|

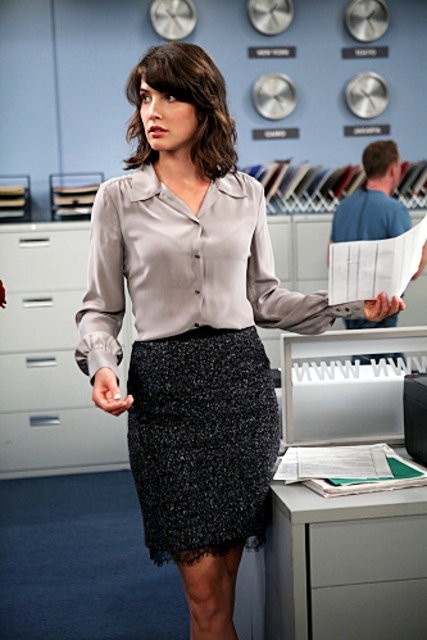

| Alyson Hannigan as Lily Aldrin in “How I Met Your Mother” |

Pregnancy brain. Momnesia. Preggo ladies be cray-cray. Call it what you want, but the idea that pregnant women lose their minds while their hormones go whack is a popular stereotype based on questionable evidence. Some mothers recall feeling forgetful during their pregnancy, while others don’t. (Wow, you’d think different women have different experiences with pregnancy, or something.)

Regardless of how true pregnancy brain is or isn’t, or how different women react to the changes in their bodies, sitcom writers have taken this idea and run with it. Last year, Lily Aldrin experienced an episode’s worth of pregnancy brain on How I Met Your Mother, and this year, Gloria Delgado-Pritchett struggled with her own pregnancy brain problems on Modern Family. The setups were similar: the women had short-term memory problems as a result of their pregnancy hormones. The results, however, were a little different.

On How I Met Your Mother, the characters first notice something different about Lily when she agreed to move to the suburbs, after years of insisting that she would never move to the suburbs and wanted to stay in New York. Marshall, suburban-born and raised, is thrilled that Lily has changed her mind, but Robin warns him that Lily only wants to move because of pregnancy brain. Marshall doubts that pregnancy brain is even a “thing,” and Robin insists that it is: “Her brain is marinating in a cocktail of hormones, mood swings, and jacked-up nesting instincts.” Then Marshall and Robin recall a few incidents of Lily acting strangely: putting her keys and wallet in the freezer and ice cubes in her purse, texting Robin to ask for directions back from the bathroom, and saying “fungus” instead of “fetus” and “metal factory” instead of “mental faculty.” Robin cautions Marshall against letting Lily make any major life choices while pregnant.

This is all just in the first five minutes of the episode, by the way. The point is clear: Lily, while pregnant, is completely incapable of making any decisions for herself and has a more impaired short-term memory than Dory from Finding Nemo. Robin doesn’t think “that moron” can do anything. (Sidebar: why is Robin “I never want kids and have no interest in ever being pregnant” Scherbatsky suddenly an expert in pregnancy brain, anyway?)

|

| Fortunately, Lily has a man by her side! (Hannigan and Jason Segel) |

A year later on Modern Family, Gloria experiences similar symptoms of pregnesia, at a much later stage at her pregnancy than Lily’s. She puts soap in the fridge and butter in the shower. Jay calls his daughter Claire to “babysit the stupid pregnant lady” (Gloria’s words), but he claims that Gloria called Claire and forgot, and she initially believes him. She drives with Claire to Costco and laments over her pregnesia: “I have two brains in my body and I’ve never been so dumb.” Claire tells her not to be too hard on herself: “You have another human being growing inside of you competing for resources.” Claire herself struggled with forgetfulness when pregnant with her daughter Alex (but not so much with her daughter Haley or son Luke). The women exchange a nice moment until Gloria tries to get out of a moving car.

The setup here is slightly different: Gloria is forgetful and scattered, but self-aware enough to know when people are pandering to her. Still, she’s not at her best.

Back on How I Met Your Mother, the plot continues with Lily acting even more ridiculous. She tries to make waffles using a laptop, and Marshall takes advantage of her lapse in judgment by convincing her to buy things for the apartment that she doesn’t really want. Soon, though, she turns the tables on him. She tricks him into thinking that she called a broker to sell her grandparents’ house in the suburbs. Instead, she’s led him to the suburbs on Halloween so they can hand out candy to trick-or-treaters. She’s trying to manipulate him with cute children to convince him to move to the suburbs. It looks like the silly pregnant lady has more “metal factories” than meets the eye.

