Written by Colleen Clemens as part of our theme week on Women Directors.

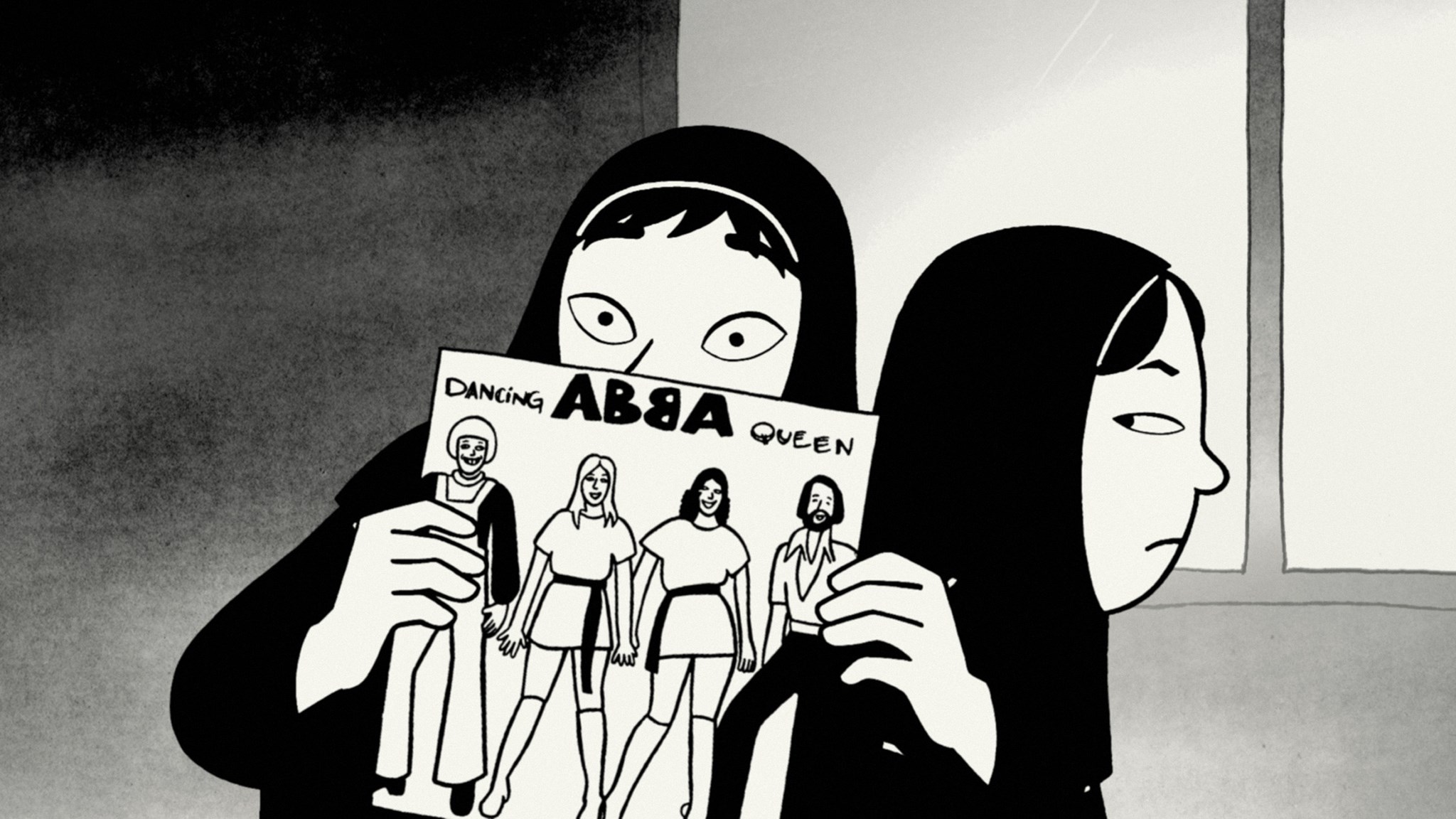

I have been teaching Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novel and film Persepolis for years. I love introducing the young Marji to my students and giving them the opportunity to think about how growing up in Iran may actually share many elements of growing up in the U.S.: jeans, boy troubles, music your parents cannot stand, coming to terms with one’s body.

