|

| Apparently, sexy fireplace dancing and making out with a taxidermied wolf aren’t part of Jules’ normal partying repertoire. |

|

| The non-virgin virgin. Talk about not really fitting into a gender stereotype. |

|

| Bong Boy to the rescue! |

———-

The radical notion that women like good movies

|

| Apparently, sexy fireplace dancing and making out with a taxidermied wolf aren’t part of Jules’ normal partying repertoire. |

|

| The non-virgin virgin. Talk about not really fitting into a gender stereotype. |

|

| Bong Boy to the rescue! |

———-

|

| Alexandra Breckinridge (l) and Frances Conroy (r) as American Horror Story‘s Moira |

“Be it Lilith or Eve, is seen as the enemy of harmony, well ordered life and peace. She is the source of all evils, the originator of sin in the world. This negative understanding of the woman, particularly Eve, is presented in the words of some prominent male scholars. The Jewish commentator, Cassuto, maintains that the serpent too is female and the cunning of the serpent is in reality the cunning of the woman. The German Old Testament scholar, claims that women confront the allurements and mysteries that beset our limited life more directly than men do, and therefore, woman is a temptress. Mckenzie connects woman’s moral weakness with her sexual attraction and holds that the latter ruined both the woman and the man. Thus, male interpreters understand woman as responsible not only for the origin of evil in the world, but makes female “to represent the qualities of materiality, irrationality, carnality and finitude, which debase the manly spirit and drag it down into sin and death.”

|

| The Vampire Lovers | L-R: Carmilla (Ingrid Pitts) and Laura (Pippa Steel) |

Guest post written by Lauren Chance.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that any fandom, genre or medium must be in want of some lesbians and lo, the so-called ‘lesbian vampire’ genre that exists as a subsidiary to the vampire mythology is here to theoretically do what all lesbian sub-genres inevitably exist for. Horror, to speak generally, is created by men for men and vampires, with their sexual connotations and otherness are arguably the finest example of the masculine expression of the dominant male — one that kills as it penetrates and, as Bram Stoker would have it, infects the mind of the innocent, virtuous and above all else, stupid female.

|

| Carmilla (Ingrid Pitt) in The Vampire Lovers |

In both the novella and The Vampire Lovers, Carmilla exclusively stalks female victims, showing little interest in the male characters as anything other than fodder or a means to an end; Ingrid Pitt’s Carmilla never looks quite as comfortable with the lone male in the film she interacts with in a sexual manner as she does with the various women she seduces and bites. As an acting choice it works wonders towards directing a great deal of the interest and sympathy in the film firmly towards Carmilla, rather than the largely inconsequential male lead who is filmed as a somewhat heroic lead but, as with all of the male characters, is filmed as if we should have no reason to be interested in them: there is no doubt that Ingrid Pitt and Carmilla are the stars of this film, regardless of Peter Cushing’s presence.

|

| The Vampire Lovers |

|

| The Vampire Lovers |

There is a softly lit air of concealment to the first scene and a rather more obvious silhouette to the second, however, it would be difficult to argue that though the scenes are sexual in nature, they aren’t presented through the “male gaze.” These women aren’t entering into carnal pleasures that they inexplicably have every knowledge of already and are therefore able to put on a show for the gratification of others; indeed the appreciation of Carmilla is seen in the faces of the female characters and it is with tentative exploration that they approach the mysterious woman.

|

| Mme. Perrodot (Kate O’Mara) in The Vampire Lovers |

**Cross posted from Not Another Wave

Rachel Redfern has an MA in English literature, where she conducted research on modern American literature and film and it’s intersection, however she spends most of her time watching HBO shows, traveling, and blogging and reading about feminism.

|

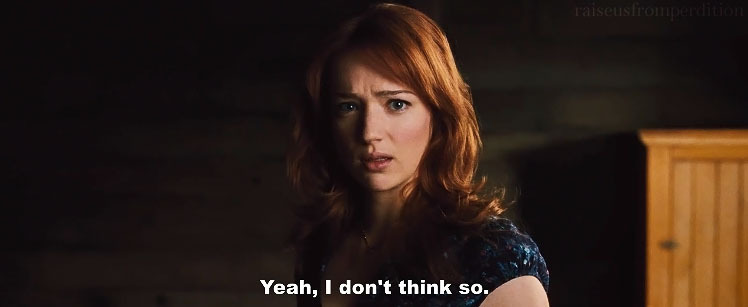

| The lips in the opening sequence–the biting action has sexual and fearful connotations. |

|

| The actors who will appear later as Magenta and Riff Raff play American Gothic in the first scene at the church. |

|

| Riff Raff welcomes Brad and Janet to the castle; the American Gothic painting looms behind him. |

|

| Dr. Frank-N-Furter introduces himself to Brad and Janet. |

|

| Frank-N-Furter, seated, flanked by (from left) Columbia, Magenta and Riff Raff–all of whom he as used for his gain. |

