. none of the characters in the film) would realize this movie is not about men or women, at all, but about the repercussions of depression. Misogyny requires a certain commitment to hating women while anyone who knows anything about depression is aware that those afflicted with it have no attachment to anything at all.