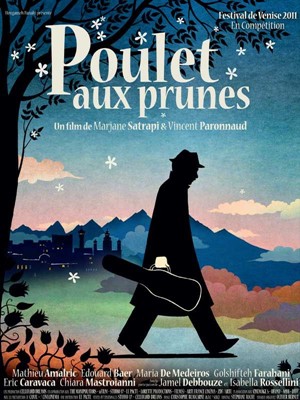

I was eager to see Satrapi’s second film (co-directed with Vincent Paronnaud): a non-animated work, Chicken with Plums, also based on a graphic novel. In the film, the main character, Nasser Ali, is dying. The film counts down the last days of his life and relies on flashbacks to help the viewer understand why Ali is choosing to starve himself to death.

I sat in the dark theater on the last night of the week’s run at the local art house cinema and took notes. But I didn’t leave feeling like I had connected with the film; I didn’t feel like the film offered as much to think about as I had first thought.

And then I realized why I had felt funny about the second film: that in it, he is becoming something — an artist — while the first film deals only with becoming a woman.

There are several reasons why I think it is fair to compare the films even though they look so different. Satrapi wrote both screenplays both based on her graphic novels. Both films deal with a protagonist who is fighting for survival — in the case of Persepolis, how to survive as a woman in an autocratic theocracy and coming of age in a country not of one’s origin and away from one’s family — and the story of Nasser Ali who is spending the entire film dying because he has lost his art because his jealous wife destroyed his violin, the one given to him by his master, whom we will meet later.

In an interview with Mother Jones, Satrapi was asked how she relates to this male protagonist. She replied:

“As soon as I draw a female, I know everybody is going to relate it to me. So even unconsciously there are things that I won’t say. When I create a male character, they wouldn’t know it’s me, so I could just say much more.”

I am interested in the fact that Satrapi finds the freedom to use a male character to investigate becoming something, in this case an artist, a freedom she does not feel when writing a female character that will be conflated with her own self. To summarize this ease, Satrapi told French Culture:

“I said that his hurt musician was the character who was closest to me; because, as he’s a man, I can hide behind me much more easily.”

In an effort to investigate these two main characters, both of which Satrapi admits are autobiographical, we can look more closely at the scenes that deal directly with the main characters coming of age with the guidance of a mentor, in the case of Marji her grandmother, and Nasser Ali, his mentor Agha Mozaffar.

Marji has a close bond with her grandmother, a woman whom has seen her share of revolutions and pain, as members of her family were jailed and killed. She is a tough character who laughs when Marji announces later in the film that she will be getting a divorce and who scolds Marji for using her gender as protection and selling out an innocent man. The two key scenes with the grandmother come at moments where Marji is on the cusp of change. The first is the night Marji is about to leave. A young girl about to go through puberty, Marji is sent to Europe by her parents out of fear for their bright and resistant daughter. In this scene, Marji is spending her last night in Iran with her grandmother.

