Just kidding! This is another “From the Archive” post…but it’s pretty safe to say that this will be relevant for the summer movie season, as well.

Tag: Amber Leab

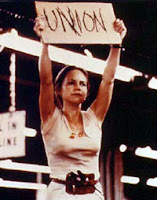

From the Archive: Norma Rae

|

| Norma Rae |

The plot of Norma Rae is inspired by the real life experience of Crystal Lee Jordan, a woman who worked in a North Carolina mill to unionize its employees, spurred on by an out-of-town organizer, until being fired on a bogus charge of “insubordination.” Norma Rae (played by Field, who won the Best Actress Oscar for the role) lives with her parents in the beginning of the movie, and reunites with an old friend who she marries after a brief courtship. As Norma Rae becomes more involved with union activities, the she experiences the usual relationship (romantic, familial, and work) strains, but doesn’t quit until the mill bosses force her out. It’s at this time she makes her famous stand; she refuses to leave, scrawls “UNION” on a piece of cardboard, stands on a table in the middle of a busy factory floor, and stoically remains–in an exhilarating climax to the film–until all her fellow employees shut down their machines and stand with her. She’s arrested and fired in the end, but finishes what she started and believed in.

The plot of Norma Rae is inspired by the real life experience of Crystal Lee Jordan, a woman who worked in a North Carolina mill to unionize its employees, spurred on by an out-of-town organizer, until being fired on a bogus charge of “insubordination.” Norma Rae (played by Field, who won the Best Actress Oscar for the role) lives with her parents in the beginning of the movie, and reunites with an old friend who she marries after a brief courtship. As Norma Rae becomes more involved with union activities, the she experiences the usual relationship (romantic, familial, and work) strains, but doesn’t quit until the mill bosses force her out. It’s at this time she makes her famous stand; she refuses to leave, scrawls “UNION” on a piece of cardboard, stands on a table in the middle of a busy factory floor, and stoically remains–in an exhilarating climax to the film–until all her fellow employees shut down their machines and stand with her. She’s arrested and fired in the end, but finishes what she started and believed in.

Norma Rae isn’t a super mother, nor does she fit the description of a woman we’re typically supposed to look up to. She’s made mistakes in her life and she’ll probably make a few more. She’s not looking to move away from her roots and improve her life based on others’ terms; she doesn’t act out of selfish desire. In other words, she’s a rarity in film: a real woman.

Quote of the Day: Janet McCabe

|

| Feminist Film Studies: Writing the Woman into Cinema |

Leading comedic roles for women in film and television are often relegated to “romantic” comedy and these women still, in 2011, struggle to break into the classification of comedy–without modifiers–and remain relegated to the dreaded “chick flick” (a term that the title of this website plays off of).

From the section “Romantic comedy and gender” in the book Feminist Film Studies: Writing the Woman into Cinema.

Television comedy is another area of recent feminist inquiry, which investigates in particular star performance, joke-making techniques and the television audience. Alexander Doty (1990), investigating the interplay between the star image of Lucille Ball and the character she plays in I Love Lucy (Desilu Productions Inc/CBS, 1951-57) argues that Lucy Ricardo is constructed as the zany, loveable, ditzy and talentless housewife and mother based on the denial, repression and (re)construction of Ball’s star image. Patricia Mellencamp (1997) is another scholar fascinated by Lucille Ball’s slapstick routines. Recuperating Ball’s performance as an act of defiance from the confinement of the domestic space allows her to locate the radical underpinnings of the show for female viewers. Each week Lucy unsuccessfully attempting to escape domesticity and break into show business. They physical comic routines performed by Ball offered a means of challenging patriarchy as she upstages her husband/other men; and this is what audiences tuned in to see. Drawing on Freud’s theory of humorous pleasures (that is, humour used to avoid emotional pain) enables Mellencamp to argue that laughter directed at Lucy’s performance of being talentless – ‘her wretched, off-key singing, her mugging facial exaggerations and out-of-step dancing [is] paradoxically both the source of the audience’s pleasure and the narrative necessity for housewifery’ (1997: 73). She contends that Lucy’s situation made visible the real dilemmas faced by many women: ‘Given the repressive conditions of the 1950s, humour might have been women’s weapon and tactic of survival, ensuring sanity, the triumph of the ego, and pleasures’ (ibid).One of the most sustained discussions on gender, representation and cross-cultural theories is Kathleen Rowe’s study of the unruly woman (1995). Using theoretical models from Mikhail Bakhtin concerned with the grotesque, Rowe identifies the grotesque body as ultimately the female body – often an outrageous, voluptuous, loud, joke-cracking dissenter or ‘woman on top’. The unruly female is not about gender confusion but inverting dominant social, cultural and political conventions; unruliness occurs when those who are socially or politically inferior (normally, women) use humour and excess to undermine patriarchal norms and authority. Focusing on Roseanne Arnold allows her to suggest how Roseanne’s star image and her television situation (Carsey-Werner Company/ABC, 1988-1997) disrupt and expose the gap between feminist liberation (informed by second-wave feminism) and the realities of working-class family life (those of whom feminist liberation left behind), between ideals of true womanhood and unruliness to challenge notions of a patriarchal construction of femininity. Making a spectacle of herself – her overweight body, her physical excesses, her performance as loud and brash – reveals ambivalence as the unruly woman speaks out. Difficulties faced by Roseanne in the press with the vitriol directed at her ‘make known the problems of representing what in our culture still remains largely unrepresentable: a fat woman who is also sexual; a sloppy housewife who’s a good mother; a “loose” woman who is also tidy, who hates matrimony but loves her husband, who hates the ideology of true womanhood, yet considers herself a domestic goddess’ (1995:91).As I hope is clear, feminist critics disclose how television culture is informed by context and given meaning through the ways in which particular programmes are consumed, how narratives are experienced and what they mean to the female viewer – what television series says about women and how media texts function in their daily lives. Through interviews, Deborah Jermyn (2003) analyses how women talk about the series in an effort to understand what Sex and the City (HBO, 1998-2004) means to female fans. Pivotal here is the point at which Jermyn’s own fandom intersects with the experience of those she interviewed – it is a moment that allows her to reveal both the pleasures and difficulties involved in understanding how fan culture operates and how to speak about it.