|

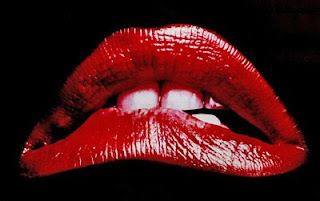

| After a lustful night with Frank-N-Furter, Janet embraces her sexuality with Rocky (she places his hands on her breasts). |

|

| Columbia, Rocky, Janet and Brad have all reawakened in Frank-N-Furter’s gender-bending image for the floor show. |

|

| Frank-N-Furter floats in the pool, meticulously placed above Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam. |

|

| Riff Raff and Magenta appear again as a futuristic American Gothic; his laser pitchfork will kill those whose “lifestyle” is too extreme. |

|

| Not this. |

While one can easily find wider representation in art house movie theaters, commercial, blockbuster films for the masses have long been entrenched in a sexist Hollywood boys’ club. While these commercial films had flaws, the audience support and huge profits should teach Hollywood a lesson about what women want.

|

| Bridesmaids featured a female protagonist and told a uniquely female story, while still attracting and entertaining male audiences. |

|

| Kristen Wiig co-wrote the film. |

|

| Magic Mike proved the female gaze is alive and well. |

|

| Many audience members were disappointed that there wasn’t more stripping. |

|

| Mia Wasikowska and Glenn Close in ‘Albert Nobbs’ |

Haunting and sad, Albert Nobbs tells the tale of a woman who disguises herself as a man in order to survive in 19th Century Ireland. A “labor of love” and a “dream fulfilled,” Oscar nominee Glenn Close, who co-wrote the screenplay, tried to get Albert Nobbs made into a film for 30 years. Adapted from the play, which Close starred in on Broadway in 1982, is itself adapted from George Moore’s short story. Moore’s books were controversial “because of his willingness to tackle such issues as prostitution, extramarital sex and lesbianism.” Rodrigo Garcia’s poignant film Nine Lives, which Close also appeared in, showcasing 9 vignettes of women’s lives, is one of my favorite films. So my expectations were high for Albert Nobbs.

Was this a “jaw-dropping performance” by Glenn Close? She was absolutely outstanding. I didn’t realize at first just how good of a job she did until I realized I completely forgot that it was Glenn Close! I’m used to seeing her play strong, confident or assertive women. Here, Close plays a character shy, awkward, guarded and desperately lonely. She melts into the role. She’s as straight-laced and tightly wound as the prim and proper world around her.

“Albert was particularly tricky because there’s always the question of how much should show on her face because a lot of it is somebody who’s totally shut down, who doesn’t even look people in the eye. Servants weren’t supposed to look people in the eye, but she’s an invisible person in an invisible job. And then her whole evolution is slowly being able to look up – the first time she really looks someone in the face is after she’s told Hubert her story and then she kind of looks out to her dream.”

|

| Janet McTeer and Glenn Close |

“I tried to be, on the one hand, very male, by which I mean large and expansive and confident and sitting on the back of the heels, as it were, and on the other hand I wanted [my character] Hubert to have as many as what we consider to be the loveliest of the female qualities — empathy, compassion, kindness. I wanted Hubert to be a really good mixture of both.”

After Albert meets Hubert, she realizes she could have a life of companionship. SPOILER -> Hubert is married to a woman she adores and a beautiful scene between the two portray a tender, loving and devoted couple. <- END SPOILER Hubert gives Albert hope for a different future: a life free from the shackles and confines of loneliness. In a bittersweet scene, Hubert and Albert walk along the beach together. Albert in a dress, the first she’s worn in 30 years, runs along the beach. Reminded of her old identity, in a rare expression of emotion, she’s unconstricted, buoyed by freedom and sheer joy.

Many movies contain cross-dressing plotlines for comedic effect. But not a lot exist that focus on gender-bending from a dramatic angle. Boys Don’t Cry and Transamerica explore the lives of a trans man and woman while Yentl and The Ballad of Little Jo both echo Albert Nobbs as they feature women who choose to live as men in order to survive or pursue their dreams. An act of violence as a young girl catalyzes Albert to live as a man to protect herself and survive.

Critics have focused on the gender components. But class, an equally important theme, threads throughout the entire film. Albert Nobbs depicts how women contended with and endured poverty. We witness the stark dichotomy between the lavishly wealthy clients and the servile wait staff in the hotel. Servants in the Victorian Era were to be invisible, never looking the upper class in the eye. With her downcast eyes, Albert remains dutiful. Yet she begins to aspire for more. Albert has been saving her money all her life and hopes to open a shop of her own.

