|

| A Royal Affair (2012) |

The radical notion that women like good movies

|

| A Royal Affair (2012) |

At the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, I was a child and only vaguely aware of the crisis as hundreds of people, mostly young gay men at that time, were dying from an unknown virus with no cure in sight. As a teen in the late eighties and early nineties, I do remember seeing the “Silence = Death” posters, t-shirts, and buttons with the iconic pink triangle, but I realize now that I did not know the full scope of what it all meant. So I was intrigued to watch the documentary How to Survive a Plague directed by journalist David France. Nominated this year for an Oscar in the Best Documentary Feature category, How to Survive a Plague chronicles the organization ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) and its offshoot TAG (Treatment Action Group) from 1987 to 1996 and these organizations’ dedicated efforts to pressure the United States government and other authorities to prioritize HIV/AIDS research and treatment and to approach the epidemic as a healthcare emergency and not merely an isolated scourge among homosexual men.

| “Silence = Death” |

Director David France, who was a journalist at the time these events were unfolding, has said that his goal as a journalist and then as a filmmaker was to bear witness. Consequently, the film is a very detailed account of the power of grassroots activism. Not only did these activists–gay and straight, young and old, male and female, healthy and dying–use protest in the streets as a means of garnering attention to what activist and playwright Larry Kramer described as a plague that was killing hundreds of thousands, but they educated themselves and became experts on medical research, experts at navigating the bureaucracy of drug testing and drug approval protocols, experts on creating policies for the treatment of HIV/AIDS patients, experts at wrangling the media, and experts at placing pressure on key decision-makers in the FDA and NIH. The activists also partnered with and prodded drug companies to find and manufacture drugs to treat the disease. In fact, ACT UP and TAG’s open dialogue with scientists at pharmaceutical companies like Merck & Co. ultimately lead to the discovery of the combinations of protease inhibitors which have stopped HIV/AIDS from being a death sentence.

Although the movement was very successful, it was not without its drawbacks. Activists interviewed stated great disappointment when drugs for which they had advocated for and invested much time and resources did not ultimately work on the virus or its symptoms. Many activists did not survive to see the fruits of their labor realized. Indeed, a very poignant part of the film is when activists march to the White House, occupied at that time by President George H. W. Bush, and dump the ashes of their loved-ones on the lawn while yelling “Shame!” The documentary also explores some of the internal politics and strife that occurred within ACT-UP over the years as personalities clashed over the direction and focus of the movement. This strife led to a segment of ACT-UP leadership breaking off and forming TAG. Fortunately, neither organization allowed politics to derail their existence or the ultimate goal.

To his credit, France tempers the emotional frustration and urgency that permeates the film with moments of humor. One of my favorite scenes was footage of TAG activists placing a giant condom over the home of the late Senator Jesse Helms. And as I watched other archival footage of protesters with signs saying “Healthcare is a Right” scrolling across the screen, I was struck by how much the echoes of the past tend to reverberate in the present. The activists featured in this film — through their tireless work, their courage, and their deafening lack of silence — saved millions of lives. (The film states that more than 6 million lives have been saved since 1996 when the three-drug combination of protease inhibitors was identified as a viable treatment). But the fight is not over because there is still no cure for HIV/AIDS, the virus is still spreading worldwide especially among communities of color, and millions of people cannot afford and/or have no access to the life-prolonging drugs that are now available. And so the greatest take-away from How to Survive a Plague is the knowledge that silence is still not an option.

———-

Diana Suber is a movie-loving lawyer who lives in Atlanta. She writes movie reviews and other thoughts on film at her blog http://www.atlflickchick.com/.

|

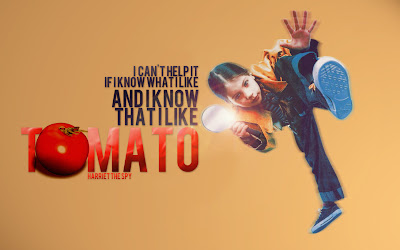

| “I can feel the strongness. I feel like I can move almost anything in the world.” – Matilda |

|

| “You’re an individual, and that makes people nervous. And it’s gonna keep making people nervous for the rest of your life.” – Golly |

|

| “I’m Pippilotta Delicatessa Windowshade Longstocking, daughter of Captain Efraim Longstocking, Pippi for short.” – Pippi |

|

| “My name is Paikea Apirana, and I come from a long line of chiefs…I know that our people will keep going forward, all together, with all of our strength.” – Pai |

|

| “Hello. I am Princess Moanna, and I am not afraid of you.” – Ofelia |

|

| “Kissing requires a total of thirty-four facial muscles.” – Hanna |

|

| “For my will is as strong as yours, and my kingdom is as great. You have no power over me!” – Sarah |

