Feminist ethics typically defines feminist philosophy as focusing on morality and relationships and not just traditionally masculine justice.

While Les Miserables features female characters who do exist largely to save men, this larger feminism vs. patriarchy dilemma is at work between the ideologies of Jean Valjean and Javert.

A

Washington Post writer

bemoaned how anti-feminist

Les Mis truly is, with its stereotypical women who “exist not to drive the plot but to sacrifice for the men, the real stars of the show.” She refers to them as “bit players” in the musical, and notices that the women are all “abused” and “marginalized.” Yet as a feminist, she can’t help but love it.

While the female characters indeed do suffer to save men, there is much more at play in this film (an adaptation of the stage adaptation of Victor Hugo’s 19th century novel).

From the very beginning, we know that the hero’s journey belongs to Jean Valjean (Hugh Jackman), and that his path of self-realization will be the heart of the plot. After being “saved” by a compassionate priest, he vows to change himself (literally and figuratively, as his convict papers limited his employment possibilities). Eight years later, he has a new name and is mayor of a new town and a factory owner.

Fantine (Anne Hathaway) is a worker in a factory when she is introduced to the audience. The group of women–in sweatshop conditions–sing “At the End of the Day.” The lyrics showcase poverty, a lecherous foreman, hungry children and dismal working conditions. Fantine is fired for hiding that she has a child (the assumption is that she is immoral, which her co-workers pounce on). Valjean does not fight the foreman to keep her employed, and she is fired.

|

| Fantine, in pink, works to support her child. |

Fantine is the ultimate suffering mother, and Hathaway does a remarkable job at portraying her suffering when she chooses (out of necessity) to sell her hair, necklace, teeth and body. “I Dreamed a Dream” was incredible, especially considering the actors sang live during filming. Fantine’s plight is clearly the fault of awful men–the man who impregnated and then left her, the abusive foreman, the disgusting johns–she is a fighting victim, and she has the audience’s sympathies.

When Valjean saves Fantine from Javert (Russell Crowe), who was arresting her because he believed her abusive customer over her, and takes her to the hospital, he realizes that he’d let this happen, albeit passively, and pledges to take care of her daughter.

|

| Fantine’s transformation into a dying prostitute. |

Valjean realizes that he hadn’t done what he should have in the first place, and makes up for it (this is really Valjean in a nutshell). Unlike the strict Javert, who lives rigidly within a patriarchal code of justice, Valjean’s morality grows and evolves, as he questions himself and the world around him.

The film introduces a new song, “Suddenly,” placed after Valjean rescues Cosette from the Thenardiers (Sacha Baron Cohen and Helena Bonham Carter, in roles that seem made for them). As she sleeps, he expresses her transformative effect on him. Having a child gives him new hope and life. He sings, “Suddenly I see / What I could not see / Something suddenly / Has begun.” This stereotypically feminine maternal love for a child changes Valjean.

|

| Cosette and Valjean save one another other. |

Javert identifies Valjean by his brute strength, because that is all he can see in his fight for black and white justice.

In “Stars,” Javert’s ode to order and righteousness, he subscribes to a religion that is authoritative and patriarchal. His views of justice contrast Valjean’s and are deeply rooted in traditional masculinity. Valjean’s religion is about

grace, empathy and compassion, and his justice is not about man’s law, but about morality and care–typically feminine virtues.

|

| Javert, after the revolt. |

Many of us fell deeply in love with

Les Mis as young girls and

“tweens,” and the plights of Cosette dreaming about a castle on a cloud, or Eponine longing for someone in a different world who doesn’t love her back, tugged on our pubescent heartstrings. The music never ceases being beautiful, but as we get older, we understand the larger implications of Fantine’s suffering, Valjean’s existential crises and Javert’s clinging to justice without morality.

The class issues that drive the story are introduced with Valjean and Fantine, and come to a head with the revolt led by university students against the injustice of poverty. Eponine’s (Samantha Barks) unrequited love for Marius (Eddie Redmayne) is painful, but she is still a strong female character. She leads Marius to Cosette (Amanda Seyfried) and fights behind the barricades. The film shows her binding her breasts during “One Day More,” and when she pulls the rifle away from Marius so she is shot, the audience sees it up close. She’s sacrificial, obviously, but independent and strong, doing what she needs to do for her community, herself and Marius. Her plight symbolizes an oppressive system of social classes more than it does weak womanhood.

|

| Eponine, a victim of poverty, terrible parents and unrequited love. |

When Gavroche sings about “little people,” and is eventually killed, he also is a symbol of the evils of oppression.

