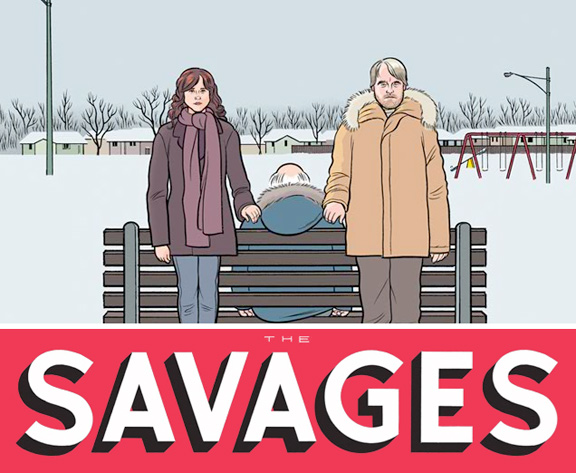

I’ve loved Tamara Jenkins since the first time I saw her film The Slums of Beverly Hills, the 1998 coming-of-age story that put Natasha Lyonne on the map. In addition to being a great movie with top-notch performances by Lyonne, Alan Arkin, and Marisa Tomei, Jenkins shows off her talents as a writer/director willing to show the unsightly, awkward, deeply sad and at once hilarious parts of growing up on the economic margins. The funny moments are made even more so because you don’t seem them coming. As unlikely as you’d be to find a comedic film set in Los Angeles that explores what it means to be a lower-middle-class teenage girl, it would be even more of a rarity to encounter one that delves into what it means to be lower-middle-class adult siblings coping with an estranged parent’s descent into old age and dementia. But that’s just what Jenkins gave us in her 2007 follow-up, The Savages.

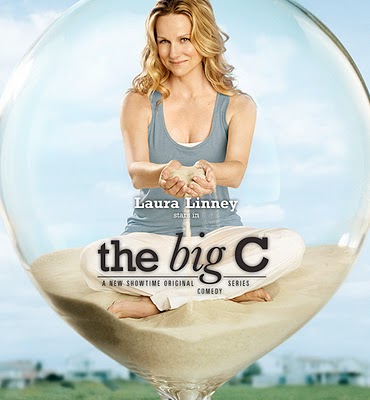

If you’re looking to catch up on any Philip Seymour Hoffman films since we lost him earlier this month then that’s reason enough to watch this film—but only one of many. Here’s another: Hoffman plays opposite Laura Linney, who’s always amazing to watch. The two are Jon and Wendy, brother and sister who must wearily confront the necessity of managing the last days of their father’s life. From the first scene we are faced with the reality of the ugliness that is mental and physical decline: we see their father, Lenny, played by Philip Bosco, being castigated by a home health aide, Eduardo, for not flushing the toilet. We then watch as Lenny walks to the bathroom, and then an uncomfortable amount of time passes until Eduardo goes to check on him, only to find that Lenny’s written the word “Prick” on the wall with his feces. From this point forward it is clear that Jenkins is going to put us front and center with the unrelenting intimacy created when family must deal with each other’s shit.

Shortly after the fecal incident we meet Wendy, a woman in her later 30s sitting in a drab office in Manhattan at what can only be a temp job. Like any aspiring artist stuck at a desk, she is surreptitiously pirating postage, photocopying, and miscellaneous office goodies to service her application process to win grant funding; Wendy’s a playwright shopping around a semi-autobiographical work about her childhood called Wake Me When It’s Over. A combination of her life’s accoutrements tells us she’s not where she wants to be: the temp job, Raisin Bran for dinner, a married man whose dog accompanies him to her apartment when he can steal away for a tryst. We very quickly learn that Wendy is not well-practiced at being honest with herself—or those closest to her. She knows the art of telling people the half-truth if it will earn her some sympathy and/or avoid being scrutinized. Wendy gets a call from Arizona to find that her father, Lenny, is “writing with his shit!” (as she exclaims on the phone to Jon), and her overly righteous response tells us even more about her: she wants to rise to the occasion and save the day by caring for her father who never cared for her.

Jon is far more pragmatic and less willing to give too much compassionate ground to a parent whose absence meant he had to step up and doing a lot of the emotional heavy-lifting for his younger sister. Like Wendy, Jon studies theater, but from an academic side as a professor in Buffalo, New York—a contrast that Jenkins beautifully maps onto their personalities, but with a light touch. Wendy and Jon are far from types, and their sibling dynamic is one marked by distant respect for each other without the pretense of fully understanding the other’s choices. They are not entirely free of judgment and resentment, but they demonstrate ease and kindness toward one another far more often than ire. At the core of their tense moments is the central issue they must reckon with: their father has dementia and they must put him in a nursing home and watch him die.

Wendy has fantasies of setting up Lenny in bucolic quarters in the mountains of Vermont where he can live with independence and comfort. But given the level of Lenny’s dementia and their lack of resources, Wendy has to let go of those dreams and settle for the facility Jon selects, which is far more modest, in Buffalo, with costs covered by Medicare. Another director might have tried to seize the dramatic content of such a conflict, as there’s no downplaying the seriousness of what it means to provide comfort and care to the beloved elderly one’s family. Jenkins, however, brings the funny rather than the dour. When Wendy and Jon take Lenny to a high-end facility for an interview to see if his mental acuity meets their criteria for admission, Wendy attempts to coach her father into giving the correct answers to such questions as “What city are you in right now?” That Lenny doesn’t know is sad, but Wendy’s earnestness to help him cheat is, somehow, delightfully absurd. Jon gets annoyed at his sister, but recognizes the difficulty she’s having with the situation and gently lets her be.

When the inevitable does happen, and Wendy and Jon are free of the obligation that brought them together in a shared purpose, they quietly return to their lives. As is often the case in real life, there is no redemption in their father’s death. Jenkins does give us a kind of postscript wherein Wendy and Jon are still themselves, still trying to do the work that defines them, but they are somehow lighter after having endured Lenny’s illness and death. For one thing, they both make progress moving ahead in ways they were previously stalled (I know that’s vague but I don’t want to spoil too much). Most importantly, though, they have arrived as siblings who want to stay connected even without the anchor of obligation; rather than need each other to fit an idea of family, they just want each other to be happy.