At the beginning of The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution, the new documentary from Black filmmaker Stanley Nelson, the first interviewee, Ericka Huggins, brings up the hackneyed tale of the blind men and the elephant to describe participation in The Black Panther Party (the largest political organization that made up the Black Power movement of the ’60s): those at different levels and in different cities had different understandings of the organization and widely different experiences. After I saw the film at The Independent Film Festival of Boston, I couldn’t help thinking that the metaphor was a pre-emptory excuse for what many would find lacking in the film. At the very end postscripts for each person who made up part of the Panther leadership appeared–but none of the women are mentioned, an inexcusable omission since the film itself has plenty of interviews with women who were Black Panthers (though all of them could use more screen time). Some of the film’s most incisive moments came from Kathleen Cleaver, a well-known decision-maker and spokesperson for the group in the ’60s, and Elaine Brown, who explains that the era’s radicalism reached down to the most unlikely places: “I was a cocktail waitress in a white strip club two years before I joined The Black Panther Party…The rage was in the streets. It was everywhere.” Brown went on to head the organization for a few years in the ’70s; she, alongside cofounder Bobby Seale, was one of the first people who ran for public office on its platform (she has since denounced the film). The film touches on the sexism in the organization (the way ’60s “radicals” treated women in their ranks–in every group–was a big part of the original impetus for the women’s movement), but cannot seem to make the connection to the treatment of the women we see interviewed in the present day.

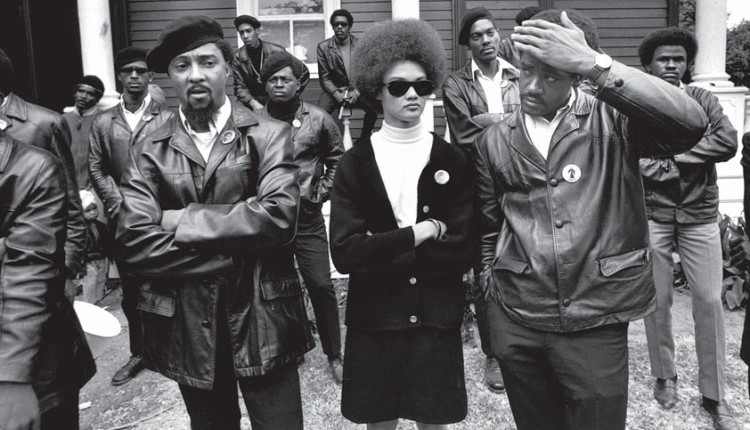

What a shame because the film is packed with history hardly anyone teaches, presented in a lively way with music from the era that isn’t the usual overplayed ’60s hits (including some catchy propaganda songs produced by the Panthers themselves) along with tons of great vintage footage of the Panthers at times juxtaposed with present-day color interviews with the people we’ve just seen in ’60s black and white (in the Panther uniform of a beret, leather jacket–and a rifle). The film quickly sets the context of the violence of the ’60s against Black people (including assassination of civil rights leaders) with founders Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale organizing a sort of armed guard for their local community (at first specifically to prevent police violence toward Black people–for which we still haven’t implemented a solution) in Oakland, California. We jump into this action without much back story: we don’t see or hear much of the Party’s Ten Point Program (all of which is relevant today: decent housing, education and health care, full employment and a living wage, prison abolition plus an end to police brutality), but we do see Panthers with guns in the state capitol building in Sacramento.

The archival clips are a double-edged sword. White news organizations and talk shows of the time presented The Panthers either as a threat or as “radical chic,” so the film, though compiled in the present day by a Black male director, can’t help taking on some of the same, non-nuanced tone, even as it features many different present-day narrators explaining the action for us. Co-founder Huey P. Newton comes off mostly as paranoid, frustrated and violent. He was all of those things, but he was also a brilliant strategist (one interviewee calls him, “a visionary”) who saw that Black people who were engaged in “survival” mode (including those who made their living with criminal activity) could be recruited to put their energy collectively into radical activism: this epiphany was a big part of why the Panthers caught on so quickly in cities all across the United States–and its framework spread beyond its borders: inspiring, among other groups, the Irish Republican Army. After the heyday of the Panthers, Newton wrote his Ph.D. thesis (he graduated high school functionally illiterate but later taught himself to read) on the forces (most egged on by the FBI) that broke up The Black Panther Party, but the film seems intent on making him just a cardboard, drug-addled villain, mad with power.

