|

| Still from The Expendables 2 [source] |

|

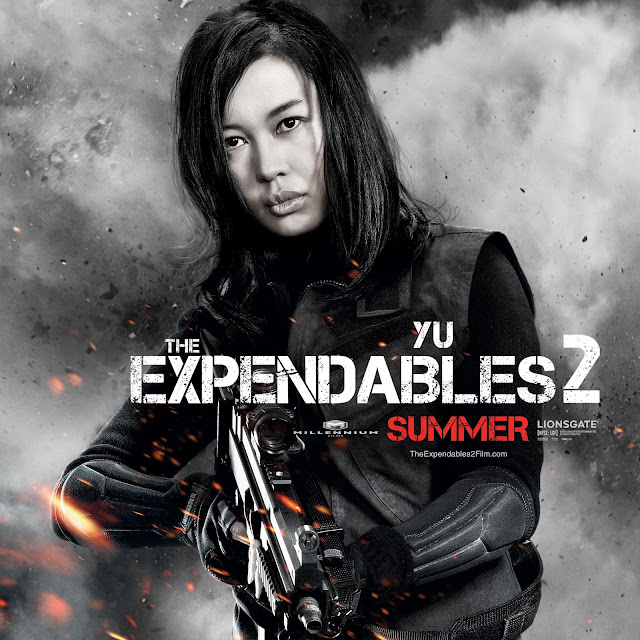

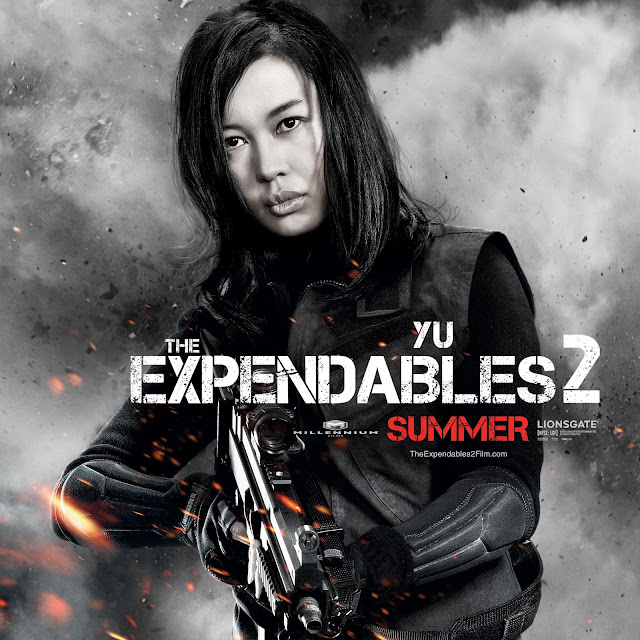

| Promotion poster for The Expendables 2 featuring Nan Yu |

The radical notion that women like good movies

|

| Still from The Expendables 2 [source] |

|

| Promotion poster for The Expendables 2 featuring Nan Yu |

|

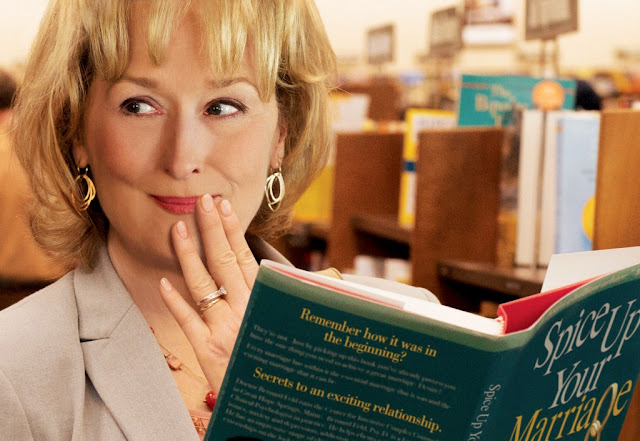

| Meryl Streep in Hope Springs |

Guest post written by Molly McCaffrey originally published at I Will Not Diet. Cross-posted with permission.

|

| Anne Hathaway as Catwoman in The Dark Knight Rises [source] |

While The Dark Knight Rises has had a more mixed reception than Christopher Nolan’s previous two entries in his Batman trilogy, everyone, even President Obama, can agree that Anne Hathaway’s Catwoman was the best thing about the movie. Slate’s Alyssa Rosenberg calls her, “the best Catwoman ever to grace the big screen.”

