|

| Mindy Kaling as Dr. Mindy Lahiri in The Mindy Project |

|

| Am I mess or a rock star intern? I can’t remember! | Meredith Grey (Ellen Pompeo) in Grey’s Anatomy |

|

|||

| Oh, I get it. It’s butterflies in the…er, ribcage. | Mamie Gummer in Emily Owens, M.D. |

The radical notion that women like good movies

|

| Mindy Kaling as Dr. Mindy Lahiri in The Mindy Project |

|

| Am I mess or a rock star intern? I can’t remember! | Meredith Grey (Ellen Pompeo) in Grey’s Anatomy |

|

|||

| Oh, I get it. It’s butterflies in the…er, ribcage. | Mamie Gummer in Emily Owens, M.D. |

|

| Mindy Kaling as Dr. Mindy Lahiri in The Mindy Project |

|

| Am I mess or a rock star intern? I can’t remember! | Meredith Grey (Ellen Pompeo) in Grey’s Anatomy |

|

|||

| Oh, I get it. It’s butterflies in the…er, ribcage. | Mamie Gummer in Emily Owens, M.D. |

|

| DVD Cover Art for The Last Unicorn |

|

| Various scenes from the film |

|

| The Unicorn in her forest |

|

| L-R: Callie (Katie Parker) and Tricia (Courtney Bell) in Absentia |

|

| The Vampire Lovers | L-R: Carmilla (Ingrid Pitts) and Laura (Pippa Steel) |

Guest post written by Lauren Chance.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that any fandom, genre or medium must be in want of some lesbians and lo, the so-called ‘lesbian vampire’ genre that exists as a subsidiary to the vampire mythology is here to theoretically do what all lesbian sub-genres inevitably exist for. Horror, to speak generally, is created by men for men and vampires, with their sexual connotations and otherness are arguably the finest example of the masculine expression of the dominant male — one that kills as it penetrates and, as Bram Stoker would have it, infects the mind of the innocent, virtuous and above all else, stupid female.

|

| Carmilla (Ingrid Pitt) in The Vampire Lovers |

In both the novella and The Vampire Lovers, Carmilla exclusively stalks female victims, showing little interest in the male characters as anything other than fodder or a means to an end; Ingrid Pitt’s Carmilla never looks quite as comfortable with the lone male in the film she interacts with in a sexual manner as she does with the various women she seduces and bites. As an acting choice it works wonders towards directing a great deal of the interest and sympathy in the film firmly towards Carmilla, rather than the largely inconsequential male lead who is filmed as a somewhat heroic lead but, as with all of the male characters, is filmed as if we should have no reason to be interested in them: there is no doubt that Ingrid Pitt and Carmilla are the stars of this film, regardless of Peter Cushing’s presence.

|

| The Vampire Lovers |

|

| The Vampire Lovers |

There is a softly lit air of concealment to the first scene and a rather more obvious silhouette to the second, however, it would be difficult to argue that though the scenes are sexual in nature, they aren’t presented through the “male gaze.” These women aren’t entering into carnal pleasures that they inexplicably have every knowledge of already and are therefore able to put on a show for the gratification of others; indeed the appreciation of Carmilla is seen in the faces of the female characters and it is with tentative exploration that they approach the mysterious woman.

|

| Mme. Perrodot (Kate O’Mara) in The Vampire Lovers |

|

“What a waste of a perfectly good first act! And what a maddening, nihilistic, infuriating ending!”

“Kind of like what The Shining might be if you took out the ESP. And the ghosts. And the chilling atmosphere. So call it The Sucking.”

|

| Kristin (Liv Tyler) in The Strangers | I spy with my little eye a creepy-as-fuck guy! |

|

| James (Scott Speedman) and Kristin (Liv Tyler) in The Strangers |

|

| The Strangers | “Why are you doing this?” “Because you were home.” |

|

| Kristin (Liv Tyler) in The Strangers |

|

| Kristin (Liv Tyler) in The Strangers |

|

Wes Craven’s 1990s Scream trilogy completely rewrote the slasher genre in a postmodern meta-film. In March 2011, Scream 4 was released, ten years after Scream 3 was originally released, starring the original trio: Neve Campbell, David Arquette, and Courtney Cox-Arquette along with some new teen stars to apparently spur a new trilogy. Yet again, this film rewrites the genre, only this time the film plays with concepts of post-racial, post-feminist girl power by making Ghost Face a white sixteen-year-old girl, Sidney Prescott’s cousin Jill (played by Emma Roberts). Craven portrays Jill as the most violent and aggressive killer of any of the other serial killers in the Scream films. Jill kills mostly other white teenage girls (her best friends), a black police officer who is depicted in a racist fashion, and her own mother. Jill’s vitriolic aggression is fueled by her neoliberal pursuit of media fame and self-consciously performing the role of victim while veiling herself as the white-faced killer draped in a black shroud.

