Written by Brigit McCone as part of our theme week on Sex Positivity.

In Lisa Cholodenko’s The Kids Are All Right, a lesbian couple justify their preferred choice of pornography – gay male porn – by the fact that erections make desire excitingly visible and unarguable. The essence of sex positivity is shared arousal, yet, as Nora Ephron and Meg Ryan famously reminded audiences of When Harry Met Sally, female arousal and orgasm are easy to visually fake. Male craving for confirmation of orgasm in their own porn-watching leads to the “cum shot” becoming a standard trope of male-oriented pornography. But how can female arousal be visually expressed? If women stereotypically prefer to read literary erotica over watching porn, with erotica’s descriptions of the interior sensations of female arousal, is that because many women imagine that female performers of porn are uncomfortably simulating their pleasure? Can there be a clitoral cinema of female arousal, and what would it look like?

I would like to investigate that question using examples from three female-authored films: The Piano, Turn Me On, Dammit!, and Secretary. Judged only by their premises, they appear to be the height of exploitation – The Piano explores the sexual blackmail of a mute woman, Turn Me On, Dammit explores the lustful fantasies of a slender, blonde Scandinavian teenager, and Secretary explores an inexperienced young woman’s desire to be spanked and dominated. Yet, by making the female erotic imagination and self-stimulation central to their aesthetic, each of these films became erotic classics for female audiences. How?

The Piano

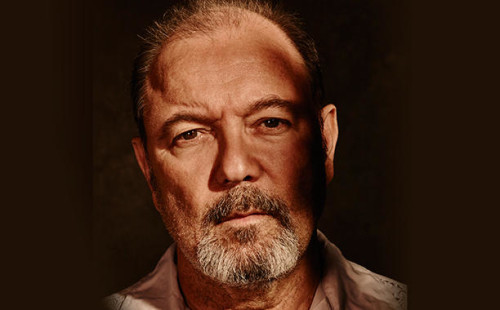

Written and directed by Jane Campion, The Piano contains some equal opportunity nudity and straightforward sex scenes, but it also disrupts the male gaze and centers the female spectator at key moments. Consider the scene in which Harvey Keitel’s Baines is examining Holly Hunter’s Ada from every angle, with casual male entitlement, as she plays her piano. Lying on the floor, he discovers a small hole in her thick, woollen stocking. The hole is symbolically clitoral to the female audience, as Baines circles his finger slowly over the little patch of heightened sensation and Ada gasps, but for the male audience it offers no spectacle. It is, rather, an evocation of the sensation of clitoral stimulation, in the same way that a woman licking an ice-cream may evoke oral sex to a male sexual imagination.

With Ada reaching through a crevice of wood to play secretive piano notes, Campion portrays the instrument as inherently sensual. Later comes a lovingly lit shot of a naked Baines caressing and rubbing the piano itself with a cloth. The hetero-female audience can take pleasure in both the spectacle of his body, and the suggestive quality of his attentive and caressing touch, but the female body is removed from the realm of spectacle. Instead, Baines is caressing the piano as a symbol of Ada’s voice and will, representing his deeper appreciation for her. Some critics (including Bitch Flicks) have said that it is problematic for Ada to fall in love with a man who is sexually blackmailing her. I would suggest, however, that, in a society that normalizes the purchase and conquest of women, it is Baines’ initial desire to negotiate, and his eventual total rejection of models of ownership,to request that Ada shows active desire for him, that marks him as her chosen mate.

Sam Neill’s controlling husband Stewart voyeuristically peers through a chink in Baines’ cabin to see his sexual play with Ada. At the moment at which Baines performs oral sex on Ada, Stewart’s gaze is distracted by his dog licking his hand. If Stewart carries the male gaze and male identification in this scene, then Jane Campion playfully interrupts that gaze to turn the man’s own hand into a symbolically clitoral site, vividly evoking the sensation of being licked for female audiences. The Piano, and its reputation as peculiarly erotic to women, is perhaps the strongest evidence that the female imagination responds to clitoral symbolism on a level that equals male susceptibility to phallic symbolism.

When Neill’s Stewart submits to Ada’s exploring his naked body with her hands, the male body becomes available to woman as spectacle and tactile pleasure while the woman herself remains clothed. If the male audience is uncomfortable with this passivity, they can identify with Stewart’s own discomfort, which explodes when Ada reaches the taboo territory of his backside, and he pulls up his hose and dashes from her, eyes averted. Just as his relationship with the Maori is colonial and acquisitive, Stewart’s only model for sex is male conquest and female submission. Just as Baines has surrendered to Maori language and culture, so his model for male/female relationships is a negotiated dual surrender and an attempt to learn the meaning of Ada’s piano language. The film’s finale rewards Baines’ model of negotiated interdependence and dual surrender over the Stewart’s domineering conquest model, with clitoral cinema triumphant.