What leading women of comedy since the 90s reach across gender divides and avoid the ghettoization of the “chick flick?” Who are the new “unruly” women? Does Tyler Perry’s Madea count? (I’m only half joking here.) I’d love to hear readers’ thoughts on these matters.

The Grass is Not Always Greener: On Body Image and Illness

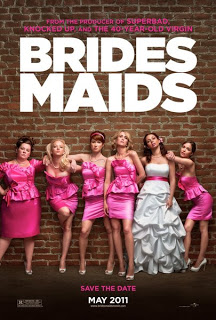

Question of the Day: Are You Going to See Bridesmaids?

Preview: Prom

Director Spotlight: Tanya Hamilton

|

| Filmmaker Tanya Hamilton |

There aren’t a lot of black women making movies, which I find interesting in a way. I’ve blindly not really thought of it. I’m race obsessed, and that has been the lens through which I walk through the world. Making the film has made me think about my gender in a way I had previously not bothered [to]. Film is a very male-dominated world, and those positions are very protected. I think it’s interesting in terms of what gets defined as a woman’s film as opposed to a regular film. I haven’t figured it out yet. I don’t have a theory — at least not a smart one.

One is a thriller/love story set in Jamaica during a violent election. The other is a film about two brothers in fledgling Native American tribe building their first casino and confronting the unforgiving world of D.C. politics to achieve their goal.

|

| Night Catches Us |

In the summer of ’76, as President Jimmy Carter pledges to give government back to the people, tensions run high in a working-class Philadelphia neighborhood where the Black Panthers once flourished. When Marcus returns—having bolted years earlier—his homecoming isn’t exactly met with fanfare. His former movement brothers blame him for an unspeakable betrayal. Only his best friend’s widow, Patricia, appreciates Marcus’s predicament, which both unites and paralyzes them. As Patricia’s daughter compels the two comrades to confront their past, history repeats itself in dangerous ways.

Refusing to romanticize Black Power, Hamilton chooses the riskier path of examining its emotional and political fallout. The bullet holes and bloodstains that Iris uncovers after peeling away a strip of wallpaper at home suggest that her father died not as a martyr for the cause but as yet another senseless casualty in an endless conflict, with police harassment of African-Americans by the nearly all-white Philly force still continuing in ’76. Jimmy’s parroting of black macho, in turn, leads only to more spilled blood.

Hamilton doesn’t rush to supply answers. She lets her mesmerizing movie sneak up on you and seep in until you feel it in your bones. The fact that Hamilton studied painting at Cooper Union helps the images resonate, as does the haunting lighting supplied by cinematographer David Tumblety. Add a terrific score supplied by the Roots and the movie has you in its grip. Mackie and Washington could not be better; they had me at hello. Night Catches Us is essentially a ghost story, with the past persistently intruding on the present. Hamilton manifests her vision of what politics can do to individual thinking with subtlety and sophistication. Remember her name. She’s a genuine find.

Short Film: Tech Support

Tech Support is a short film written and produced by Jenny Hagel. The film has won several awards–including Best Lesbian Short at the Hamburg International Queer Film Festival (Germany), the Audience Award at the Pittsburgh International Lesbian and Gay Film Festival, and Best Short Film at the Fresno Reel Pride LGBT Film Festival–and has been an official selection at 16 film festivals.