The film portrays relationships and courtship as an economic contract. When Albert courts the coquettish Helen (Wasikowska), Helen expects and asks for all sorts of gifts and trinkets. SPOILER -> We also see class play out after Helen gets pregnant. Women needed men in order to survive financially. Women who give birth to children out of wedlock were punished fiscally, fired from their jobs. Husbands provided fiscal security. <- END SPOILER Gender and class coalesce. You realize Helen’s gender and station in life condemn her situation. Albert and Hubert would never be able to attain their dreams (and Hubert her independence) had they retained their identity as women.

I perpetually worry audiences watch period films with dangerously confining gender roles and then sit back thinking, “Phew, we’ve come so far!” Yeah, no, we so haven’t. Albert Nobbs raises so many thought-provoking questions. Why is the male gender the more “desirable” gender in society? What does it say about a society where half its population has a mere two options for their lives? How can women take charge of their own lives amidst confining gender norms? But therein lies my problem with the film. It provides no conclusions, the answers remain elusive.

The tragic story of Albert Nobbs lingered in my memory long after I left the theatre. Its exploration of female friendship, lesbian love, class and poverty, gender roles and a woman’s self-discovery, truly make it a rare gem.

|

| Movie poster for Imagine Me & You (2005), directed by Ol Parker |

Note: the following contains links to TVTropes.com (a black hole time suck), spoilers for Imagine Me & You, and spoilers for several other gay-spectrum movies & television, including…. A Single Man, Bend It Like Beckham, But I’m a Cheerleader!, Friends, Kissing Jessica Stein, Lost and Delirious, Notes on a Scandal, Sunshine Cleaning, and Whip It.

|

| They’re just friends. Very cuddly friends. |

The film realistically introduces the idea that not all women who marry men 1) stay married to them, 2) stay heterosexually identified, and 3) are happy in those marriages. I recently showed the film to a married lesbian couple, one of which had previously been in a relationship with a man. She told me it was refreshing to see that, to see her story reflected on screen. In addition to questioning her sexuality, Rachel also struggles with the expectations of her mother, and then her husband to procreate. Coop brings up the question of whether sex is better after marriage, under the expectation that it continues.

The fact is that real marriage, whether or not one of the parties involved is questioning their sexual orientation, has problems. Through Luce’s profession, we see several people, including Heck, use flowers as a kind of healing balm for the myriad troubles of life. But as Heck discovers, if something actually is wrong, flowers won’t do a damn thing.

Oh, Coop. What a sad figure of arrested development. He’s played for laughs as he continues flirting with a known lesbian who, we know, will never give in to his insisting that he’s great in bed. Perhaps he even grows up a little by the end, realizing that getting involved with married folks isn’t as cut and dry as he hypothesized.

There’s Zoey, too, Luce’s sassy gay friend, there to encourage Luce to get out there and date and to point out the sexual tension between Luce and “Barbie-heterosexual” Rachel. As if we didn’t know already.

8 – Lesbian Panic

Of course, that doesn’t stop the panic by 20th Century Fox, which cites the same-sex romance as “shocking” on the DVD blurb.*

7 – “Older” people have sex and relationships!

6 – Lesbians Are People, Too!

While Imagine Me & You doesn’t do much to challenge the way viewers accept how women look (this, I think, isn’t the story to drive home a point about butch presentation or androgyny), it also avoids coding either female lead as lesbian. When we first meet Luce, she comes across as somewhat non-sexual. Her look is shaggy-casual, but she works as a florist!

The film also comfortably side-steps gender roles with Rachel and Heck. Rachel has a professional writing job. Heck, currently working in finance, longs to be a travel writer. Rachel is the one who cheats. Heck is the one who has an emotional breakdown. (And more about Heck in #4.)

It isn’t easy to identify Rachel or Luce as butch/femme, or even as the “man” or “woman” in the relationship.

5 – Not the End of the World

There is absolutely a time and a place for films and media that explore the times when It Doesn’t Get Better; sometimes it’s nice to see a film where coming out isn’t the end of the world. Part of the reason this works in Imagine Me & You is the relationships built between characters. I’ve been told I’m not supposed to use the Bechdel Test when dealing with lesbian movies (hah!) but I think it’s important to point out that there are several scenes between women in the film, not discussing men or the love interest – regardless of gender. The strength of cross-generation connections is one of the highlights of the film, for me. Luce has a wonderful, nuanced, and open relationship with her mother that is a delight to see on screen. This sort of story can offer hope, amusement, escapism and a relatively non-threatening introduction to lesbians for the uninitiated (in fact, I plan on showing the film to my romantic comedy-loving mom).

