Welcome to our second installment of Director Spotlight, where we explore the biographies and filmographies of an often overlooked group: women film directors. (We’ve also spotlighted

Allison Anders.)

Kathryn Bigelow is all over the web right now for being the first woman to win an Academy Award for Best Achievement in Directing (not to mention the Oscar for Best Picture, the BAFTA for Best Director and Best Picture, and the DGA for Directing, among dozens of other awards for

The Hurt Locker). Her win is a source of pride and great relief everywhere, though it’s not without its controversy (chiefly because the Academy rewarded a woman interested in portrayals of masculinity).

The 2000 book Feminist Hollywood: from Born in Flames to Point Break, by Christina Lane, contains a section on Bigelow that nicely rebuts critical reaction to her and her films.

Bigelow, who has taken up the traditionally “male” genre of the action film, has been criticized for lacking any new insight into gender politics. Feminist critic Ally Acker contends that Bigelow “adopt[s] the patriarchal values of fun-through-bloodshed and a relishing of violence” creating “nothing more than male clones.” Similarly, more mainstream male critics have echoed David Denby’s remark: “I can’t see that much has been gained now that a woman is free to make the same rotten movie as a man.” These simplistic generalizations do not allow for the nuances in Bigelow’s work, nor do they stop out of essentialist notions about what is possible in the “male category” of action films. I propose that Bigelow’s films rely on a complex relationship between genre and gender, often blending genres or reversing generic expectations, and that they are best understood in the context of her independent origins.

Bigelow had been making films thirty years before being critically lauded for The Hurt Locker; here is a snapshot of her career.

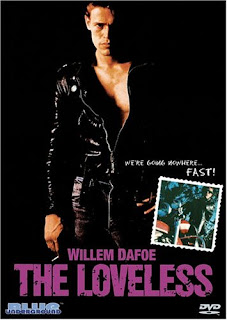

The Loveless (1982)

Bigelow’s feature film debut was also Willem Dafoe’s debut. An homage to

The Wild One,

The Loveless parodied Reagan-style nostalgia for the 1950s. In

a scathing review, Janet Maslin of

The New York Times says:

This movie, a slavish homage to ”The Wild One,” is full of peach and aqua luncheonette scenes, which give it some minuscule visual edge over the original. But otherwise, it’s no improvement. Its evocation of tough- guy glamour is ridiculously stilted. (”This endless blacktop is my sweet eternity,” says the not-very-Brandoesque hero.) And it regards the past with absolutely no perspective or wit.

‘Man, I was what you call ragged… I knew I was gonna hell in a breadbasket’ intones the hero in the great opening moments of The Loveless, and as he zips up and bikes out, it’s clear that this is one of the most original American independents in years: a bike movie which celebrates the ’50s through ’80s eyes.

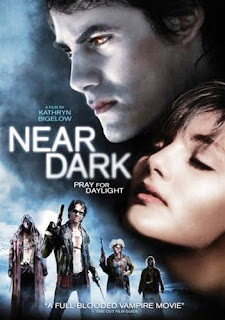

Near Dark (1987)

Fun fact: the above poster was designed to promote the DVD release of

Near Dark, and the

resemblance to a certain tween sensation is no coincidence–from a marketing perspective. The poster may, however, be the only thing these films have in common.

From Maryanne Johanson, The Flick Filosopher:

As darkly amusing as Near Dark is, though, Bigelow never romanticizes one of the great American perils. This is an intense film, an eerie depiction of the isolated, empty middle of America and the dangers that lurk there… and a surprisingly haunting, if never entirely sympathetic, portrait of the loneliness and torment of the eternally undead.

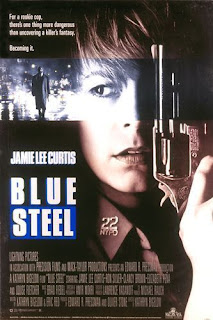

Blue Steel (1989)

Jamie Lee Curtis stars in Blue Steel, a psychologically intense cop thriller. IMDb describes it simply: “A female rookie in the police force engages in a cat and mouse game with a pistol wielding psychopath who becomes obsessed with her.”

Roger Ebert, in his review from 1990, says:

“Blue Steel” was directed by Kathryn Bigelow, whose previous credit was the well-regarded “Near Dark.” Does that make it a fundamentally different picture than if it had been directed by a man? Perhaps, in a way. The female “victim” is never helpless here, although she is set up in all the usual ways ordained by male-oriented thrillers. She can fight back with her intelligence, her police training and her physical strength. And there is an anger in the way the movie presents the male authorities in the film, who are blinded to the facts by their preconceptions about women in general and female cops in particular.

The bottom line, however, is that “Blue Steel” is an efficient thriller, a movie that pays off with one shock and surprise after another, including a couple of really serpentine twists and a couple of superior examples of the killer-jumping-unexpectedly-from-the-dark scene.