And I loved her too. The Dark Knight Rises‘s Selina Kyle is smart, sexy, and complex in her morality: the trinity of characteristics that unites all incarnations of Catwoman. The other details of Selina and her alter-ego Catwoman shift constantly (a fate common to comic book characters). She’s been an amnesiac flight attendant abuse victim (in the Gold and Silver Age comics in which she first appeared), a wealthy socialite who burgles for the thrill of the hunt (how she was portrayed in my introduction to the character, Batman: The Animated Series), a meek secretary transformed into a badass vigilante after her apparent murder by her powerful boss (in Batman Returns), and, well, whatever Halle Berry was reduced to doing with the character (who, just to be clear, was not Selina Kyle, but rather Patience Phillips, and I will waste no more words on a character and film that is best forgotten). As Rosenberg puts it in her Slate piece, “Catwoman has, in the past, been a rich well for explorations of female trauma.”

So it was inevitable that Selina Kyle be portrayed as a sex worker, at least once Frank Miller got his hands on her. Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy has always been transparently inspired by Miller’s seminal comics Batman: Year One and The Dark Knight Returns. The former series first introduced Selina Kyle as prostitute:

| Sex worker Selina Kyle in panels from Frank Miller’s Batman: Year One [source] |

And over the next twenty years or so of DC comics, the prostitute origin story would be hinted at, overtly dropped, slyly repackaged, forgotten, and popped back in at the whims of various comic book writers. Brian Cronin provides a thorough overview of the waxing and waning of this storyline in his Abandoned An’ Forsaked column. When it was announced that Hathaway had been cast as Selina Kyle in The Dark Knight Rises, speculation went wild regarding which Catwoman we’d get.

As it should be, The Dark Knight Rises offers a unique take on the character. And it stays cagey about her life’s details and origin story. But watching the film, I inferred that they were incorporating the sex worker background for the character. On the ride home from the theater I mentioned it to my husband, who is not a comic book reader, and he was bewildered how I had gotten that impression.

[SPOILERS for The Dark Knight Rises FORTHWITH]

As a comic book fan, I came in with the expectation that this movie’s version of Selina Kyle might be a sex worker. Because I knew Selina Kyle had been portrayed as one, most notably by Frank Miller, whose work has been so influential on the trilogy. So when Anne Hathaway’s Kyle seduces and absconds with a Congressperson (to provide herself with cover when she makes an illicit exchange, we discover) I figured she was doing this in the course of her business.

As that deal goes down, another character is introduced: Selina’s friend, played by Juno Temple, and according to IMDb named “Jen.” I don’t recall her being addressed by name in the film, but as soon as I saw her I thought to myself, “Oh, hey, it’s Holly Robinson!”

| Holly Robinson as drawn by Cameron Stewart in Catwoman Secret Files [source] |

Holly Robinson was created by Frank Miller in Batman: Year One, a fellow sex worker living with Selina Kyle. The appearance of that character, even though they’ve given her another name, signaled to me this character was meant to be in line with Miller’s Selina Kyle, a sex worker.

There’s also an offhand reference to Kyle living in “Old Town,” which I’ve never encountered in Batman comics (although there are many thousands I’ve never read, so maybe I am missing something) but which instantly called to mind the prostitute-run red light district of another Frank Miller comic, Sin City.

Selina Kyle’s primary motivation throughout The Dark Knight Rises is acquisition of the “Clean Slate,” a bit of technology that will erase her record, even her very existence, from the world’s databases, allowing her to escape an unspecified past where “she did what she had to do to survive.” Her past could be anything. It could merely be the thieving she’s clearly so adept at. But Kyle very pointedly shows no shame about her burgling, wearing Martha Wayne’s stolen string of pearls while dancing with Bruce at a gala, for example. It stands to reason there is something else she is running away from.

If you accept that The Dark Knight Rises‘s Kyle has a past or present as a sex worker, unfortunately the dynamic character seems much less innovative and much more like yet another iteration of the trope of the Hooker with the Heart of Gold.

The stock character of the Hooker with a Heart of Gold is problematic, even from a sex-work-positive feminist perspective, because the trope itself is not sex work positive. These characters are meant to be interesting because they are good “inside” even though they do “bad” things. The viewer is allowed to be titillated by the character’s occupation without needing to feel as though they condone it. And because hookers with hearts of gold are so often “saved” by men, it plays to a variety of male fantasies beyond women as commodities: that women need them; that women are “correctable.” The trope also reinforces traditional gender roles by masculinizing work for pay, often giving the hookers with hearts of gold tough, emotionally cool exteriors on the job (like men!) that when cracked (by a man!) show their soft, compassionate, womanly true self.

As we have with Selina Kyle in The Dark Knight Rises, who steals and betrays and displays a general disdain for everyone she speaks with in the first half of the movie (other than Holly Robinson’s stand-in). But somehow Batman cracks that ice, first getting Selina Kyle to display emotional vulnerability, and finally inspiring Catwoman to heroically help save the same Gotham she’d been keen to abandon after helping it fall to anarchy. When we spot her casually dining with Bruce Wayne in Florence at film’s end, it’s easy to imagine she’s given up her criminal ways: another soiled dove lifted to grace by a good man.

|

| Anne Hathaway as Catwoman, in hero-mode on the Bat Pod. [source] |

Even though I just wrote it, I find this summary of The Dark Knight Rises‘s arc for Selina Kyle overly reductive, and Anne Hathaway’s phenomenal performance in the role nuanced and charismatic enough that it elevates the material. Which is why I don’t so much object that The Dark Knight Rises invokes the trope of the Hooker with a Heart of Gold, I just mind that it does so covertly. It weakens the film’s ability to twist the trope and present a feminist take on it, and wastes an opportunity to give the world an iconic, heroic, feminist character who does or did sex work.

So it doesn’t bother me that The Dark Knight Rises possibly included sex work in the character background of its Catwoman, but it bothers me that they didn’t commit to it. The film signals dog whistles to comic book fans and enable the character and movie to enjoy all the male-id-pleasing benefits of the Hooker With a Heart of Gold trope, without actually having to go to all the trouble of crafting a modern and respectable portrayal of the sex industry in a major summer blockbuster. It’s lazy, even cowardly, and Catwoman, Anne Hathaway, and us movie-watchers all deserved better.

—

Robin Hitchcock is an American writer currently living in Cape Town, South Africa. She had to take the long way home for weeks while The Dark Knight Rises filmed in her neighborhood in Pittsburgh.

|

| Emma Stone as Gwen Stacy in The Amazing Spider-Man |

|

| Gwen in the hallway of Midtown Science High School |

|

| Gwen working at OsCorp |

|

| Gwen and Peter (Andrew Garfield) |

|

| Noomi Rapace as Dr. Elizabeth Shaw in Prometheus |

Guest post written by Rachel Redfern previously appeared at Bitch Flicks on June 20, 2012 and was originally published at Not Another Wave. Cross-posted with permission.

The prequel and spinoff for the classic film Alien has as much feminist food as its precursor did, albeit slightly less groundbreaking, though we can’t fault it for that: Alien did give us the first female action hero in Sigourney Weaver’s portrayal of the irrepressible Ripley.

|

| Noomi Rapace (Dr. Elizabeth Shaw) in Prometheus |

This post written by staff writer Megan Kearns originally appeared at Bitch Flicks on June 12, 2012.

[…]

[…]

|

This review by Editor and Co-Founder Amber Leab originally appeared at Bitch Flicks on August 30, 2010.

The plot of Inception is deceptively simple: a tale of corporate espionage sidetracked by a man’s obsession with his dead wife and complicated by groovy special effects and dream technology. As far as summer blockbusters and action/heist/corporate espionage movies go, it’s not bad. Once you get beyond the genuinely beautiful camera work and dizzying special effects, however, you’re not left with much.

One thing that really bothers me about the film–aside from its dull, lifeless, stereotypical, and utterly useless female characters (which I’ll get to in a moment)–is that nothing is at stake. Dom Cobb (Leo DiCaprio) and his team take on a big new job: one seemingly powerful businessman, Saito (Ken Watanabe), wants an idea planted into the mind of another powerful businessman, Robert Fischer (Cillian Murphy). Specifically, Saito wants Fischer to believe that dear old dad’s dying wish was for him to break up the family business, so that, we assume, Saito wins the game of capitalism. Should the team go through with the profitable job? We aren’t supposed to care about the answer to this question or what is at stake in the plot.

It’s assumed that, of course we want Cobb to win because he’s really Leo, and, you see, Leo is talented but Troubled. What troubles him? You guessed it: a woman. A woman whose very name–Mal (played by Marion Cotillard, an immensely talented actress who’s wasted in this role)–literally means “bad.” Who or what will rescue Cobb/Leo from his troubles? You guessed it again: a woman. This time, it’s a woman whose very name–Ariadne (played by Ellen Page in a way that demands absolutely no commentary)–means “utterly pure,” and who is younger, asexual (a counter to Mal’s dangerous French sexuality) and without any backstory or past of her own to smudge the movie’s–and her own–focus on Cobb/Leo. So, it’s not a stretch here to say that Cobb needs a pure woman to escape the bad one. Virgin/whore stereotype, anyone?

|

||

| Sarah Jessica Parker in I Don’t Know How She Does It |

Guest post written by Kim Cummings. Originally published at her blog Filmmaking, Motherhood and Apple Pie, cross-posted with permission.

|

| Sarah Jessica Parker and Pierce Brosnan in I Don’t Know How She Does It |

Guest post written by Laura A. Shamas. Originally published at Women and Hollywood, cross-posted with permission.

I have a confession to make. I’m a big softie when it comes to movies. I shed tears at the drop of a hat. But I usually don’t cry during a film trailer. But Beasts of the Southern Wild — both the trailer and the film itself — made me weep.

A strange, haunting, breathtaking dystopian fantasy — it contends with polar ice caps melting, prehistoric creatures, lands flooding, and the bonds of family. With its lush scenes, poignant and complex characters, and achingly beautiful music, it stirred emotions and memories long forgotten. It’s a triumph of the human spirit. And the best part? At the bittersweet film’s center is a little girl.

The film’s female protagonist is Hushpuppy, a 6-year-old African American girl who lives with her father on an island called the Bathtub. And she is a breath of fresh air. Played with depth, nuance and sensitivity, newcomer Quvenzhané Wallis — who’s already generating lots of Oscar buzz — dazzles on-screen. Her luminous personality captivating you at every moment. She’s been called “a miniature force of nature.” And I couldn’t think of a more perfect description. It’s hard to believe Wallis was only 5 years old when she filmed the movie.

Hushpuppy is a pint-sized powerhouse. An indomitable survivor. She’s brave, tough and strong-willed. There’s a fierce intensity, and an old wisdom behind her eyes. Honest, vulnerable and sweet – she is the film’s moral compass, its anchor.

Too often with films with daughters, they merely exist so we can see how the parents react to them. But here, we witness the story unfold from Hushpuppy’s perspective. Director and co-screenwriter Benh Zeitlin said he made a conscious decision to only yield information Hushpuppy has access to. We the audience see only what she sees. She narrates the film throughout so we always know her thoughts and feelings. But honestly, even if you erased all the narration, you would still know because of Wallis’ expressive face and body language. Through her narration, we peek a glimpse into her psyche. Hushpuppy utters poetic and sage musings:

“When it all goes quiet behind my eyes, I see everything that made me flying around in invisible pieces… Everybody loses the thing that made them. The brave men stay and watch it happen. They don’t run.”

“I see that I am a little piece of a big, big universe, and that makes it right.”

Hushpuppy frequently lets out this little scream that reminds me of a warrior cry akin to Xena. It’s as if she’s declaring, “I’m here world. Deal with it.” She carries the weight of the world on her shoulders. Yet there’s a buoyancy to her spirit. Putting animals up to her ear so she can “listen to their innermost desires,” savoring each bite of food she eats…these bring her joyous rapture. Hushpuppy is the film’s moral compass and anchor. We see the whole world through her eyes.

While at times it looks the same, the world in Beasts of the Southern Wild is not ours. The Bathtub was inspired by the real Louisiana island Isle de Jean Charles, which is frequently flooded and is “cut off from the levee system.” Beneath the surface of this strange fantasy, it feels like an allegory of Hurricane Katrina. Although director and screenwriter Zeitlin insists the film is not about Katrina. An apocalyptic fantasy grounded in realism, Zeitlin discussed the film’s message:

“It’s a folk tale about the emotional experience of what it’s like to have to survive the end of your world, and to lose the things that made you.”

Despite his protestations, the parallels between Beasts of the Southern Wild and Hurricane Katrina are uncanny. The film contends with how to survive losing your home amongst horrific destruction and how we shouldn’t turn our back on people. Again feeling like a parallel to the way the government turned its back on Katrina survivors, particularly the survivors of color. The film also contains a strong message of environmentalism. If we continue down the same path of environmental degradation, we may destroy the planet. The philosophy that we are all connected reverberates throughout the film. Especially when Hushpuppy says:

“The whole universe depends on everything fitting together just right. If one piece busts, even the smallest piece…the entire universe will get busted.”

Beasts of the Southern Wild features a disturbing yet loving relationship between Hushpuppy and her ailing father Wink (Dwight Henry), an alcoholic, who vacillates between joyful hope and pained anger. In the beginning, he’s cold and cruel, alcohol warping his lucidity and judgment. He knows he has to take care of her and teach her how to survive in the world. But he seems to resent it as he can barely take care of himself. We eventually see his benevolent streak as he looks for survivors. By the end of the film, I broke down in silent sobs as we witness the strength of their bond.

Too often in film and TV, black fathers are absent, either dead or incarcerated. So it was great that here was a black father. And Henry imbued depth, anger, pain and hope into his character. But why did he have to be so broken? Why can’t we see a positive representation of a black father?

Like many fantasies and fairy tales, we witness an absent mother. But Hushpuppy’s mother’s presence is very much alive. Hushpuppy carries around a sports jersey, a symbol of her mother. She has imaginary conversations with her mother. When she sees a blinking beacon off on the horizon, she believes it’s her mother beckoning her. We also see a maternal figure in Miss Bathsheeba (Gina Montana) who nurtures and cares for all the children of the Bathtub. As her world begins to crumble, Hushpuppy eventually goes in search of her mother. In her journey, Hushpuppy traverses the land with three young girls at her side.

The film boasts strong, resilient, outspoken women and girls. And the stereotypically feminine trait of caretaking is lauded and celebrated. Miss Bathsheeba tells the children that they’ve got to take care for those “littler and sweeter than them…that’s the most important lesson I can teach you.” Wink believes it’s his duty and responsibility to teach his daughter how to survive and take care of herself. Screenwriter Lucy Alibar said he ultimately teaches Hushpuppy:

“How to take care of people. How to take care of someone weaker than you. The strength of kindness. The strength of standing with some place, with your family.”

Sadly, through gendered language, the feminine is often denigrated and demeaned at worst and diminished at best.

Wink often says “man” to Hushpuppy, like “Hey, man.” When they arm wrestle he asks her, “Who’s the man?” To which she proudly replies, “I’m the man.” When Hushpuppy’s house is destroyed – yes, her and her father each have their own house with their own belongings – he draws a line separating Hushpuppy from his sphere, the masculine one. He tells her that no girly toys are allowed on his side, but that he can’t hit her on her own side, something in her favor (Um, what?? Yeah, I’m not cool with violence). Wink often tells Hushpuppy, “No crying,” not allowing her emotions that depict weakness in his eyes. Even when we’re introduced to Miss Bathsheeba (Gina Watson), she’s telling the children not to be “pussies,” something uttered by Hushpuppy herself later in the film.

Food plays an integral role in the film, as sustenance, as a part of culture and as celebration. You see Hushpuppy, her father and their community eating seafood. While it was difficult for me to watch as a vegan, the feminist in me was thrilled that we see a girl eat. In reality, women and girls obviously eat. Due to the media’s policing of female bodies, women and girls have an antagonistic relationship to food. We don’t typically see female characters eating on-screen.

We also see a subtle commentary on gender performance and gender norms. When the residents of the Bathtub are transported to the mainland by the government, Hushpuppy is forced to wear a frilly, girlie-girl dress and tame her wild hair. Stripped of her identity and forced into conformity, she looks miserable. She doesn’t want to be constrained in gender stereotypes. Unconsciously, she wants to perform gender on her terms, not society’s.

I often lament the lack of female-centric films, particularly with women and girls of color. When we do see women, they usually appear as sidekicks or love interests to men. But not here. A black girl is front and center. And even though the film focuses on Hushpuppy’s relationship with her father, her relationship with her mother is equally as important.

We often see boys and men in films that showcase a hero’s journey or transformation. But here – in this film showcasing a triumph of the spirit – we see a journey with a strong-willed, opinionated girl of color. And I couldn’t be more thrilled.

Mystical, ethereal, surreal, touching – Beasts of the Southern Wild is all of these and yet so much more. Even as you watch the film, you might not understand or fully comprehend the meaning of the unusual plot. But let its poetic beauty, emotions and raw honesty wash over you. Let it sink in. For it will be a long time before another film like it – or another female hero as complex as Hushpuppy – comes our way.