|

|

| Jill Roberts (Emma Roberts) in Scream 4 |

Sidney is constantly stalked by the killer and becomes an attempted target in her house, but she eventually manages to stop him and take refuge in her room. Time passes and characters develop a little more before the final scene during a house party at Sidney’s schoolmate, Stu’s house. The killer attacks the kids at the party, and Sidney is left alive to confront, who she discovers, are two killers: her boyfriend Billy and his friend Stu. They confess to having raped and killed her mother one year before. Gail comes in and briefly deters the two killers from killing Sidney, but in the end Sidney manages to kill both of them, declaring, as her surviving friend Randy comments, “Be careful, they always come back for one last scare,” and just as Billy sits up surprisingly, Sidney shoots him in the head, and she states, “Not in my movie,” claiming the construction of the Final Girl as a place of productive empowerment for girls and violent defense against women-hating men.

|

| Sidney Prescott (Neve Campbell) in Scream 4 |

“Pornography thus engages directly (in pleasurable terms) what horror explores at one remove (in painful terms) and legitimate film at two or more.”

The affect of terror and pleasure, though, seem to also be blurred when thinking about slasher films. Audiences are entertained by the desire to see violence that is unseen. They get a horrific glimpse into the pain inflicted between humans (mostly men killing women), but one productive element of the Scream series presents a productive feminist subversion of these elements of pleasure, pain, humor, and gender. Clover qualifies the commonly found surviving girl at the end of horror films in her essay, “His Body, Himself: Gender in the Slasher Film”:

“The image of a distressed female most likely to linger in memory is the image of the one who did not die: the survivor, or Final Girl.”

And this position of the final girl in horror films is destabilized in Scream 4, as the final girl and masked killer are the same person.

“According to the logic of realism, Scream might well be seen as endorsing violence in the hands of a teen girl. But when viewed in its cinematic context, the film, like the slasher genre in general, provides an opportunity to examine cultural and individual fantasies as they relate to gender and power.”

The girl violence in the Scream films takes a new direction as Jill takes on the role of the killer and enacts violent murders against mostly white teenage girls, a black man, and her own mother in the film, symbolically, hyperbolically constructing post-feminist girl power gone horribly wrong. Jill’s performs a coy demeanor and unassaultive character at the beginning of the film, which is starkly contrasted after her unveiling to Sidney as the killer in the second to last scene of the film. She asserts her position as the “empowered” female remake of Billy as the killer and Sidney as the victim, saying “I don’t want to be like you. I want to become you,” right before she stabs Sidney, thinking she murders her. Jill then proceeds to stab herself, throw herself onto a glass coffee table (evocative of a scene out of Fight Club) as a way to bodily victimize herself.

“We recognize the Apple computer symbol, I think, as a clever icon for the digitalization of the creation myth [. . . ] The bite now represents the byte of information within a processing memory.”

He discuses the temptation of biting into the forbidden fruit, which Eve does despite the prohibitions offered by God to her and Adam in Eden. Halberstam relates this Biblical story to the marketing of Apple products with the bitten apple logo on Apple products representing a capitalist seduction of consumer technology and information. Craven takes this concept one step further by having most every character in Scream 4 tote around some Apple product. The Ghost Face killer calls different characters on their iPhones before each murder. The killers use Apple technology to facilitate and capture the murders on film by using webcams to record each murder and post them onto their blog, reconstructing a do-it-yourself remake of the first Scream film within the sequel. The placement of Apple products throughout the film could be read as a synergistic business pursuit by the film makers, and in some ways, people probably were influenced to purchase a new iPhone after seeing this movie. The film also skillfully challenges the obsessive (mis)use of technology, and the Apple products, to use Halberstam’s analysis, symbolize capitalist seduction and female exploitation through violent murders. In “The Scream Trilogy: “Hyperpostmodernism” and the Late Nineties Teen Slasher” by Valerie Wee, she deconstructs the hyperpostmodernism in the Scream films:

“This shift to hyperpostmodernism was motivated by several factors: (1) the development of new media technologies such as cable, video, and an increasing range of digital media; (2) the emergence of a new teen demographic in the United States; and (3) the entertainment industries escalating commitment to cross-media promotional and marketing practices.”