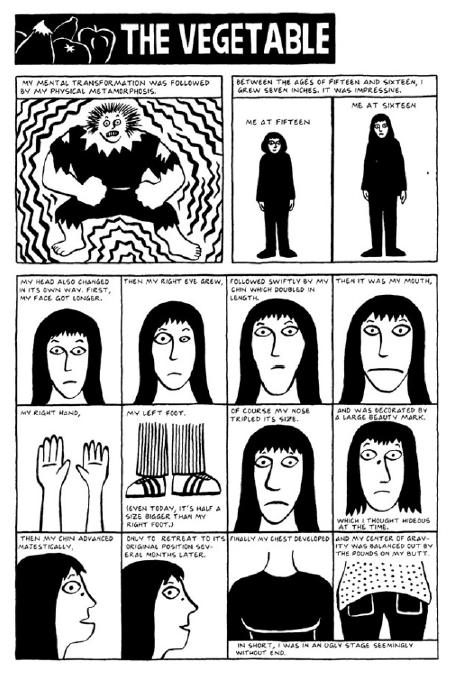

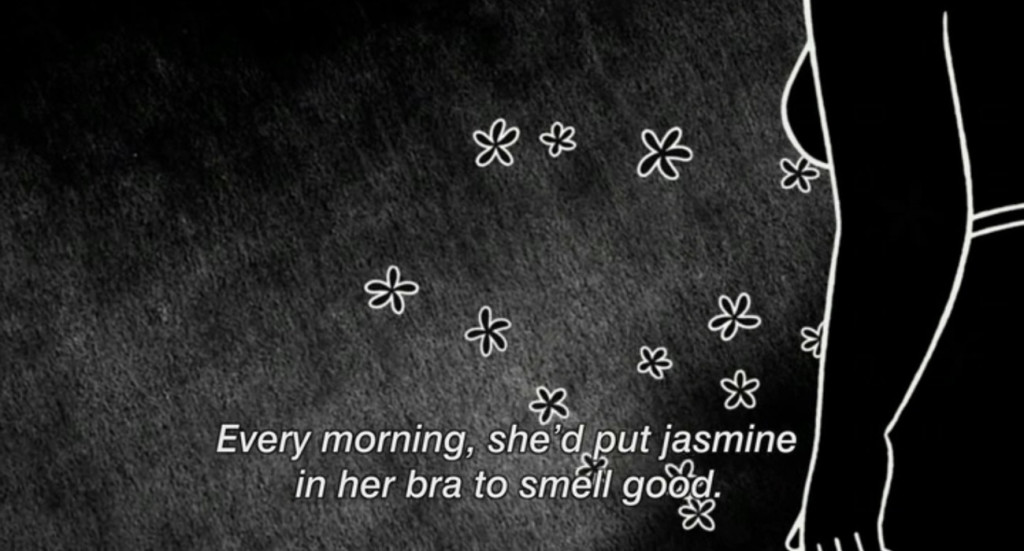

She has to leave Iran to learn what she is to learn in the film: how to become a woman. Marji’s lesson is focused on maintaining her breasts, a signifier of her femininity. Most of what Marji is to learn in this film deals with her gender and her body’s relation to her gender.

The second scene is when the film is ending. Marji has left Iran for good. She is never to return upon her mother’s orders. The last scene hearkens back to the first scene I showed in which Marji learns about her grandmother’s trick to preserve her breasts. We know that the grandmother has died, that she will no longer be there to teach Marji more lessons about being a woman. The film ends with the same flowers drifting imagery, closing the film with a reminder of the grandmother’s femininity.

The grandmother character is used to usher Marji into womanhood. There is no mention of what Marji will do when she is older, just that she will be a woman. Here are several lessons that Marji learns about being a woman: through the story of Nilofaur, Marji learns about sexual violence; through two boyfriends, she learns about sexuality; and through her mother, Marji learns that in order to find freedom as a woman, she cannot stay in Iran. The film spends a great deal of its energy showing how challenging it is for Marji to become a woman, be that an independent woman, but still we don’t see Marji creating anything or doing anything in this bildungsroman.

In contrast we have Nasser Ali, whose gender is also an impediment, but only in that women try to get in the way of him being what he is meant to be: an artist. His mother wants him to settle down and his wife destroys his violin. This film also features a mentorship relationship: that of Nasser with Agha.

In a similar way to Marji, Nasser must be sent far away to have his journey of becoming. There is something in him — talent — that requires he must go beyond his home. But whereas in Marji’s case she must go away to protect herself, Nasser must go away so he can grow, get bigger and fuller and richer.

In the first scene, Nasser meets withs Agha Mozaffa in the faraway place that one must have to work to get to. Even the depiction of this place is mystical, magical, not for everyone. As a young man — and one who’s becoming a man is not a focus of the film — he goes to come of age by learning about love and art.

In the final scene, Nasser comes of age as an artist because he had learned about losing love. In this scene, he will get the tool that he will use to be an artist, just as Marji was given the flower trick by her grandmother, the image that ends the film. Again, the mentor is no longer of use to the student: the lesson is complete and now the character can go out into the world.

But there’s a difference between the world Marji enters and the world Nasser enters: the latter is off to jetset as an acclaimed artist. Marji is in the confines of a cab in the place she doesn’t want to be. She does claim to be from Iran at the end, which in a film about conflicts about identity matters greatly, but she is Iranian and a woman. She is not an artist (though we know that she does become a great one).

I love both of these films for different reasons, but I am concerned that in looking at them as major elements of Satrapi’s body of film work that they mirror the idea Kingsley Browne on The Daily Show stated: “Girls become women by getting older, boys become men by accomplishing something.” Watching Nasser become an artist is satisfying in a way that I don’t necessarily feel when watching Persepolis, even if I do love the work that film does to show the difficulty of forming one’s gender and national identity.

Colleen Clemens is a Bitch Flicks staff writer and assistant professor of non-Western literatures at Kutztown University. She blogs about gender issues and postcolonial theory and literature at http://kupoco.wordpress.com/. When she isn’t reading, writing, or grading, she is wrangling her two-year old daughter, two dogs, and on occasion her partner.