This guest post by Emma Houxbois appears as part of our theme week on The Female Gaze.

“You guys know about vampires?” author Junot Diaz once asked an audience of college students. “You know, vampires have no reflections in a mirror? There’s this idea that monsters don’t have reflections in a mirror. And what I’ve always thought isn’t that monsters don’t have reflections in a mirror. It’s that if you want to make a human being into a monster, deny them, at the cultural level, any reflection of themselves. And growing up, I felt like a monster in some ways. I didn’t see myself reflected at all. I was like, ‘Yo, is something wrong with me? That the whole society seems to think that people like me don’t exist?'”

This is the starting point of Blue is the Warmest Color, which contends, and grapples with, the fact that depictions of female pleasure by female artists do not exist in art. This condition, this lack of understanding and representation, is what dogs its protagonist, Adele, as she struggles and ultimately fails to achieve a sense of comfort with her queerness. Female pleasure abounds in the film from the explicit sex between Adele and Emma, whose romance the film charts the rise and fall of, to eating, and the particular pleasure of observing and being observed. Adele is sometimes the subject, as she pursues Emma or when they take in an art exhibit, her gaze on the nude female figures constructed by men the focus of the scene, and sometimes she is the object as she poses for Emma’s paintings, the first representational work of her lover’s career.

The English title of the film, the same as the graphic novel it was adapted from, implies an inversion of the normal way of seeing. We’re used to seeing blue as cool, cold, and distant, but the film challenges us to see it as a vibrant and passionate colour the way that it challenges us to reconceptualize the power and passion of queer love. The French title, La Vie D’Adele: Chapitres I & II are heavy with film and literary allusions. To The Story of Adele H, the loose account of how Victor Hugo’s daughter pursued an unrequited love across continents and La Vie de Marianne, a novel left unfinished, suggesting both tragedy and an unfinished quality, which both come into fruition. Adele remains restless and unfulfilled throughout the film as Truffaut’s depiction of Adele Hugo is, but the irony of the reference is that Blue’s Adele is an inversion. Instead of warping the world around her to believe that an unrequited love is genuine, Adele is dogged by the invisible weight of heteronormativity that propels her to hide her relationship and live in a private shame. The female gaze, such as it exists in a world that denies its existence, is an insular one that exists between Adele and Emma as opposed to how the film itself is shot. The film presents the case for the female gaze by examining what happens when it’s withheld.

The problem with the male gaze and trying to uplift or separate a female equivalent from it is that male gaze as a term and concept has shrunk in its application to a narrow didactic interpretation that borders on being universally pejorative. To wit, the simple unexamined usage of the term was thought to be all that was needed to condemn Blue is the Warmest Color by its skeptics, but the use of “male gaze” as a cudgel that immediately translates into prurience and exploitation does more harm than good to the conception of a female gaze not least because it immediately valorizes the alternative, as elaborated on by Edward Snow in his essay “Theorizing the Male Gaze: Some Problems”:

“Nothing could better serve the paternal superego than to reduce masculine vision completely to the terms of power, violence, and control, to make disappear whatever in the male gaze remains outside the patriarchal, and pronounce outlawed, guilty, damaging, and illicitly possessive every male view of women. It is precisely on such grounds that the father’s law institutes and maintains itself in vision. A feminism not attuned to internal difference risks becoming the instrument rather than the abrogator of the law.

[…]

Under the aegis of demystifying and excoriating male vision, the critic systematically deprives images of women of their subjective or undecidable aspects- to say nothing of their power -and at the same time eliminates from the onlooking “male” ego whatever elements of identification with, sympathy for, or vulnerability to the feminine such images bespeak.”

