The radical notion that women like good movies

|

| The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) |

|

| Shock |

|

| Sally |

Jessica Critcher loves to write about feminism and gender issues, and she is a regular contributor to Gender Focus. While she loves living in Boston, she often misses Honolulu, where she earned her bachelor’s degree in English (and forgot that there was such a thing as snow).

The films of Studio Ghibli provide their viewers with a rich variety of female characters from warrior princesses to love-struck adolescents, curious toddlers to powerful witches. These characters owe a great deal to the prototypes of European fairy tales and Japanese folklore and in many ways are traditional versions and depictions of femininities, but there’s an underlying sense of joy for feminist viewers in that these girls and women are active, subjective and thoroughly engaging. I’m focusing here on young girls in the lighter end of Ghibli’s production including sisters Mei and Satsuke in My Neighbour Totoro, Kiki in Kiki’s Delivery Service and Chihiro in Spirited Away.

|

||||

| Spirited Away |

Ghibli films tend to blend fantasy and reality so that magic and flight are acceptable parts of the worlds the characters inhabit. Girls especially tend to possess magic powers or particular appreciation of them and this is shown in an unexceptional manner. While Kiki raises some eyebrows in her new town, it’s because the townsfolk don’t see many witches, not because they don’t believe in their existence. Similarly, although Kiki is an outsider, there is a distinct lack of threat to her for being so. In Ghibli worlds girls are fully entitled to fly on broomsticks, as long as they don’t congest traffic, and 13 year olds are allowed to pursue their cultural practices of living alone. In My Neighbour Totoro when Mei tells Satsuke and their father about her encounter with Totoro, after initial disbelief they embrace the truth that there are friendly nature spirits in the area, even leading to father taking the girls to pay their respects to the forest’s deities.

This acceptance of magic is refreshing and marks a clear difference to American cartoons where ironic references are embedded in children’s fantasy to appeal to parents. In this way parents are encouraged to indulge, but secretly laugh at their children’s engagement with fantasy. There’s no knowing irony in Ghibli films, instead they are focussed on telling children’s stories for children and the lack of distinct boundaries between the magic and the mundane are part of this child-centred view. That the protagonists are predominantly female makes for a collection of films focussed on girls’ adventures and triumphs where girls’ experiences are trusted and valued.

Children, like women, are often depicted as having a close connection to the supernatural; that they can see things the rest of us cannot. Indeed Mei and Satsuke seem privileged more than anything to be invited to join the Totoros’ night-time nature ritual. Dancing and flying with creatures the rest of the world (the Ghibli world at least) would revere but aren’t lucky enough to encounter. Chihiro doesn’t have a natural affinity for magic but she’s gifted in the solving of magical problems like how to clean a dirty river spirit.

Mei, Satsuke, Kiki and Chihiro all work within the magical world as part of their quest narratives. Mei and Satsuke are dealing with the illness and potential death of their mother and a move to a new home. Kiki has moved away from her parents according to witch culture and Chihiro seeks the return of her parents from the spiritual realm where she’s been trapped and they’ve been turned into pigs.

|

| My Neighbor Totoro |

The absence of parents is a common way to allow independence to young females from fairy tales to Jane Austen and unlike for orphaned boys in fiction it can also represent a removal of patriarchal influence in general. It’s not just that these girls don’t have parents guiding them or checking up on them; they are also free to create their own rules of engagement with the world.

One way that all four girls find meaning and self is through work. Satsuke in school and house work, Mei despite being very young does gardening, Kiki sets up her delivery service and Chihiro works in the bath house. All of them do a lot of cleaning. There’s an interesting mix of public and private here and certainly the suggestion that domestic labour can be especially rewarding (for example Kiki’s paid work can provide anxieties and problems). But is the culturally feminine nature of this work an issue? In Chihiro’s case cleaning is linked to subservience and being a captive to the domestic but for the others (and eventually for her) it’s a tool of empowerment and liberation. Does such labour inevitably have negative associations of female drudgery?

