This is a guest post by Josh Ralske.

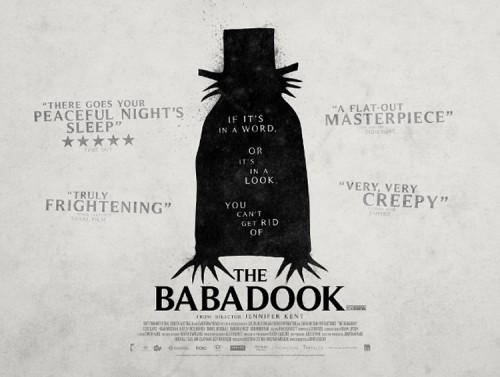

Australian writer-director Jennifer Kent’s feature debut The Babadook is the surprise hit horror film of the year. (Read Sarah Smyth’s review here.) With no stars and a limited budget, Kent cannily tells the story of Amelia (Essie Davis), a widow still wracked with grief over the death of her husband six years earlier, and Amelia’s troubled young son Samuel (Noah Wiseman), whose obsessive fear of monsters verges on the manic. One night, Samuel pulls an unfamiliar book from the shelf for his mother to read to him, Mr. Babadook. Amelia reads the book, unleashing the titular monster into their home. The mother and son, and the movie, increasingly retreat into their own horrific private world, terrorized by a fairy tale-like creature that seems intent on driving Amelia into madness.

The narrative is simple, and pointedly familiar, but The Babadook is notable for the complexity of its two main characters, and the remarkable performances that bring them to such vivid life.

We spoke with Kent on the phone about the film’s creation and its success.

Bitch Flicks: Congratulations on all the acclaim that the film is getting.

Jennifer Kent: Thank you. It’s been a real trip. It’s been a long and fantastic journey for this film. It’s been amazing.

BF: How did you get the idea for the film? Are you a parent yourself?

JK: No. No, I’m not. Obviously the mother/child relationship is really important in the film, but what i was really focused on was her, on this woman and her suppression of something she found impossible to face. That was the starting point for me. I feel if you suppress things in life, you don’t just affect yourself; you affect everyone around you. So then the choice to have that little boy in the picture, and to make him a kind of mirror to her was how it worked out. But it wasn’t, for me, entirely a story about motherhood, although that is a really important factor in the film.

BF: I understand what you’re saying about it being a very personal story, and starting with Amelia’s character, and what’s refreshing about it is how complex her character is. She isn’t just one thing. She’s not the type of female protagonist that you see in a typical horror film.

JK: I didn’t start with motherhood being the primary focus, but it is a very important part of the film, and I’m very adamant not to make this woman the evil mother. That’s why I placed the film very much inside her experience. Even when the shit hits the fan later in the film, we’re still experiencing it largely from her perspective, and I wanted her to be complex. She’s trying so hard. She’s a loving person. She’s drowning. She’s a drowning woman in this situation, but she wants to do the right thing, and I was interested in exploring that. I’m the type of person, when I read or hear about these parents killing or harming their kids… Of course it’s a tragedy, and the act of those parents is abominable, but they’re not monsters. They’re human beings. And my empathy and my sensitivity around these things made me curious. How does one get to that place where they become this monstrous mother? How does that happen? And so that’s why, I guess, I feel proud of that character, of Amelia. No one’s saying that she’s a one note character.

BF: Your empathy for the character really comes through. Could you talk a little bit about casting Samuel, and your conception of that character, because again, it’s not a child character that I’ve seen in any other film. He’s a very unique movie kid.

JK: Yeah. If you met [Noah], you’d be shocked, because he’s the opposite of Sam. He’s very quiet and sweet. That’s all acting. And he is an empathetic kid. He really loved Sam. He really felt sorry for Sam, because his mom wouldn’t listen to him. And he was right. And I think the quality that I was looking for in the little boy who would play Sam was that empathy. And of course, Sam’s a strange kid, and very annoying at times, but ultimately, he loves his mom and he wants to protect her. So I needed a child who could embody all those qualities. And someone who could be directed. A lot of kids that come into these auditions, they’re like machines. But they can’t necessarily change and give you a subtle performance. But Noah could, and the key to that for me was improvisation. So we played games and we imagined things with the boys who got down to the final short list. And Noah was a standout in that way: vivid imagination, very emotionally intelligent. And robust. You know, I didn’t want a kid that was going to collapse on the second day of shooting, saying “I wanna go home.” He was there for the six weeks of shooting, day in and day out, and when I think about what he did, it’s an extraordinary thing for a 6-year-old to achieve.

BF: Yeah, that’s amazing. I didn’t know if you’d found a kid who was just sort of like that, or if you’d found someone capable of bringing that character to life without necessarily being that way. That’s interesting.

JK: Yeah, he was really fun and sweet. And in fact, one interesting thing about that process is that kids don’t want to be disobedient, so it was really hard to get him to be that way in rehearsals. I had to give him permission to be naughty, because yeah, kids are socialized — unless they’re brought up badly — to be well-behaved. So yeah, it was a real process for him.

BF: Did you set out to make a horror film? Is that a genre that you’re interested in generally? I noticed the clips from Black Sabbath and House of Exorcism and of course, all those great George Méliès clips that Amelia sees on TV. Is that the type of work that drew you to this type of story?

