Here’s the trailer for a fun new movie—coming in January to a theater near you!—from Ron Howard, starring (big voice) Vince Vaughn, Kevin James, and (little voice) Queen Latifah, Jennifer Connelly, and Winona Ryder, about the

conundrum

predicament dilemma (!) in which Vaughn finds himself after discovering that his best friend’s wife is cheating on his best friend.

Even though he calls them, as a couple, his “hero” for their awesome relationship, before uncovering the

quandary

crisis dilemma-producing infidelity, she is only known as his “best friend’s wife,” not, you know, his friend, Geneva. She’s just his best friend’s appendage, not her own autonomous entity with an independent relationship with him, despite the fact they apparently hang out in a big group all the time.

Anyway, the lack of female personhood is probably the least of this movie’s problems, given that the trailer opens with a homophobic joke:

I can’t even imagine what the hilarious reversal is going to be. Is Ryder posing as a beard for James’? Is it an immigration scam? What is the kooky story behind the Very Hot Lady who is cheating on her Stupid Fat Husband?! Boy, I bet it’s a hoot!

With a nod to how awesome our new post-feminist world is, I’d also like to note that Jennifer Connelly has won an Oscar. Winona Ryder has twice been nominated for Oscars. Queen Latifah has been nominated for an Oscar.

Vince Vaughn and Kevin James have both been nominated for Teen Choice Awards.

[Vince Vaughn, wearing a business suit, stands in a corporate conference room, in front of a table of other people wearing business suits, giving a presentation.]

Vaughn: Ladies and gentlemen, electric cars [long pause for comedic effect] are gay. I mean, not homosexual gay, but, you know, my-parents-are-chaperoning-the-dance gay. [His business partner, Kevin James, nods in agreement.] B&B engine design can combine the benefits of electric transportation with the rock-and-rollness of Dodge’s current muscle car models.

James: That we all know and love!

[Queen Latifah, part of the group to whom they’re presenting, nods and smiles appreciatively. Vaughn wow-wows the opening riff of Heart’s “Barracuda” while playing air guitar. Cut to Queen Latifah talking to Vaughn and James in the hall after the meeting.]

QL: I’m inspired by what you’re throwing down, and I got some serious lady-wood here. [She gestures to her crotch.] I want to have sex with your words. [James throws a side-eye at Vaughn.] Gotta go! Mommy and me! I’ll call you! [She waves and runs off.]

Text Onscreen: TWO BEST FRIENDS.

[Cut to Vaughn and James at a smoky bar. Vaughn’s girlfriend is Jennifer Connelly. James’ wife is Winona Ryder.]

Vaughn: Nick, buddy, we got the deal.

James [to Connelly]: I’m not gonna lie—I love your boyfriend. Come in here. [They hug and the girls cheer.] This is great.

Vaughn: Don’t ever let me go.

Text Onscreen: TWO PERFECT COUPLES.

[Cut to a restaurant, where the two couples are sitting around a table. Vaughn and Connelly kiss each other.]

James: I think you can know someone within the first ten seconds of seeing them; I fell in love with Geneva the moment I saw her.

Ryder: Awwww. [She reaches out and strokes James’ cheek.]

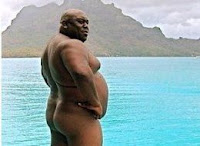

[Cut to James and Ryder on the dance floor; James, because he is fat and intrinsically hilarious, is dancing like a complete arse; Vaughn and Connelly watch from a booth.]

Vaughn: When it comes to couples, they’re my hero.

James: Honey, you hear that? Ronnie told Beth I’m his hero! [Ryder gives an “awwww” look. James turns back to Vaughn.] I’m Mean Joe Green; you’re the little boy with the Coke bottle; come on, I’ll throw ya a jersey! Let’s do it! [More ridiculous dancing.]

Text Onscreen: BUT THIS JANUARY.

[Vaughn, now in some tropical location, sees Ryder with young hot stud, Channing Tatum. He spies on them through the foliage, as “Barracuda” swells.]

Text Onscreen: ONE LITTLE DISCOVERY…

[Vaughn ventures deeper into the foliage for a closer look, ignoring a sign reading: “CAUTION Passiflora incarnata DO NOT ENTER. He sees Ryder and Tatum kissing.]

Text Onscreen: WILL CAUSE A BIG DILEMMA.

[Vaughn trips and falls face-first into a bunch of plants. Cut to Vaughn sitting indoors with two other white dudes, his face all fucked up.]

Vaughn: I just saw my best friend’s wife with another man.

Dude #1 (played by Clint Howard, in his obligatory role in every film of his brother’s): You fell in a whole bed of poisonous passiflora incarnatas!

Dude #2: You can expect diarrhea, fever, dry heaving, painful swelling in your gums, and challenging urination, with a possible bloody discharge. [HA! HIS FRIEND’S WIFE’S CHEATING EVEN RUINED HIS DICK!]

Text Onscreen: From Academy Award winning director Ron Howard.

Vaughn [to some other random white dude in another setting]: Let me ask you a question, and this is completely hypothetical, something way out of left field [continuing as voiceover, over images of Vaughn stalking his best friend’s wife and discovering her with Tatum again]: Let’s say that one friend found out that another friend’s wife was cheating on him…

Dude #3: How good a friend?

[Cut to footage of Vaughn and James at a Blackhawks’ game, doing a choreographed move together.]

Vaughn [back with Dude #3]: Let’s just say his best friend. Very best friend.

Dude #3: I wouldn’t tell him.

[Clips of random people responding to, one assumes, the same question. A black woman says: “It all depends.” A young white dudebro says, “He’s gotta tell him. It’s guy code, man. If you don’t tell your friend, then you’re basically doing her, too.” Cut to Vaughn walking with James at a bar or something.]

Vaughn: Nick, I need to talk to you about something.

James: What’s going on with you?

[Random scenes that make no sense, inserted presumably to show that Things Happen in the movie.]

Text Onscreen: THE DILEMMA.

[Scene of Vaughn peeing and screaming.]

Connelly: Are you all right?

Vaughn: Oh, to be honest with ya, honey, I’m feeling a little challenged. [Hilarious callback to being told he will have challenging urination.]

Text Onscreen: COMING SOON.

She previously contributed a post about the film

She previously contributed a post about the film