The Female Gaze: Dido and Noni, Two of a Kind by Rachel Wortherley

Directors Amma Asante and Gina Prince-Bythewood illustrate that when a story is told through the eyes of the second sex, themes, such as romance, self-worth, and identity are fully fleshed out. By examining an 18th century British aristocrat and a 21st century pop superstar, it proves that in the span of three centuries, women still face adversity in establishing a firm identity, apart from the façade, amongst the white noise of societal expectations.

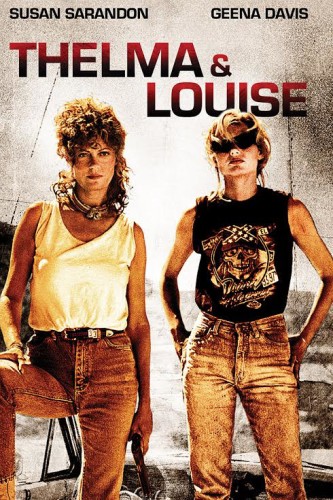

Thelma and Louise: Redefining the Female Gaze by Paulette Reynolds

The violence may decrease as the movie progresses, but Thelma, Louise – and we – become comfortable about their actions as the film winds down, because they were now tapped into our veins, nourishing our battered spirits with acts that said, “See? We recognize your anger, cause we’re angry – and we’re not going to take it anymore.”

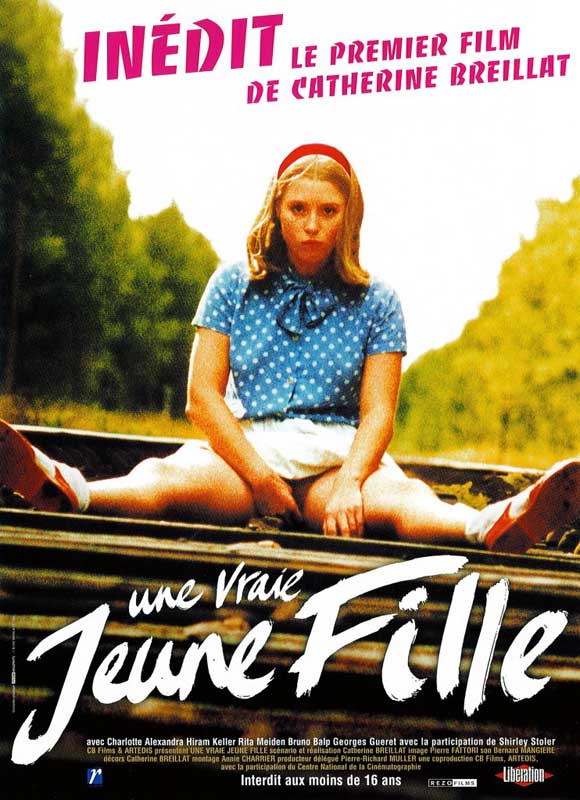

How Catherine Breillat Uses Her Own Painful Story to Discuss the Female Gaze in Abuse of Weakness by Becky Kukla

The female gaze is more than simply “reversing” the male gaze; it allows for a questioning of why the male gaze is so inherently built into cinema and why women are aggressively sexualised within cinema. With Abuse of Weakness, Breillat attacks both of these concerns whilst also actively encouraging identification with Maud – our female protagonist.

The Capaldi Conundrum: How We Attack the Female Gaze by Alyssa Franke

In any fandom based on visual media, fangirls are attacked because of the way the female gaze is misunderstood and misrepresented.

Murder Spouses and Field Kabuki: The Female Gaze in NBC’s Hannibal by Lisa Anderson

The show treats the bodies of living women with the same respect that it treats those of dead ones.

The Male Gaze, LOL: How Comedies Are Changing the Way We Look by Donna K.

The body is no longer a Lacanian reflected ideal, it is a biological mess that often exists beyond anyone’s control. The effect of this convention is two-fold–a bait and switch of expectations but also the creation of a sense of biological sameness: man or woman, everybody poops. By placing the body in a biological space instead of a symbolic one, physical comedy is questioning the visual tendencies of subconscious desire.

