Tag: Documentary

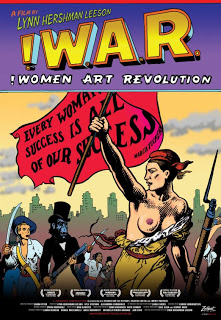

Documentary Review: !Women Art Revolution

So why don’t we know more women in art? It’s a case of omission, of erasing women and their contributions out of history. A stunning film 40 years in the making, “!Women Art Revolution” seeks to fill that gap by combining “intimate” interviews along with visceral visual images of paintings, performance art, installation art, murals and photography.

!Women Art Revolution showcases the controversy swirling around The Dinner Party, Judy Chicago’s infamous exhibit. A powerful feminist installation piece, it consists of a massive triangular-shaped banquet table with 39 place settings. Each plate, utensils, chalice and placemat decorated with colors and iconography unique for the intended guests: various famous women throughout history and myth. Chicago created a groundbreaking piece that puts women front and center, something often lacking in the media. Apparently, The Dinner Party caused the government unease and even outrage. Accused of being pornographic due to the butterfly and floral plates symbolizing the vulva, the U.S.House debated on whether or not it should be displayed. Yes, because vaginas are soooo scary. Some Representatives, all male, said it wasn’t art. Um, who are they to determine that?! One Congressman, a former Black Panther, defended the piece saying it was art and protected as free speech. Sadly, the House passed a bill banning it from being exhibited (Oh that’s right, because Congress has nothing better to do! Sigh). Luckily, when it went to the Senate, a small group of wealthy and influential women urged their Senators to drop the legislation, causing it to be dismissed.

The film covers and interviews the Guerilla Girls, an anonymous watchdog group of gorilla mask-wearing feminist activists combating sexism in the international art world. Formed in 1985, an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art that showcased an international collection of recent artists in painting and sculpture spurred their creation. The exhibit featured 169 artists, only 3 of whom were women. They also looked at the collections in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1989 and found that only 3% of the artists in the modern wing were women and 83% of nude subjects were women. This prompted their famous poster tagline, “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?” The Guerilla Girls protest and continue to speak out, publishing report cards on gender and racial gaps in other museums, galleries and exhibits. They force the art world to face the reality of its own discrimination.

!Women Art Revolution easily could have become dull with dry facts or depressing due to the obstacles the female artists struggled against. Yet it pulses and throbs with fervent energy. Like a little feminist sponge, I soaked up all of the passion, activism and information. With images of women, hearing women’s voices and a score composed by Carrie Brownstein, Sleater-Kinney guitarist and Portlandia actor, the film feels like a safe haven for feminists. In our male-dominated media, it was inspiring to see a riveting documentary created by women and featuring women. My only complaint of the film is that it doesn’t really follow a chronological or thematic order, making it feel a bit chaotic. Yet it also makes it feel raw and personal. Interestingly, Hershman Leeson, almost prophetically anticipating this, admits as much in her own chronology, comprised of various pieces knitted together “like a patchwork quilt.” I found it refreshing that Hershman Leeson’s introspection as a documentary filmmaker leads her to question whether or not she should feature her own art in the film. She comes to the rightful conclusion that she should as women have been omitted from art history for too long.

“Of course I think it has positive connotations for intelligent women and men. But there is still an existing fear of the word itself, as well as miscommunicated baggage of what it represents. This needs revision. Feminism is about cultural values and equality. The young women I am in contact with are grateful to learn about this history. They devour the information. It is, after all, their legacy.”

It is this legacy to future generations that means so much to Hershman Leeson. Arising from the documentary, she started the RAW/WAR project, a virtual community allowing people to submit images of drawings, paintings, performances, dance and music, opening up the dialogue of art and gender to a global community. Also, all of the interview transcripts and many of the videos are available online. As to the message of the film, Hershman Leeson declares:

“As Marcia Tucker reminds us, “humor is the single most important weapon we have!” I think audiences will be inspired by the courage, sense of humor and tenaciousness of the artists who courageously and constantly reinvented themselves and in doing so dynamically revised existing exclusionary policies of their culture.”