Watch Tech Support:

Be sure to also check out Hagel’s very funny Feminist Rapper series: A Lady Made That, Real Ladies Fight Back, and This Is What A Feminist Looks Like.

Preview: !Women Art Revolution

|

| !Women Art Revolution |

From the official movie website:

!Women Art Revolution elaborates the relationship of the Feminist Art Movement to the 1960s anti-war and civil rights movements and explains how historical events, such as the all-male protest exhibition against the invasion of Cambodia, sparked the first of many feminist actions against major cultural institutions. The film details major developments in women’s art of the 1970s, including the first feminist art education programs, political organizations and protests, alternative art spaces such as the A.I.R. Gallery and Franklin Furnace in New York and the Los Angeles Women’s Building, publications such as Chrysalis and Heresies, and landmark exhibitions, performances, and installations of public art that changed the entire direction of art.

Watch the trailer:

Just for fun, here’s the other poster:

Let us know if you have seen or plan to see this film!

Preview: Pariah

|

| Pariah (2011) |

Based on a short film Rees originally premiered at Sundance in 2007, “Pariah” centers on Alike (an excellent Adepero Oduye), a 17-year-old Brooklyn girl who is struggling to find herself as a lesbian and, just as importantly, a young woman. She know’s she’s gay, but is she the more masculine, boyish dyke who hits the underage dance hip-hop dance clubs that her best friend Laura (Pernell Walker) wants her to be? Or, is she the more socially conscious hipster poet her new friend Bina (Aasha Davis) sees in her? These are the rarely depicted voices in America that Rees embraces as common place which is one of the reasons “Pariah” feels so special.

As we delve into Alike’s world, which is meticulously painted by director Dee Rees, from the standout music selections to the infuriating control Audrey insists on lording over her daughter, we discover nuanced performances from each member of the talented cast. Nothing in Alike’s life is black or white and it is those precarious gray areas that Rees navigates so beautifully as we go on this journey. PARIAH is subtle in its effect and draws viewers in to the story rather than telling it to them.

Quote of the Day: Monica Nolan

|

| bitchfest |

In the 1940s and ’50s, when wartime taught women that they could be economically successful on their own, and as divorcees and widows became more common, Hollywood switched gears. Single moms, here transformed into the dreaded “career women,” were now messing up not their kids’ economic chances but their psyches. The most spectacular example was the 1945 classic Mildred Pierce, in which Mildred kicks out her deadbeat husband and builds a successful restaurant chain, only to have one daughter die and the other turn into an amoral murderess.[…]In Baby Boom, Diane Keaton’s J.C. is a high-powered Manhattan exec who suddenly inherits a baby. Initially, this looks like a radical twist on the Three Men and a Baby concept, as the film introduces the idea, in several comic sequences, that motherhood is no more instinctual for women than it is for men. But before the audience can grab another handful of popcorn, she’s quit her job and fled to a farmhouse in Vermont, a move that the plot reassures us is all for the best: J.C. has always dreamed of a house in the country. In this movie, children don’t entail real sacrifices, just changes that turn out to be redemptive. It’s the baby’s job to feminize Mom and, in the process, save her from the rat race.[…]A single mom and her kids are by definition a family without a father, and the female-headed household is destruction of the patriarchy at its most basic level. Needless to say, in Hollywood, showing its unproblematic success is still a huge taboo. Contemporary single-mom films are truly reflective of our culture: A massive amount of energy is expended in a desperate attempt to prove that single parenthood is not good enough, even as an ever-increasing number of women parent on their own. (It’s important to note that this anxiety manifests itself onscreen with an almost exclusive focus on white, middle-class single moms, despite the fact that more than one-third of American single moms are women of color. Though this is part and parcel of the overwhelming whiteness of Hollywood in general, it conveniently allows mainstream films to ignore the factors of class and race that are inextricably intertwined with single parenthood.

Director Spotlight: Jane Campion

|

| Filmmaker Jane Campion |

Jane Campion was born in Wellington, New Zealand, and now lives in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Having graduated with a BA in Anthropology from Victoria University of Wellington in 1975, and a BA, with a painting major, at Sydney College of the Arts in 1979, she began filmmaking in the early 1980s, attending the Australian School of Film and Television. Her first short film, Peel (1982) won the Palme D’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1986.

|

| Sweetie |

Explores sisters, in their twenties, their parents, and family dysfunctions. Kay is gangly and slightly askew, consulting a fortune teller and then falling in love with a man because of a mole on his face and a lock of hair; then, falling out of love when he plants a tree in their yard. Sweetie is plump, imperious, self-centered, and seriously mentally ill. The parents see none of the illness, seeing only their cute child. Kay mainly feels exasperation at her sister’s impositions. Slowly, the film exposes how the roots of Sweetie’s illness have choked Kay’s own development. Can she be released?