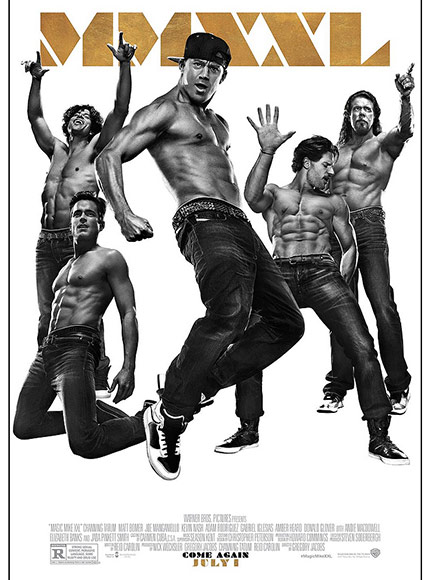

Please Look Now: The Female Gaze in Magic Mike XXL by Sarah Smyth

The trailer offers a kind of meta-advertisement, recognising the very marketing strategies that attracted people, including women, to the previous film. Cutting between clips of the men performing various routines, the trailer includes the line, “We didn’t want to show the best parts of the movie in this trailer but it was very very hard to resist,” before inviting the audience to #comeagain this summer.

No, You Can’t Watch: The Queer Female Gaze on Screen by Rowan Ellis

The desire to show a complex version of yourself seen with male characters in the Male Gaze, alongside a desire for a complex version of your partner seen with male recipients of desire in the Female Gaze, combines in the Queer Female Gaze to produce sexual and romantic relationships often rooted in friendship.

“Everything Is Going To Be OK!” – How the Female Gaze Was Celebrated and Censored in Cardcaptor Sakura by Hannah Collins

In other words, there was a concerted effort to twist the female gaze into a male one under the belief that CLAMP’s blend of hyper-femininity and action would be unappealing for the male audience it was being aimed at.

Catherine Breillat’s Transfigurative Female Gaze by Leigh Kolb

Breillat’s complete oeuvre (which certainly demands our attention beyond these three films) delivers continually shocking treatment of female sexuality presented though the female gaze. She wants us to be uncomfortable and to be constantly questioning both representations of female desire and our responses to those representations, and how all of it is shaped by a religious, patriarchal culture.

Jo March’s Gender Identity as Seen Through Different Gazes by Jackson Adler

The male gaze either holds Jo back from the start, or else shows an “educational” transformation from an “unruly” female into a “desirable” young woman who knows her place.

Pleading for the Female Gaze Through Its Absence in Blue is the Warmest Color by Emma Houxbois

The female gaze, such as it exists in a world that denies its existence, is an insular one that exists between Adele and Emma as opposed to how the film itself is shot. The film presents the case for the female gaze by examining what happens when it’s withheld.

Women in a Man’s World: Mad Men and the Female Gaze by Caroline Madden

In fact, many of the clients grow to appreciate the benefit of the female gaze, making their products truly (for the most part) appealing to women. This makes more profit than the false patriarchal ideas of a woman’s wants and needs. With the character of Peggy, Weiner is able to let us see the advertising world from the female gaze to criticize the falsehood that lies in selling female products with a male gaze.

Just Not Into It: Why This Female Gazer Opts Out by Stephanie Schroeder

I choose to only support women-centered film and TV efforts as a funder, promoter and, indeed, gazer, if the intent, casting, storyline, and other elements are female-positive. There’s really just too much misogynistic and women-negating/woman-hating media in the world for me to do otherwise.

A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night and Scares Us by Ren Jender

Amirpour’s camera (the magnificent cinematography is by Lyle Vincent) lingers over Arash’s beauty–his high cheekbones and large, long-lashed eyes under a dark, curly version of James Dean’s pompadour–in a way few male filmmakers would.

When the Girl Looks: The Girl’s Gaze in Teen TV by Athena Bellas

In this moment, then, Elena is completely relieved of the conventional position of girl-as-object, and is therefore able to occupy a different position as a desiring subject. By purposefully making herself invisible, Elena momentarily evades and perhaps refuses to be defined by the adult male gaze that governs girlhood.

The Female Gaze in The Guest: What a View! by Deirdre Crimmins

Pinning down what makes the camera use a female gaze can be a little tricky, as we have all lived within the male gaze for so long. It is commonplace to see women on display disproportionately while male characters go fully clothed. The gaze’s assumption of heterosexuality also carries over to the infrequently used female gaze, making it slightly more visible. It is this consumption of the male body in The Guest which initially establishes the film’s gaze as female.

Shishihokodan: The Destructive Female Gaze of YA Supernatural Action Romantic Comedy by Brigit McCone

Recognizing the function of Ice Prince/Wolf in YA SARCom implies the continual defeat of the Whore as structural necessity in male writings also – as a pursuing character she must be resisted to generate sexual tension, regardless of whether the male author is Team Madonna or Team Whore. The destructive impact on the self-image of female viewers is pure collateral damage, just as our SARCom is poisonously emasculating for male viewers.