Simply put, the male gaze is not a monolith, and despite the way that the term is used in criticism and conversation, no one actually views film from the position that the male gaze is monolithic or purely informed by patriarchal values. To actually adopt that stance would require the conflation of Kenneth Anger with Quentin Tarantino, among other laughable absurdities. Male-directed film has always found ways to appeal to women on terms other than internalized misogyny, and of course the male vision in film has been frequently mitigated, influenced, or redirected by the work of women in other roles. Tarantino, for instance, is famous for his collaboration with the late editor Sally Menke, whom he sought out specifically for a feminine influence, which is hardly a rare event. Much recent buzz was generated by another female editor, Margaret Sixel, who worked on Mad Max: Fury Road with longtime collaborator George Miller (she edited Happy Feet and Babe: Pig in the City for him). Her contribution has been argued as being integral to the strong female reception to the movie, which, again, runs the risk of valorizing women’s work as being inherently superior.

The problem with strictly gendering the gaze is that it can improperly frame collaborations and essentialize the vision of female filmmakers. Mad Max: Fury Road, as a film, is more than the sum of a male director and a female editor, especially for a narrative so committed to dissecting toxic masculinity from within. So too ought Sally Menke’s work with Tarantino be seen more than just a mitigation, but a cornerstone of Tarantino’s desire to achieve more that what the limitations of his masculinity allow for, especially as the roles of women in his films evolved from non existent in Reservoir Dogs to the complete focus in Deathproof. Perhaps the most intriguing recent example of how a female collaborator transformed the work of a male director was in Gillian Flynn’s adaptation of her own novel Gone Girl for David Fincher, inverting the uncomfortable and frequently malicious male gaze that engenders his work, transferring the web of fear that his female protagonists like The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo’s Lisbeth Salander or Alien 3’s Ripley live in to the male protagonist and through him, the male audience. It’s a synthesis that cannot be easily essentialized into a single gendered gaze.

This is compounded by the fact that male nor female are fixed categories, nor are their desires. How are we, for instance, intended to properly frame the work of Lana Wachowski as a trans woman? How trans women engage with gender in our own lives and through our art cannot and should not be subsumed into a lens defined by the cisgender female experience. Which is only the beginning of how ruinous categorizations of gender in the gaze are on queer film and filmmakers. In comic book criticism especially, lenses of queer male masculinity are frequently co-opted and assimilated into constructions of the female gaze, which has the twin repercussions of narrowing queer male desire to a pinprick of feminized male figures and completely alienating queer female desire. If there are to be productive critical frameworks that utilize “male” and “female” gazes, they must be understood as needing a prism held up to them in order to properly understand the full spectrum of what informs a particular vision. There needs to be an understanding of intersectionality intrinsic to their uses.

On that note, Adele Exarchopoulos and Lea Seydoux, the stars of Blue is the Warmest Color, are the only actors to have been awarded Cannes’ Palme D’Or alongside their director, Abdellatif Kechiche. It was done by a jury made up of Steven Spielberg, Bollywood actress Vidya Balan, Christoph Waltz, We Need To Talk About Kevin screenwriter Lynne Ramsay, Romanian writer-director Cristian Mungiu (whose Beyond the Hills and 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days have tackled themes including queer femininity and access to abortion), Japanese writer-director Naomi Kawase, Nicole Kidman, and Ang Lee. Nicole Kidman, it must be recalled, co-starred in Stanley Kubrick’s erotically charged Eyes Wide Shut with then husband Tom Cruise. Ang Lee’s career as a director has been built almost entirely out of critically lauded portrayals of queerness and eroticism including The Ice Storm; Lust, Caution; Brokeback Mountain; and Taking Woodstock. The crowning of Kechiche, Exarchopoulos, and Seydoux by this jury, Lee and Kidman in particular, ought to have carried with it all the mythic importance of Quentin Tarantino, as head jurist, awarding Chan-Wook Park the Palme D’Or for Oldboy a decade earlier. Instead it’s treated as a footnote. Presumably because in this instance, that jury was more attuned to the nuances of the male gaze than the American critical establishment that presaged its arrival on US soil with cries of exploitation and misogyny.