As Wee argues, the Scream franchise’s insistence on including new media, promotion, and adjusting to the “emergence of a new teen demographic” applies perfectly to Scream 4’s hyperpostmodernism as a next step in the evolution of the series.

|

| L-R: Jill Roberts (Emma Roberts) and Kirby Reed (Hayden Panettiere) in Scream 4 |

The teenage girls in Scream 4 are constantly on their iPhones in the film and are connected to Ghost Face through their phones. In the first scene of the film, there is a comment made that there is now a Ghost Face app. for the iPhones so anyone can replicate the killer’s voice as a prank call to friends. Female bodies become fused with technology: they become as fused with it as it is their source of survival and simultaneously the killer’s invasion into their white middle-class spaces. Halberstam writes:

“The female cyborg, furthermore, exploits a traditionally masculine fear of the deceptiveness of appearances and calls into question the boundaries of human, animal, and machine precisely where they are most vulnerable — at the site of the female body.”

Laurie Strode (Jaime Lee Curtis) in Halloween

Nancy Thompson (Heather Langenkamp) in Nightmare on Elm Street

Suzy Banyon (Jessica Harper) in Suspiria

Selena (Naomie Harris) in 28 Days Later

|

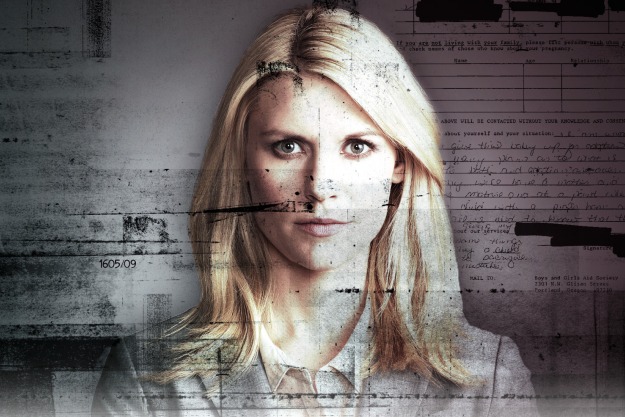

| Carrie Mathison, a haunted yet brilliant CIA analyst. |

“I hate straight singing. I have to change a tune to my own way of doing it. That’s all I know.”

— Billie Holiday

“So while it is true that jazz is a demanding and competitive field for both men and women, it is also true that a woman who shows up for an audition or jam session with a tenor sax or trumpet in her gig bag is greeted with a special variety of raised eyebrows, curiosity and skepticism. Is she serious? Can she play? Time-worn questions about women and jazz buzz through the room before she blows a note.”

|

| Carrie’s personal and professional lives weave together–the professional trumps the personal, but her private battles threaten her career. |

|

| Saul serves as a mentor to Carrie. (Patinkin has been outspoken about issues of television and feminism.) |

“It’s ill-becoming for an old broad to sing about how bad she wants it. But occasionally we do.”

— Lena Horne

“Jazz is not just music, it’s a way of life, it’s a way of being, a way of thinking. . . . the new inventive phrases we make up to describe things — all that to me is jazz just as much as the music we play.”— Nina Simone

“Monk was hospitalised at various points in his career due to an unspecified mental illness and there has been some debate about whether he could have had a schizophrenic or bipolar disorder. (In fact, jazz and schizophrenia have long been linked. It is argued that New Orleans cornetist Buddy Bolden, the ‘inventor of jazz’, improvised the music he played as his schizophrenia did not allow him to read music, evolving ragtime into a more free form of music in the process.) It is an association that positions Carrie, who takes anti-psychotics, as a ‘crazy genius’ like Monk.”

|

| Nick Brody and Carrie develop a complicated relationship, although her theories of his terrorist involvement were correct. |

“When I was a girl, my friends and I used to play chicken with the train on the tracks near our house and no one could ever beat me, not even the boys.”

