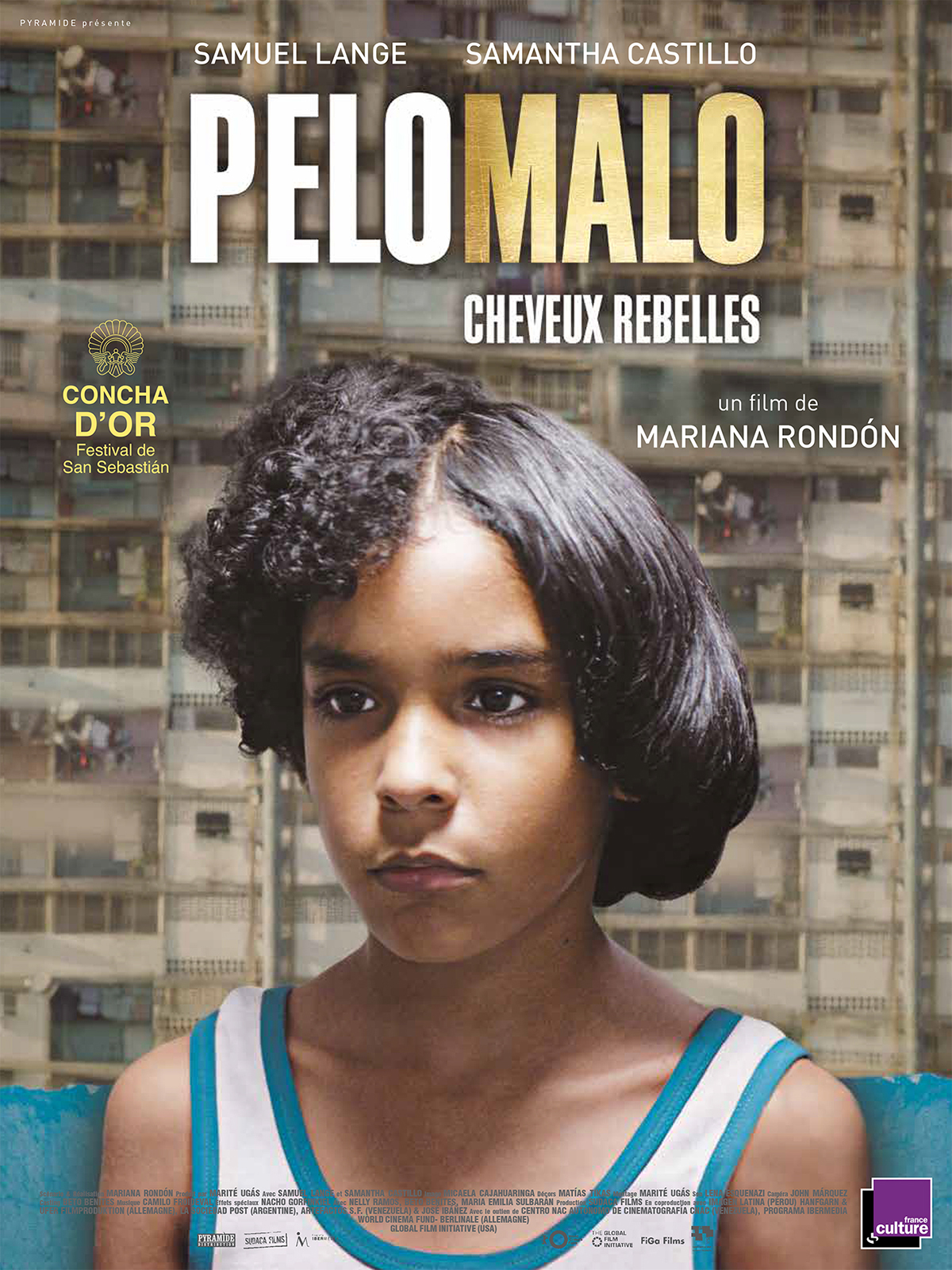

There is nothing more purifying to the human psyche than when another human being sees you for who you really are and accepts you just as you are. And there’s nothing more soul-crushing than when they don’t. This is at the heart of writer/director Mariana Rondón’s Pelo Malo as it follows the journey of a young Venezuelan boy named Junior (Samuel Lange Zambrano).