The Cannes jury made it clear that they wanted to define the film as a collaboration, and I would extend that further to define it as a conversation. At its heart, Blue is the Warmest Color is a film about performances of identity and how the stresses of assimilation can erode and destroy fundamental parts of our being. One of the primary ways that we can perceive Kechiche’s self awareness that his masculinity limits his ability to conceive of and portray female queerness accurately is the insertion of a viewpoint character for him, an Arab actor Adele originally meets at a party thrown for Emma’s artist friends. He asks naive, well meaning questions about their relationship that queer women the world over hear, but understanding that he’s probed far enough or perhaps too far into her life and identity as an interloper, he opens up to her. He tells her about how he’s an actor and he’s just been to the United States, describing New York City in the same way that we dreamily describe Paris. “They love it when we say Allahu Akbar,” he says with a smile, telling her about how there’s always a hunger for Arab terrorists in Hollywood. Kechiche is, himself, Tunisian, and this is his exegesis.

He’s approaching the queer experience from the perspective of the immigrant experience. This is the Adam’s Rib that he proffers up towards the goal of uncovering female pleasure in art. This is the part of himself that he bares in order to justify the depth with which he probes Adele and Emma’s relationship. The clearest way that we see his Arab identity in the film is in the act of cooking and eating, which easily transcends the specific cultural context he takes it from thanks to the intimacy and care with which it’s handled. Cooking is framed as emotional labor, seen most keenly as Adele frets over making Spaghetti Bolognese for Emma’s friends, fretting over it as she serves it. Eating is, except for Adele’s junk food stash, a communal act, the consumption of the emotional labour of cooking as much as the food itself. This merges with queerness as Adele tries oysters, possibly the most yonic food imaginable, at dinner with Emma’s family. Her hesitance and discomfiture with eating oysters despite the welcoming attitude of Emma’s family mirrors the overwhelming tension she’s experiencing in her performance of queer femininity, and the difficulty she’s experiencing in how accepting Emma’s family is of it.

The broader sense of how Kechiche attempts to conceive of queerness through the best available lens at his disposal is how he constructs France’s queer community as a diaspora. He portrays Adele’s budding queerness and her experience of the queer nightlife in much the same way as the child of immigrants might feel overwhelmed and illegitimate by their first exposure to their parents’ native culture. There are certainly parallels between Adele’s entry into the queer community while still in high school and A Prophet’s Malik’s early uncomfortable interactions with the Arab prisoners after having been forcibly assimilated into the ranks of the Corsicans.

Where they differ is that Malik is able to thrive within the group by shedding attachments to the structures that will never accept him while Adele folds under the pressure of maintaining both a queer identity and the public performance of a straight one, immolating her relationship with Emma and leaving her isolated. Similarly, the Arab character returns to the film as Adele visits Emma’s latest show after their reconciliation. He tells her that he’s left acting, that he got tired of that one narrow performance of identity that the film industry allowed him. He’s never been happier. Adele remains unable to shed that attachment to the normative world and leaves feeling more upset and isolated than ever before.

The pressure of assimilation asserted by heteronormativity and white supremacy are distinct yet similarly functioning forces, which is one of the main achievements of the film. While it is by definition an uneasy attempt at capturing the queer female condition, Blue is the Warmest Color succeeds magnificently by providing a context and a shared struggle with which to build solidarity between marginalized groups in contemporary France. In the scene immediately following Adele’s break up with Emma, we see her leading her children in a celebration of African culture, with Adele wearing a cheaply thrown together pastiche of African fashion, adopting a clearly false and ill fitting identity. It’s a stark metaphor for how poorly Adele assimilates into heteronormativity.

