Written by Colleen Martell as part of our theme week on Dystopias.

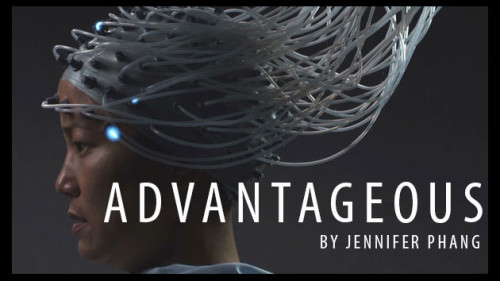

Advantageous, which began streaming on Netflix on June 23, is a dystopian science fiction film that asks, “Are women really going backwards going forward?” It explores this question through the relationship between a single mother, Gwen (played brilliantly by Jacqueline Kim, who co-wrote the film), and her daughter Jules (Samantha Kim, also brilliant), and the painful choice Gwen makes in order to give her daughter a chance at succeeding in a misogynist, racist, ableist, and economically unjust world. It’s a subtle and slow film, as visually beautiful as it is haunting.

Writer and director Jennifer Phang first produced Advantageous as a short film in 2013. The short offers some helpful background information: we learn that the year is 2041; the world population is 10.1 billion, and the U.S. unemployment rate is at a staggering 45 percent. Technology has rapidly advanced. The significance of these facts is fleshed out in the full-length film. Homeless, destitute women people the world of Advantageous. Child prostitution is on the rise. Income inequality has been made drastically worse by the dismantling of the public school system. The only educational opportunity for children who aren’t from elite families is to win a spot in the few remaining magnet schools. Jules doesn’t get into a magnet school, and at the same time Gwen loses her job as the spokesperson for the Center for Advanced Health and Living because they are looking for a younger, “more universal” (which, according to Phang in an interview with Mark Asch at The L Magazine, in this case means “non-specific, multi-racial”) face to market the company.

Advantageous struck me as an incredibly embodied, earthy story. Jules and Gwen are outside in parks a lot, walking through green grass and sitting under tall, shady trees. They listen to music together, eyes closed and breathing deeply. They play piano and sing together sitting shoulder to shoulder; they sleep cuddled in bed together; and they eat pecan pie out of the pan together. Jules is often dancing or drawing. She wants to have children; she wants a big family. Gwen and Jules play a guessing game in their apartment: is it the woman upstairs or downstairs who is sobbing? Sometimes the answer is both. Sometimes the answer is Gwen. We see women sleeping on park benches, living in flower beds. The physicality of women, Asian American, Black, and white women, and of Gwen and Jules’s bond, is palpable.

In contrast, the Center for Advanced Health and Living promises freedom and liberation from bodily limitations: “Be the you you were meant to be.” The Center encourages people of economic means to discard their diseased or disabled bodies, or even just their disliked bodies, and to transcend “race, height, or health” by transferring themselves into “better” bodies. A new body is “a pragmatic response to today’s unforgiving job market,” they promise. Economic disparities and unfair hiring practices got you down? Become someone who is hirable. Their message, propagated by Gwen, is one of empowerment: free yourself from anxiety and depression by overcoming your disadvantages in a new body.

This contrast is one of the film’s most deeply felt questions: if women could change their bodies to fit the latest trend, could they succeed in a discriminatory, patriarchal society? But at what cost?

Gwen’s answer to these questions is complicated. Unable to find work elsewhere, Gwen agrees to be a test subject for the Center’s mind-body transfer so that she can keep her job and put Jules through school. An experienced spokesperson in a younger, more ethnically desirable woman’s body: the perfect employee. Although we might celebrate her sacrifice for her daughter at whatever cost to herself, this act shows Gwen playing along, putting her faith in a system that has not really served her. In agreeing to undergo an extensive, self-altering procedure she in effect tells Jules to also keep playing along. “I can’t let her become one of these women who would do anything,” Gwen explains her choice to her boss at the Center. And yet Gwen is now one of those women, willing to do just about anything the system asks her to do in order to stay afloat in it.

On the other hand, Gwen spends much of the film offering Jules a different narrative. Jules asks her mother, “Why did you have me, when you knew the world was so bad and you had to struggle so much?” She agonizes, “I don’t know why I’m alive.” Gwen answers that life is worth living because of music, good food, and being loved by your mother. The head of the Center, Ms. Cryer (Jennifer Ehle), undermines Gwen’s optimism about finding another job at her age when technology has advanced so much. Gwen pushes back: “There must be something in a mere human existence that has value.” In these moments, and in those unspoken moments when she savors placing long sweet kisses on Jules’s cheek, we see Gwen’s resistance. “Know your value,” Gwen tells Jules. It’s not found in good grades, not in getting into the best school, not in a newer and “better” body, but in sensory and emotional human pleasures.

This double message is what makes the film so heartbreaking: Gwen shows that life is worth living because of all of these embodied experiences, but then she gives up experiencing those things in her own body so that Jules can compete in the socioeconomic system as it is. What we as viewers are witnessing is the deal Gwen strikes between her resistance and her compliance. We are left to wonder if what she got (economic security for Jules) was worth the price she paid (her body).

There are hints of civil unrest all throughout the film. A broadcast refers to a rebel group called the “Terra Mamona” (according to my subtitles) bombing (corporate?) buildings (is this some sort of ecofeminist activist group? A girl can dream). Her boss Fisher (James Urbaniak) informs Gwen that corporations fear what might happen with so many unemployed desperate men on the street, and so “there is talk among recruiters about letting women stay unemployed” and forcing them back into the home in favor of hiring men. In other words, there are dissenters, and if recruiters are afraid that unemployed men will revolt, it’s easy to imagine the unemployed women we see sleeping in flower beds and on park benches organizing their own revolution. Women — specifically women of color — have long been at the forefront of resistance movements in the U.S. and elsewhere, after all.

As a result, I fantasized about a different narrative, one in which Gwen perhaps joins or starts a rebellion, fighting for her right to hold her daughter in her own arms, against exploitative corporations and cost-prohibitive schools and unemployment, fighting with and for the homeless women in the parks. But that is not this story. This story is an allegory of the terrible decisions disadvantaged women are often forced to make in order to survive in a corrupt social structure, clinging desperately to the hope that if they do certain things “right” the next generation will succeed in a system that was set up to fail them. In an interview with Emily Yoshida at The Verge, Phang said that, “most of my life I’ve been trying to humanize and normalize perceptions of people who are not your standard Caucasian-looking American.” If there’s any hope in the film, then, it’s that the loss of the tactile inter-generational bond between Gwen and Jules is so striking that it makes those relationships all the more meaningful in our own place and time.

See also at Bitch Flicks: Leigh Kolb’s “Advantageous: The Future is Now,” and Holly Derr’s “Advantageous: Feminist Science Fiction at Its Best”

Colleen Martell, a writer based in Pennsylvania, is apparently obsessed with watching dystopias this summer (see here and here). Find her on twitter to talk about bodies and film and the end times: @elsiematz.