The film even sells notorious misogynist and purveyor of violence against women, Eldridge Cleaver, short. Although those interviewed point out that Cleaver’s literary pedigree (the book he had written in prison, Soul on Ice, had received fawning reviews in the New York Times and other prestigious publications: its misogyny was not unusual for widely praised books of the time, even “radical” ones) helped direct white people’s attention to the party, the film doesn’t bother to excerpt this still highly quotable book even though the ideas it laid out were at least partly responsible for attracting a child of the Black privileged class, like Kathleen Cleaver (formerly Kathleen Neal), away from her position in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to The Party and to Cleaver himself. Instead we hear from a former leader of The Young Lords (a Puerto Rican Nationalist group) say, “Eldridge had this incredible ability to encapsulate a thought that stabbed right into the heart of the enemy. Now, was he insane? Fuck, yeah.” We hear of his irresponsibility in getting other Panther members killed, but we get no clue of why people would want to follow him in the first place.

In fact the film, for the most part, neglects the emotional engagement members needed to have with the ideals and community around them to make the sacrifices they did (most members were continually harassed by police who also harassed their families). We see heart-warming footage of Panthers serving free breakfast to children (which is where the Federal government got the idea) and hear from one of those now adult children on what the program meant to her, but we hear (again briefly) from Ericka Huggins about joining the Panthers with her husband John without noting that he was assassinated by a rival Black Power faction (these tensions, were, as always, exacerbated by the FBI) when he was just 23.

We do see emotionally affecting footage of Fred Hampton the Chicago Black Panther leader who was building alliances with poor whites and Latino groups before he was assassinated by the FBI (his bodyguard was an informant: the FBI is still “gathering information” on “terrorist” suspects in this highly error-laden method). He tells a crowd, “We can’t fight racism with racism. We fight racism with solidarity.” The mother of his now adult son (she was in the late stages of pregnancy when Hampton was killed) tells of being in the same bed when he was shot (he was 21: an echo of the young Black people killed by police in the US more recently).

We even hear from some of the police officers who helped take down the party. Like the police who brutalized civil rights protestors interviewed in Eyes on the Prize they have no regrets and have faced no consequences for their actions. And like many police officers today they have a remarkable lack of self-reflection: one describes seeing “the cutest, little Black girl” and is completely flummoxed when after he says hello, she retorts, “Fuck you, pig,” though he knew very well what the police had been doing to the community. We see footage of “stop and frisk” used on Panthers (and other Black people who aren’t in the party). Some of today’s militarization of the police started as a reaction to The Panthers: the first SWAT teams were set up in California to respond to the “threat” The Black Panther Party posed. The head of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover encapsulates the philosophy we see in action when he states, “”Justice is incidental to law and order.”

The film is well worth seeing, but in some respects reminded me of a presidential campaign commercial: I’ve never felt so compelled to read up on the incidents and people depicted in a documentary to feel better informed. Although Bobby Seale is still alive, he was not interviewed for the film (but it has plenty of vintage footage of him in interviews and otherwise) and Angela Davis (also still alive) who was one of the most famous defendants in a Panther trial (she was acquitted of supplying guns to Panthers who committed serious crimes with them) is completely absent even in archival footage. And for the record, Kathleen Cleaver is now a law professor at Emory University and is active in anti-racism work. Elaine Brown was the campaign manager who helped elect Oakland’s first Black mayor and now works for radical prison reform.

[youtube_sc url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BeAsxK7PRa0″ iv_load_policy=”3″]

___________________________________________________

Ren Jender is a queer writer-performer/producer putting a film together. Her writing. besides appearing every week on Bitch Flicks, has also been published in The Toast, RH Reality Check, xoJane and the Feminist Wire. You can follow her on Twitter @renjender