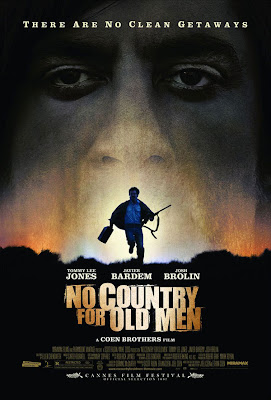

In the entire film, one woman appears–and she’s a wife and mother. She doesn’t have any conversations with other women about things other than men. The film is a Bechdel fail.

In the entire film, one woman appears–and she’s a wife and mother. She doesn’t have any conversations with other women about things other than men. The film is a Bechdel fail.

Okay, I’ve only seen one of the other nominees, but I’m pretty sure about this: Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker is the film of the year. She is the director of the year.

Anyone reading this post is probably familiar with the movie, at the very least for the narrative of its director’s sex and, unfortunately, her relationship with another nominee in the same category. I want a woman to win the award for directing; in the history of the Academy Awards, only three women before Bigelow have ever been nominated (Lina Wertmüller for Seven Beauties, Jane Campion for The Piano, and Sofia Coppola for Lost in Translation). While I don’t want to lose focus on the how good the movie actually is by focusing exclusively on Bigelow’s sex, a few things need to be said.

War is a subject typically dominated by male voices. The Hurt Locker was written by a man. Its protagonists are men. But to make the mistake that war is a male subject is to make a classic sexist assumption. War is a universal subject. One need not be a man to create art about war, or to study texts of war (movies, books, paintings, etc.). In her Salon review, Stephanie Zacharek may put Bigelow’s accomplishment best:

She’s sympathetic toward her characters without coddling them or infantilizing them. Bigelow is an outsider looking in and she knows it, but that status also allows her some freedom. The guys in “The Hurt Locker” are human beings first and men second. The point, maybe, is that you don’t have to have a dick to understand what they’re going through.

We are all implicated in war. If women seem less likely to focus on war, our silence is implicated.

Do I want to see a female director lauded for a woman-centered film? Without question. But Kathryn Bigelow shouldn’t be blamed for making the kinds of movies she’s made for two decades. I didn’t see a woman-centered movie this year that was as powerful and well-made as this movie. And that is a problem.

In The Hurt Locker we have a close and careful character study of three men and their approaches to dealing with combat and their jobs on an elite IED diffusing team at the height of the war in Iraq. Sanborn (played by Anthony Mackie) is a rules man, relying on procedure to maintain his cool. William James (in an Oscar-nominated performance by Jeremy Renner) is the risk-taker, the cowboy figure we want to be the all-powerful hero, but who we quickly come to see is more than a little bit undone. Eldridge (Brian Geraghty) seems to be the youngest and least experienced member of the team; he’s terrified, skeptical, and, ultimately, the most likely to survive post-combat. At times the filmmaking is claustrophobic; we see the world as they see it–as they’ve been trained to see it. Every Iraqi is a potential enemy; even a child.

The Hurt Locker is a powerful anti-war film, which can almost get lost in the breathless action sequences. Its message is subtle but unmistakable: war utterly breaks you. The final scene of the film, which has been criticized for its ambiguity (we see James voluntarily back in action after a brief return home and a too-familiar scene representing shallow American excess), is actually a haunting, almost terrifying reminder of our implication in war. If you see James as a hero at the end of the movie, you haven’t understood a frame of the film you just watched. Yet the film teases us with a traditional genre representation of the hero. We want him to be a hero, only finding joy in the adrenaline rush of war, but he isn’t. He’s an empty shell of a person, nothing more than an animated suit heading toward…nothing. He’s walking off into the abyss. War has ripped out his humanity. This is what we do to our soldiers: we ask them to do the impossible in combat, and it destroys them.