Written by Sarah Smyth.

Warning: Contains MAJOR spoilers!

Like many other fans of the hugely popular political and legal drama, The Good Wife, a few months ago, I sat down to watch the latest episode, “Dramatics, Your Honor,” only to be rudely awakened from the state of pure escapism which the show pleasantly induces. Although often clever, complex, and compelling, the show is also a somewhat ridiculous yet highly entertaining romp, with a taste for outlandish storylines and theatrical, scheming characters. In other words, I do not watch the show to get a reflection of or even a reflection on Real Life. Real Life sucks, and The Good Wife allows me, and others I assume, to escape life’s often mundane, tedious, and sometimes downright brutal existence. However, in this episode, Will Gardener (Josh Charles), one of the main characters who also serves as the love interest to the leading character, Alicia Florrick, dies. Taking this extremely personally – how could the writers do this to me? – I took to Twitter to find answers. Here, I came across this letter written by the creators and executive producers of the show. In it, they wrote a rather jarring sentence: “The Good Wife, at its heart, is the ‘Education of Alicia Florrick.’” As I reflected on this statement, I began to wonder to what extent Alicia Florrick needed to learn something and, more worryingly, to what extent this need to learn is highly gendered.

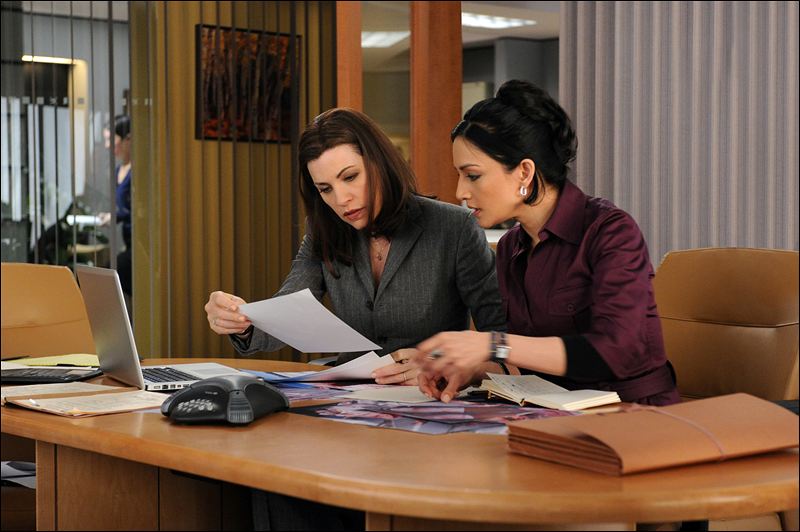

The premise of The Good Wife brilliantly sets up and challenges particular gender roles and expectations. Julianna Margulies plays the lead character, Alicia Florrick. Given Margulies’ age – she was 43 when the show began – and popular culture’s continual privileging of youth, particularly with reference to women, this is an achievement in itself. Alicia’s married to Peter Florrick (Chris Noth, who’s no stranger to playing “bad boy” partners after his role of Mr Big on Sex and the City), who has just been jailed following a string of political and sexual scandals. The pilot sees Alicia dutifully standing by her husband, remaining silent as he apologises for his indiscretions, before the show cuts to several months later as Alicia returns to work as a defence attorney following 13 years as a stay-at-home mom. Through this premise, The Good Wife centralises the conventionally side-lined figure of the wife by giving her a voice and an identity beyond this primary label of “the good wife.” Alicia not only embodies a complex and multifaceted identity as a lawyer, but also as a mother, sister, daughter, friend, and lover. The show also complicates the label of “the good wife” itself. For every character who praises Alicia for standing by her husband, another lambasts her for sticking with him, claiming she fails both herself and women everywhere. The show makes apparent that a woman’s “choice” – for how much autonomy did Alicia really have in this situation? – is intensely scrutinised and criticised. The show then follows Alicia’s struggle with the complexities and obstacles of her identity as she attempts to navigate marriage, motherhood, and the workplace, as well as her increasing sexual attraction for Will, her boss and one of the named partners at the firm where she works.

With a set-up that continually explores and challenges the traditional idea of what is meant for a woman to be “good,” I was puzzled by the idea that Alicia needs an education. As television enters a golden age with shows particularly examining the moral complexities of their lead characters, I wondered whether the need to educate rather than explore Alicia’s character is specifically gendered. As Bitch Flicks examined last year, women are critically neglected from this exploration in two ways. Firstly, women’s contribution is neglected from the critical consensus and canonisation of the television revolution. The title alone from Brett Martin’s book, Difficult Men: Behind the Scenes of a Creative Revolution: From The Sopranos and The Wire to Mad Men and Breaking Bad, makes clear the absence of female-driven television shows within the consideration of this revolution. In The New Yorker, Emily Nassbaum criticises the degradation of “female” and “feminine” culture within the canonisation of television, and proclaims Carrie Bradshaw from Sex and the City as “the unacknowledged first female anti-hero on television.”