Turn Me On, Dammit!

Depictions of female masturbation as erotic spectacle tend to focus on a woman moaning softly as she caresses her face, breast and thighs, running her fingers through her hair. The clitoris, effectively, becomes dispersed and distributed across any secondary sexual characteristics that the male audience happens to find attractive, hence the weirdly clitoral scalp of compulsive hair caressing. Female writer-director Jannicke Systad Jacobsen of Turn Me On, Dammit!, by contrast, opens with her teenaged heroine lying clothed on the floor, her hand jammed down her panties, frantically rubbing her clitoris, breathing rapidly and screwing up her face in unphotogenic arousal. This realistic depiction of masturbation immediately establishes the woman as sexual agent, not object. Because it is solitary and largely unphotogenic, masturbation has no function but to be the expression and release of female arousal.

Alma is masturbating to a phone sex hotline, where a male voice describes a hot encounter in the imaginary realm, like narrated literary erotica. Despite its sexed-up publicity, Turn Me On, Dammit! features only one brief, confusing sex act, as Alma is poked in the thigh by the naked erection of her crush, before he immediately withdraws. Instead, the film is saturated with Alma’s erotic imagination as she narrates imaginary encounters over fragmented photographs, ridiculous surrealism and vivid close-ups. Fragmenting the encounters in this way evokes the partial and inadequate imagination of a sexually inexperienced girl, attempting to project what sex might be like. Her fantasies include older men to whom she is not attracted, as well as female rivals, capturing the wide ranging of a horny teenager’s exploratory imagination. By combining fragmented visuals with Alma’s own narrated voiceover, the female viewer never feels an intrusive male gaze. The teenaged female voice of desire and sexual curiosity dominates and narrates throughout.

Secretary

Although the film is directed by Steven Shainberg, he is sensitive to the female origins of his story, adapted by Erin Cressida Wilson from a short story by Mary Gaitskill. Determined to portray the sexual awakening of a submissive woman, rather than the focussing on the pleasure of a dominant man, Secretary harnesses many of the same techniques used by the fully female-authored The Piano and Turn Me On, Dammit. Where Baines demonstrated his attentive, caressing nurture by lovingly wiping Ada’s piano, James Spader’s Mr. Grey demonstrates attentive, caressing nurture to the delicate, vulva-reminiscent orchids in his office. The flowers symbolize burgeoning arousal and desire explicitly in the heroine’s own fantasy sequence, as giant blooms burst open behind Mr. Grey. This fantasy sequence is alternated with shots of the heroine’s frantic, realistic masturbation. Like Turn Me On, Dammit!‘s Alma, Secretary‘s Lee is fully clothed during her masturbations, emphasizing that they are expressions of arousal rather than spectacle. After the film’s most potentially degrading act of domination, where Lee is required to bare her ass while Mr. Grey masturbates over it, the act is reclaimed for audiences as having been arousing for Lee, by her immediate withdrawal into the bathroom to masturbate over the memory of it. A middle-aged woman in a neighbouring stall is shown overhearing her masturbation with a look of compassionate understanding that emphasizes the universal female experience of arousal and desire. Finally, however, it is Lee’s own narrating voice, like Alma’s, that owns the film and challengingly asserts her active role in submitting.

So, can we say that these three films – The Piano, Turn Me On, Dammit! and Secretary – are sex-positive films? I would argue that their clitoral aesthetic of female-authored desire and imaginative sensation make them sex-positive for their female audience. However, in the world of the film, its men are still technically committing acts of sexual harassment where the woman consents by her imagination rather than her voice. This harassment is reclaimed for the female audience by our insight into the heroine’s desire. Can we assume that the male heroes are aware of the women’s desire, because they’ve read it on her face or in her subtler physical responses? We are still a long way from a society that takes it for granted that women should voice their desires, and that sex should be openly negotiated. But recognizing and developing a clitoral aesthetic of film is a step in the right direction. A cinematic language of female desire can be harnessed to support conversations about female needs and sensitivities.

Brigit McCone became obsessed with Harvey Keitel after seeing The Piano at an impressionable age. She writes short films and radio dramas. Her hobbies include doodling and reveling in trashy romances.