Art questions, challenges and inspires. While it can be beautiful and serene, it can also be disturbing and uncomfortable, unnerving the viewer, forcing the audience to look at the world around them. The art in this documentary reveals the media’s incessant agenda of writing women out of history. Society views women’s art, their experiences and stories, as lesser than men’s: less important, less noble, less substantial. When I took Art History in college, I remember we only studied a handful of female artists. The Feminist Art Movement is a chapter ripped out of history, a period most people just don’t know. Whether you’re an art aficionado or not, you simply must see and experience this revolutionary and visionary film for yourself. !Women Art Revolution reclaims women’s narratives and manifests a vocal group of dissenters rattling the cages of constriction and conformity, refusing to be silenced.

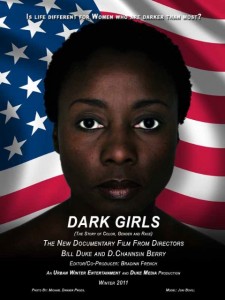

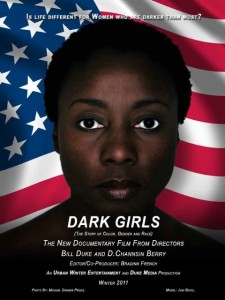

Documentary Preview: Dark Girls

|

| Dark Girls (2012) |

Writing for Clutch, Jamilah Lemieux says:

While many people would love to believe that color is no longer an issue, and that we are post-racial, post-color struck–post-anything that forces them to admit that all things are not even in this world, and that we have much work to do–the many subjects interviewed for the film sing a very different tune.

[…]

Though we know that not all darker sisters suffer great indignities or issues with self image, nor is life a crystal stair for those of us who are lighter, this film continues a long conversation that is still very important. So long as we have people amongst us who gladly uphold the damning “White is right” standard–assigning favor to people based upon their proximity to it, we can’t let this one go. This is something we can get past, this does not have to continue.

Watch the trailer and share your own experiences on the official film website:

Preview: !Women Art Revolution

|

| !Women Art Revolution |

From the official movie website:

!Women Art Revolution elaborates the relationship of the Feminist Art Movement to the 1960s anti-war and civil rights movements and explains how historical events, such as the all-male protest exhibition against the invasion of Cambodia, sparked the first of many feminist actions against major cultural institutions. The film details major developments in women’s art of the 1970s, including the first feminist art education programs, political organizations and protests, alternative art spaces such as the A.I.R. Gallery and Franklin Furnace in New York and the Los Angeles Women’s Building, publications such as Chrysalis and Heresies, and landmark exhibitions, performances, and installations of public art that changed the entire direction of art.

Watch the trailer:

Just for fun, here’s the other poster:

Let us know if you have seen or plan to see this film!

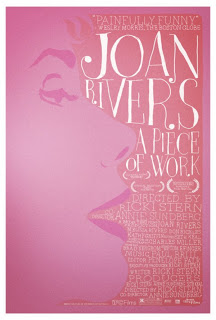

Documentary Review: Joan Rivers: A Piece of Work

|

| Joan Rivers: A Piece of Work |

Watching the film, however, gave me a new appreciation for Rivers–even while not sharing a number of her perspectives. A Piece of Work documents a year in Rivers’ life: she turns 75, faces down a heckler at a stand-up show in Wisconsin, honors George Carlin in a tribute, gets roasted by Comedy Central, and injects new life into her career by winning Celebrity Apprentice. All while still selling that damn jewelry. Her energy level is astounding, and I wonder how she manages to do all she does at the age of 75.

Rivers is an odd character. Being a superstar female comic alone is odd in the U.S.–only a few came before her–but we get a very real look at her life, at the troubles she has faced (her husband’s suicide) and continues to face, and at the loneliness that certainly helps her drive to fill her daily calendar. She is vulnerable and still nervous when going on stage, especially when pursuing what she calls the one sacred part of her life–her acting–in which she hasn’t seen a lot of personal success. I came to find her more compelling and interesting than my initial perception of her, and encourage anyone to see this film and learn more about a woman who refuses to stop.

