|

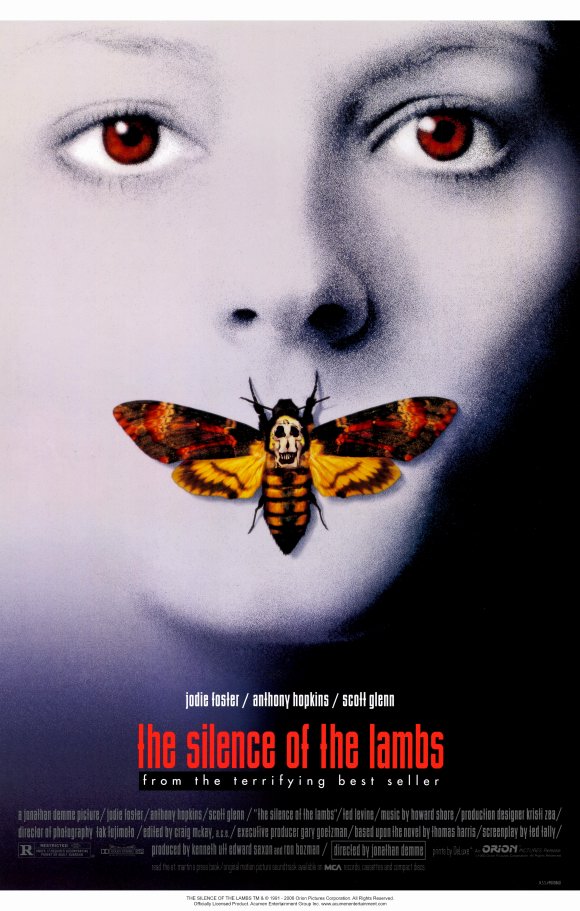

| The Silence of the Lambs (1991) |

This post by Jeff Vorndam is republished with permission.

The horror movie genre has historically exalted the objectification of women. In slasher movies, teen exploitation flicks, and even seemingly innocuous thrillers, women are cast for the purposes of screaming and disrobing. The antithesis within the horror/thriller genre is the 1991 Academy Award winning film The Silence of the Lambs. Although not thought of as a “women’s movie,” a feminist undercurrent is present in the film through its protagonist, a strong female character who contradicts previous genre stereotypes. Her scenes impart an objection to the objectification of women and depict the difficulty of working in a male-dominated institution. Furthermore, her character’s success in the movie is her own doing; there are no male rescuers or helpers.

Jodie Foster plays Special Agent Clarice Starling, the protagonist of The Silence of the Lambs. Starling is an autonomous woman; her mother died at childbirth, and her father was killed in the line of duty when she was ten. She is intelligent (graduated magna cum laude), skilled at her work, and intrepid. Significantly, the film opens with a shot of Starling running alone in the woods, completing an obstacle course in the type of dark sodden forest where one might expect to find a naked dead body. The viewer’s attention is immediately drawn to Starling, and we already sense that she will be in danger. It is the movie’s triumph that it sets our expectation to see her as a doomed victim, and then subverts it by establishing her as a multi-dimensional person in the following scenes.

Roger Ebert wrote about The Silence of the Lambs, “Never before in a movie have I been made more aware of the subtle sexual pressures placed upon women by men.” Ebert refers to the numerous scenes which, taken collectively, give viewers the uncomfortable knowledge that Starling is constantly subjected to stares, condescension, and harassment. By depicting Starling as an object rather than a person in certain scenes, the audience is transposed with her, and feels her apprehension. The first such scene occurs after she is pulled off the obstacle course to meet her superior. There is no dialogue, just a simple shot of Starling, standing 5 feet 2 inches tall in a blue jogging suit, dwarfed and surrounded in an elevator full of burly men over a foot taller than her. Starling stands out even further as an object because her blue sweat suit contrasts with the loud red outfits that each of the men are wearing. It is a situation that any of us would be nervous in, but Starling shows little trepidation. She copes well with the uneasy feeling of the men looming over her. The movie’s self-conscious attempt to display Starling as an object works, though. As an audience, we do feel trepidation.

The same concept applies to a scene in which Starling is holding a punching bag and must withstand the blows of her larger co-workers. The camera’s vantage point is that of the large man delivering the blows. The angle is shot downward so that Starling appears smaller and more vulnerable. Quickly, the viewer sees her as an object–as her male co-workers do as well. It is uncomfortable to watch Starling get hit, and we realize she is objectified this way all the time.