Cosette and Marius are equally smitten with one another (no games, no desperation). When Valjean learns about their love for one another, he’s in the midst of wanting to flee to get away from Javert. When he hears of the revolt, he goes, largely to protect Marius. He doesn’t know Marius, but he knows his daughter loves him, and that’s enough. He pleads with God to “bring him (Marius) home,” and protect him. When Marius is shot, Valjean saves him anonymously. He loves Cosette so much that he is willing to risk his life for a man who she loves, and he trusts her judgment. Women aren’t the only sacrificial figures here.

Valjean has the opportunity to kill Javert, but refuses. Javert commits suicide when he is faced with an inner conflict that he can’t resolve. Javert sings:

“Damned if I’ll live in the debt of a thief!

Damned if I’ll yield at the end of the chase.

I am the Law and the Law is not mocked

I’ll spit his pity right back in his face

There is nothing on earth that we share

It is either Valjean or Javert!”

This dualistic view of mankind’s nature and society loses–at its own hand. Valjean’s morality overcomes Javert’s strict code of justice.

When Marius and Cosette reunite in “Every Day,” Valjean sings “She was never mine to keep / She is youthful / She is free.” This epiphany should lift up any feminist’s heart, because that’s a pretty refreshing thing to hear from someone, much less a 19th-century father.

|

| Marius and Cosette. |

After they are married, Cosette and Marius find Valjean (who has exiled himself again and is staying in a convent). Valjean gives Cosette a letter with his life story, and as he’s dying, he sees Fantine and the priest and goes toward them.

The ending is a gorgeous reprise of “Do You Hear the People Sing,” as Valjean goes toward an enormous barricade and sees all those who have died. While there has been a great deal of loss throughout the film, this ending is uplifting. The message is that love has prevailed–platonic love, familial love and romantic love.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy defines feminist ethics as questioning traditional ethics:

“…traditional ethics overrates culturally masculine traits like ‘independence, autonomy, intellect, will, wariness, hierarchy, domination, culture, transcendence, product, asceticism, war, and death,’ while it underrates culturally feminine traits like ‘interdependence, community, connection, sharing, emotion, body, trust, absence of hierarchy, nature, immanence, process, joy, peace, and life’ … it favors ‘male’ ways of moral reasoning that emphasize rules, rights, universality, and impartiality over ‘female’ ways of moral reasoning that emphasize relationships, responsibilities, particularity, and partiality (Alison Jagger, ‘Feminist Ethics’).”

Javert clearly embodies traditional, masculine traits and an obsession with rules. Valjean, on the other hand, grows into a sympathetic hero by developing a more feminine morality (putting a priority on connection, questioning hierarchy, working for peace and developing relationships). Valjean is our hero.

While Javert’s Christianity drives his actions (he sings “Mine is the way of the Lord” in “Stars”), Valjean’s stumbling toward Christianity is more authentic and is portrayed as preferable, with a focus on forgiveness, sacrifice and giving. As he’s dying, he sings along with the ghost of Fantine, “To love another person is to see the face of God.” This is the truth we’re supposed to walk away with–not the truth of laws and authority, but the truth of emotional vulnerability and mercy.

The women of Les Miserables suffer and sacrifice for men, and their plights certainly propel the men’s stories. Cosette, who is more one-dimensional than the other women, survives and thrives. She had the privilege of having a good parent and being in love, which again shows the importance of good relationships.

The only way, then, that Les Miserables could be anti-feminist is if Javert and his worldview had won. But he doesn’t; instead, the audience is supposed to celebrate what are often considered culturally feminine traits and morality. Les Miserables is critical of social injustice, poverty and oppression. And at the end of the day, that sounds like feminism.

|

| The barricades are erected and are triumphant at the end of the film. |

—

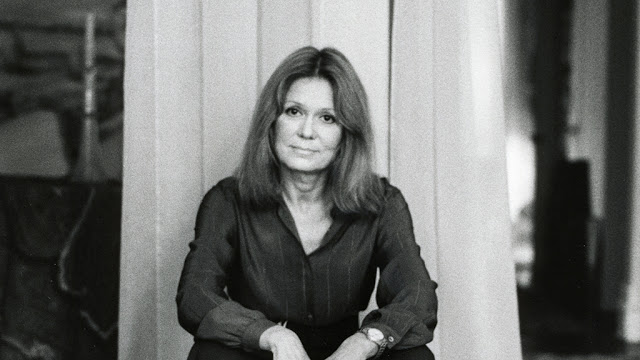

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.