“Are you ready to be worshipped? Are you ready to be exalted?”

Oh boy, are we!

Magic Mike XXL, this summer’s sequel to the surprise hit of 2012, Magic Mike, is a celebration of (heterosexual) female sexual desire. Centred on male stripping, Magic Mike XXL thoroughly recognises and foregrounds the pleasure of women within the film and within the audience; women are (finally) recognised as having sexual desire, and of gleefully and ravenously pursuing. In this piece, I will discuss how this celebration of heterosexual female desire creates a new space for the female gaze within cinema. Although exciting and radical, I will also flesh out why this conceptualisation is also difficult and slippery. However, ultimately, I suggest that truly productive message of Magic Mike XXL is in the way in which it creates a masculine image, a male spectacle, to be looked at, affording (heterosexual) women the privilege – and the permission – to look.

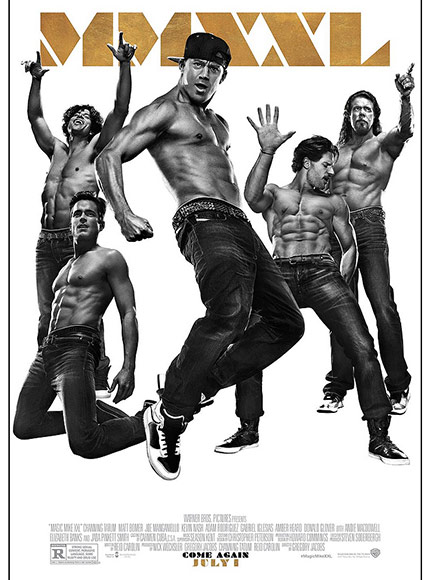

Magic Mike followed young and unemployed Adam (Alex Pettyfer) who enters the seedy world of male stripping after being introduced by Mike (Channing Tatum). Although the film contained many blatant strip scenes to be used for the audience’s entertainment, it also attempted to be something other than a gratuitous stripping movie. Directed by Academy Award-winning Steven Soderberg, the film was a Serious Picture, all washed-out colours, mumbled dialogue, and loose camera work. The sequel, however, offers a much more conventional (and sexually entertaining) story. We are reunited with Mike who, after leaving stripping to work full-time on his furniture business, is dissatisfied with his new lifestyle. He decides to rejoin his fellow strippers including Matt Bomer’s Ken and Joe Manganiello’s rather subtly named, Big Dick Richie for one last hurrah. After some quick and unimportant narrative exposition to explain the loss of Pettyfer and Matthew McConaughey (in the first film, he played club owner, Dallas), the boys hit the road to perform one last time at a stripping convention (yes, this is apparently a thing).

More explicitly than its predecessor, Magic Mike XXL is aware of the sexual pleasures to be had from male stripping. The trailer offers a kind of meta-advertisement, recognising the very marketing strategies that attracted people, including women, to the previous film. Cutting between clips of the men performing various routines, the trailer includes the line, “We didn’t want to show the best parts of the movie in this trailer but it was very very hard to resist,” before inviting the audience to #comeagain this summer. The previous film may not have been an explicit piece of erotic entertainment, but, for this film, the marketers are clear that Magic Mike XXL is to be enjoyed, to be devoured and, most radically, to be looked at.

In Laura Mulvey’s famous account of the male gaze, she posits that, in traditional Hollywood cinema, men are the active bearers of the look whereas women are the passive objects of the look. She argues,

“In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female… In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness.”

Positioning the audience’s look with that of the (traditionally male) protagonist, the internal and external male gaze constructs the sexualized and objectified image of woman. In this way, the female gaze is dismissed; female sexual desire and the act of female looking do not exist.

