|

| Saber Sharifi trains women boxers in The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

This is a guest post by Rachael Johnson.

|

| Image from The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

|

| Image from The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

|

| Image from The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

The radical notion that women like good movies

|

| Saber Sharifi trains women boxers in The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

This is a guest post by Rachael Johnson.

|

| Image from The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

|

| Image from The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

|

| Image from The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

|

| Fill The Void film poster. |

|

| Shira (Hadas Turon) and her mother (Irit Sheleg) play supermarket spy. |

|

| Shira (Hadas Turon) holds the bay with her mother (Irit Sheleg) looking on and Yochay (Yiftach Klein) looking pensive. |

|

| Shira’s mother (Irit Sheleg), Shira (Hadas Yuron), and Shira’s cousin, Frieda (Hela Feldman). |

|

| Yochay (Yiftach Klein) & Shira (Hadas Yuron) become an instant family. |

“I’m a storyteller more than anything, and I realized that we had no cultural voice. Most of the films about the community are done by outsiders and are rooted in conflicts between the religious and the secular,” says Burshtein, 45, mother of four who was born in New York and lives in Israel. “I wanted to tell a deeply human story.”

| Fill The Void actress Hadas Yuron (left) with screenwriter/director, Rama Burshtein. |

|

| How to Lose Your Virginity poignantly points out that in our culture, if you are a woman and have sex, you’re doomed, and if you don’t have sex, there’s something wrong with you. |

My favorite part of this film is that it is upbeat from start to finish. There’s no anger, there’s no judgment. I don’t want to riff on the “angry feminist” stereotype, but I know I tend to get pretty worked up and, well, angry when I talk about our culture’s toxic obsession with female sexuality and expectations of virginity. Shechter’s ability to teach, dismantle, expose and explore is remarkable. The audience is left with newfound knowledge with which they can criticize myths of virginity in our culture. However, the audience is also left with respect for everyone’s stories–those who are remaining virgins (no matter their personal definition), those who don’t and those who have no idea what it all even means. When a documentary can do that, it succeeds in a big way.

|

|

The phrase “purity balls” will never not make me giggle.

|

Throughout How to Lose Your Virginity, Shechter establishes common ground and values every individual’s experience, criticizing only the cultural myths that make us feel fear and shame about our sexuality. Even when she tackles pornography and purity balls, she does so with respect and cultural criticism, not disdain.

|

| The Grey Area: Feminism Behind Bars promotional still. |

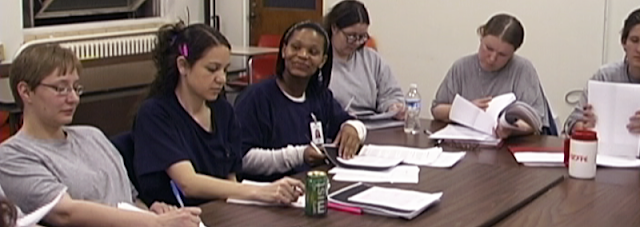

“I wanted to make a documentary about my experience there because I had a feeling that teaching a feminism class at the women’s prison would be a good framework to talk about women’s issues in the criminal justice system in general and to bring the stories of these women to the public through this film.”

|

| The documentary was filmed at the Iowa Correctional Institute for Women. |

|

| These women’s stories were highlighted throughout the documentary. |

|

| The Lifeguard movie poster. |

|

| “I’m the fucking lifeguard, motherfuckers.” |

|

| Leigh attempts to guide Jason (David Lambert) into better life choices. Their relationship is disturbing, sexy, destructive and strangely realistic. |

In The To Do List, Brandy says, “Teenagers don’t have regrets–that’s for your 30s.” Leigh is trying desperately to hold on before her 30s hit.

