Spoilers ahead

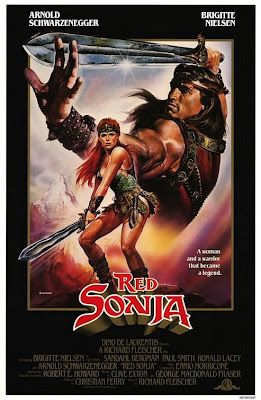

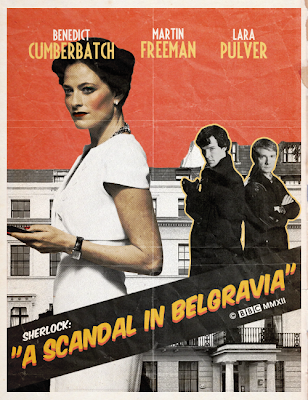

Benedict Cumberbatch is up for another Golden Globe for his leading role on the BBC’s hit show

Sherlock. Season Two Episode One “A Scandal in Belgravia” is adapted from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Holmes story “A Scandal in Bohemia.” The storyline focuses on Irene Adler, portrayed brilliantly by the arresting Lara Pulver, who has incriminating photographs of a member of nobility that Sherlock must retrieve.

In the original version, Adler is an opera singer who had an ill-advised affair with the prince of Bohemia, and he discontinued the affair because he was to become king and thought she was beneath his station. Adler threatens to expose the photos if the now king announces his engagement to another woman. In the updated TV episode, Adler is a high-priced lesbian dominatrix who operates under the pseudonym “The Woman” and holds photos of a high-ranking female member of the British nobility.

|

| Irene Adler: lesbian dominatrix and general BAMF |

Confession: I love Irene Adler. She’s infamous for her sensuality, independence, intelligence, and her ability to manipulate. Throughout the episode, Adler and Sherlock match-up wits, and Adler proves to be the cleverer one right until the very end. Adler establishes herself as the quintessential femme fatale. When contrasted with the other female characters throughout the series, she is the only one who is given a strong representation. The coroner, Molly Hooper, is a doormat, waiting for Sherlock to notice her and her inexplicable affection for him. Mrs. Hudson is a doddering old lady whom Sherlock abuses but takes umbrage if others treat her in a similar fashion, in a way claiming her as his property to abuse or reward at his own whim. Finally, there’s the recurring character of Detective Sergeant Sally Donovan, a tough, but mistrustful police officer who always thinks the worst of Sherlock and is too simple-minded to follow his deductions.

Though Sherlock doesn’t know it, Adler is well-prepared for their first encounter when Sherlock shows up on her doorstep impersonating a mugged clergyman. In parody of his earlier nude appearance at Buckingham Palace, Adler presents herself to Sherlock in her “battle dress,” i.e. completely naked. This proves to be a cunning ploy because Sherlock can deduce little about her character without the aid of clues from her clothing. Not only that, but Adler maneuvers Sherlock to help her ward off some C.I.A agents by using her measurements as the code to open her booby trapped (har, har) safe. Adler then drugs and beats Sherlock until he relinquishes her camera phone, which contains a host of incriminating evidence that she claims she needs for protection. She ends their memorable first encounter by saying, “It’s been a pleasure. Don’t spoil it. This is how I want you to remember me. The woman who beat you.”

Minus all the sexy dominatrix stuff, this is where the original Holmes story ends. Irene Adler disappears, retaining her protective evidence, and Sherlock must forevermore admire and be galled by The Woman who beat him. The BBC episode, however, takes creative license to continue the story, having Adler fake her own death only to show up six months later demanding Sherlock give back the camera phone that she’d sent to him presumably on the eve of her death. For six months, Sherlock has done his version of mourning, as only an admittedly high-functioning sociopath can (becoming withdrawn, composing mournful violin music, smoking, etc.). Does he mourn, we wonder, the death of a woman for whom he’d grown to care, or does he regret the loose end, the loss of a chance to ever reclaim his victory and trounced ego from such a superior opponent?

Before her faked death, Adler sent frequent flirtatious texts to Sherlock, with the refrain, “Let’s have dinner.” Sherlock responded to none of her messages, lending increased weight to the significance of their relationship. Upon her resurrection, Adler confesses that despite the fact that she’s a lesbian, she has feelings for Sherlock. Her feelings, in a way, mirror those of Watson, a self-proclaimed straight man who clearly has a deep emotional attachment to Sherlock. Sherlock then forms the apex of a peculiar love triangle at once sexual and cerebral.

|

| “Brainy is the new sexy.” – Irene Adler |

Adler tricks Sherlock into decoding sensitive information on her camera phone. After breaking the code in four seconds that a cryptographer struggled with and eventually gave up on, Adler feeds Sherlock’s ego.

Irene Adler: “I would have you, right here on this desk, until you begged for mercy twice.”

Sherlock Holmes: “I’ve never begged for mercy in my life.”