Another way that selfhood and identity is achieved by these girls is by flight. Most obviously for Kiki where her broomstick is literally the means of earning a living and saving a friend’s life but also in how Totoro and Cat Bus fly Mei and Satsuke away from their worries and later to their mother. Chihiro’s flight is more anxious, as her encounters with magic are generally, but still serves to move her closer to self discovery by being the time she gives Haku his name so leading her to the rediscovery of her own.

|

| Kiki’s Delivery Service |

Not everybody believes that Ghibli heroines represent empowered femininities. I’ve been rather selective in the choice of films to cover but even if I’d widened the selection I stand by my view. Ponyo for example wasn’t included as its heroine isn’t really a girl but although it’s a variation on the disempowering The Little Mermaid the core message is rather different. Ponyo accepts a loss of powers because they were never entirely hers and the sea’s power remains with the feminine; Ponyo’s sea-goddess mother.

There’s been significant note of the glimpses of knickers we get in Ghibli films like when Kiki is flying and generally when there’s any rough and tumble. There’s merit in the argument that this could be voyeuristic representations of young girls but it can also be seen as further expressing their freedom and activity. These girls don’t worry about skirts riding up because they totally lack vanity and are preoccupied with altogether more important missions. We’re not given alluring peeps at nubile bodies but girls in action which female bodies so rarely are; that gaze is usually reserved for male bodies. If female passivity is alluring then the kinetic energy of these girls places them beyond that.

What’s pleasurable about these films from a feminist perspective is their alliance with joyful, engaged and active girlhoods. These girls don’t wait for princes and don’t focus on their appearances but determinedly pursue their missions, however difficult.

____

Rosalind Kemp is a film studies graduate living in Brighton, UK. She’s particularly interested in female coming of age stories, film noir and European films where people talk a lot but not much happens.

|

| The Princess and the Frog (2009) |

|

| Tiana and Prince Naveen-turned-frog |

|

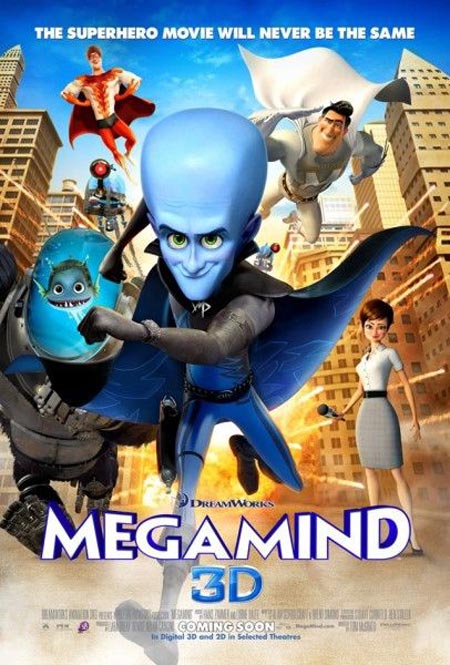

| Megamind (2010) |

|

| Roxanne Ritchi, voiced by Tina Fey |

|

| Hal and Roxanne |

|

| Shrek (2001) |

|

| Artwork by William Steig |

|

| Fiona, imagined by Dreamworks |

|

| Nala to Simba: “Pinned you again.” |

I should say first, let’s throw the whole “But this is how lions act” argument out the window. Lions are not actually “kings” of all animals; they do not actually get along with prey when they’re feeling like singing a song, or learn to eat bugs from them; when (male) lions become subadults, they have to leave their pride, and no, they can never come back. Etc., etc., etc.

|

| One big, happy family? |

When it comes to Nala, her role has always frustrated me a lot. Ignoring that it might not work with the plot already in place, it was quite disappointing that Nala did not take over partially or fully in Simba’s absence. She is always shown, especially early on in the film, to be Simba’s equal, and she is perhaps even more intelligent, or at least a more naturally sound leader throughout the film, while Simba tends to be comparatively a bit more immature and in need of multiple characters propelling him into responsible/rightful action. This isn’t a critique of Simba’s likeability or abilities, but merely to say that in all aspects, Nala would have made at least a decent fill-in.