Junior is a 9-year-old boy living with his single mother, Marta (Samantha Castillo), and infant brother in a Caracas housing development that looks like an overpopulated urban nightmare. I will call the child Black despite differing racial categories between North America and South America. Every coded Black person on the planet knows who the term “Bad Hair” was created for—persons of African descent with that extra curl in their DNA. Most descendants of enslaved Africans shipped to different parts of the “New World” are a mixture of African, Indigenous (Native), and European heritage. Hair textures will fall anywhere from straight, wavy, to extra thick and tightly curled. Or a mixture of all three.

White and non-Black people can have a “bad hair day.” But only Black folks get labeled with bad hair for life, no matter how it is groomed. Especially Black women. Go to any retail store that sells hair products and the ethnic section (read:Black) has more hair creams, gels, mousse, sprays, relaxers, grease, puddings, pomades, hair butter, oils, lotions, to fry, dye and lay that bushy crown to the side. I won’t even get into the hot combs, wigs, weaves, lacefronts, extensions, and clip-ons used to hide a Black woman’s natural hair state. It’s one thing when little Black girls are indoctrinated early to hate their hair, but what about little Black boys who may also be genderqueer? How is this hair struggle tolerated by a homophobic mother struggling to keep her head above water?

Most Black boys don’t have hair issues because they are typically shorn of their locks at an early age. I’ve often witnessed Black mothers and fathers letting their son’s hair grow freely while it is still soft baby hair, but the moment it kinks up a little too tight, they cut it off. As long as boys and men keep the scalp lined up right by the barber, and don’t let it get too overgrown and unkempt, the struggle is minimal. Some Black men (and boys) get “texturizers” (basically light relaxers for men), or sport a wave cap overnight to create spiral waves around their scalp. Back in the day it was the Jheri curl or the California curl, where often dark-skinned men suffered chemical treatments like women to get that glossy-curly look that some lighter-skinned men naturally had. Ironically, to me at least, Junior has the silky dream hair that some Black boys and girls in my part of the world would pray for. The boy is naturally beautiful; however, in his mind he knows that the ultimate beauty is straight, European-looking hair. Famous singers who he likes are his role models. They have straight hair. All his little heart desires in the movie is to take a yearbook picture for the new school year with straight hair. Dassit.

The antagonism stems from his mother Marta, who sees Junior’s fixation with his hair as a huge problem. Not only does her son fuss over his hair and appearance, but he is also effeminate. This is the most painful part of watching Pelo Malo. Marta is a beautiful woman, but her face takes on such ugliness every time she looks at Junior. This child loves his mother to death, spends a lot of time just staring at her, as if trying to figure out the laws of feminine allure. One day Junior sits on a couch watching TV with Marta. He looks over and gazes at her face with such adoration and deep love, but then she snaps on him, “Stop staring at me like that!” From her tone we know he does this often. And we get to witness this longing gaze many times. Marta spends most of her screen time projecting onto Junior her fears of having a gay son. She does some pretty damaging things to try and fix him too throughout the film.

Junior doesn’t break dance like the neighborhood kids, he does a trance-like inner groove with his eyes closed and she is disturbed by it. When she catches him doing this same dance on a city bus, she snatches him up, and Junior doesn’t understand why she is angry. It is literally painful to watch. She piles on the psychological and verbal child abuse. The more that Junior tries to get Marta to love him, she pushes him away. If Venus was a boy, she would be Junior. This fact frightens Marta.

Of course, part of Marta’s behavior is rooted in the harsh marginalized environment they live in that punishes perceived deviance. Her son’s burgeoning homosexuality is just one more problem she will have to deal with on top of being poor, single, begging for her underpaid job back, and raising two children, one of which is still nursing from her breasts. Every time she looks at her son, she sees the discrimination, danger, and ridicule they will both have to face against the outside world. But instead of being compassionate, she is angry and perturbed by his mere presence. Her face conveys so much deep-seated hatred for the boy, that at first I thought she was salty with the child because maybe he looked like his father and there was a bad break-up. However, later in the story we find out that she loved the boy’s Black father. Marta’s face softens just talking about him, so the audience has to search for other clues as to her lack of affection towards Junior. She’s constantly pushing/pulling him places, screaming at him outside their bathroom door whenever he locks himself in there to fix his hair in some kind of way that flattens it.

Marta is loving and affectionate with her white-skinned, straight-haired infant son. There is a tender moment where she is topless and bathing the little one. Junior watches (always watching), a sad yearning in his expression. I wondered. Did she ever hold him like that? Kiss him that way? Maybe when his father was alive?

