|

| Geena Davis as Thelma and Susan Sarandon as Louise |

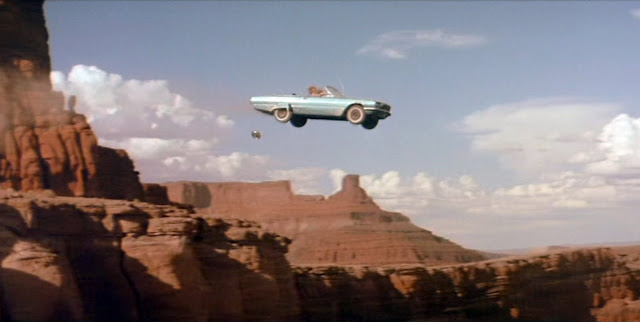

After its release in 1991, Thelma & Louise stirred up controversy mainly surrounding its connection to feminism, its use of violence, and its presentation of male characters.[i] It was criticized for its portrayal of men as one-dimensionally negative. The two heroines were accused of male bashing. It was condemned for advocating violence as a solution to women’s problems. Over twenty years later, though, I think that Thelma & Louise is most often thought of as a wild, raucous outlaws-on-the-run movie, but with girls. A buttered-popcorn, butt-kicking chick flick about female empowerment. Two strawberry blondes in a sea-foam T-bird convertible. Lite feminist fizz.[ii] It’s unthreatening. And yet, it threatens me.

I find it deeply and profoundly scary.

Chrissy and I watching it, drinking whole bottles of vodka in my studio on Mission Street. Her curly hair/my straight hair.

We called it a horror movie.

Because of the end. Because they almost made it. Because they maybe could’ve made it. Because they never could’ve made it. Because the world we live in wouldn’t have let them. And because they knew it.

|

| Still from Thelma & Louise |

It threatens me because it happens in my world too. It obscures my view.

When Thelma says shouldn’t we go to the police & Louise says we just don’t live in that kind of world.

When Thelma says how do you know ‘bout all this stuff anyway.

When Thelma says it happened to you, didn’t it.

The trail of breadcrumbs starts with rape & the thread is a product of rape.

They follow the thread in circles, refusing to go through Texas.

|

| Still from Thelma & Louise |

In Europe when Jenny and I slept in the same bed every night even though there were two.

How in Spain Lana and I would sit in coffee shops for hours and get drunk on the beach and take pictures in Zara.

When we were in Western Mass and Tina brought me to the train and I didn’t want her to leave.

|

| Geena Davis as Thelma in Thelma & Louise |

|

| Thelma and Louise being pursued by police |

If men didn’t rape, Louise wouldn’t have shot the rapist. If the system didn’t blame rape victims, they wouldn’t have gone on the run. If men didn’t rape, they could have driven through Texas. If the system didn’t blame rape victims, Louise wouldn’t have been so afraid. If women weren’t taught they deserve to be treated like shit, they wouldn’t have had to become fugitives in order to feel free. If there was a place for liberated, powerful women who live on their own terms in this world, they wouldn’t have had to create their own. If there was a place for liberated, powerful women who live on their own terms in this world, they wouldn’t have had to plummet into the Grand Canyon in order to feel free.

The logic falls in on itself. Like a sea-foam T-bird falling into the Grand Canyon.

When there’s a wall of cop cars behind them and the canyon is in front of them and Thelma says let’s keep goin’.

|

| Thelma with a gun |

It shows the car falling all the way into the canyon instead of freezing the frame with the car in mid-air, flying outward on an upswing. Watch it. Because you can see the car getting smaller and smaller, as the canyon gets bigger and bigger. And it starts falling at an angle that no longer looks controlled, no longer looks triumphant. Which is exactly how it should look — the logical conclusion that joyful, strong women have no place in this world.

The way they freeze the frame with the car on an upswing at the end is why people call Thelma & Louise a “chick flick.” It’s why it’s remembered as a girl power-powered outlaw movie, rather than a horror one.

How me and Carrie wrote a song about Kim while she was in the other bedroom.

When Tina and I were drinking sangria in San Francisco, and we couldn’t stop prank-calling you and laughing into our sleeves.

How we were in the Catskills and I yelled at Janie, well why don’t you just eat.

|

| Louise with a gun |

Before the credits start to roll, the white screen flashes with a montage of images showing the two women, happy and alive, suggesting a weird kind of magical realism.

It’s all in that phrase: let’s keep goin’. As if by driving off the cliff they really did keep going. As if they had reached a parallel universe in which their journey did not have to end. It reminds me of the end of Pan’s Labyrinth, before the little girl is shot in the labyrinth. In the scene where we see her stepfather watching her talking to thin air, we see a crack in the magic into a horrific reality. The last scene in Thelma & Louise shows no definitive cracks in the magic. Only a triumphant freeze-frame that loops back almost instantly to images of the heroines’ lives.

I think, for instance, of two movie heroines, born-again desperadoes, who smash one limit after another, uncover the hidden places where anger and despair, defiance and love converge, and finally leap into the Grand Canyon because freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.

I can’t decide if I think Willis is letting the film off too easy here, but I love this comparison anyway. Janis Joplin was real; her struggle was real and her death was real. But for me, growing up in the 80s and 90s, she wasn’t a real woman so much as an icon; a symbol of wild, defiant love and art, tough, complex femininity and unrelenting sexuality, her life remembered for the spirit of freedom that she embodies, rather than for the sense of tragedy. And so are Thelma and Louise, for better or for worse — their car still goin’, the music still blasting, the camera still clicking images of them, first in red lipstick, sunglasses and hair kerchiefs, and later in dirtied jeans and cut-off t-shirts, their hair whipping wildly in the wind.

|

| Thelma & Louise DVD cover |

[ii] “Light feminist fizz” is borrowed from Bill Cosford, Miami Herald movie reviewer

[iii] Roger Ebert, “Thelma & Louise,” Chicago Sun-Times

[iv] Ed. Nona Willis Aronowitz, Out of the Vinyl Deeps: Ellen Willis on Rock Music, University of Minnesota Press