“One day a whole damn song fell into place in my head.”— Billie Holiday

|

| Carrie chooses to undergo ECT, as she convinces herself in Season 1 that her suspicions about Brody are delusions. |

“Carrie does not suffer from the common female need-to-please trait and, in fact, insists she is usually right. She is impulsive in a job that rewards patience and lies to the few people who can tolerate her…You root for her because those very despicable qualities also make her extraordinarily good at her mission. Danes breathes life and realism into a character who, for once, goes against the clichés of what a female CIA officer is supposed to do and look like.”

|

| Carrie is back in action in Season 2, and Saul is listening. |

———-

|

| Julie Andrews as Mary Poppins |

|

| Mrs. Winifred Banks (Glynis Johns) |

“We’re clearly soldiers in petticoats,Dauntless crusaders for women’s votes!Though we adore men individually,We agree that as a group they’re rather stupid.Cast off the shackles of yesterday!Shoulder to shoulder into the fray!Our daughters’ daughters will adore usAnd they’ll sing in grateful chorus,“Well done, Sister Suffragette!”

Interestingly, this bastion of film feminism occurred accidentally. Glynis Johns thought she was the one getting the role of Mary Poppins, not Julie Andrews. In order to assuage her potential furor over this fuck-up, Walt Disney told Johns that she had a phenomenal solo. To cover his ass, Disney called up songwriters Robert B. and Richard M. Sherman and said (while Johns was in earshot) that she couldn’t wait to hear the song. The Sherman Brothers quickly researched women’s movements in 1910 England, and wrote “Sister Suffragette” so Johns could hear the song after her lunch with Disney.

“In six minutes of film time, Mrs. Banks is changed from a balls-out feminist — ‘No more the meek and mild subservients, we!’ — to a surrendered wife. ‘I’m sorry, dear,’ she says. ‘I’ll try to do better next time.’”

Some have criticized and admonished her as a mother for neglecting her children in order to attend meetings and protests. I call bullshit. Yes, she’s flighty. But I say her advocacy bolsters her motherhood. She continues to advocate for women’s rights, trying to make the world a more equitable place for her daughter and son.

|

| Julie Andrews as Mary Poppins |

Even in the end, when she’s about to leave with the changing wind, her talking umbrella complains that the children never even said goodbye. While she clearly cares for Jane and Michael and her parting is bittersweet, Mary Poppins seems content. She’s finished her job and now she can go. Is that the lesson here? That we should sacrifice our own desire and always serve others? That goals other than family and home are detrimental to personal growth and happiness?

|

| Jane Banks, Mary Poppins, Michael Banks |

|

| The Banks Family |

But I never saw it this way.

In the beginning of the film, Winifred gives out various sashes to Ellen the maid, Mrs. Brill the cook and Katie Nana. So clearly she possessed extras. Why assume she was automatically giving up feminist activism? Since George abhorred suffrage, I saw Winifred’s public display of her sash as a union of the personal and the political. She was bringing feminism into her family rather than merely advocating for equality politically. She was no longer hiding her identity. Finally, Winifred let her feminist flag fly. Literally.

This is a guest review by Jessica Freeman-Slade.

The 1968 movie is legendary, almost impossible to remake due to Streisand’s unforgettable turn (recreating her role from the 1964 stage musical), and with music by Jule Styne and lyrics by Bob Merrill. It’s based on the true story of 1920s entertainer Fanny Brice, one of the major attractions in the golden age of Florenz Ziegfeld’s Follies. Fanny knows she’s a star, but is constantly told that her unconventional looks will keep her off the stage (or as her neighbor puts it, “If a girl’s incidentals/are no bigger than two lentils/then to me it doesn’t spell success.”) But Fanny stands out, because she’s hilariously funny and has a golden voice, and so fame, like anyone who watches the movie, finds her irresistible. What the movie has at its core, is a message about female self-confidence, about self-reliance, about how the world reacts to strong women, and how, ultimately it’s all about chutzpah. Which Fanny (and Streisand) has in spades.