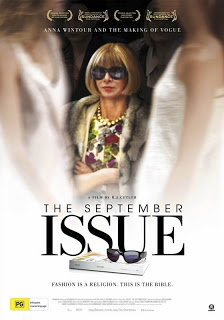

Documentary Review: The September Issue

|

| The September Issue |

I like fashion. It’s an art form, and its creators are capable of beautiful design and cultural statements. It’s also an industry, and like all major industries, has a very ugly side. I liken it to professional sports: I watch from the sidelines, aware of the way I’m being manipulated, but enjoy it nonetheless—all without expressly participating.

Eventually, Coddington gets so palsy-walsy that she puts one of the September Issue cameramen into a last-minute photo shoot as a prop. The resulting pictures are fresh and fun and even manage to make Anna smile, although it’s not clear if she likes the pics or is just enjoying telling a middle-aged cameraman that he’s too fat. When Coddington hears that Wintour wants to Photoshop out his belly, she gets on the phone and threatens the art director and tells him that he has to leave it alone. “Not everything can be perfect in the world,” she rails. It is the climax of the movie, where Coddington eventually triumphs over the tyrant, who has been chipping away at her artistic integrity for the entire 90 minutes.

While Coddington expresses enormous respect for Wintour, she isn’t afraid to speak her mind. Pontificating on the magazine in the back of a car, she mentions how little she likes the rise of celebrity culture and the practice of using actresses as cover models (the fall fashion issue features Sienna Miller on the cover), but concedes that Wintour knew this was the future of fashion mags and put the idea into action first.

Yes, there is drama in the film, and some of it even seems like stereotypical fashion magazine fare, but what remains remarkable is seeing two talented women in their sixties running a fashion empire, working together, clashing over their visions for the issue, all while expressing enormous respect for one another, and doing it all with intelligence and glamour.

Athena Film Festival Mini-Review: Poster Girl

Poster Girl is the story of Robynn Murray, an all-American high school cheerleader turned “poster girl” for women in combat, distinguished by Army Magazine’s cover shot. Now home from Iraq, her tough-as-nails exterior begins to crack, leaving Robynn struggling with the debilitation effects of PTSD and the challenges of rebuilding her life. Directed by Sara Nesson.

Robynn Murray’s trauma was palpable. Her anxiety came through in her near-constant breathlessness, emotional breakdowns, and outbursts of anger. Although she had enrolled in the division of the army sent in after combat missions–to rebuild and ‘win hearts and minds’–she was sent directly into combat. Although women are officially forbidden to participate in combat in the US military, most people will acknowledge that the distinction between combat and non-combat roles is archaic and even non-existent in 21st century war zones. That Murray was assigned a gunner position atop a tank (the most dangerous, exposed position) on the second day of her tour of duty in Iraq shouldn’t surprise the realists among us, but is nevertheless shocking when told from a raw, personal perspective.

Rooting for this film (and, in turn, rooting for its star and director) is enough to make me excited for next weekend’s Oscar ceremony.

Watching Poster Girl was by far the highlight of my experience at the Athena Film Festival. Not only is it a convincing portrayal of the serious effects of post-traumatic stress disorder, but it’s a subtle anti-war film, one that illustrates the often disastrous consequences of repeated exposure to death and violence–and not just for women in combat. Nesson gets moving footage of several former soldiers, including Robynn, who create art from their uniforms, and the soldiers all emphasize the healing power of that process. (I personally loved watching each of them rip their uniforms to shreds.)

Nesson also juxtaposes photos of Robynn prior to her Army experience–where she’s in a cheerleading uniform, smiling and having fun with friends–with the post-Army Robynn, a tattooed, pierced, PTSD victim who stares at the former photos as if they couldn’t possibly be her. And they aren’t anymore. The new Robynn is an activist who speaks out against war and gun violence, even while dealing with debilitating panic attacks.

The film shows just how screwed up our system is for soldiers returning from service: it’s heartbreaking to watch Robynn practically beg for the disability checks the government owes her, as well as witness the lengths she has to go to to “prove” that she’s disabled. But even after all this, Poster Girl somehow ends on a hopeful note, with a smile from Robynn that we hadn’t seen since before she entered the Army.

Watch the preview:

Athena Film Festival Preview

In 2010, for the first time in history, a woman won the Oscar for best director. Directing is the most visible leadership position in film yet, in 82 years, only 4 women have been nominated for best director, and only a single woman has won. In 2009, in the 250 top-grossing domestic films, women made up only 7% of directors, 8% of writers, and 17% of executive producers. 98% of these films had no female cinematographers. And, in front of the camera, as of 2007, women had less than 30% of the speaking roles.