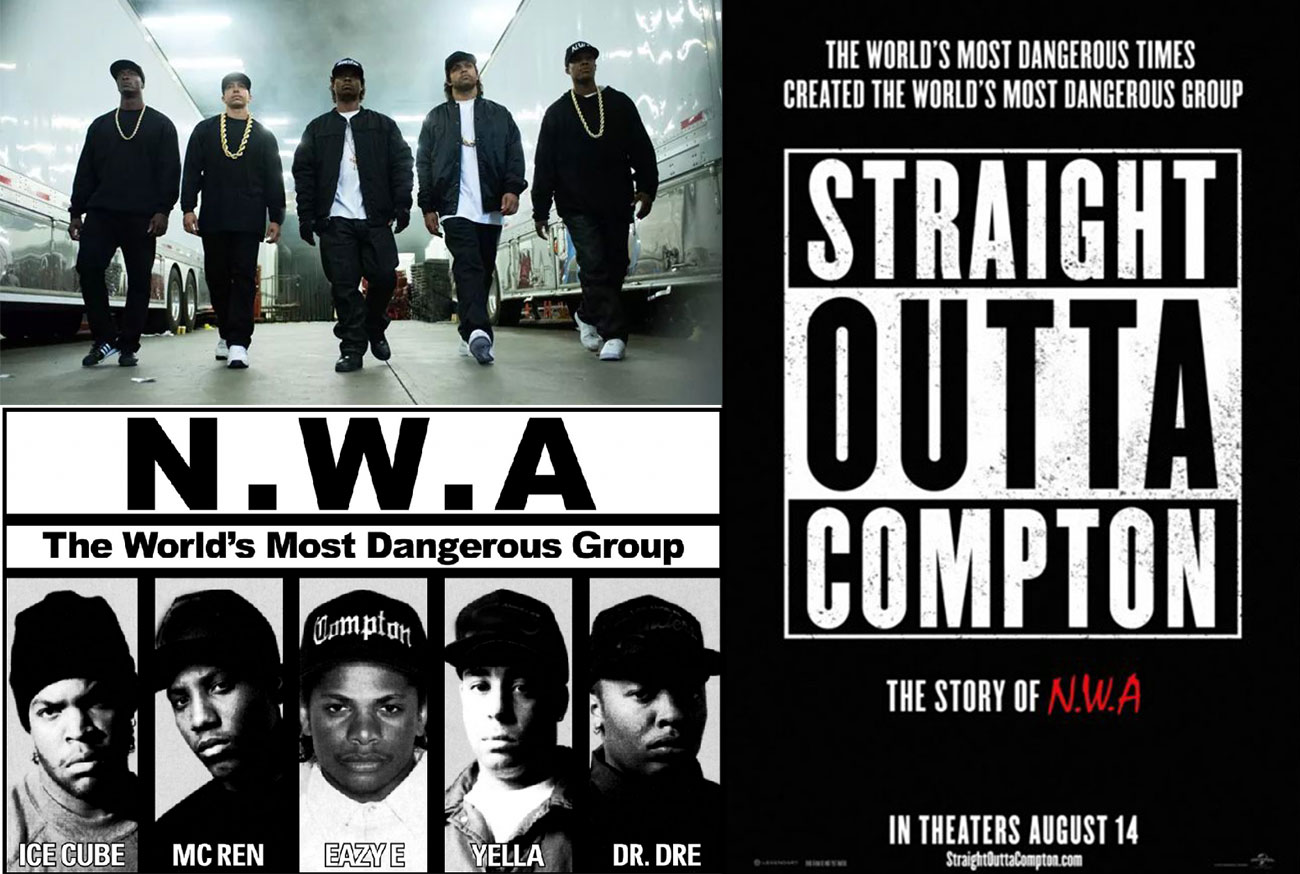

Kechiche’s attempts to conceptualize of others’ struggles by finding commonality is by no means uncommon or uncelebrated in contemporary film. Jim Sheridan found common ground with 50 Cent when making Get Rich or Die Tryin’ by taking him to where he was born in Dublin and exploring their differing experiences of 1980s New York City. In an oddly similar way, Steve McQueen launched his feature film career by exploring the Northern Irish experience of otherness in his account of Bobby Sands’ imprisonment in Hunger.

In regard to the female gaze, Blue is the Warmest Color isn’t an exemplar, but a cautionary tale in how conflating the gendered gaze with the gender of the director can obscure and severely harm incredibly brave and vital filmmaking. Especially in the case of a film that strives to achieve a sense of understanding between distinct groups that suffer similar forms of oppression.

Emma Houxbois is a fiercely queer trans woman whose natural habitat is the Pacific Northwest. She is currently the Comics Editor for The Rainbow Hub and co-host of Fantheon, a weekly comics podcast.