Streisand had only appeared in one Broadway show before then, a small but memorable part in I Can Get It for You Wholesale, and she was far from the only candidate to play Fanny. When Jule Styne consulted Steven Sondheim about the development of the show, Sondheim had major qualms about potentially casting a marquee star like Mary Martin. “I don’t want to do the life of Fanny Brice with Mary Martin. She’s not Jewish,” he said. “You need someone ethnic for the part.” And Streisand was ethnic, especially when put up against a bevy of chorus girls that looked like they’d stepped straight out of Beach Blanket Bingo. The other contenders before her included Anne Bancroft, Martin, and Carol Burnett, but Streisand took the ugly duckling premise and turned it on its head every time she sang. (Fanny’s first line to a skeptical producer says it all: “Suppose all you ever had for breakfast was onion rolls. Then one day, in walks… a bagel! You’d say, ‘Ugh, what’s that?’ Until you tried it! That’s my problem—I’m a bagel on a plate full of onion rolls.”) And she stood out among the other Broadway stars at the time, in the same way Fanny did in her day.

Yes, I know. You have to believe that this girl…

…is considered unattractive, uncastable, and undesirable.

The real Brice had big gummy features–a clown’s face. And though Streisand looks gorgeous in every shot, even in Fanny’s pre-fame days (check out those amazing nails), she doesn’t lose her undeniably ethnic look. She stands out, especially when surrounded by all the Aryan thin-nosed beauties of the Ziegfeld follies. And so the premise of Funny Girl, of almost every joke, rests on whether you believe that Fanny, despite her face, earns every drop of success because of her extraordinary talent. Each joke has the same structure: someone throws a derogatory comment Fanny’s way. Fanny volleys, with wit and acid and intelligence. The movie provides a model to every girl out there (no matter how attractive she is) about how to deal with a world that doubts you because of your appearance, because of your difference. When everyone’s a critic, especially in the entertainment industry, and you know you’re something special, they will have to accept you as you are, and fall in love with you for what you bring to the performance. Just watch Fanny’s first performance for a theater, and how she bends the audience to her will:

Then the joke changes—how could a guy as perfect and beautiful as Arnstein fall for a gummy-faced girl like Fanny? Because he knows what the rest of the world doesn’t—that she has a spark, she stands out, and that’s a sign she’s going to be a star. But the movie, as it traces Fanny’s rise to stardom, constantly returns to the presumably unassailable fact that she can’t hold Nick, or anything, in place simply by being female and beautiful. And so the movie becomes a commentary on what an unconventional woman does to keep herself successful in a world that doesn’t immediately recognize her talent.

Fanny, blessedly, has little time for people who insist she behave conventionally. Even when she lands the dream job, as a featured player among the glittering chorines of Ziegfeld’s follies, she balks at behaving like any other starlet. When Ziegfeld (Walter Pidgeon) puts her in the star spot in the closing number, she says, “I can’t Fanny: I can’t sing words like: “I am the beautiful reflection of my love’s affection.” I mean… Well, it’s embarrassing… If I come out opening night…telling the audience how beautiful I am, I’ll be back at [my first job] before the curtain comes down.” When he refuses to do so, Fanny concedes, but finds her own special twist for the number:

Even when Fanny hooks Nick, and even after she gets to sing a ditty about how great it is to be “Sadie, Sadie,” married lady, the story continues to treat Fanny as a liability. When Nick finally starts showing his shortcomings as a card shark, he is too insecure and prideful to ask Fanny to bail him out. He is thrown into prison, and Fanny gets the news just as she’s heading out of the theater for the night. “You still love him, Miss Brice?” the reporters shout. “The name’s Arnstein,” she replies defiantly. This is a woman who refuses to let her critics define her—even if it means putting the joke on her.

What ultimately carries Fanny, and Funny Girl, as one of the greatest musical comedies ever (and makes Fanny one of the best characters, male or female, ever written for Broadway) is that her weapon is always her strength, her self-reliance, that aforementioned chutzpah. Fanny truly believes that she can do or accomplish anything, including saving her own doomed marriage, if someone just gives her the chance. When she and Nick decide to separate after his release from prison, she is utterly heartbroken. But even in that moment, she pulls herself up and delivers a superb performance, looking more beautiful and elegant than ever. And that’s where the message of Funny Girl really sings out: NOTHING is as radiant as self-confidence.

———-

Jessica Freeman-Slade is a writer who has written reviews for The Rumpus, The Millions, The TK Review, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and Specter Magazine, among others. She works at Random House as a cookbook editor, and lives in Morningside Heights.