In addition to feature films, documentaries, and short films, there will be events such as “A Hollywood Conversation with actress Greta Gerwig” and a panel on “The Bechdel Test – Where Are the Women Onscreen?” among others.

Here are previews of some of the films we’re planning to see. You can purchase tickets for individual films or a pass for the entire weekend. If you’re in the area, you won’t want to miss this festival!

Chisholm ’72: Unbought & Unbiased

Synopsis from the official site:

Unbought & Unbossed is the first historical documentary on Brooklyn Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm and her campaign to become the Democratic Party’s presidential nominee in 1972. Following Chisholm from the announcement of her candidacy in January to the Democratic National Convention in Miami, Florida in July, the story is like her- fabulous, fierce, and fundamentally “right on.” Chisholm’s fight is for inclusion, as she writes in her book The Good Fight (1973), and encompasses all Americans “who agree that the institutions of this country belong to all of the people who inhabit it.”

The Mighty Macs

Synopsis from the Athena site:

In the early 70s, Cathy Rush becomes the head basketball coach at a tiny, all-girls Catholic college. Though her team has no gym and no uniforms — and the school itself is in danger of being sold — Coach Rush looks to steer her girls to their first national championship.

Miss Representation

Description from the official film website:

Writer/Director Jennifer Siebel Newsom brings together some of America’s most influential women in politics, news, and entertainment to give us an inside look at the media’s message. Miss Representation explores women’s under-representation in positions of power by challenging the limited and often disparaging portrayal of women in the media. As one of the most persuasive and pervasive forces in our culture, media is educating yet another generation that women’s primary value lies in their youth, beauty and sexuality—not in their capacity as leaders. Through the riveting perspectives of youth and the critical analysis of top scholars, Miss Representation will change the way you see media.

There are plenty more films being shown at the festival–be sure to check them out!

The Fat Body (In)Visible

Rabin describes the Fatosphere as follows:

She continues:

Quotes from the documentary: Keena, on Fat Acceptance: Fat acceptance is just accepting your body where it is at. Whether you’re bigger or you’re smaller. Just accepting what it is, your arms, your double chin, your thighs, and just not worrying about how other people may view you.The bloggers’ main contention is that being fat is not a result of moral failure or a character flaw, or of gluttony, sloth or a lack of willpower. Diets often boomerang, they say; indeed, numerous long-term studies have found that even though dieters are often able to lose weight in the short term, they almost always regain the lost pounds over the next few years.

Fat acceptance bloggers contend that the war on obesity has given people an excuse to wage war on fat people and that health concerns—coupled with the belief that fat people have only themselves to blame for being fat—are being used to justify discrimination that would not be tolerated toward just about any other group of people.

Jessica, on Fat Acceptance: Fat acceptance is just the radical idea that every body is a good body and that regardless of your shape or your size that you deserve just as much respect as the next person.

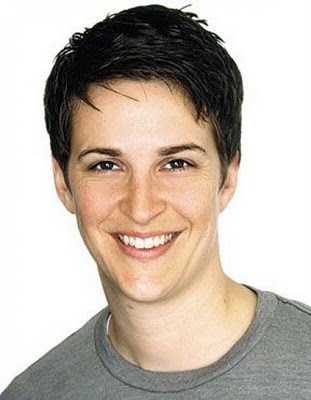

Quote of the Day: Rachel Maddow

Chloe Angyal: Why did you decide to make a documentary about the assassination of Dr. Tiller, and why did you feel so strongly about doing a larger-scale production about the anti-abortion movement?Rachel Maddow: When we covered the Tiller murder when it happened, two things became clear. As soon as you heard last May that a doctor had been killed in Kansas, if you knew anything about the fight over reproductive rights and the radical anti-abortion movement, it was instantly clear that it was George Tiller who was killed, even before you heard the name. I had heard that a doctor was killed in Kansas that Sunday, and knew it was Tiller before I saw in the news that it was Tiller. There are not that many things in America, where you know who’s going to get killed, because there’s a campaign against them that includes people who think that violence up to murder is justified against people with whom they disagree or who they’ve vilified. It’s an unusual thing in America – there aren’t a lot of things like that, so that in itself was shocking enough.

But there was also some smaller scale stuff about our covering it in day-to-day news way. We do daily production, we have to do a show five nights a week, and turn around things in a short time frame, and the Tiller murder and the Roeder conviction were things that we covered intensively, but on this day-to-day production schedule. And one of the things that we didn’t report on, or didn’t really follow up on because it wasn’t appropriate to report on in that day-to-day schedule was the fact that there was a ton of celebration online when Tiller was killed. And you don’t blame people for their blog comments, and you don’t make a news story out of anonymous commenters on the internet machine. If you did, you’d constantly be foretelling the end of the world. It’s not really appropriate to cover that as news, that anecdotal reaction. But reading that reaction online, on Twitter and in blog comments, not just in the dark anti-abortion extremist corners of the internet, but actually in relatively mainstream places, I found very unsettling. It stuck with me and it made me want to do something longer form, more investigative and more in-depth about the murder.

The fight over reproductive rights and the tactics of the radical anti-abortion movement are subjects that are a bummer. It’s something that we think of as almost unendurable, I think, to dwell on, to think about, because it seems like it never gets better, and like the other side never pays a price. And one of the things that I don’t think people have really grasps, which is in this documentary, is the story of George Tiller, who was resolute, cheerful, clever, holistically cognizant of what was going on as he was being attacked in this way.

At Tiller’s funeral, they made giant flower arrangement that said “Trust Women,” because that was his motto. You have to understand the other side, the radicals and their tactics, in order to understand what’s going on in the fight over reproductive rights. But in order to understand the way that people survive this, and the way that people can even hope to win these battles in the long run, understanding the way George Tiller did it is underappreciated. We’ve got these interviews of him that have never before run on television, and you see him, coming back to his clinic the day after he was shot and the day after his clinic was bombed, saying, “What we’re doing is legal. What these people are doing, these terroristic tactics and this anarchy, is illegal,” and putting up the sign outside his clinic: “Women need abortions and I’m going to do them.” And the devotion that his staff had to him, because of that resolution and that resilience that he had, that is a story worth telling about how to live in the face of threat, and how to live in the face of people who are coming at you in ways that are sometimes are very painful to think about. This is a painful story, but this is also an instructive story and a cathartic story for people who support reproductive rights.

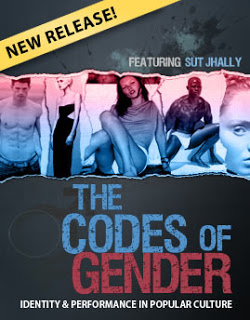

The Codes of Gender: Documentary Preview

From the Media Education Foundation (MEF):

Communication scholar Sut Jhally applies the late sociologist Erving Goffman’s groundbreaking analysis of advertising to the contemporary commercial landscape in this provocative new film about gender as a ritualized cultural performance. Uncovering a remarkable pattern of gender-specific poses, Jhally explores Goffman’s central claim that the way the body is displayed in advertising communicates normative ideas about masculinity and femininity. The film looks beyond advertising as a medium that simply sells products, and beyond analyses of gender that focus on biological difference or issues of surface objectification and beauty, taking us into the two-tiered terrain of identity and power relations. With its sustained focus on the fundamental importance of gender, power, and how our perceptions of what it means to be a man or a woman get reproduced and reinforced on the level of culture in our everyday lives, The Codes of Gender is certain to inspire discussion and debate across a range of disciplines.

I haven’t yet watched The Codes of Gender, but I imagine it might provide some insight for our continued frustration with movie posters.

We previously highlighted Generation M, another documentary by the MEF, which focuses on the misogyny prevalent in contemporary culture.

As the MEF is a foundation focused on education, you can watch a low-resolution preview of any of their films online (for personal viewing only).

If you’ve seen The Codes of Gender, let us know what you think!

Documentary: When Abortion Was Illegal

In this 1992 documentary directed by Dorothy Fadiman, women (and men) tell their stories about illegal abortions, reminding us of the necessity of safe and legal access for women.

The film was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Short in 1993, and is the first in a three-part series about abortion in America.