While there are times when Heck’s actions and motivations slip dangerously close to that of the Nice Guy(TM), he consistently knows better and when he is behaving like an ass, he takes steps to correct it. After all, Heck is the kind of guy who dances with kids at his wedding, who stands up to his “arse” of a boss, who seems happiest when his wife is taking charge, and who — in a moment I know I connected with — is afraid to ask Rachel if something is wrong because, what if it is?

|

| The suggestion is there, if you look for it, that the hetero-romantic comedy wedding finale isn’t the happily ever after those films would have you believe. |

3 – The Stars

Taking a moment to be shallow if I may: Imagine Me & You is a really pretty film. The direction is simple, but filled with clear lines and sharp colors. And the stars aren’t bad to look at either. The supporting cast features British staple Celia Imrie (random fact: she played the first female fighter pilot in a Star Wars film!) and familiar face Anthony Head (Giles on Buffy the Vampire Slayer). Matthew Goode, who plays Heck, is no stranger to gay film, having played the dead boyfriend in A Single Man, and the not-naked dude in Watchmen (:cough:).

Then there are the leads. Piper Perabo (Coyote Ugly, Lost and Delirious, Covert Affairs) and Lena Headey (Game of Thrones, Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles). Maybe it’s just me, but those acting credits speak for themselves.

2 & 1 – NO ONE DIES, ATTEMPTS MURDER OR SUICIDE, OR IS THREATENED OR THREATENING

So yeah. There’s that.

*I took a quick look at the other films 20th Century Fox imprint Fox Searchlight has to offer and found what might be a coincidence, but also looks a little suspicious. Of the women-centric/lesbian-oriented films under the Fox Searchlight banner, almost all were problematic:

This is hardly definitive research, but it makes me think harder about Imagine Me & You‘s final scenes. The implication is that Coop and Heck both have sexual happy endings (a child, an in-flight romance) while Rachel and Luce don’t even get to finish the movie with a kiss.

The film is also rated R by the MPAA, something I question because two “fucks,” a few “arses,” and zero nudity hardly adds up to something I wouldn’t allow a 17 year old to see. Even with some sexual discussion and two — count ’em, two — lesbian kisses!

———-

|

| Movie poster for Kissing Jessica Stein |

(Warning: Contains spoilers about Kissing Jessica Stein.)

Though words like “bisexual” and “queer” are never used, Kissing Jessica Stein is about sexual fluidity. The Rilke quotation mentioned throughout the film makes this theme obvious:

“It is not inertia alone that is responsible for human relationships repeating themselves from case to case, indescribably monotonous and unrenewed: it is shyness before any sort of new, unforeseeable experience with which one does not think oneself able to cope. But only someone who is ready for everything, who excludes nothing, not even the most enigmatical will live the relation to another as something alive.” (Emphasis added)

Much like Alyssa in Chasing Amy, Helen places a personal ad in the Women-Seeking-Women section because she “excludes nothing” sexually. When it occurs to her that, in all her sexually adventurous years, she has yet to sleep with a woman, she decides to give it a try – hence the personal ad. But she’s completely unprepared for Jessica Stein – who Helen later calls a “Jewish Sandra Dee” – to respond. As the film chronicles the rise and fall of Jessica and Helen’s romantic relationship, it tackles some big questions: Can a woman who’s only dated men have a successful sexual relationship with a woman? When, if ever, is secrecy in a relationship acceptable? Can a relationship with high emotional connection and low sexual compatibility survive?

|

| Jessica and Helen in Kissing Jessica Stein |

Kissing Jessica Stein provides no easy answers to the questions it asks, which I appreciate. The film understands that sexuality is complicated, and not everyone shares the same capacity for fluidity and sexual experimentation. The film also understands that there is no definitive recipe to a successful relationship, because people are different and have radically different priorities when choosing significant others. Jessica and Helen start out coming from similar places – both of them have identified as straight for all of their lives, and both of them want to question that assumption and explore the possibility of dating another woman. In time, they find that they truly are attracted to each other – more than that, they love each other – but that attraction manifests differently in each of them. While Helen has no insecurities about a sexual relationship with Jessica and longs to have the kind of relationship with Jessica that she’s had with men in the past, Jessica is more interested in her emotional connection with Helen than her sexual one. I don’t think this means that Jessica is straight or that she isn’t genuinely attracted to Helen – we never see her in a relationship with a man, so it’s likely that her sex drive is naturally low. Rather than judging Jessica and Helen for their differences, the film shows both women as they are, and it explores the ways in which their differences both cultivate and destroy their relationship.

|

| Jessica and Helen in Kissing Jessica Stein |

When I watch Kissing Jessica Stein now, I’m transported back to a very specific time and place. I remember being sixteen and newly out as bisexual. I remember anxiously anticipating my first kiss from another girl. I remember starting to understand that sexual expression can be flexible and doesn’t have to conform to societal norms. It shouldn’t matter whom we love or what we call ourselves – only that we love at all, and that we express that love in the most honest way we can. Kissing Jessica Stein is not the first film to convey this message, nor does it do it as well as some other films. It’s certainly not as risky as Shortbus, or even Humpday. But it captures a feeling to which many can relate. And even when it fails, it feels far more believable than most comedies of its genre.

When it comes to GLBT representation in the media, unless a television show is targeted specifically at the community, erasure continues to be the norm. Urban fantasy has moved from a small die hard audience to the mainstream and though we can regularly see shows about vampires, werewolves, fae, and ghosts, there are few GLBT characters and a dearth of decent representation.

HBO’s True Blood and Showcase’s Lost Girl have the most visible GLBT characters on television in North America, in terms of the urban fantasy genre. Though both shows have GLBT characters who have extremely high profiles and a reputation of being extremely GLBT friendly, there are certainly many problematic elements.

True Blood is based on The Southern Vampire Series written by Charlaine Harris. In the novels, Lafayette is killed off quite early and is shamed for participating in a sex party. Thankfully, the character of Lafayette in True Blood has become a staple of the show. Despite being a fan favourite, Lafayette is a character that inarguably fulfills a lot of stereotypes that are aimed at same gender loving men of colour. Lafayette is a cook but he moonlights as a sex worker and a drug dealer. Though he is routinely given some of the best lines to say, he too often falls into the sassy best friend role.

|

| Nelsan Ellis as Lafayette and Kevin Alejandro as Jesus in True Blood |

In season three, we learned that Lafayette only started dealing V and doing sex work to pay for the hospitalisation of his mentally ill mother and though the reason is understandable, no other character on True Blood has been forced into this position though they are all working class.

If Lafayette is dogged by several stereotypes, Talbot revels in them. The lover of Russell Edgington (who is an awesome villain but also personifies the depraved, psychopathic homosexual trope), Talbot is a 700-year-old vampire who squeals at the sight of violence. He throws epic temper tantrums over the interior decorating. Someone stamp a rainbow on him and call his unicorn, he’s done. But to quickly fill his shoes we have Steve Newlin – get yourself another trope bingo card because he’s a) a gay man trying to force his attentions on a straight man b) a closeted homophobe, c) a closeted, bigoted preacher and d) getting campier by the episode – have you hit bingo yet? Bet you will by the end of the season, this was just 2 episodes!

The women aren’t free from stereotyping either; Tara finds her love for women and with it an interest in kick boxing – did she get some free dungerees and power tools with that?

I do have to say that not all the portrayals are stereotyped – Eddie subverts many (albeit he exists to serve and help Jason grow) and Jesus more – we don’t see enough about Pam and Nan to see what they fit. But except for Pam, they all fit one trope – GAY DEATH. Yes, there’s a drastic amount of “gay death” on this show. It’s a sad trope that GBLT people rarely live long on the television screen and their sexualty is often the cause of their deaths – and with Talbot (who actually died during gay sex! And to hurt his gay lover), Jesus (at the hands of his gay lover!), Eddie (found by his killers because he hired a gay prostitute), Sophie Ann and Nan were racking up the body count.

But, perhaps the most glaring flaw in True Blood is how the GBLT romances compare with the straight counterparts. True Blood is not a show that is shy about nudity or sex scenes – it is pretty unusual for episodes to go by without at least someone humping someone wearing very little. Eric, Sookie, Jason, Bill, Sam – we have seen them naked and going at it hammer and tongs. But Lafayette and Jesus? The contrast is blatant – even most of their kisses are in low light conditions. They go to bed wearing multiple layers of clothing (in Louisiana, no less) and their scenes together commonly have them sitting pretty far apart and lacking any real physical (or even emotional) intimacy. The emotional distance is very telling in what should be some of the most poignant scenes between them – when Jesus is grieving over his dead friend, when he is risking his life going into Marne’s shop, when Jesus emerges from that shop injured (Lafayette actually ran to hug Tara while Jesus bleeds); you’d expect some emotional angst here. But throughout season 4, you could have mistaken them for roommates, not lovers. This sanitisation is sadly prevalent with gay and bi male couples in television in general – their sex lives are considered more obscene than their straight counterparts, in need of censorship and “toning down.” True Blood’s straight explicitness makes this extremely blatant – with Lafayette and Jesus and even with Sam and Bill’s “Water in Arkansas” dream sequence (that cuts out just before a kiss). The closest we get to any explicit scenes is with Eric and Talbot – again with low light kissing, no nudity and, of course, saved for straight audiences by including the dreaded gay death.

We contrast that with the lesbian relationships and, if anything, we see a different story. But is this putting them on the same explicit level as the straight relationships or is it an attempt to pander to the straight male gaze? If anything, the scenes between women are more sexualised than between straight couples – not because they’re more explicit, but because they are less personal. Nan Flannigan and Pam both have sex (oral sex that doesn’t smudge their perfect make up, no less) with nameless, characterless women. The only actual relationship we have seen between two women is Tara and Naomi – and again, we saw them make out and have sex almost before we knew Naomi’s name. She appeared in exactly five episodes – and not for much of them at that – and in that time they were either having sex or fighting over Tara’s deception. She has now disappeared. Tara and Naomi’s relationship seemed to exist more to show sex and provide Tara with conflict than to be an actual relationship. All of these sex scenes feel even more gratuitous than the majority of the straight sex scenes because they add precious little to plot, story, development or any relationship – they’re there for the sake of the sex.

|

| Rutina Wesley as Tara Thornton in True Blood |

I love that True Blood goes out of its way to include so many GBLT characters – yet at the same time they make me cringe. Inclusion of many characters is great – but we shouldn’t be able to go through TV Tropes, ticking off the stereotypes, the tropes and the unfortunate prejudiced portrayals.

In Lost Girl, we move from having a GLBT character as a sidekick to the protagonist. Bo is a succubus – a being which takes life force from others through sexual contact. At first she is only interested in taking energy from evil doers because she has absolutely no control over her abilities. When she discovers that she is actually a member of the fae, and not some sinful freak, Bo begins a relationship with Dyson – a male werewolf. Vying for her attention is also the beautiful human doctor Lauren.

Essentially what develops is a love triangle and, as to be expected, it is far from simple. Bo has good chemistry with both Dyson and Lauren and in the end engages in sex with them separately. The problem then becomes a question of who does Bo really belong with. It is clear from the outset that though she cares very deeply for Lauren, her real love is Dyson. Dyson even goes as far as sacrificing the most important thing in his life – his love for her at the end of season one, in order to save Bo’s life. When they do have a break in their relationship, it is because he is temporarily unable to feel passion for her. It is during this period that Bo explores further possibilities with Lauren, which rather makes Lauren look like second choice.

Lauren is heavily attracted to Bo, but she is searching for a cure for her comatose girlfriend Nadia, who has been in stasis for five years. The first time that Lauren and Bo have sex, it is because Lauren has been ordered to do so by The Ash – the leader of the light fae. This amounts to sex through deception. Unfortunately, this isn’t the last time that sex between women happens at the behest of a man, which reads like cheap titillation. In a break from both Lauren and Dyson, Bo briefly dates the dark fae Ryan and he initiates a threesome, but what the camera focuses on is Bo’s interaction with the woman he procured. Clearly this was a sexual performance meant to please the straight male gaze.

|

| The cast of Lost Girl |

One of the most frustrating aspects of same sex love on Lost Girl is its treatment of the relationship between Nadia and Bo. After spending five years looking for cure for Nadia, Lauren is finally successful. However, after Nadia is infected by The Garuda, a few short episodes later, Lauren quickly assents to her desire to die. How are we to believe that Lauren held this faithful love for all of these years and then so quickly agreed that her partner should die? Nadia and Lauren’s feelings for her were determined disposable for the sake of furthering a love story which has clearly already been decided.

Even when Bo learns to control her desire to drain life energy during sex, there are still only two instances of sex between her and Lauren, which pales to the numerous times that Bo engaged in sex with Dyson. Lauren is the fragile human that Bo can potentially hurt, whereas Dyson literally represents everything that is good in terms of protection, strength and healing.

And this is perhaps the cornerstone of GBLT depictions in media in general – and certainly in these shows specifically – GBLT relationships are nearly always depicted as secondary to relationships of straight people. They can be there, but they have to take a back seat to the “real” relationships and depictions. Too often this backseat results in characters that are fraught with tropes and are frequently laden with stereotype after stereotype.

We’re happy, after so much erasure, that we’re actually seeing GBLT inclusion – and these programmes certainly do a lot right – but there’s still a lot dogging these characters.

———-

Paul and Renee blog and review at Fangs for the Fantasy. We’re great lovers of the genre and consume it in all its forms – but as marginalised people we also analyse critically through a social justice lens.

|

| Greta Gerwig as Lola in Lola Versus |

Romantic comedies usually make me want to gouge my eyes out. Now, that doesn’t mean I hate them all. Some of my favorite films are rom-coms. But every now and again, one comes along that entertains rather than enrages me. Following in the footsteps of female-fronted comedies Bridesmaids, Young Adult and Girls (all of which I love), Lola Versus follows a single woman making horrendously bad decisions yet struggling to find her way.

Supporting Lola through her break-up are her best friends supportive Henry (Hamish Linklater, who I will forever think of as Julia Louis-Dreyfuss’ brother on New Adventures of Old Christine) and scene-stealing sarcastic Alice (Zoe Lister Jones, who also co-wrote the script).

|

| Joel Kinnaman and Greta Gerwig in Lola Versus |

As she tries to move on, we witness Lola ask a man to put on a condom and take a pregnancy test. Not only is it great to see aspects of sex and reproduction. It’s refreshing to see a woman exert her sexuality but not be defined by it merely an object for the male gaze.

While it started off promising, I gotta admit, the bulk of Lola Versus pissed me off. I wanted to shout at the screen, “No, Lola!! Don’t sleep with him!” or “Spend more time with your girlfriends!” or “Don’t believe him that he’s clean…whatever the fuck that means…make him wear a fricking condom!!” or “Stop smoking weed with (and being nice to) your ex-fiancé who dumped you!”