I don’t even want to disgrace the hallowed web pages of Bitch Flicks with an obvious account of the worthless Twilight series that equates female sexuality with death and advocates teen pregnancy over reproductive rights. However, Bella is a prime example of a young woman whose own self-value is dependent on how the male characters view her. She is the apex of a noxious love triangle, and her desirability defines her, creating the entire basis of the poorly acted, poorly produced saga.

|

| “It’s like diamonds…you’re beautiful.” – Bella re: Edward’s sparkly skin. Gag, Puke, Retch |

Ginger Snaps clearly fits the mold of the vilification of budding female sexuality. Ginger gets her period for the first time and is therefore attacked by a werewolf. The attack has rape connotations, implying that Ginger wouldn’t have been as enticing to the wolf if she weren’t yet sexual, especially since her mousy sister Brigitte is spared. Ginger goes through a series of changes, becoming sexually aggressive and promiscuous. When she has unprotected sex with a boy, turning him into a werewolf, this further underscores the connection between Ginger’s monstrous lycanthropy and her unchecked sexuality. There’s also a great deal of sexual tension between Ginger and her sister, Brigitte, suggesting that her sexuality is boundless and therefore frightening.

|

| “I get this ache…and I, I thought it was for sex, but it’s to tear everything to fucking pieces.” – Ginger |

Lastly, we have the pseudo-feminist film Teeth about a young girl who grows teeth on her vagina (vagina dentata style). Our teenage heroine, Dawn, is in one of those Christian abstinence/purity clubs, and everything is fine until she becomes attracted to and makes out with a boy. The film punishes her for her newfound sexuality and mocks her abstinence vow by having the boy rape her. Dawn’s vagina then bites off his penis. Over the course of the movie, Dawn is essentially sexually assaulted four times. Four times. She is degraded from the beginning of the film to the very end. Her supposedly empowerful teeth-laden vagina is a dubious gift, considering she generally must be raped in order to use it. Instead of focusing on the power of her sexuality and the awesome choice she has of whether or not to wield it, the film victimizes her at every corner, undercutting her potential strength and sexual agency.

|

| “The way [the ring] wraps around your finger, that’s to remind you to keep your gift wrapped until the day you trade it in for that other ring. That gold ring.” – Dawn |

Basically, Brave isn’t really that brave of a film. It’s traipsing through a well-established trope that, though positive, is stagnant. Don’t get me wrong; I love all the prepubescent female power fantasy tales I’ve listed, and I’m grateful that they exist and that I could grow up with many of them. However, we can’t pretend that Brave is pushing any boundaries. It sends the message that little girls can be powerful as long as they remain little girls. The dearth of representations of postpubescent heroines who are not objectified, whose sexuality does not rule their interactions, and who are the heroes of their own stories is appalling. There may be exceptions, but my brain has a fairly to moderately comprehensive catalog of films, especially those starring strong female characters. Scanning…scanning…file not found. If I, who actively seek out films that use integrity in their depictions of kickass women, can’t think of many, how is the casual viewer to find them? How is the teenage girl coming into her sexuality while facing negativity and recriminations supposed to see herself portrayed in a light that gives her the opportunity to be nuanced, to be smart and brave, to be independent or to be a leader?

———–

When Tarantino understandably felt uncomfortable with the thought of filming scenes of a slave auction and brutality against slaves, he struggled with not wanting to film those scenes in the American south. He sought advice from Sidney Poitier (the first African American to win a Best Actor Oscar). His response:

“‘Sidney basically told me to man up,’ Tarantino says. ‘He said, ‘Quentin, for whatever reason, you’ve been inspired to make this film. You can’t be afraid of your own movie. You must treat them like actors, not property. If you do that, you’ll be fine.'”

Overall, Tarantino was fine. His Black actors, however, were not recognized for their performances (this was reminiscent of his 1997 film Jackie Brown, which received Golden Globe nods for Samuel L. Jackson and the title character, Pam Grier, but only received an acting Academy Award nomination for white co-star Robert Forster).

In an Oscar year that feature films that deal with race (The New York Times recently published an excellent article examining race and the roles of Black men in this year’s Oscar contenders), the acting awards nominations are startlingly white (Denzel Washington and Quvenzhané Wallis being the exceptions).

[Warning: spoilers ahead!]

|

| Quvenzhane Wallis as Hushpuppy in Beasts of the Southern Wild |

Guest post written by Laura A. Shamas, Ph.D.

Later, the water serves as a source for spiritual cleansing; Hushpuppy embarks on a search for her mother, and finds maternal nurturing from women who work aboard a pleasure ship, the “Elysian Fields Floating Catfish Shack” featuring “Girls Girls Girls.” Wink’s passing, with final ship burial rites that are similar to those of the ancient Vikings, is connected to a spiritual return to the sea.

The theme of “regeneration” is clear in the ending of Beasts of the Southern Wild, and discussed in further detail below. Much more than a mere setting, water is part of every major plot turn, and somehow young Hushpuppy must learn to live with it, on it, and sail through it.

|

| Beasts of the Southern Wild |

Classic tales from traditions worldwide feature flood motifs. The Sumerian Epic of Atrahasis predates Noah’s story; ARAS’ The Book of Symbols says the Atrahasis tale “describes casualties of flood strewn about the river like dragonflies.” [vi]

The familiar story of Noah’s Ark is one of many legends in which the deluge brings a renewal, the start of a new cycle, even a rainbow. In the Gilgamesh Flood Myth (which some scholars trace to The Epic of Atrahasis), Upnatishtim must build a boat to weather a storm so foul its verocity frightens the very gods who created it. Like Noah, Upnatishtim’s boat eventually lands atop a mountain.

In the Irish legend of Fintan mac Bóchra, Fintan escorted one of Noah’s granddaughters to Ireland. As one of three who lived through the deluge, Fintan “the Wise” survived the deluge by shape-shifting into a salmon and two birds; eventually he became a human again and advised the ancient Kings of Ireland. A Kikuyu story (Kenya) tells of spirits drowning a town with beer, as inhabitants find refuge in a tavern.

In China, the tales of “Yu The Great” center on flood fighting, with family sacrifices as part of the battles, and supernatural assistance in the form of a yellow dragon, or in some versions, Yu is the dragon. [vii] An ark features prominently in the Greek myth of Deucalion and Pyrrha, Prometheus’ son and Pandora’s daughter, who survive a flood unleashed by Zeus. Floods are also featured in numerous Native American tales, such as the Arapaho story of Creation, in which a man with a Flat Pipe enlists Turtle to help save the land or the Chickasaw Nation’s Legend of the Flood in which a raven delivers part of an ear of corn to a lone remaining family on a raft, post-Deluge.

|

| Hushpuppy faces an Auroch in Beasts of the Southern Wild |

In Beasts of the Southern Wild, the melting ice cap imagery is linked to the global warming rise of coastal waters — perhaps Earth’s way of punishing humankind (which could be seen as divine chastisement related to myths above). The “watery end of the world” theme, the motorboat as ark, the tavern as place of refuge, the release of supernatural beings (such as Hushpuppy’s vision of the frozen Aurochs unleashed through global warming), the connection to animals and earth as agents of healing (Hushpuppy listens to them): all of these elements in the film may be seen as related to flood myth tropes. Although there is no rainbow at the end, there is definitely as sense of renewal as Hushpuppy becomes the new Bathtub leader. The imagery and mythic tropes in the film overall resonate with symbols of giving birth: from the womb-like ark, to overwhelming water which could be seen as related to amniotic fluid, through Hushpuppy’s search for her long-absent mother.

With our collective experience of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and now Sandy in 2012, the poignant depiction of flood mythology tropes resonate strongly in this award-winning film. Watching Beasts of the Southern Wild allows us to consider the Deluge’s symbolic import to the human psyche not only as an image of destruction, but as an important signal of change, marking a time of transformation.

Guest post written by Ren Jender.

When the late Ed Koch, former mayor of New York City, saw How To Survive a Plague, journalist/director David France’s Oscar-nominated documentary about ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power) New York, he wrote a review for his local neighborhood newspaper. The review was not just a rave but recommended the activists profiled receive Presidential Medals of Freedom! Koch didn’t mention those same people and many others spent much time (including a demonstration documented at the beginning of the film) protesting his administration’s criminally inadequate response to the AIDS crisis. Some of the people he praised in his review, including one of the founders of ACT UP, Larry Kramer, have called him a “murderer.”

|

| Ed Koch image via Peter Staley, POZ Blogs |

Koch is an extreme example of the mainstream’s counterintuitive embrace of this film in particular and ACT UP in general. Although we see video of hateful, reactionary Jesse Helms spewing venom toward the group from the floor of the U.S. Senate we would never know most mainstream (and even some of the gay press’) coverage of ACT UP actions, like the one disrupting a service at St. Patrick’s Cathedral (to protest the Catholic Church’s stance on safer sex) or the one shutting down the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) — archival footage from both actions is part of the film– was far from laudatory.