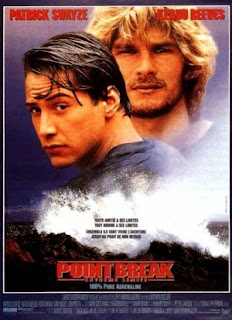

Point Break (1991)

Perhaps her best-known film before

The Hurt Locker,

Point Break is a film about an FBI agent (Keanu Reeves) who goes undercover to find a group of surfing bank robbers. It’s campy, goofy at times, but full of suspense and wonderfully-shot action sequences. As with most of her films, critics were harsh.

It’s hard to decide whether Point Break is a really bad good movie or a really good bad movie. On one hand, it boasts thrilling, original action sequences, a tightly woven caper plot, and a cast jam-packed with Hollywood middleweights acting — and surfing — their asses off. On the other hand, it also suffers from terrifying leaps of story logic, a vacuous emotional core, and some of the silliest dialogue ever spoken onscreen. It’s a Hollywood formula movie at its best and worst.

Strange Days (1995)

Written by James Cameron and starring Ralph Fiennes, Angela Bassett, and Juliette Lewis, Strange Days tackles the sci-fi topic of virtual reality.

The IMDb plot summary:

Set in the year 1999 during the last days of the old millennium, the movie tells the story of Lenny Nero, an ex-cop who now deals with data-discs containing recorded memories and emotions. One day he receives a disc which contains the memories of a murderer killing a prostitute. Lenny investigates and is pulled deeper and deeper in a whirl of blackmail, murder and rape. Will he survive and solve the case?

Once again, Mr. Ebert:

“

Strange Days” does three things that will make it a cult film.

It creates a convincing future landscape; it populates it with a hero who comes out of the noir tradition and is flawed and complex rather than simply heroic, and it provides a vocabulary. Look for “tapehead,” “jacking in” and the movie’s spin on “playback” to appear in the vernacular.

At the same time, depending more on mood and character than logic, the movie backs into an ending that is completely implausible.

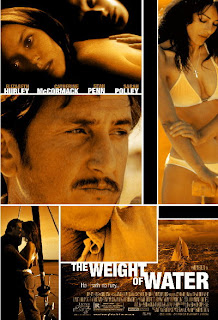

The Weight of Water (2000)

Adapted from Anita Shreve’s novel, The Weight of Water stars Sean Penn, Elizabeth Hurley, Sarah Polley, and Catherine McCormick. Perhaps best known for its two-year release delay (complete in 2000, but not released until 2002), the film received uneven reviews.

Here is the Rotten Tomatoes synopsis:

Two stories unravel simultaneously in this dark and suspenseful film. The first story, set in the present day, concerns a photographer, Jean (Catherine McCormack). She is working on an article for a magazine about a pair of bloody murders that happened 200 years before on the Isle of Shoals, just off the coast of New Hampshire. To get the pictures she needs she must visit the location of the murders, and so her husband, Thomas (Sean Penn), arranges a yachting trip with his brother, Rich (Josh Lucas), and Rich’s girlfriend, Adaline (Elizabeth Hurley). The foursome pal around, enjoying the sea and the sun, while Adaline shamelessly seduces Thomas. Meanwhile, Jean is reliving the Isle of Shoals murders in her head, which is where the second story comes in. Maren (Sarah Polley) is a Norwegian woman who has recently immigrated to America with her husband. When her sister (Katrin Cartlidge) and sister-in-law (Vinessa Shaw) are brutally bludgeoned to death with an axe, she is the sole survivor, and thus the only one who knows the truth about what happened. THE WEIGHT OF WATER draws a parallel between these two tense episodes, as the surf swirls menacingly, foretelling imminent disaster.

Stephanie Zacharek’s review from Salon:

Bigelow’s movie might not come together as cleanly as it should. But as it moves along, there’s always something to watch for, either in the performances or in the way the scenes are so thoughtfully joined. Bigelow is an uneven director — although I find pictures like “Point Break” hugely enjoyable, I couldn’t bring myself to face

“K-19: The Widowmaker.” But in “The Weight of Water,” she’s clearly trying to tell a much different type of story, in a way that at least stretches her capabilities. (Considering the way Hollywood pigeonholes directors, that may have been her chief problem in getting this picture released.) We all complain when filmmakers “sell out” and give us recycled Hollywood formula. But maybe it’s also time to stop listening when we hear those handy, zombielike, all-purpose words, “I hear it’s not very good.”

***

Kathryn Bigelow has directed feature-length films, short films, and television episodes which aren’t included here. She isn’t afraid to take risks in filmmaking, and this trait alone insures we’ll see more work from her in the future.

A last word from Christina Lane:

By rewinding and fast-forwarding through Bigelow’s films–and thereby refusing to adhere to the counter-cinema/Hollywood divide–we can begin to locate her complication of genre conventions and her re-casting of the politics of gender and sexuality. While there is no need to label Bigelow’s films “feminist” per se, they certainly move within a “feminist orbit” and engage political issues. Her films encourage spectators to ask questions about gender, genre, and power.