|

| Arabic movie poster for Where Do We Go Now? |

—

The radical notion that women like good movies

|

| Arabic movie poster for Where Do We Go Now? |

—

|

| The Silence of the Lambs (1991) |

This guest post by elle previously appeared at Shakesville.

“The Help”—the film adaptation of the best-selling novel by Atlanta author Kathryn Stockett—is a feel-good movie for a cowardly [wrt to the ways we deal (or don’t deal) with issues of race] nation.

Despite its title, the film is not so much about the help—the black maids who kept many white Southern homes running before the civil rights movement gave them broader opportunities—as it is about the white women who employed and sometimes terrorized them.

Despite efforts to market the book and the film as a progressive story of triumph over racial injustice, The Help distorts, ignores, and trivializes the experiences of black domestic workers.

I hated, hated, hated that my grandmother and her sister were domestics.

Not because I was ashamed, but because of the way white people treated them and us.

Like… coming to their funerals and sitting on the front row with the immediate family because they had notions of their own importance. “Nanny raised us!” one of my aunt’s “white children” exclaimed, then stood there regally as the family cooed and comforted her.

I’m thinking the maid might’ve been several steps removed from thoughts of love so busy was she slinging suds, pushing a mop, vacuuming the drapes, ironing and starching load after load of laundry. Plus, I know what Mama told us when she, my sister, and I reported on our day over dinner each night and not once did Mama’s love for the [white child for whom she cared] find its way into that conversation: She cleaned up behind, but she did not love those white children.

[Their white employers gave] my grandmother and aunt money, long after they’d retired, not because they didn’t pay taxes for domestic help or because they objected to the fact that our government excluded domestic work from social insurance or because they appreciated the sacrifices my grandmother and her sister made. No, that money was proof that, just as their slaveholding ancestors argued, they took care of their negroes even after retirement!

White male bigots have been terrorizing black people in the South for generations. But the movie relegates Jackson’s white men to the background, never linking any of its affable husbands to such menacing and well-documented behavior. We never see a white male character donning a Klansman’s robe, for example, or making unwanted sexual advances (or worse) toward a black maid.

|

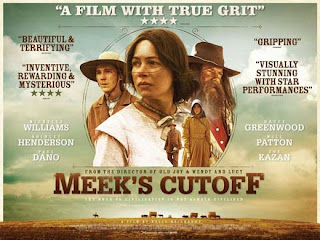

| Meek’s Cutoff (2010) |

The Western genre is traditionally tied up in all kinds of rugged masculinity, and of all film genres, maybe best exemplifies the dominant way the United States collectively imagines itself: sturdy, adventurous, self sufficient, brave, and, well, pretty butch. The problem is, however, that this narrative leaves out a significant number of people, and a significant portion of the story. The Western (and the story of the U.S. West) tries to be the story of the United States itself, and reveals ideology so clearly where it fails–namely, in its depiction of women, indigenous peoples, immigrants, and African-Americans. The genre is, in other words, ripe for retellings and allegory.

If we consider some of our American cinematic “masterpieces,” we often find them absent vibrant female characters, for example (think The Godfather, Citizen Kane, and Chinatown to name just three). As much as I desperately want to see my gender portrayed with respect, honesty, and integrity, many films that deal with the great American mythos don’t have much room for female characters, simply because women haven’t been a part of, and are often still excluded from, the creation story we tell ourselves—a story of brutal boots-on-the-ground capitalism and, negatively speaking, punishing exploitation. It’s a Judeo-Christian story in which the individual male forges his path through the wilderness, an anti-hero who, despite his great wealth and power, can’t overcome his subsequent moral corruption. What’s important to recognize is that the marked absence of “the other” in these films is a comment on an institutionalized patriarchy that extends beyond our everyday interactions to the very heart of our cultural mythos. There Will Be Blood is yet another film that further cements a white male-dominated American story of origin.

|

| Mireille Enos as Sarah Linden in The Killing |

It’s kind of my favorite part of this role — how much of this story is told just through Sarah thinking and letting the audience sit with her in her thoughts.

The female leads are very human and very real and very flawed, yet are good cops. Maybe that’s the difference: women are interested in creating real female leads.

|

| Connie Britton as “Tami Taylor” in Friday Night Lights |

|

| Cast of Friday Night Lights |

(I’d have included pictures, but I defy you to find a picture of any of these women on the Internet that doesn’t put them in some sort of come-hither pose that exposes a whole lot of skin. Sigh. These ladies deserve better.)