Still, France’s overview, fortified by his work on AIDS issues in the gay press during the crisis years, is impressive even to those of us who were there. Though I never attended ACT UP meetings I took part in my city’s ACT UP demonstrations (“demos”), did safer sex outreach with ACT UP members and went to the huge Kennebunkport demo, shown in the film, where George H.W. Bush was hung in effigy.

|

| How to Survive a Plague |

Guest post written by Rosalind Kemp.

|

| Mads Mikkelsen as Johann Friedrich Struensee and Alicia Vikander as Queen Caroline Mathilde in A Royal Affair |

|

| Mikkel Boe Følsgaard as King Christian VII and Mads Mikkelsen Johann Friedrich Struensee in A Royal Affair |

A Royal Affair shows that sometimes friendship is more important than sex, which is refreshing for melodramas such as this, and that’s perhaps what makes it more disappointing when we see less of Caroline on-screen once her relationship with Struensee becomes sexual. She may discuss politics with him in her bed-chamber but when it comes to putting their ideas to council it has to be enacted by the men. There is no doubt that Caroline’s influence is powerful but it is so often behind the scenes, it’s pleasing in any case that her fascinating story has now been shown in film.

Guest post written by Natalie Wilson, originally published at Ms. Magazine. Cross-posted with permission.

Got a thing for zombies? Have some tween-age children in your life? Do you like whizz-bang stop-motion animation? Or, perhaps you are one of those types who appreciates a well-developed cast of characters that kicks stereotypes to the curb, features strong women and – can it be true?!?! – has a positively depicted openly gay character. If so, get thee to a theater and see the little-buzzed-about but much deserving ParaNorman–a zombie film not only with brains but a lot of heart.

|

| Norman Babcock and his family in ParaNorman | (L-R): Grandma Babcock (Elaine Stritch), Sandra (Leslie Mann), Perry (Jeff Garlin), Norman (Kodi Smit-McPhee), Courtney (Anna Kendrick) |

|

| Neil (Tucker Albrizzi) and Salma (Hanna Noyes) in ParaNorman |

|

| Emmanuelle Riva nominated for Amour |

|

| Naomi Watts nominated for The Impossible |

|

| Jessica Chastain nominated for Zero Dark Thirty |

|

| Jennifer Lawrence nominated for Silver Linings Playbook |

|

| Quvezhane Wallis nominated for Beasts of the Southern Wild |

|

| Hitchcock |

|

| Helen Mirren as Alma Reville (aka Lady Hitchcock), Anthony Hopkins as Hitchcock in Hitchcock |

Lines like that will undoubtedly give you a twinkle in your eye, since it’s easy to believe that Hitchcock the man might have had a fondness for perverse humor like that. But it just seems like lazy writing if you throw a couple of lines like that here and there when the rest of the film left much to be desired.

|

| (L-R): Jessica Biehl as Vera Miles, Scarlett Johansson as Janet Leigh, James D’Arcy as Anthony Perkins in Hitchcock |

|

| Galadriel (Cate Blanchett) in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey |

“… I am not a fan of Tarantino at all. At all. Generally, I find his work contrived, overly self-conscious, and, frankly, boring. Plus, to me he’s like the worst kind of hipster racist, a grown up version of Justin Timberlake desperately trying to affirm his black card at all times, while thoroughly proving himself to be white as hell…”

|

| Stephen (Samuel L. Jackson) and Broomhilda von Schaft (Kerry Washington) in Django Unchained |

“And if this dynamic is applicable anywhere in American history, it’s on a slave plantation. Frederick Douglass, in his slave narrative, traced his freedom not to the moment when he escaped to the north but the moment in which he first struck an overseer who attempted to whip him. Quentin Tarantino is the only filmmaker who could pack theatres with multiracial audiences eager to see a black hero murder a dizzying array of white slaveholders and overseers. (And, in all fairness, it’s not likely that a black director would’ve gotten a budget to even attempt such a thing.)”

|

| Django (Jamie Foxx) and Broomhilda von Schaft (Kerry Washington) in Django Unchained |