At one point Marta lies on her bed exhausted from her job search, weary from being turned down for security work, something she is trained for. Junior crawls in next to her and tries to comfort her, and she shoves him away. I began to wonder if it was a combination of his non-conforming sexuality and his Blackness that she despised. There are plenty of non-Black women/men who find Black partners and have children, and yet still harbor racial prejudice. There are even Black-with-Black partners that harbor colorism issues regarding light and dark skin tones.

I admit the colorism/affection issue triggered me in this film. I also come from a single parent household where I am the oldest and darkest child, and the sibling I grew up with is fair-skinned, hazel-eyed, and bone-straight dishwater blonde. My mother was auburn-haired and light-skinned, and although she never had issues with my skin-tone, I was young enough to notice how other people (Black, White, Mexican, Asian, etc) reacted when the two of us went places with our mother. My sister was fawned over (her skin, her eyes, her hair), while I was referred to as the reader. Black children (and non-Black children) learn subconsciously (even before they begin to speak) that whiteness and proximity to whiteness is EVERYTHING, and the opposite is viewed as negative.

Throughout Pelo Malo there were uncomfortable re-rememberings of myself looking at myself in the mirror when I was Junior’s age, slathering Vaseline or Blue Magic Hair Grease on my hair, trying to slick all that stuff DOWN. Tame it. Control it. Essentially hide all that made me stand out as the really Black one in the family. So I was all in my feels watching Junior struggle to get that elusive straight hair. It’s not a comfortable experience to watch a film that basically shows you your childhood and how painful it was. I realized I had built up a lot of buffers around my own hair/skin color trauma.

Junior’s only saving grace is his Black paternal Grandmother Carmen (Nelly Ramos). The moment I see Carmen’s teeny-weeny ‘fro, I know this is a woman who embraces her natural beauty. She doesn’t sport a wig, or straighten her locks. She plays music and likes to dance. She even straightens Junior’s hair when he asks just so he can see what it would look like, but she admonishes him to wet it back up before his mother comes to get him. She spots right off what is evident about her grandson. He is not a hard boy. He is concerned with his appearance. He wants to be a singer. He wants straight hair for his yearbook picture. Grandma Carmen obliges by making him a suit that looks like something the singer Prince would wear. This time spent with Carmen is a respite for Junior, but unfortunately the need for Marta’s love and acceptance is so strong, Junior convinces himself that Grandma Carmen is trying to turn him into a girl. The frilly suit he found so delightful stitched from his grandmother’s hand becomes a suit of shame.

In the end, Marta tells Junior he can only stay with her if he cuts off all his curly ringlets. The hair has become a symbol of Black queerness for Marta. It must be vanquished. It’s a devastating blow, and the last shot we have of Junior is a gut-wrencher. He is in his school uniform wearing close-cropped hair. Unsmiling. It is the yearbook photo. But not the one he wanted.

Pelo Malo ends with no issues resolved, and no hints that life will change or be better for Junior. However, there is one ray of hope in the end credits. We get to see what Junior looks like wearing his grandmother’s Prince-like suit. His hair is blow-dried straight and he dances to his grandmother’s favorite song. He looks glorious. And free.

I left the theater thinking, “How many Juniors, male/female/gay/gender-neutral/genderfluid/transgender/non-binary are out there in the world?”

I know there are millions. And we must be vigilant in holding safe spaces for those children to grow, discover, and define themselves on their own terms. Children like Leelah Alcorn, who recently took her own life because she couldn’t be the person she needed to be. That is the lesson of Pelo Malo.

If nothing else, people should see this little gem just to gaze at the beautiful face of actor Samuel Lange Zambrano. The weight of this movie is carried on his thin little shoulders, and he handles it like a pro. He is perfection.

_______________________________

Lisa Bolekaja is a graduate of the Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Writer’s Workshop and a former Film Independent Fellow. She co-hosts a screenwriting podcast called “Hilliard Guess’ Screenwriters Rant Room” and her work has appeared in “Long Hidden: Speculative Fiction from the Margins of History” (Crossed Genres Publishing), “The WisCon Chronicles: Volume 8″ (Aqueduct Press), and the SF/F anthology, “How to Live on Other Planets: A Handbook for Aspiring Aliens” (Upper Rubber Boot Books). Her latest SF story “Three Voices” will be forthcoming in Uncanny Magazine.