Irene Adler: “Twice.”

She then follows up on all her sexual attentions toward Sherlock by sending the decrypted code to a terrorist cell. She reveals to Mycroft and Sherlock Holmes that she’d played them both and consulted with Sherlock’s arch enemy Jim Moriarty to do so. It turns out, she was playing a deep game, exerting endless patience in her long con with blackmail as her goal all along. She demands such a sizeable sum for the code to her valuable camera phone that it would “blow a hole in the wealth of the nation.”

At this point, Irene Adler has won. She’s literally and figuratively beaten Sherlock Holmes repeatedly at his games of deduction and intrigue. She’s planned for and obviated every contingency. Adler is the only woman to arouse Sherlock’s sexual and intellectual interest all because she proved to be better than him. Adler masterfully manipulates the emotions of a man who cannot understand how and why people feel, a man who seems incapable of anything but his own selfish pursuits. Her problematic confessions of interest in Sherlock despite her sexual orientation are negated in light of her schemes.

Unfortunately, this is where it all goes to shit.

Just as Mycroft is giving his begrudging praise of Adler’s plot (“the dominatrix who brought a nation to its knees”), Sherlock reveals that he took Adler’s pulse and observed her dilated pupils when interacting with him. He deduces her base sentiment has influenced her into making the passcode more than random, into making it, instead, “the key to her heart.”

|

| Sherlocked…get it? Get it? Snore. |

With that simple, inane phrase, Adler is undone. Sherlock has broken into her hard drive and her heart. Depicting a lesbian character truly falling in love with a man is a complete invalidation of her sexual identity. Not only that, but it has larger implications that are damaging and regressive. It advances the notion that lesbians are a myth, that all women can fall in love with men if given the right circumstances.

Having a female opponent who is more cunning than Sherlock ultimately lose due to her emotions also implies that women are incapable of keeping their emotions in check. Sherlock insists that her “sentiment is a chemical defect found in the losing side.” While he can detach from his emotions, she cannot, and thus he will always be better than her at the so-called game. Not only that, but this emotion versus reason dichotomy further reinforces the destructive gender binary that assigns certain traits to men and others to women, giving privilege to those assigned to men. Even Adler’s seductiveness, her cunning, her manipulation of the Holmes brothers, these characteristics are coded as female. Adler even enlists the aid of the male Jim Moriarty with the implicit reasoning that he is smarter, slicker, and more capable of handling the Holmes brothers.

Irene Adler must make her way in the world as a sex worker who deals in secrets. (Remind you of Miss Scarlet from

Clue at all?)

Capitalizing on sex and thriving on the power dynamics inherent in sex (especially heterosexual sex, in which we know Adler engages) are attributes generally assigned to women even though they are fabrications. Having to engage in sexual activity for money does not give women power. It, instead, forces women to exploit themselves and conform to a regulated form of femininity as well as other people’s sexual desires and fantasies (regardless of what the woman herself wants, likes, or doesn’t like). Considering the appalling number of rapes each year, each day, each hour, we also know that power dynamics (from a hetero standpoint) don’t truly favor women. Though the episode doesn’t get into it, presumably Adler is finally cashing in on all her secrets in order to make a better life for herself, a life in which she does not have to sell her body to survive.

When Sherlock outwits Adler, he forces the dominatrix to beg for her life, which is worth little without her secrets. Though he feigns indifference, he ends up finding her after she’s gone into hiding and been captured by terrorists in Karachi. He then saves her from a beheading and falsifies her death in a completely untraceable way.

|

| It’s poignant that Sherlock holds the sword over Adler’s neck, choosing whether she lives or dies. |

At the end of the episode, Sherlock stands before a window chuckling to himself about how handily he settled the whole scandal with The Woman. He doesn’t only best her at their game of wit, but he debases and de-claws her. Divesting her of all her power, all her secrets, Irene Adler is completely at his mercy and must to be rescued like a damsel in distress or, worse, like a naughty little girl who’s gotten in over her head and must be dug out by her patriarch.

Despite the frequent declaration that “things are better for women now,” it’s hard to ignore that a story written in 1891 created a larger space for a woman to be strong, smart, and to escape. It’s also hard to ignore that Sherlock doesn’t just outwit Adler, he systematically dismantles all her power and only then does he graciously allow her to live. We can wish the last ten minutes of the episode had been cut, allowing for an ending in keeping with the original story, an ending that empowered a woman as one of Sherlock’s most formidable foes. A potentially more fruitful wish would be that Irene Adler returns in future seasons, stronger and more prepared to play the game against Sherlock Holmes, a game we can only hope she will win the next time around.

———-

Amanda Rodriguez is an environmental activist living in Asheville, North Carolina. She holds a BA from Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio and an MFA in fiction writing from Queens University in Charlotte, NC. She writes all about food and drinking games on her blog Booze and Baking. Fun fact: while living in Kyoto, Japan, her house was attacked by monkeys.