|

| Simba and the more cunning Nala |

She comes up with better ideas then he does. She is the one who starts Simba thinking about his past and his future. Yet, despite the fact that she left the pride lands to find help, she also does not challenge Scar’s right to rule. She does little more than Sarabi to work toward getting a better life for herself and the other lionesses, only leaving the pride lands to seek help (read: a different male lion). Only when Simba returns to the lionesses stand up to Scar. This is because a new male has been found to lead them. The lionesses are very much kept in the shadow of the male lions.

I think this is really one of the main and most problematic aspects of the film: it basically boils down to the fact that an entire group of strong female characters are unable to confront a single male oppressor; to do so, they need to be led by a dominant male. It almost sucks more that Nala is such a strong, independent, intelligent, savvy female character and still ends up constrained by this plot device. It doesn’t say a lot of positive things about the role of women or about the importance of female characters in this film.

|

| Scar: Simba’s evil gay uncle? |

The characters are animals, but their voices show racist stereotypes. Even though The Lion King takes place in Africa, two white American actors are used for the voice of Simba, the hero. However, the hyenas who are bad characters in the film, speak non-standard English and are played by actors like Whoopi Goldberg and Cheech Marin. The villain, Scar, suggests homosexuality.

Many critics saw a racial subtext to the villainous outsiders, noting that the racialized voices of the hyenas hewed to hackneyed stereotypes of African American and Hispanic threats to nice kids from the suburbs who stray too far from home.

|

| Racialized hyenas? |

There is plenty to enjoy about How to Train your Dragon. The animation is lovely, the story is energetic, and the landscape feels fresh and inviting. The film also contains a number of plot elements that are far too common in children’s films these days.

|

| How to Train Your Dragon (2010) |

The film doesn’t make much use of its female characters. Hiccup’s mother is dead like many mothers in animated films geared towards children. Her only purpose is to provide the male protagonist with some sort of emotional complexity. There is a female elder who picks which student slays a ceremonial dragon but she is only in the film for a few seconds and she has no dialogue. The most prominent female character is a young Viking hotshot named Astrid. She is the star pupil in dragon training who is tough as nails and always on edge. If this character seems familiar it’s because she is. She’s Colette from Ratatouille, Eve from Wall-E, and Tigress from Kung Fu Panda. She is the latest in a long string of female characters that are tough and talented but second in importance to the males. Perhaps the most iconic example of this trend for our current generation would be Hermione from Harry Potter. She’s the brains but not the hero.

|

|

|

|

There are a number of other problems with female sidekicks of the types that I have just listed. One is that they are only skilled when it comes to playing by the rules. Characters like Astrid and Tigress are shown as being obsessed with following instructions. They work hard to receive approval from their teachers both of whom are male. Likewise Colette told Linguini that it was their job to “follow the recipe.” Female characters like this are shown operating specifically within the boundaries that have been laid out for them by male superiors. They are not shown to have the insight to break rules and challenge the system the way the male protagonists do. Another problem with these types of female sidekicks is that while they are very talented they often don’t possess the talents that the stories they exist in value. Take Hermione for example. While she is incredibly smart, the story she exists in only treats intelligence as second in importance to bravery, which is what Harry embodies. With How to Train Your Dragon, it’s the same problem. Astrid is strong-willed, physically powerful, and full of fighting spirit, but this is not what is valued in a story that ultimately preaches gentleness and a sense of compassion, which is what Hiccup represents.