One of my favorite characters over the final two seasons of Friday Night Lights is Jess Merriweather. She is the eldest daughter of a former football player-turned-restaurant owner, older sister and surrogate mother to two younger brothers, and football lover. When we first meet her, she is a cheerleader for the new East Dillon Lions (and that image of her remains during the final season’s opening credits); one could wonder why we never saw her as a Dillon Panther cheerleader, but it becomes clear that she probably would never have fit in with the Lyla Garrity-types at the old high school.

No, it becomes clear that Jess is only a cheerleader because it is the only legitimate way for her, a girl, to be close to the game she adores. We see her coaching her younger brother, watching the games not in order to find a potential mate but to dissect plays and increase her football IQ. She is a smart, driven young Black woman, trapped between her love of football and the very gendered expectations of the town. When she is given the opportunity to “coach” star quarterback/boyfriend Vince over the summer, she finds her outlet. Unfortunately, once school and the season start up again, she is relegated to the demeaning role of “rally girl.”

The rally girl is a problematic, but all too realistic, role for Jess. She views herself as Vince’s equal, not his servant. The typical role of the rally girl is to do whatever she can to “motivate” the football players to play at their best on Fridays. In fact, the rally girls wear their respective player’s jersey, essentially owned by the player. It also should be noted that the girls get no say in who their player is; the girls randomly pull jerseys out of a box, and the player can barter and trade girls if the price is right (in one case, it’s a prized pig – do with that what you will). For most of the girls, it is an honor to be a rally girl, to be associated with the “star” football players. But that is not what Jess wants anymore from football; residual fame and greatness is no longer enough.

Jess, instead, becomes the equipment manager for the team. She gets a respectable uniform (versus the scantily-clad cheerleaders), access to the locker room, the coach, the sidelines, and the game. Her job is far from glamorous; she cleans jock straps, washes towels, works to prevent staph infections. Of course, this role strains her relationship with Vince; Vince tries to protect her from the ribbing the team subjects her to, while Jess wants to prove she can hold her own, on her own. In fact, it is Coach Taylor, and not the players, who has the most difficulty accepting Jess in her new role.

Jess fights for the respect of the players and Coach Taylor, working hard to be the best equipment manager/future coach she can be. She presents Coach Taylor with a profile of a female high school football coach to prove to him that it can be done. He tries to scare her by laying out her odds for success. Jess’ confidence never wavers, and Coach Taylor, champion of lost causes (see Vince, as well as Tim Riggins and Matt Saracen), is won over. We last see Jess as an equipment manager at her new school in Dallas.

Jess is just one example of the type of strong, well-developed female characters Friday Night Lights has created. The final two seasons also allowed us to get to know Mindy Riggins: older sister to former cast member Tyra Collette, stripper, mother, and wife to Billy Riggins (who was a former Panther star). In the early seasons, Mindy was simply an excuse for Tyra (and the rest of the cast) to visit The Landing Strip, Dillon’s local strip club. Mindy and their pill-popping, boozy mother Angela, were representative of everything Tyra wished to escape. Tyra did, in fact, successfully make it out, attending UT Austin. But what about those who are left behind in the small town of limited possibilities?

Mindy follows what might be seen as a stereotypical small-town girl path: she gets pregnant and gets married. Both she and Billy struggle with paying their bills and finding meaningful employment. But in what could easily have become a caricature of “white trash” existence (drinking, fighting, divorce, abuse) becomes a very real picture of two people trying to make it work in tough economic times. Mindy also steps up and takes Becky under her wing, a girl in whom she sees much of herself. Mindy also has a boozy mother, an absent father, and is left on her own to navigate through life (but more on her in a moment). When Mindy witnesses Becky being abused by her father and step-mother, she steps in (forcing Billy to do the same) and defends Becky. This is an incredible act from someone who, up until this point, saw Becky as competition rather than a sister. Mindy was perhaps the first person who ever stood up for Becky, acting as the advocate she herself probably never had.

This relationship, of course, is not without its problems; Mindy takes Becky and her son to The Landing Strip and even allows Becky to waitress at the club. Stripping (and as an extension, the strippers themselves) are neither glorified nor vilified by the show. In a town where economic opportunities are limited regardless of gender, these women make money the best way they can, using their bodies to pay the rent. There is nothing glamorous or liberating about their jobs, besides the “easy money” that can be made. But that money isn’t as easy as Becky thinks it is. We see Mindy furiously working out in order to get her body back into shape for the job, and even then, she is relegated to the humiliating “lunch shift.” But the women are also treated with dignity, at least within their group. They are far from being victims or victimized; initially, the show seemed to be saying that Mindy was a stripper because she didn’t have a father and her mother was lacking. But during the last two seasons, the strippers move from being symbols of failure to symbols of survival.

Mindy finds a community with the women of The Landing Strip, and a support system that she never had before, finding a place where she can be honest about her past abortion and how it is still impacting her relationships. The ladies from the strip club also take Becky to participate in one of her pageants; when one of the judges criticizes Becky’s choice of “supporters,” Becky clearly chooses her new family over her dreams of winning pageants. I’ll admit that I bawled like a baby during the final episode when Mindy and Becky say goodbye to each other when Becky moves out to live with her mom again. Family, in this show, is who sticks with us through the hard times.

Which brings us to the issue of the abortion. Becky gets pregnant during the fourth season (by a football player, no less), and she does, indeed, go through with having an abortion (some would argue at her mother’s insistence). Initially, the abortion more immediately impacts another character, Tami Taylor, who was at that time vice-principal at Dillon High School (Becky goes to East Dillon). Tami was brought in to counsel Becky when she had no one else to turn to. But while Becky seems to have come through the abortion okay, we learn in the fifth season that she still carries some unresolved feelings about the boy who got her pregnant.

This portrayal of a young girl feeling trapped by a bad situation is handled, to my mind, sensitively and realistically. Becky is not left unaffected by the procedure, nor does she seem permanently and disastrously scarred. Those around her (her mother, the mother of the baby’s father, the community) seem more upset and emotionally reactionary than Becky herself. It also seems that the extreme reactions of those around her affect her more than the abortion itself; it is again only when she confides in the strippers that she gets the level-headed and unconditional support she needs to move past the event. Abortion, it would seem, is not the issue; the hysteria surrounding it is.

These are just three of the complex women of Friday Night Lights. I’ve focused on the final two seasons, as this is the season that is up for an Emmy. One could look at the evolution of Lyla, Julie, Tyra, and other early-season characters, as well as the myriad of “minor” characters who have populated the edges of the show (Maura the rally girl, Epyk the problem child, Vince’s mother, and Devin the lesbian spring to mind). Each one deserves her own essay, devoted to all the ways the show did (and didn’t) do the characters justice.

|

| Mags Bennett, played by Margo Martindale |

That said, it is a male-centric show, depicting a male-centric world. In the first season, our main character, Deputy U.S. Marshal Raylan Givens (Timothy Olyphant, also nominated for an Emmy), spends his time fighting, shooting, justifying his fighting and shooting to his boss, and protecting and bedding pretty blonds. He also spends an entire episode getting back his cowboy hat. The criminal family he battles is Bo Crowder and his boys, and much is made of the complicated power dynamics between men, particularly fathers and sons. One might get weary from all the testosterone (as the one female marshal acknowledges in an early episode).

But in season two, the show gives us Mags Bennett, head of the Bennett clan, a matriarch wielding absolute power (and a ball-peen hammer) over her territory. She sets herself apart from both the women and the men in the show and their prescribed gender roles, inhabiting both enforcer and nurturer, often at the same time. Margo Martindale, a well-lauded stage actor, too often is relegated to the screen margin, playing the supporting roles of gruff nurse (Mercy), sassy neighbor (The Riches) or kindly old friend (Dexter). Martindale admits in a recent interview that a role like “Mags Bennett comes along maybe just once in a lifetime.” But roles like this—multi-faceted, problematic, and compelling—are what we need to see more of on television.

I don’t know what episode was submitted for the Emmy voters (there are plenty to choose from), but let me make my pitch for the first episode. It doesn’t have the flash of her stirring, but duplicitous, speech to the coal mining company trying to buy the town away from the people, or the shock value of her smashing one son’s hand to bits while blaming the other for her actions, or even the tragedy of the final episode. But it does provide the roundest view of the character, an incredible feat for an initial introduction.

Apple Pie: the symbol of American domesticity, of homegrown goodness, warm and comforting. Mags makes “apple pie” that the entire county admires, but this apple pie is more than it appears to be. It is a symbol of Mags herself. It appears in three distinct scenes, each giving us a glimpse into the complexity of Mags.

Sharing a Slice of History

When she offers it to Raylan, the audience sees it as a peace offering, a moment of communion between two feuding families. As the two recount their shared history, Raylan’s deference to her in the scene is a stark contrast to his interactions with the Crowders. With the Crowders, when Raylan acted with restraint, it was clear that it was out of fear, out of the knowledge that he didn’t hold the power in a given situation. But that didn’t stop him from spouting snarky one-liners. With Mags, Raylan acts not just of out pragmatism, but out of respect. Even as he takes her measure, he addresses her, not as Mags, but as Mrs. Bennett, and is, frankly, polite; it smacks of the Southern gentility that surfaces whenever he interacts with a woman. His gracious acceptance of her apple pie signals to the audience that Mags is a crime-lord of a different sort. When she pulls out the jar, we see her apple pie for what it is: a home-brewed moonshine, and a tasty one at that. But like Mags’ weed, a moonshine named “apple pie” seems innocuous, not the meth or oxycotin that the Crowders dealt.

Pie as Retribution

The apple pie moonshine makes its second appearance in her sit down with McCready (Chris Mulkey), after he has been shot by her boys for stealing and Loretta has made it home safely from her abduction. Again, the moonshine appears to be a communion of sorts, a way for Mags and McCready to admit their sins, ask for each other’s forgiveness, and return to the status quo. And Mags’ speech follows that path, asking after Loretta. She forgives McCready for his stealing, and insists that her son apologize for shooting him and forcing his foot into a trap. Sure, she continues to draw information out of McCready about what he has told the police and what risk he might still pose, but she does so as a benevolent leader. As McCready says all the right things, we watch as both McCready and Mags try to assess the situation and determine what will happen next. Unlike the scene with Raylan, there is no subtle jockeying for power; it is clear that Mags is in control. And it is through her apple pie that she exerts her control. Having poisoned McCready’s glass, she calmly explains to him that his real crime was going outside the family by calling the cops about Loretta’s abductor. She is both terrifying and comforting as she grips his hand as he dies, talking him through the pain and pledging to raise Loretta as her own. She is not a benevolent leader, and her apple pie can longer be seen as innocuous. From this scene on, every time she reaches for a mason jar to pour someone a drink, we question her motives.

Too Young for Pie

Mags and Loretta McCready (the fabulous Kaitlyn Dever) also share a drink in opening scenes of the next episode, and coming on the heels of the apple pie murder, perhaps the audience is supposed to assume that Loretta is a goner too. But, ultimately we know Mags will not kill the girl. Not because she is too kindly or motherly to do so (the season gives us plenty of evidence that Mags can be just as ruthless to her kin as she is to outsiders), but because she longs for something she gave up when she took over the family business. Mags lives in the world of men, and to survive in that world she does what so many strong female characters do—she becomes masculine. Such figures maintain control through fear and violence, they wield weapons and talk of war, and they protect their own at the expense of others. Mags sees Loretta as a possibility for a different way. Having lost her feminine side so long ago, she mistakenly equates femininity with innocence, and struggles to keep Loretta away from the ugly truths.

The audience gets the first glimpse of Mags in this light in “The Moonshine War,” after Loretta comes to see her to atone for her father’s theft. Mags shows real concern for the girl and promises to protect her from the pervert who has accosted her. But she seems even more worried with how Loretta is managing at home, asking her about her father’s ability to take care of her. Mags is upset that Loretta felt that she needed to take control of the household, to grow up before she should have to. As she hands Loretta a handful of candy, she makes it clear that Loretta should relinquish that kind of responsibility to Mags.

In the next episode, the two share a similar, though more emotionally loaded, moment. She pours Loretta a glass of apple cider, explaining that she is a few years away from being able to have Mags’ apple pie. In part this reads as a warning; Loretta might one day need killing. But mostly, this sentiment is Mags shielding the girl from the poison of her world. As Mags fiddles with Loretta’s jewelry and strokes her hair, she lies to Loretta about her father and confesses her desire to have a daughter instead of being stuck with “just those damn boys.” This scene is replayed later in the season as Mags helps Loretta get dressed up for a picnic, explaining to her that there is nothing wrong in looking pretty and that her [Mags’] time for that is long past. It is in her scenes with Loretta that we most clearly see the regret Mags has for what she has had to become, and what she has had to give up to do so.