“How can you be an artist and not reflect the times?”

–Nina Simone

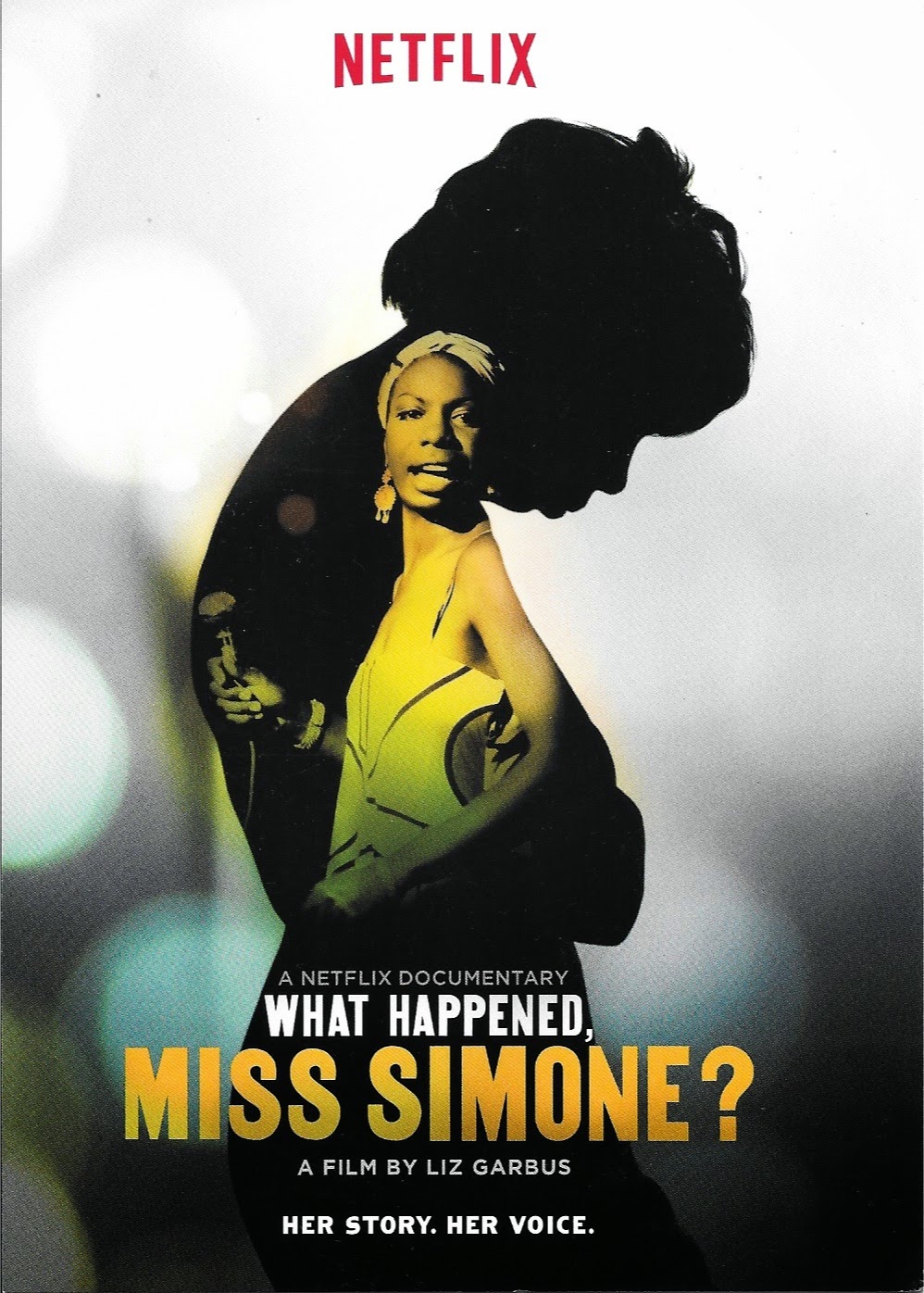

Director Liz Garbus could’ve stopped the documentary What Happened, Miss Simone? six minutes into its run time. Nina Simone steps onstage after a lengthy absence from show business. She takes a bow and then stops cold, stares at the audience for what seems like an eternity. Her eyes take in the scene but from my viewpoint, it looks like she is seeing beyond the crowd gathered before her. It’s like she can see the future, what’s coming up for Black people around the bend of time.

Her face is filled with long simmering rage, pain, insolent dark beauty, and unchecked defiance. Here stands an artist struggling to create timely, relevant, serious Black art in front of an overwhelmingly white audience outside of America. She remembers the feeling of isolation and hatred against her for being Black. Nose too big. Lips too full. Skin too dark. Daring to dream of becoming the first Black classical pianist. Denied entry into the Curtis Institute of Music after a short stint at Julliard. Then she sits down. Speaks a few words, and then starts her performance.

This small moment, a few seconds really, told me all I needed to know. The documentary could’ve ended right there for me, the look on Simone’s face was that forceful and telling. I have seen that look before. In the eyes of my grandfather when I was little, in the eyes of aunts and uncles and older friends who have been through some shit in America. It’s the eyes of a weary soldier who knows the battle will be long and not finished soon enough.

What makes this documentary extraordinary is that we get to hear and see Nina Simone talk about her life herself. In her own words at the exact times she says them. This is not a typical documentary film where the artist is reflecting back, perhaps shading the truth a little because of time. Garbus uses film footage of Nina speaking, and we are allowed to be time travelers, visiting exact moments in Simone’s life as they are happening. Dispersed among the footage are archival glimpses into Nina’s journals, where we can read quick sketches of her own thoughts and feelings. And although the particular journal entries are chosen and shaped to fit the narrative Garbus is presenting, it only helps to give us a deeper understanding of the complexity of being a Black woman artist in racist America. Nothing has changed.