|

| Night-swimming in the pool–Leigh is caught between rules and control and wildness. |

|

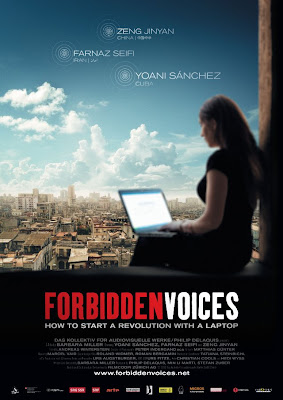

| Forbidden Voices movie poster. |

Written by Leigh Kolb

|

| Yoani Sanchez |

|

| Farnaz Seifi |

|

| Zeng Jinyan |

Forbidden Voices is a selection from Women Make Movies, an organization that “facilitates the production, promotion, distribution and exhibition of independent films and videotapes by and about women.”

|

| Salmai movie poster. |

Written by Leigh Kolb

|

| Salma, a Tamil poet and politician. |

|

| Salma still must confront resistance from her family and the next generation. |

|

| Kristen Wiig as Imogene in Girl Most Likely |

Written by Lady T.

|

| These two women in the same movie? Sign me up! |

|

| I’m sorry, I lost my train of thought for a minute. |

|

| Imogene talks to her brother’s crush. (Don’t get too excited to see Natasha Lyonne – this is, like, her only scene in the movie.) |

|

| Lee is really into her, for some reason. |

|

| Imogene is depressed. So am I, but for a different reason. |

|

| The To Do List. |

|

| “Sisters before misters”–best friends Fiona (Alia Shawkat), Brandy (Aubrey Plaza) and Wendy (Sarah Steele). |

|

| Brandy takes notes as her older, experienced sister (played by Rachel Bilson) talks about sex. |

|

| Brandy’s “To Do List” replaces buying shower shoes for the dorm with sexual exploits. |

The film also really has a “radical” message about virginity–not panicked, not preachy, but reasonable and realistic. Maybe most importantly, Brandy never has any regrets (“Teenagers don’t have regrets,” she says. “That’s for your 30s”). The To Do List is “nonchalantly” feminist from start to finish.

“When I read the script, I just thought it was funny, be it female or male, but I love that it was from a female perspective, and I’d honestly never seen anything that had explored the specifics of that time in a girl’s life when they’re experiencing all their firsts.”

|

| “It’s a skort!” (And who doesn’t want to make out to Mazzy Star?) |

|

| Farah Goes Bang movie poster |

“I wanted to do something I hadn’t done before. Change the world and be awesome.” – 17 year-old female John Kerry Campaign Volunteer in Farah Goes Bang

“Their odyssey through the heartland of America is meant to demonstrate the ways in which these girls are often not seen as American, though they are as American as any other. I really wanted the film to integrate their faces and races into a new sense of American identity, one that embraces the hybrid, cross-cultural form that I have experienced in my own sense of citizenship.”

|

| “I think [the scarf] looks pretty, kinda like it belongs on you.” – KJ “That is so racist.” – Roopa |

Farah Goes Bang passes the Bechdel test all day long. The core of this film is the connection between these three women and how it supports them, gives them strength, allows them their fluidity of identity, and is fun as well as necessary for each of their unique journeys. Menon says,

“The film, at its heart, is about the importance of female friendships during the rapid period of personal growth that is your twenties. I have learned so much through my friends, particularly female, about who I am and the woman I hope to be. This film is a love letter to how formative those relationships are when you are young.”

|

| KJ, Farah, and Roopa enjoying a special night of anticipation and fireworks. |

|

| Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson) and Bob (Bill Murray) in Lost in Translation |

|

| Bob Harris (Bill Murray) stands tallest in a Japanese elevator |

|

| Charlotte looks out at Tokyo from her hotel room window |

|

| Directions during a whiskey ad shoot are literally lost in translation |

|

| Scarlet Johansson spends a lot of this movie looking out of windows. |

|

| Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson) and Bob (Bill Murray) in Lost in Translation |

|

| Bob and Charlotte say goodbye. |

|

| Agnès Varda directs Vagabond |

|

| Sandrine Bonnaire as Mona Bergeron in Vagabond |

|

| Mona drinks with a wealthy older woman |

|

| Sandrine Bonnaire in Vagabond |