JK: Yeah. I mean, I love horror. I love it! I even will see most of the modern stuff, and I always hope it’s gonna be good. But I definitely have watched a lot of Italian horror, lot of everything. So it’s in me. It’s in my DNA, but it isn’t the thing that rules me. And I have to say… I can’t speak for other filmmakers, but I imagine it wasn’t something that ruled them either. They start with an idea and a story and that’s what happens. I think there’s a danger in becoming subservient to a genre, going “Oh, I’m going to make a movie that’s going to scare everyone.” I needed to look deeper than that, and that’s why… It’s such an interesting thing, how bad horror can be, and I think when it’s really bad, it’s just made by people who don’t get it. Who don’t understand how powerful it is. You can really discuss deep issues with horror, in a way you can’t through drama. It’s one of the most cinematic genres as well, because it’s very closely linked with dreams. So yeah, I’m a fan.

BF: I agree with you that you can touch on these deep human issue through the genre. It doesn’t just have to be about saying “boo.” Amelia’s grief in the film is such a powerful thing that seems to be the genesis…

JK: Yeah. How would you discover that in drama? It would be very hard to not make it melodramatic. To put it in this realm actually makes people feel what Amelia’s feeling, on some level, and have empathy with her. I’ve noticed that the film doesn’t work with people who have low empathy [laughs] as human beings. It’s not a film for them. The people who it scares have more of that going on in their systems.

BF: Well, I liked it. I thought it was scary. So, I guess I check out on the empathy scale.

JK: So you’re a decent human being. [laughs]

BF: Yeah, I guess. If that’s your barometer for that. It’s really interesting to me. It has these very classical elements to it with the sense of isolation and the darkness and the way the Babadook himself is portrayed. There’s an old-fashioned quality to it. Could you talk about how you decided to visualize this monster?

JK: It was something that just felt right, this kind of childlike world. I’m really drawn to myths, and I guess I wanted to create a new myth in a domestic setting. Old children’s books, old fairy tales — you know, the brutal ones, the real ones — they touch on something very primal. They look childlike and innocuous, but deep down, there’s something really savage and sinister there. So that was my starting point for the world of the film. The book is obviously a very important part of it, so I wanted the Babadook to spring from the book, in terms of its style as well. And there’s something about the old horror that is very childlike, because it’s done in what we would consider now a very simple way, all in-camera techniques, but there’s something still very powerful about that, I think. Sometimes even more powerful than CGI and a lot of complicated post-production work. When something happens in camera, and you’re seeing it with the naked eye, you feel — I feel, anyway — differently. It feels like it’s happening there and it’s more real to me.

BF: I think it’s very effective, and it is an extension of the book in a way that works really well. Could you talk about the book itself? It was great. Very memorable, very vivid work that Alex Juhasz did.

JK: We looked for ages for an artist. We looked at lots of Australian illustrators, and we even worked with a couple in developing the Babadook look, but Alex was unique in that he’s actually an American artist. I saw his work and it was beautiful but really strange. I was drawn to him and his work. He has this thing of being able to keep his work original, but also took direction. So we were able to develop the look of the creature according to how I needed it to operate. So it wasn’t just finding an illustrator to make these beautiful pictures. He really understood the need for it to support the story. He was a good storyteller. And he also had a lot of work in stop motion animation. He designed the opening credits for United States of Tara, and he’d worked a lot with Jamie Caliri, the stop motion animator who did Lemony Snicket‘s end credits. He had a lot of experience that proved invaluable when it came to animating the book. He’s a bit of a genius, Alex.

BF: The illustrations themselves really set the tone for what’s to come.

JK: They come to life, so they needed to be energetic and have an ambitiousness to them.

BF: For women filmmakers, in the states at least, it can be particularly challenging to get a first film made and shown. Is that something you want to address?

JK: I’m not so much aware. I don’t think of myself — I know I’m a woman, of course, but I don’t feel ruled by it. I think a film is hard to make, full stop. I think a person’s first feature is a real trial by fire, no matter if you’re male, female, or otherwise, and it’s not something that I feel really informed me. It certainly didn’t hinder me. Not in Australia, anyway. And I must say, I’ve had a lot of meetings with various people in America since Babadook premiered in Sundance, and admittedly, I haven’t done any work there yet, but I’ve never felt encumbered or restrained by my gender in that context. I’m not saying sexism doesn’t exist, but I don’t give it much time. I’ve got too much to do.

BF: Do you think, though, that — I don’t know, that scene where Amelia is using the vibrator… I’m not sure there are many male filmmakers that would’ve thought to include a scene like that, but it’s an important scene in terms of understanding who Amelia is and what she’s dealing with.

JK: My gaze and my way of looking at the world is inherently feminine, from a feminine perspective, and there are things in that film that probably wouldn’t be written by a male writer. But I don’t know. Isn’t that the way with all films? They come from the person who makes them. I understand what you’re saying, Josh, I’m just trying to… it’s a complex issue. Yes, there’s sexism in the world and there’s an incredible imbalance of males to females represented in all films. Most films are about male stories. So yeah, maybe I just put a female story out there, and the fact that it’s unique says that we still have a long way to go in terms of making more female stories come to life. I hope I can put a few more out there. Female stories with women at their core.

BF: Me, too. Congratulations on this film. It’s very effective and well done. Do you know what your next project is going to be yet?

JK: I’ve got two films I’m working on, and I’ve come back from America with about 25 scripts to read, so I’ll be plowing through them. And it looks like I’m going to jump onto a TV series, to write and direct in America. A miniseries, but that hasn’t been announced, so I’m hesitant to talk about it. A lot of opportunities have come up. I’m in a very fortunate position at the moment, and hopefully we’ll be making something sooner rather than later.

BF: I’m looking forward to seeing what you do next. Thanks a lot for taking the time to speak with me.

Josh Ralske is a freelance film writer based in New York. He has written for MovieMaker Magazine and All Movie Guide.