By the end of the film, I realized I wasn’t mad at the movie per se. I was pissed at Lola’s bad choices.

But isn’t that life? Isn’t that what people do when they’re dumped? They obsess over their exes, retracing the steps of their relationship, trying to deciper the clues that led to the relationship’s unraveling. They pine for them. They strategize ways to accidentally run into them (or avoid them like the plague). Either way, there’s a lot of strategizing involved. I wanted Lola to be empowered. To stop obsessing over nice but douchey guys who didn’t appreciate her or who weren’t right for her. I wanted her to hang out with her female friends. But the way the plot unfolded rang more realistic and way more uncomfortable.

|

| Greta Gerwig and Hamish Linklater in Lola Versus |

In an interview with Collider, Gerwig shared how the script spoke to her because Lola was such a hot mess:

“Sometime female characters, especially in the genre of something that people consider rom-com, make mistakes in a cute way or they’re a mess in a way that’s palatable. I like that Lola is a real mess. She’s making big mistakes and it’s not just cute. It’s destructive and self-absorbed and not awesome and she has to recover from that. She stands to damage relationships around her. Even as this crappy thing happens to her at the beginning of the movie, she uses that as an excuse to behave badly for the next year of her life. I like movies about women behaving badly, because women behave badly just like men, and we’re not always adorable and cute about it.”

Gerwig is absolutely right. Women in film aren’t usually allowed to be messy or unlikeable. Although that’s slowly changing.

Lola Versus made me uncomfortable because it reminded me of too many of the bad decisions I’ve made in my life. Falling back into sleeping with people I shouldn’t. Agonizing and analyzing every single conversation. Calling an ex, desperately hoping to rekindle that spark. Settling for someone not that great in a vain attempt to fill the gaping void that my partner’s disappearance has left.

I eventually stopped all this time-sucking nonsense. I thought by hanging onto relationships, I was boldly forging ahead seeking my happiness. But that’s not what I was really doing. I was placing my happiness in the hands of others. And so was Lola.

|

| Zoe Lister Jones and Greta Gerwig in Lola Versus |

The movie tackles the topic of single women and aging. As we approach or pass turning 30 (like me!), we contend with societal expectations. Not that turning 30 is some horrible harbinger of doom. Quite the contrary. I’ve been more confident and comfortable in my own skin after turning 30. But it’s still hard to silence the social cues that tell us our lives should fall into place in a certain pattern.

Here’s the thing about Lola Versus. It frustrated me and I rarely laughed out loud. Although the scene where she screams at the party…priceless. But Gerwig mesmerized me and the film enthralled me. It passes the Bechdel Test (yay!!!). And it boasts one of the absolute best endings I’ve ever seen in a film. Ever.

In every romantic comedy, it’s all about two people getting together in the end. Or if it’s really radical — and trust me, I use that term facetiously — they’re already together in the beginning and it’s about the two lovers facing obstacles but ultimately staying together. The only rom-coms I can recall that deviate from this predictable paint by numbers path are Annie Hall, The Break-Up and Kissing Jessica Stein.

I don’t want to spoil the ending. But I will say this. (Aver your eyes if you want to be completely surprised) Lola achieves happiness, something that had eluded her all along. She suffered writers’ block, not being able to silence the voices and noises in her head — ironic since her dissertation was analyzing silence in film — but now she could write again. She became happy with who she was and with her life.

And it had nothing to do with a man.

Now that doesn’t mean she says fuck you to all her relationships. While she knew how to love other people, she didn’t know how to love herself, a lesson most of us need to learn.

Lola talks about Cinderella with her mom (Debra Winger…so glad to see her in more films!). She tells her that she liked Cinderella as a kid but how fairy tales are toxic, teaching girls to wait for a man to sweep them off their feet and give them shoes. Fairy tales set women up for failure. We put these unrealistic expectations on love and romance. Now, I’m not arguing for settling, not by any means. But fairy tales teach girls that when they grow up, they should wait around for men; that they should put romantic relationships before everything else in their life even sacrificing themselves. Lola realizes that she must navigate her own happiness rather than relying on a man or some lofty romantic fairytale.

Too many romantic comedies subject women to stereotypical gender roles. Needy, passive, just out to find a man. Can’t romantic comedies be intelligent? Can’t they highlight the importance of female friendship too?? Yes, yes they can. And Lola Versusdoes.

One of my favorite lines in the film is when Lola says:

|

| Promotional poster for the new reality TV series Push Girls |

A new reality TV show called Push Girls, starring four disabled women in wheelchairs, premiered on the Sundance Channel last night. And it’s gotten glowing reviews.

Angela is a stunning model, Auti is a dancer who is trying for a baby, Tiphany is designing a clothes line and Mia works as a graphic designer.

And all four women are paralyzed from the neck or waist down and are about to shatter widespread notions of what it’s like to spend life in a wheelchair.

“Push Girls”, launching on the Sundance Channel on Monday, chronicles the lives of the ambitious and dynamic quartet in a way that producers say has never before been seen on U.S. television.

“Plenty of people have no idea what it’s like to spend the day in the life of someone with a disability, let alone a spinal cord injury,” said Tiphany Adams, 29, who was paralyzed in a horrific 2000 car accident.

“How do we get in and out of a car? How do we go to the bathroom. How do we go grocery shopping? How do we get in the shower? How do we get dressed? I thought it was a brilliant idea for the world to see that,” she said.

Told without self-pity, “Push Girls” shows the women going about their lives in Los Angeles just like other good-looking females in their 20s, 30s and 40s – flirting, going to nightclubs, in bed with boyfriends, chatting about love lives and searching their souls about the future.

But television is a visual medium, and one point the show makes with breathtaking rapidity is that tragedy can interrupt even the most seemingly charmed life. The other, more important point is that it can be just that — an interruption rather than an off-the-rails ending.

“If I can’t stand up, I’m going to stand out,” says one of the women toward the end of the pilot, and that would appear to be its theme.

Where others might have chosen to follow the overtly emotional, “The Other Side of the Mountain”-type story line of agonizing transition from able-bodied to physically challenged, this show does not. Instead, it chooses women who have been in their chairs for at least 10 years — which shows in the grace and ease with which they operate their chairs and perform tasks that, to the able-bodied, would seem impossible without full mobility.

Let’s say this first: Popular television is bad at lots of things, and one of them is representations of people with disabilities. Even where they’re present – Artie on Glee, or Walter, Jr. on Breaking Bad – they tend to be in isolation. When there’s more than one person in a wheelchair, for instance, like when Jason Street was in rehab on Friday Night Lights, the story is usually about the disability itself.

I sat down to think about the last time I saw television pass a sort of invented variation (not parallel, but similar in intent) on the Bechdel test: two people with disabilities talking in depth about things other than their disabilities. I’m sure it’s happened, but I strained to think of examples.

It’s still a reality show, like many others. It’s still a reality show about people who are way too hot to be representative of the population, and about people who gossip about each other and share more personal details than most of us would. To a degree, it truly does just happen to be a show about people in wheelchairs, and that’s probably the best thing it could be.

The premiere episode tends to lapse into a “You go, girl” mode typical of shallow treatments of disability, with fist-pumping and treacly background music. It’s a tone that subtly demeans, suggesting that simple things like having head shots taken (Ms. Rockwood is trying to restart a modeling career) must be applauded because, golly, for someone in a wheelchair to do anything other than sit there is a triumph.

A little of that may be necessary to hook an audience that has come to expect this treatment whenever a person with a disability turns up on television, but the faster this show sheds that tone and its preoccupation with sex, the more useful it will be. There are numerous other things we’d like to know about these interesting women besides the particulars of their love lives: their finances, their experiences on the job, their journey to get to the confidence level they seem to have achieved, their hopes for new technologies and medical breakthroughs.

Another challenge for “Push Girls” is dispelling the impression that these women are representative. Certain viewers might well look at them and conclude, “Gorgeous, smart, independent; I guess the disabled-Americans problem has been solved, so I can go back to not thinking about it.”

Over dinner in Beverly Hills recently, the sisterhood was palpable. Funny and vibrant, the women were as quick to tease each other over entrée choices as they were to argue over who looks the most beautiful when she wakes up in the morning. The tears flowed just as easily when the conversation turned to what their friendship means, and not just for the women. Even Chelsie’s father, Jon Hill, and Rockwood’s caregiver, Aunty Judy, became misty-eyed a couple of times.

“It was such a turning point for Chelsie to meet them all at one time,” Jon Hill said. “She’s always been a happy kid, but when she met the girls and we left there, she was singing and dancing in the car. Just pumped up. That’s what I needed to see. Even though she wasn’t depressed, it was just finding that right niche so she wouldn’t be sitting at home in the chair. It’s helped me tremendously being around these ladies.”

A more subtle aspect of the show is seeing how others react to the Push Girls: from rudeness to confusion, there are many levels of discomfort on display among the able-bodied people featured. How the women deal with the awkwardness varies within the group, but it’s one of the more moving subtexts. There’s a mixture of duty and fatigue when Angela talks a photographer through the reality of her leg spasms as he puts on an awkward grin, unsure of how to handle the fact that she could, at any moment, “stroke out.”

The series starts off with the women beginning their very L.A.-flavored journeys toward starting (or restarting) their careers, and there’s something captivating in that struggle even beyond the affecting nature of seeing these women work to transcend their disabilities. Despite the leisurely pace of the filming, which lacks a certain amount of dramatic tension, there’s a fiery spirit to Push Girls that cannot be ignored.