The first time I saw it, at the 1989 Cannes Film Festival, I didn’t know what to make of it. I doubted if I “liked” it and yet it was certainly a work of talent. There was something there. I didn’t feel much from it, though; the experience seemed primarily cerebral. Then six months later I saw “Sweetie” a second time, and suddenly there it all was, laid out in blood and passion on the screen, the emotional turmoil of a family’s life.

Watch the trailer:

|

| The Piano |

A mute woman along with her young daughter, and her prized piano, are sent to 1850s New Zealand for an arranged marriage to a wealthy landowner, and she’s soon lusted after by a local worker on the plantation.

Like “Sweetie,” Ms. Campion’s marvelous first feature, “The Piano” is never predictable, though it is seamless. It’s the work of a major writer and director. The film has the enchanted manner of a fairy tale. Even the setting suggests a fairy tale: the New Zealand bush, with its lush and rain-soaked vegetation, is as strange as the forest in which Flora says her mother was struck dumb.

Trips through this primeval forest are full of peril. When Ada goes off to her first assignation with Baines, she appears to be as innocent as Red Riding Hood. Yet this Red Riding Hood falls head over heels in love with the wolf, who turns out to be not a sheep in wolf’s clothing, but a recklessly romantic prince with dirty fingernails.

Watch the trailer:

|

| The Portrait of a Lady |

Isabel Archer, an American heiress and free thinker, travels to Europe to find herself.

Instead of faithfully reiterating James’s novel, Ms. Campion chooses to reimagine it as a Freudian fever dream. Fantasies intrude; prison bars or doorways or mirrors offer tacit commentary; the story’s well-bred heroine abruptly sniffs her boot or tries to hide an undergarment hanging on a door. With startling intuitiveness, Ms. Campion traces the tension between polite, guarded characters and blunt visual symbols of their inner turmoil.

|

| In the Cut |

Following the gruesome murder of a young woman in her neighborhood, a self-determined woman living in New York City–as if to test the limits of her own safety–propels herself into an impossibly risky sexual liaison. Soon she grows increasingly wary about the motives of every man with whom she has contact–and about her own.

Ann Hornaday, writing for The Washington Post, says

These tricky sexual dynamics clearly interest Campion more than the thriller elements of “In the Cut,” in which Frannie has a tendency to walk into dark basements and get into strange men’s cars at a rate clearly disproportionate to her intelligence. The red herrings are trotted out almost by rote, with no finesse or subtlety, as are frequent outbursts of gratuitous gore. By the movie’s ludicrous conclusion, viewers will have abandoned all hope of getting the mature thriller they might have paid to see.

But if “In the Cut” fails as a thriller, it’s not such a write-off as a psychosexual portrait of a certain kind of single Manhattan woman at the turn of the new century. With its restless, jittery camera, the movie captures the jangly paranoia of a city that is often equally tantalizing and threatening; Frannie responds in kind, with her own contradictory sexual persona, which at certain times is defiantly autonomous and at others almost timidly girlish. A “Looking for Mr. Goodbar” for the post-9/11 age (the remnants of that tragedy form one of the movie’s many visual leitmotifs), “In the Cut” focuses on the darker face of the classic New York romance.

|

| Bright Star |

Campion returned to critical acclaim with Bright Star, the story of poet John Keats’ first love and subject of his poem “Bright Star,” Fanny Brawne. The film is based on their 3-year romance.

Dana Stevens, writing for Slate, says of Bright Star

Keats proves as tough to demythologize as Marilyn Monroe: He died so young, his life was so tragic, and the small body of work he left behind is so incomparable, that any depiction of his short life is bound to be tinged with idealization.

That’s why Campion was smart to make her film less about Keats than about Fanny Brawne, the fashionable, flirtatious young woman who captivated him in the spring of 1818 and lived next door to him in Hampstead for the last two years of his life. Fanny, as played by the up-and-coming Australian actress Abbie Cornish, is a curious heroine.

Salon‘s Stephanie Zacharek says

Poetry gets a bad rap almost everywhere: In school, where many of us read it because we have to; in life, where most of us don’t read it at all; and in the movies, where it’s often quoted by the most pompous character or, worse yet, in a self-serious voice-over. Even people who like poetry well enough often fail to revisit poems they once connected with as young students.

If you’re in that last group, Jane Campion’s “Bright Star” just may be the film to reconnect you. And if you’re not, the film works on its own as an unfussy, passionate and gently erotic love story that never tips into sentimentality.

Watch the trailer: