|

| Movie poster for The Purge |

Turns out, the best way to see the latest violent horror film is to watch it in a packed theater in Times Square. The audience laughed together, squealed together, shouted at the screen together, and collectively bonded over the most ridiculous features of the movie as well as the more progressive aspects.

As the credits rolled, a young Black woman sitting behind me stood up and yelled, “And the Black dude survives!” I mean, hadn’t we

all been thinking it? We’re so used to filmmakers killing off characters of color, especially in horror films, that watching a Black dude walk into the sun at the end of a movie after saving a bunch of rich white people stood out as a fucking anomaly.

The Purge is certainly problematic, but it surprised me to feel a sense of … hope at the end of it. Could this reversal of the white savior trope start a new trend in filmmaking? And did a film finally punish a Rich White Dude

instead of celebrating his successes at the expense of others? And what would movies even be like if these became the new tenets of onscreen storytelling?

I like to do this thing sometimes where I show up at films with absolutely zero information about them. The Purge looked like a fun movie to try that with, and I’m glad I did it; if I’d known the premise of the movie in advance, I doubt I could’ve talked myself into paying 75 dollars to see it and spending 45 minutes slow-walking 3 blocks to the theater in the most crowded area of Manhattan. Luckily, the plot made itself clear within the first few minutes.

|

| Video footage of the annual Purge |

It takes place in the future, nine years from now in the United States, which boasts a government known as

The New Founders of America (NFA). The New Founders have instituted an annual day of murder and mayhem dubbed The Purge, allowing anyone to roam the streets freely in search of people to violate so that they might purge themselves of their lurking hate and rage. It lasts twelve hours and during that time no emergency services or police officers exist, making it a free-for-all. Not everyone is required to participate, but people are encouraged at least to indicate their support of The Purge by placing a vase of blue baptisias (baptism, get it?) on their front doorstep in a gesture of solidarity. While the family the film focuses on, The Sandins, appears not to necessarily enjoy The Purge or participate in the “festivities,” they support its existence, mainly because the institution of The Purge lowered the once-staggering unemployment rate to 1%, saving the economy and making the annual crime rate almost nonexistent. The main characters see it as a tolerable, necessary evil, and besides—they’re the richest people in their state-of-the-art secured neighborhood; what’s the worst that could happen to

them?

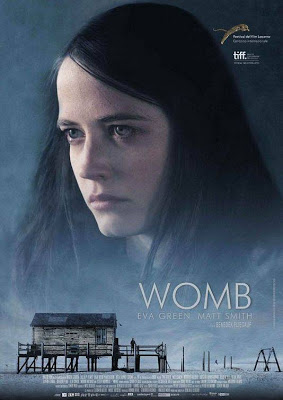

|

| “Don’t forget to put the Baptisias on the porch, Honey!” |

Well, they could help a Black dude avoid getting murdered by a bunch of creepy, self-proclaimed “highly-educated” white people in their twenties, who roam the gated suburbs carrying machine guns and machetes and wearing masks like they just wandered off the set of The Strangers. Your bad, Sandins, your bad.

|

| WTFWTFWTF |

Let me take a step back.

The Sandins actually fucking suck for the most part, at least in the beginning. Ethan Hawke plays James Sandin, who works as a security developer and who clearly profits off the The Purge; the Sandins own the biggest house in their subdivision—a jealous woman neighbor sarcastically “jokes” that The Purge Survival Systems that James sold to everyone in the hood obviously paid for the new addition to the Sandins’ home—and James himself gloats during that night’s family dinner about his rise to the spot of Top Seller at his security firm. (Rich White Dudes profiting off the hardships of others …

does that sound familiar to anyone?) Mary Sandin (Lena Headey) gives the impression she’s a homemaker; we see her cooking dinner and chiding her children (Zoey, a high schooler and Charlie, a younger teen) as she readies them for the pre-purge lockdown, and she leaves the house only to place the baptisias on the porch and speak with the neighbor who envies her family’s wealth. The Sandins seem truly clueless about the extreme jealousy all the less rich white people (minus the token, light-skinned woman of color) feel toward them, but the audience gets the message all over the place: Sandins, consider yourselves fucked.

|

| Uh-Oh |

On the surface,

The Purge aims to critique the sick shit going on in our country right now, albeit very problematically. Dan Gainor, VP of Business and Culture at the Media Research Institute called

The Purge “an obvious attack on the Tea Party and Christians” and

also argued that:

… the movie is a direct attack on the NRA, an organization filled with millions of law-abiding gun owners. The loony left’s reflexive hatred of the 2nd Amendment is founded in the concept that people who don’t break the law are somehow evil for exercising the Constitutional rights.

Okay, Dan Gainor.

The truth? No anti-Christian or even anti-gun message exists in

The Purge, although the director, James Monaco,

has said in interviews that the film does, in fact, allude to an indictment of gun culture. In reality,

The Purge employs extreme gory violence that undercuts any potential critique of violence, and the gruesome knife scenes and weaponless face shattering against tables stick out way more than the gun stuff. At times,

The Purge even seems to support gun ownership; the Sandins wouldn’t have survived those twelve hours without guns, and owning a gun for the protection of oneself and one’s domestic space is a much-touted NRA message. The anti-Christian thing, too, is a reach. The characters worship money for sure, and the film critiques that, but neither Christianity nor any religion ever come up.

Unfortunately, The Purge becomes muddled in its message about government; Big Government runs amok here—an old school conservative’s nightmare—and The New Founders essentially sanction the murder of the have-nots, the people on the lower rungs who can’t afford James Sandin’s security system to cordon themselves off from the annual purgers. If anything, it supports the old school conservative argument against Big Government, and a viewer could easily read it as a cautionary tale for a federal government that holds too much influence over its citizens.

|

| State-of-the-Art-Secured McMansion |

On the other hand, neo-cons of 2013 seem to

think they dislike Big Government while simultaneously

inviting it into wombs all across America, so who the fuck even knows anymore. The point is,

The Purge wants to yell from the rooftops, “How awful for the government to endorse the murder of its citizens!” but ultimately yells, “How awful for the government to endorse the murder of its citizens … but, wait, look how well it works when we rid the country of these homeless welfare seekers!”

The Purge tries to have it both ways and fails to deliver any real cohesive message regarding guns, religion, or the role of government.

But I definitely heard the slam against the one-percenters loud and clear, and what a welcomed fucking change from the endless dumping of

Hollywood Mancession films into the multiplex.

The Purge imagines a science fiction-esque United States where the rich take over entirely and wage a violent war against the lower classes, even going so far as to pass a Constitutional Amendment (the 28th) to require its existence. (Most government officials naturally receive legal protection from harm during The Purge.) Simply put: this futuristic United States decides that murdering those most in need makes more sense than uniting together in support of them. In this way, the film

does seem to offer a critique of the country’s current fringe groups (the Tea Party, most Republicans) by illustrating a worst-case scenario for a society that values capital over people—and fuck if it didn’t scare me a little.

|

| This is the scariest person I’ve ever seen on film |

Because this is a film about class relations and capitalism, the less rich (white people) end up turning on the super rich (white people) during the night—another nod to the idea that unregulated capitalism leads only to societal destruction. The end of the film includes audio of newscasts that play over the credits, with broadcasters reporting that the high number of deaths made that year’s Purge the most successful ever. So, while the film might not necessarily conclude with any real epiphany by the United States and its citizens (yay for killing the homeless!), it allows the audience a glimpse into the lives of a few one-percenters who try to destroy one another, all because of money. Oh, and because Charlie Sandin (a not-yet-sociopathic teen) decides to help a Black dude. “And the Black dude survives!”

As a feminist movie critic, I adored these flips on conventional horror tropes, and several of them exist.

|

| Charlie uses his Robot Baby (omg) to help hide the Black dude from his parents |

The White Savior: The Black dude, who seriously remains nameless, shows up in their neighborhood after the Sandins’ purge lockdown (where a hardcore security system barricades their entire home). Charlie Sandin hears gunfire in the streets and sees in the surveillance cameras the Black dude yelling for help, covering a bleeding wound. Charlie zooms in on the man’s terrified face and decides, “Duh, I need to help this guy.” So he unlocks the security system and yells for the shocked-as-hell Black dude to come inside, much to the dismay of his parents. At first, I thought, “This white savior trope again?!” but it didn’t last long. While Charlie helps the man, the older Sandins clearly want no part of it, especially after a group of asshole college kids (that I will forever refer to as “the highly-educated murderers”) threatens to break into their home if they refuse to release the Black dude back into the streets. See, “that homeless swine” belongs to them, and if they don’t get to kill him, they’re more than willing to kill the entire Sandin clan instead. So, duh, the parents torture the Black dude—in an effort to throw him back to the highly-educated murderers—while Zoey and Charlie freak the fuck out like, “WHAT ARE YOU DOING.”

|

| Charlie watches the Black dude on surveillance cameras |

The Protective Patriarch: All of this occurs in the name of James Sandin protecting his perfect, white nuclear family. He simultaneously apologize-stabs the Black dude several times while saying, “I’m sorry. I need to protect my family.” Mary Sandin, though, gets her, “James, you’re no better than the people out there!” on—because women and children always play the role of Moral Compass when men go astray. That trope unfortunately remains intact for the rest of the film, culminating with Mary’s decision not to murder her new home invaders (the less-rich jealous neighbors, at this point; did we NOT know they were gunning for the Sandins, too?). At one point Mary says, “Too many people have died tonight, so we’re going to end this night in fucking peace.” Or something. Even the Black dude says to James, “You need to protect your family,” offering up himself to the highly-educated murderers, but James experiences a swift change of heart and refuses to sacrifice him. Thanks to the women and children.

And in a way, I liked that the women and children felt compelled to protect the Black dude and not throw him to the wolves/preppies; I didn’t read their desire to do so as an employment of the white savior trope because these highly-educated murderers aimed to roll in there and kill everybody regardless. So the Sandins weren’t saving the Black dude as much as they were making it only slightly more difficult for him to get murdered. “And the Black dude survives!” in the end. And saves (most of) the Sandins. And walks off into the sun. After looking at Mary Sandin and saying, “Good luck” all deadpan. Ha.

|

| Zoey secretly making out with the bro her dad hates |

The Sexual Teenage Girl: Zoey Sandin interests me. Her character follows conventional horror film tropes from the get-go: she dates an older boy, much to the dismay of her disapproving dad because Daddy’s Little Girl. She sneaks around behind her family’s back, and her boyfriend even hides out in her room, staying put for the Sandins’ home lockdown. They make out on her bed while she wears a fucking schoolgirl outfit slash uniform; the scene screams INNOCENT VIRGIN about to HAVE SEX and then DIE because THIS IS A HORROR MOVIE. But. Her dad kills her boyfriend instead in a good ol’ Purge Family Shootout after her boyfriend pulls a gun on James out of nowhere (presumably to purge himself of the rage he feels for not being allowed to date Zoey), and James fires back in self defense. Zoey, a little devastated, runs off and hides for some reason, probably because THIS IS A HORROR MOVIE and groups never stick together.

Eventually, the highly-educated murderers breach the Sandin barricade, and we find Zoey hiding under her bed while—duh again—she sees one of them STOP beside her bed. THIS IS A HORROR MOVIE. While this happens, she overhears another murderer—who’s stroking a photo of Zoey—say, “Exquisite. Save her for me, won’t you?” I immediately thought, please don’t rape her please don’t rape her because THIS IS A HORROR MOVIE, and horror films dole out punishment to their sexually provocative heroines hardcore. But the true highlight of The Purge, for me at least, occurred when Zoey murdered the fuck out of the photo stroker, saving (most of) her family and flipping the Sexual Activity Is Punishable By Death convention on its ass.

|

| Zoey hides under her bed (THIS IS A HORROR MOVIE) |

So, all in all, and as unwieldy as The Purge gets (not unlike this review), I couldn’t help but enjoy most of it. The Rich White Dude gets punished, and the minority characters (including women) survive. That shouldn’t be a progressive movie ending in 2013. It is.