|

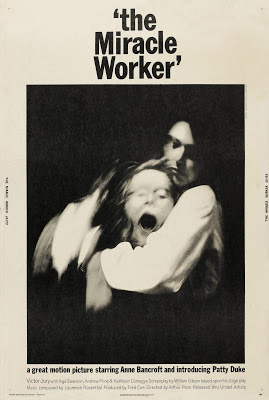

| The Miracle Worker film poster. |

The Miracle Worker summarizes the turbulent beginnings of one of the most remarkably profound relationships in history–Anne Sullivan and her pupil/mentee Helen Keller. Various films have been made about this duo, but nothing quite compares to the original 1962 adaptation of William Gibson’s stage play. Both Broadway actresses, Anne Bancroft and Patty Duke, reprise their respective lead roles as Anne Sullivan and Helen Keller.

The first scene ends on Kate Keller screaming in outlandish revulsion at the shocking discovery of having a blind daughter, as though the crib contained a grisly, terrifying monster straight out of her nightmares. Helen’s discrepancies are depicted in extreme exaggeration on the film poster–an open mouth on blurred face looking possessed by devil’s agony while a calm, serene woman holds her steady, showcasing psychological depth rather than horror thriller.

|

| Helen’s parents spoil instead of nurture–Captain Arthur Keller (Victor Rory) and Kate Keller (Inga Swenson). |

Years pass by and despite being rich, slave-owning Southerners, the Kellers have searched far and wide for solutions in curing their deaf, blind and mute child. The family has somewhat accepted Helen, coddling her ignorance. They hover and pet her like a wild animal, but do not educate further while Helen desires to learn and comprehend the world around her.

“Put her in an insane asylum!” protests Jimmy, Helen’s half brother, after Helen accidentally knocks down the baby’s crib–with baby still inside.

It is easy to place an incomprehensible diagnosis inside a box and throw away logic. Back in the turn of 19th century, people of Helen’s delicate condition would have been sentenced inside “madhouses” because no one knew how to communicate with them or even try. Jimmy is oblivious in seeing that Helen’s manic outbursts are not signs of mental disorder. Helen’s incoherent mumbles, cries, and physical punches stem from frustrations of an isolated mind desiring to learn how to address humankind–not doctors, needles, and shock therapy. It doesn’t help that Kate wants to keep Helen just to baby her and Captain Keller simply obliges Kate’s wishes to have their daughter close. They love her, but none of them realize what Helen sincerely needs.

Helen has a mind dying to be nurtured, but the Kellers don’t know to broaden her horizons.

|

| Helen (Patty Duke) explores Anne’s (Anne Bancroft) suitcase. |

In comes Anne Sullivan the answer to their troubles. She is a freshly graduated valedictorian tormented by events of a troubling past. She often remembers desiring to learn amongst strict caretakers who believed her incapable due to blindness. That lifelong quest for knowledge is a trait companionable to Helen’s silent plight. When Anne greets her young protégé on the porch, Helen immediately touches both Anne’s suitcase and her face, feeling Anne’s entire structures with curiously wandering hands, knowing instantly that she is a new person. Helen picks up the suitcase, slaps Anne who tries taking it away, and takes her suitcase inside house and up the stairs–signs of both kindness and gracious hospitality. Helen’s joy slips away suddenly at Anne’s stern ways of teachings, in a stricter fashion than Helen is unused to. The angry, spoiled child locks Anne into her room and hides the key, revealing a sneaky intelligence and fiery spirit.

Captain Keller, however, is displeased with Anne’s age and appearance, especially her rounded black spectacles.

“Why does she wear those glasses?” Captain Keller asks.

“She had nine operations on her eyes,” Kate says. “One just before she left.”

“Blind! Good heavens! They expect one blind child to teach another?” He asks, very disapproved. “Even a house full of grown adults can’t cope with a child. How can an inexperienced half blind Yankee school girl manage?”

|

| Anne (Anne Bancroft) and Helen (Patty Duke). |

Anne manages, and she manages well.