This, then, leads me onto my second point. The privilege of exploring a morally ambiguous character is primarily afforded to white, cis-gender, heterosexual, able-bodied men. Female characters, as well as other oppressed groups, in contrast, are refused this privilege. Not only are there fewer critically acclaimed female-driven shows than male-driven shows, and even fewer with Black or queer-identifying leading women. But when there are shows which attempt to explore complex female characters, they face a much harsher moral and critical assessment. For example, whereas the greed, selfishness and pure pigheadedness of Tony Soprano from The Soprano’s and Walter White in Breaking Bad are continually held up as an exploration of character, earning them a cult status within popular culture, Hannah Horvath from Girls is positively reviled (see here, here and here). Although Hannah’s characteristics are less extreme that Tony and Walter’s, she also shares a tendency to be narcissistic, self-absorbed and, at times, unlikeable. Whereas male characters are entitled to be bad, female characters, it seem, must always be good.

Ensuring women remain “good” ensures they also remain passive, docile, and unthreatening. As Carol Dyhouse demonstrates in her book, Girl Trouble: Panic and Progress in the History of Young Women, the lives of young women in comparison to the lives of young men has been plagued with social anxiety and moral panic from the nineteenth century. However, the more I thought about Alicia’s education in The Good Wife, the more I realised that her education is not about being good; it’s about being bad.

Near the end of season one, Alicia makes her first difficult and morally ambiguous decision. As the recession hits, the partners at her law firm, Lockhart & Gardener, must decide which first year associate to lay off, Alicia or Cary Agos (Matt Czuchry). In order to save her job, Alicia pulls in a favour with her husband’s campaign manager, Eli Gold (Alan Cumming), asking him to switch legal representation to her firm, enabling her to bring in top lucrative clients. Not only does Alicia unfairly exploit her advantages, advantages to which Cary simply cannot live up, in order to ensure she secures her positions at the firm. She also uses Peter for her own career prospects, much in the same way that he uses her – Eli continually makes it apparent that Peter’s resurrected career as the States Attorney and, later, as the Governor of Illinois depends on Alicia’s support. Her education in complicating, if not rejecting, her “good” label comes to a head at the end of season four when she accepts Cary’s invitation to start their own firm, pinching Lockhart & Gardner’s top clients along the way.

After Will discovers Alicia’s plans at the beginning of season five, he tells her, “You’re awful, and you don’t even know how awful you are.” As Alicia’s complicated love interest in the show – although at times they engage in brief sexual encounters, Alicia is not “bad” enough to involve herself in a full-blown illicit affair, even if her relationship with Peter is strained at best – Will’s words are highly charged. Nevertheless, there’s some truth to them. Alicia’s come a long way from the relatively meek and unsure character of the pilot. As Joshua Rothman claims, “Everyone, including Alicia, thinks that she’s a victim—but, in fact, she’s a predator, all the more dangerous for being stealthy.” With season six currently airing, the show remains committed to this education. As Alicia considers running for States Attorney, the definition of “good” and “bad” become redefined. The latest episode, “Oppo Research” demonstrates the way in which, within the landscape of politics, what’s defined as “good” and “bad” becomes, simultaneously, much more black and white, and much more tenuous – it all depends on outward appearance and surface. As (politically defined) unpleasant aspects of Alicia’s life are made apparent – although, interestingly, they relate to Alicia’s family members rather than Alicia herself – the show reveals that even good girls have skeletons in their closets.

Without wanting to be prescriptive or wishing the integrity of Alicia’s character away, a significant part of me wants Alicia to fuck up. And I mean, really fuck up. I think this is why I became so invested in the relationship between Will and Alicia, and why I was so saddened by the death of Will. I wanted Alicia to ditch her “Saint Alicia” label and embrace being bad. But the success of female-led shows is not in swapping one side of a dichotomy for another. It’s about embracing a nuanced portrayal of women in television and wider popular culture. The Good Wife succeeds in presenting a character who, despite her best efforts, remains flawed. In this way, Alicia Florrick can finally shed “the good” label for good.

Sarah Smyth is a staff writer at Bitch Flicks who recently finished a Master’s Degree in Critical Theory with an emphasis on gender and film at the University of Sussex, UK. Her dissertation examined the abject male body in cinema, particularly focusing on the spatiality of the anus (yes, really). She’s based now in London, UK and you can follow her on Twitter at @sarahsmyth91.