Meanwhile, on Modern Family, Claire and Gloria go shopping at Costco. Claire has to run to a different part of the store to find a sweater to wear, because Gloria’s been standing in the frozen food aisle for half an hour and can’t remember what she wanted to buy. When the two women finally go to the parking lot after their shop, Gloria accidentally almost closes the door of the minivan on Claire’s head – after all that time, she forgot the eggs. Claire lectures Gloria: “You are purposely turning your brain off!” Then Claire is interrupted by a store’s security guard: she forgot to return the sweater she wore while Gloria stood in the frozen food aisle, and accidentally stole the sweater. Claire tries to plead her case, but the security guard takes her back inside the building.

|

| Sofia Vergara as Gloria Delgado-Pritchett on “Modern Family” |

In the third act of the Marshall/Lily plot on HIMYM, Lily has convinced Marshall to move to the suburbs. Then a few trick-or-treaters come to her door, and she hands them a stapler, scissors, and a bottle of pinot noir. She doesn’t realize what she’s done until Marshall points it out to her, and then she cries because she’s going to miss the stapler. Lily admits that she can’t make any big decisions right now, at least not until she’s done being affected by hormones.

On Modern Family, Claire argues with an overly vigilant store detective. Gloria stands, panicked, and announces that her water broke. Claire and the store detective rush her to the car. As Claire drives, Gloria reveals that she dumped a water bottle on the floor and pretended to go into labor in order to help Claire: “I couldn’t sit there and watch you suffer just because you turned your brain off.” Claire apologizes for pandering to Gloria and doubting her abilities.

Two sitcom episodes, less than a year apart from each other, both dealing with forgetful pregnant women who don’t know how to manage their lives without help, but the message of each episode is very different. The How I Met Your Mother episode is sexist and cliched, while the Modern Family episode attempts to treat the pregnant character with humanity, and mostly succeeds.

Look at the way the other characters talk about Lily and Gloria. Lily is “marinating in a cocktail of hormones,” a “moron,” and acting like the “drunk girl at the bar” – descriptors that would be perfect for a pregnant character on a darker or more satirical comedy, but seem out of place and mean-spirited on a feel-good show like How I Met Your Mother. Claire, on the other hand, initially sympathizes with Gloria, pointing out that pregnancy is draining and of course her memory would be on the fritz.

Lily is also treated like an infant during this pregnancy. She’s not just forgetful – she can’t make any major decisions while these hormones are affecting her brain. SHE IS NOT TO BE TRUSTED. Gloria, meanwhile, is forgetful and scattered, but she hasn’t completely lost her mind, and cleverly saves Claire from the repercussions of her own brain fart.

|

| More similar than you might think (Vergara and Julie Bowen) |

But I think the biggest reason that the Modern Family storyline mostly succeeds and the How I Met Your Mother episode doesn’t is because the first show remembers to show the female perspective on a woman’s issue (imagine that). The episode of How I Met Your Mother isn’t about how Lily deals with pregnancy brain; it’s about how Marshall deals with Lily’s pregnancy brain. Let’s empathize with the poor, long-suffering husband while he deals with the changes in his wife’s body (yawn). Modern Family at least shows us pregnancy-related forgetfulness from the perspective of the female characters. I liked seeing two women bond over their different pregnancies, and I especially liked that Claire didn’t have the exact same experience with every pregnancy.

I don’t know if pregnancy brain is a real thing or not. I’m skeptical, but I’ve had at least two currently pregnant or formerly pregnant friends tell me that they were constantly forgetful during their pregnancies. My impression is that it’s true for some women and not true for others. Both shows exaggerate the concept for for comic effect, but How I Met Your Mother reduces the pregnant woman to an infant and Modern Family remembers that Gloria is still an adult. I know which episode I prefer.

Final thought: if walking into a room with a specific purpose, and then immediately forgetting said purpose for being in that room, is a sign of pregnancy brain, I have been pregnant for the last twenty-eight years. I do this at least twice a day. Maybe pregnant women and scatterbrained artist-writer types are cut from the same cloth.

Lady T is an aspiring writer and comedian with two novels, a play, and a collection of comedy sketches in progress. She hopes to one day be published and finish one of her projects (not in that order). You can find more of her writing at The Funny Feminist, where she picks apart entertainment and reviews movies she hasn’t seen.