In the breakfast scene of severe sound and action, in moments of brutally charged, disturbing pandemonium, Anne single-handedly demonstrates powerful mastery over Helen’s wildly aggressive tendencies by battling fire with fire instead of pampering her. Anne is trying desperately to get Helen to eat with a spoon instead of the barbaric, uncivilized audacity to eat off her family’s plates with bare hands. Helen bites, slaps, spits, and bangs on locked doors, fighting stubbornly against new lessons, but Anne is forceful and undeterred, pushing Helen into unlearning childish behavior. Glasses shatter and food is spilled everywhere, but Anne has made an alarming advancement.

“The room is a wreck but her napkin is folded,” she reveals to Kate.

Kate beams with pure joy at this statement, but Captain Keller doesn’t see why.

“What in heaven’s name is so extraordinary about folding a napkin?” He asks.

“It’s more than you’ve ever done,” Kate replies.

|

| The real life Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan. |

Men appear to be damaging catalysts–undermining Anne’s progress in every which way since she arrived. From first appearances alone, Captain Keller believes Anne to be young and inept, but after giving her a chance to prove diligence he wants to fire her because she’s not docile and kind like fair sex allots. In fact, she tells him what to do on many occasions and it infuriates him. On the other hand, Jimmy wants Anne to give up and see that Helen is a creature that needs pity, but with being typical male, in the same breath he also says, “You could be handsome if it weren’t for your eye.” These two characters appear to be more angered by the fact that she’s a woman and that threatens their authority. Captain Keller just wants another instructor while Jimmy still insists that Helen be institutionalized.

However, Anne sees the true thorn in the Keller household and it’s not just the men making circumstances problematic.

|

| Slowly Helen (Patty Duke) is learning from Anne’s (Anne Bancroft) unorthodox methods. |

“Mrs. Keller, I don’t think Helen’s greatest handicap is deafness or blindness,” Anne reveals to Kate, her devout champion. “I think it’s your love and pity. All these years you’ve felt so sorry for her you’ve kept her like a pet. Well, even a dog you housebreak.”

Surprisingly, she doesn’t include the hired help. Although slavery has been abolished (15 years before Helen was born), they too are considered lower housebroken beings, hardworking “dogs” that labor for the wealthy family. They don’t get the same favorable treatment as Helen due to their skin color and a cruelly unjust class system. When Anne forces a black child to get up out of bed and factors him into her lessons with Helen, he winces in fright. This demonstrates that the child is expendable and however much Helen hurts him, no one would care.

Anne gets permission to teach Helen for two weeks outside of Keller custody. Helen is upset to be alone with her, but in a couple of days, Anne’s instructions and experiences start sinking in as well as emotional components of joy, excitement, and humor. Manic episodes diminish slowly and engaging happiness brightens Helen’s once timid disposition.

|

| Helen’s (Patty Duke) remarkable breakthrough of water thanks to Anne (Anne Bancroft). |

Unfortunately, Kate doesn’t agree with Anne’s need for more time alone with Helen, claiming to miss her daughter and saying that obedience is enough. It’s off-putting. Anne wants to teach Helen, but iron gates have once again been placed around Helen as though she were a living doll to adore and not a person worthy of truly learning about words and meanings behind them.

Back at home, Helen is determined to revert back to her old ways, but Anne wants her not to forget all that she has taught and thanks to Jimmy’s surprising aid she does just that. It is just as she is refilling the pitcher, water covering her hands, that Helen makes a most impressive breakthrough.

“She knows!” Anne shouts joyously.

And in a bittersweet exchange, towards the end in an utterly touching display of symbolic affection, Helen finally gives Anne back the key to her locked room.

The Miracle Worker is a wonderful portrayal of two strong women, and Bancroft and Duke won Academy Awards for their leading and supportive roles. Anne and Helen impacted the world by not letting blindness or deafness confine them into a shelled prison sentence. They relied solely on one another. Partly due to Anne’s vigorous aide, Helen–a writer, activist and lecturer–went on to become the first deaf blind person to earn a bachelor’s degree. Together Anne and Helen used these unique circumstances as stepping stones toward helping others find their worthiness, showing that though the world appears black and soundless, this is not a hindrance or burden.

|

| Helen (Patty Duke) touches her parents (Victor Fury and Inga Swenson) in a beguiling discovery. |

Their friendship may have faced tempestuous struggle and staggering barriers, but Anne Sullivan and Helen Keller concluded 40 years of camaraderie with compelling milestones that continue to be worth honoring today.