In traditional Hollywood cinema, the man is the possessor of the look whereas the woman is the object of the look

Considering the ways in which the female gaze is privileged in the film, Magic Mike XXL productively breaks down oppressive phallocentric structures within cinema. The men perform strip teases and erotic dances several times throughout the film both for the pleasure of the women in the film and for the women in the audience. Their final show is constructed under a flurry of excitement and anticipation, making the final release of their performance all the more satisfying. Most radically, women are actually depicted as in charge of their sexual desires and pleasures. The film introduces a new character, Rome, played brilliantly by Jada Pinkett-Smith. Rome owns a strip club where the majority if not all of the audience are Black women (side note: Has there been a mainstream film in recent years that so explicitly portrayed sexual desire within women who are not white? That alone is worth celebrating). Mike asks Rome to accompany them to the convention as their MC, and Rome commands the entirety of the performance. She calls the women in the audience queens and goddesses; she asks the audience what they want; she is effectively a Black woman in charge of white men. For the sexual pleasures it affords women, and for the autonomy it gives women over these pleasures, Magic Mike XXL offers a radical construction of the female gaze.

However, as much as we can praise Magic Mike XXL for this construction, the conceptualization of the female gaze problematically works within a heteronormative framework. Queer men and women as well as non-binary genders complicate this construction. Are women the only group of people afforded the space to look Magic Mike XXL? Interestingly, the trailer does not exclusively aim its erotic spectacle at women, creating instead a gender-neutral invitation to look at these men. However, the clips in the trailer and, indeed, scenes in the film, locate this primarily within the realm of heterosexual female desire. The people who attend the shows are women, the people who the men talk about entertaining are women, and the people who are invited to look are women. This is not to say that Magic Mike XXL isn’t aware of a possible homoerotic or even homosexual appeal. In one scene, the men attend a drag show where they also participate in a voguing competition. Developed out of queer African American communities in Harlem, the men’s voguing situates them within the framework of queer male spectacles. Also, as part of the film’s promotional campaign, the cast of Magic Mike XXL attended the 2015 LGBT pride parade in Los Angeles. The cynical may say they did so simply for the free publicity. But their willingness to embrace their sexualised roles in queer communities recognises a step forward in traditional ideas of masculinity, and a more fluid construction of the gaze.

But let’s be clear. The film primarily operates in a heteronormative framework whereby heterosexual women desire the men. Perhaps we should turn our attention not to who is afforded the look, but how the look is set up in the first place. In cinema, men are not to be looked at. To do so risks being feminised or homoeroticised; both run the risk of emasculation that traditional conceptualizations of masculinity cannot handle. Yet, here, the men offer up their bodies as spectacle, as something to be looked at. Of course, the men don’t embody the level of objectification conventionally embodied by women. For one, their bodies – all pecs, arms and abs – display the traits of the traditionally successful masculine body. As Richard Dyer claims in his essay, “Don’t Look Now,” “Muscularity is the sign of power-natural, achieved, phallic.” It is this, then, that even as we look, reminds us that these men are not passive objects, but hard, active, and, most crucially, masculine. For another, this passivity also refuses to extend to the narrative. As Mulvey claims, when objectified in cinema, woman “tends to work against the development of a story line, to freeze the flow of action in moments of erotic contemplation.” As the active protagonists on-screen and with key roles off-screen (the story is based on Tatum’s own life, and he has production roles in both movies), the men refuse to be simply passive objects of erotic contemplation.

But Magic Mike XXL is more subversive than it seems. Even as these seemingly traditional images of masculinity are renewed within the film, they are undercut by the free way in which the men offer their bodies as spectacle, as something to be looked at. As Tatum says in an interview, “We’re definitely trying to make [our stripping movie] a little different and a little bit less misogynistic. I’m not trying to get very meta about it all because at the end of the day, it’s just for fun.” And, ultimately, isn’t this what feminism is about? Sex is not sinful. When there’s mutual consent, enjoying it visually, aesthetically, and physically, is not sinful. Magic Mike XXL finally offers heterosexual women, if not anyone else, the space to enjoy this kind of sex and, if, as Tatum says, you can have fun while you’re at it, well, then that truly is a pleasure.

o.k. this is an honest question. Should this movie, or all movies, look to satisfy all different ways of attraction? and as a follow up is that possible?