What I enjoy about the documentary is that Nina is bold and Black with no filters, exactly as I imagined her to be. I started listening to her music with serious intent while in college after presenting a paper on protest music in a History for Teachers class. I wrote of folk singers, like Woody Guthrie, Joan Baez, Odetta, et al, moved into James Brown’s seminal “Say it Loud-I’m Black and I’m Proud” and “I Don’t Want Nobody to Give Me Nothing (Open Up the Door, I’ll Get It Myself)” and introduced my professor and classmates to Simone’s “Missississippi Goddam.” No one had heard of the song or her. I dug into music archives, listening, learning, trying to imagine being a singer of righteous indignation in a world that only wanted Diana Ross and the Supremes type pop music from Black women. I wondered what Nina Simone thought about her work going against the musical dictates of her time. In this documentary, Simone lays it out there for me. And it’s a heartbreaking motherfucker to watch. I had to pause several times in my viewing to catch my breath and process Simone’s words. A reporter interviews Simone late in her life and Nina laments that all she wanted to be was that cherished classical pianist, and tears swell up in her eyes. I had to stop and cry for her too.

What Happened, Miss Simone filled me with a lot of anger. I’m angry a lot these days I confess. Angry at the overt racism she lived through, angry at the depression and undiagnosed bipolar disorder she suffered through for so long, and angry at her husband/manager Andrew Stroud. Angry that American racial baggage is still with us as I write these words. The footage of Stroud talking about his life with Nina Simone is a goldmine to have, because we hear directly from the horse’s mouth his adverse reaction to her radicalization during the Civil Rights Movement. In one journal entry Simone wrote:

“I don’t mind going without food or sleep as long as I am doing something worthwhile to me such as this.”

As for her husband’s response to her involvement with the Civil Rights/Black Power Movement, she wrote:

“Andrew was noticeably cold and very removed from the whole affair.”

While Simone stands on stage shaping her music to reflect the times she lives in, hoping to inspire and encourage young people to recognize they were young, gifted, and Black, in a world that wanted to crush the life out of them, Stroud sits on film stating with disdain, “She wanted to align herself with the extreme terrorist militants who were influencing her.”

Here was a Black man who was calling young Black radicals fighting oppression terrorists. Black People. In America. Getting their asses bombed, beaten, and bloodied in the streets of a country they built. Are you out of your cotton-picking mind?

No wonder Nina Simone left Andrew Stroud.

It wasn’t enough that he was beating her, working her to death, and dominating her life. He was disrespecting the work that she found meaningful which was making music for her people. I found it condescending and – surprise- sexist, that he believed Simone had no agency of her own to think for herself. He really believed that others outside of her own thinking mind were influencing her decision to write and sing radical Black music, to take up the cause of the Black Panthers and to question the utility of non-violence in the face of violent white Americans. Theirs was a complicated, volatile relationship, and I could only feel deep sorrow for their daughter Lisa Simone Kelley who was caught in between them. Lisa discusses how she later suffered physical abuse at the hands of her own mother after her parents broke up. (Side note: One of my favorite performances of Simone’s “Four Women” includes Lisa Simone Kelly. Watch it here.)

Simone explains that she was responsible for the livelihood of 19 people who worked for her. The pressure, stress, and physical/mental fatigue made her suicidal. What happens when your soul can’t do what it needs to do? When the thing that you love doing, slowly turns into the thing that you dread and eventually hate? It eats at you and often your mind turns on itself. Another journal entry during this crisis has Simone lamenting, “They don’t know that I’m dead and my ghost is holding on.”

The documentary showcases the highs and many lows, and it gives the viewer an opportunity to glimpse the genius Black woman that Simone was. Her music catalogue and this documentary are like a grimoire for those of us who need to reach into it to conjure up spells of protection and invocations of remembrance. I had to watch it four times to revel in her magic.

Near the end of the documentary Nina reflects on how singing political songs hurt her career.

“There is no reason to sing those songs. Nothing is happening,” she says. She is so wrong. We need her songs now more than ever. We need that bold, bruising canon of radical Black music. We are calling on old Black Gods during this Black Lives Matter Movement (and the racist, terrorist attack on the Emanuel AME church in Charleston, South Carolina that ended nine lives, including that of a State Senator), and this High Priestess of Soul can show us the way.

I hear her influence in the recent works of D’Angelo (the Black Messiah album) and Kendrick Lamar (“Alright”) who are writing protest music for this generation. As writer/cultural critic Stanley Crouch says in the film, Nina Simone is the Patron Saint of the Rebellion. All praises due. The struggle continues. This documentary tells us that. Call upon her name. Nina. Simone.

Amen.

_________________________________

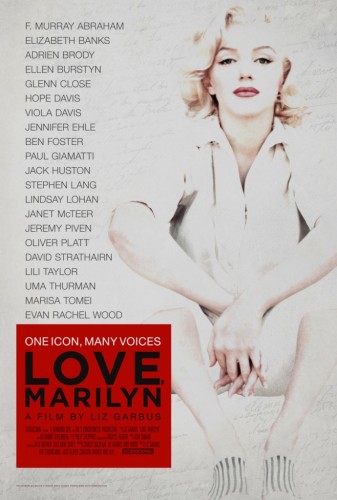

Staff writer Lisa Bolekaja co-hosts Hilliard Guess’ Screenwriters Rant Room, and her latest speculative fiction short story “Three Voices” can be read in Uncanny Magazine. She divides her time between California and Italy. She can be found on Twitter @LisaBolekaja. Follow at your own risk.