Starling must unfortunately endure many such difficulties because she works in the male-dominated institution of the FBI. As an attractive woman, Starling receives lascivious looks from nearly every male in the movie. When she and her roommate go jogging in one scene, a group of men jogging the other way turn around to ogle the women’s behinds. Earlier, when Starling is looking for Agent Crawford’s (her boss) office, the men gaze at her as if she were an exotic delicacy. Hannibal Lecter’s psychiatrist Dr. Chilton tries to pick her up initially, “Are you familiar with the Baltimore area? I could show you around.” When she explains she has a job to do, Chilton becomes angry, “Crawford sent you here for your looks–as bait.” Lecter surmises that Crawford fantasizes about Starling and that is why she was selected for the assignment. Even the bespectacled etymologist asks her out. In fact, it is only Lecter who is more interested in getting in her head than her pants.

Starling does not simply accept the oppression of her job. Upon arriving at a small town where one of the murder victims has washed up, Starling and Crawford are waiting in a room full of local deputies to see the dead body. The deputies are all staring at Starling, wondering why a woman is with the FBI. Crawford announces it’s time to inspect the body, but adds that Starling may want to stay outside because it’s something that a lady shouldn’t see. Afterwards, in the car on the ride home, Crawford says he didn’t want to offend the local authorities. Starling excoriates him for not setting a better example. By reprimanding her superior officer (while still only a trainee), Starling exhibits her strong personality and stands up for herself. Not only does she rebuff her sexist colleagues though, she is victorious over them.

In most thriller or horror movies (Terminator 2, for example), even if the hero of the story is female, she frequently still requires assistance from males to succeed. In The Silence of the Lambs, Starling succeeds on her own, despite various male interlopers. She cracks the vital points of the case, locates and defeats the killer–with no help save from Lecter. It is arguable what type of “help” Lecter gives her. In exchange for clues to the murderer’s identity, Starling provides Lecter with personal information. Lecter only cooperates with Starling because she is the only person who has treated him with any respect. In fact, as Lecter learns more about Starling’s tragic personal history, he becomes even more impressed with her. In their first meeting he calls her a “rube–one generation up from white trash.” Starling admits that he is perceptive and responds, “…but can you turn that high-powered perception of yours inward on yourself, Dr. Lecter?” At this point, Lecter realizes that he is not dealing with just another suit who’s out to use him–Starling is trying to communicate with him on a personal level. Lecter now sees Starling as a person, and is ironically the only male who does. This is emphasized overtly when Starling finishes talking to Lecter. As she exits the prison, an inmate named Miggs two cells down from Lecter throws his semen at her. Earlier, as Starling makes her way to Lecter’s cell, Miggs screams, “I can smell your cunt!” By framing Starling’s first visit to Lecter with two grotesque symbols of male objectification of women, Lecter stands out further as an asexual mentor.

Critics still point out, however, that without Lecter’s cryptic clues Starling could not have solved the case. Moreover, Lecter uses Starling’s investigation to get himself out of jail. Most damning to the notion that Starling is wholly responsible for her success is the charge that Lecter was sexually attracted to her, and aided her out of lust. These claims are spurious. Recall that Lecter appears to be asexual, especially in comparison with Miggs and Dr. Chilton. Symbolically, Lecter is neither male nor female. He is death incarnate. Director Jonathan Demme always photographs Lecter with a harsh white light on his forehead, the rest of his body ensconsed in shadows. The effect is to give Lecter the appearance of a ghoul. In the only camera shot in which Starling and Lecter are shown together, Lecter’s wraithlike apparition grins like a skeleton next to Starling’s determined composure. When their fingers touch seductively at their last meeting, it is not a sexual advance on Lecter’s part, but the film’s chilling reminder that death’s icy grip is stalking Starling. The movie would not be as frightening without Lector’s embodiment of death.

The victim is the daughter of a female Senator, and, because she fights back against the killer, she is portrayed as strong and independent. In an earlier scene, the victim’s mother makes an announcement on television in which she keeps repeating her daughter’s name–Catherine. After watching the plea, Starling comments that it is good that the Senator kept repeating her daughter’s name, “If he sees her as a person and not an object, it will be harder to tear her up.” Unfortunately, as we see in the next scene, Buffalo Bill refers to Catherine as “it” at all times, even when talking to her: “It places the lotion on its skin.” His goal is to make a woman-suit out of women–the ultimate in objectification.

In the end, Starling purges herself of her inner demons and is victorious. The story vindicates Starling and punishes those who have wronged her. Shortly after Starling’s first visit with Lecter, Miggs chokes on his own tongue and dies. Starling shoots and kills Buffalo Bill. At the end of the film, after Lecter has escaped, he calls Starling to congratulate her. He implies that he is going to eat the sexist Dr. Chilton, “I’m having an old friend for dinner.” Because the “bad sexist” people meet grisly deaths, and Starling is rewarded, The Silence of the Lambs takes a clear stand on the evils of sexism in its denouement.

Jeff Vorndam is a film buff living in the Bay Area. In the past he has reviewed movies for AboutFilm and Cinemarati, but he just watches for fun now. His favorite horror movies include Rosemary’s Baby, Kwaidan, and Martin.