The film’s final setback is that it boasts antiwar and antiracism credentials that it doesn’t live up to. While it is true that Hiccup is presented as the symbol of peace between humans and dragons, the story also uses a battle as its climax. Hiccup and Toothless have to save everyone by defeating a giant dragon in combat in a sequence that is clearly set up for audience suspense and enjoyment. Even more troubling is the relationship between the humans and the dragons at the end of the film. While they may be at peace the dragons have become Viking pets. It is a peace that is built on a hierarchy and it makes the film’s message very disturbing if the dragons are to be viewed as a metaphor for another race of people. This movie wants to have it both ways. On the one hand it uses the dragons to tell a story about different races rising above war. On the other hand it portrays the dragons as less intelligent pets because the audience will find this amusing and empowering. The title of this movie is not How to Coexist with a Dragon.

How to Train Your Dragon is an attractive and at times enjoyable movie, but in the end its problems outweigh its charms. The characters are too simplistic, the plots are too familiar, and the politics are too compromised. If a film is going to teach politics to children (or adults for that matter), the film should challenge them, not cater to them.

|

| Disney’s Mulan (1998) |

If you watch the actual movie, as I did, as a European expat teaching in a Hong Kong international school and grappling with cross-cultural questions on a daily basis (you try teaching A Bridge To Terabithia to a class of city-dwelling Chinese boys) — not so much. Mulan has always been a problematic text for me because it tries so hard to be culturally sensitive and gender-aware that it positively creaks, and those creaks can be heard by the least-savvy member of the target audience. Its sins are not the sins of historical omission of, say, Snow White or Sleeping Beauty, but are all the more egregious because they come from a place of awareness. Mulan is an attempt to fix something that was perceived to be, if not wrong, unbalanced. This clumsy attempt to wedge The Ballad of Mulan into the rigid, alien form of a Disney narrative (which, among other things, demands musical numbers, a comic sidekick and a Prince Charming to come home with at the end) doesn’t fix anything, and only serves to remind us what is broken about our global culture. The road to hell is, as ever, paved with good intentions, particularly when it heads from the West to the East.

Back in the mid-1990s, Disney had a very specific agenda when it came to China. They wanted to get back into the regime’s good books after the PR disaster that was Kundun. They wanted to replicate the success of 1994’s The Lion King in the region. And they wanted to soften up the government and local politicians when it came to breaking ground on Hong Kong Disneyland, and paving the way for the Shanghai park. What better way to win friends and influence people than by honoring a popular Chinese legend in the form of a Disney film?

So, ever mindful of the accusations of racial insensitivity that had been tossed at Aladdin and Pocahontas, and anxious to get it right this time, Disney sent key artists on the movie to China, for a three-week tour of Chinese history and culture. Three weeks! You can totally “do China” in three weeks. This was enough to give them all the visual reference points they needed, and the whistle-stop, touristic nature of their impressions is very much in evidence on the screen. Every Chinese guided tour cliché is tossed into the scenery hotchpotch, from limestone mountains to the Great Wall to the Forbidden City. This isn’t so bad – other Disney movies are set in a vague Mittel-Europe of mountains, forests and lakes – but the loving attention paid to trotting out the visual truisms of courtyard complexes, brush calligraphy, cherry blossoms et al is just window-dressing. Mulan does look like China, but only if you’re leafing through your holiday photos back in your Florida office.

It’s a shame the screenwriters weren’t sent on the same tour. Mulan is peppered with crass jokes about Chinese food orders (because that’s what Americans can relate to about Chinese culture, right?), disrespectful references to ancestor worship, superficial homage to Buddhist practice and some kung-fu styling, of the Carradine kind. Given that Wu Xia is a rich, diverse, centuries old storytelling tradition, it also seems a shame that the writers didn’t draw more deeply on those perspectives. Instead, they send Mulan on a tired, Western Hero’s Journey, plugging her variables into the 12-step formula tried and tested by countless Hollywood protagonists. She doesn’t ever think like a Chinese woman. She’s never more American than when her rebellious individualism (bombing the mountaintop) wins the day – her filial obedience was only ever lip service paid as a convenience in Act One. Even in Han Dynasty China, it seems, it’s best to follow the American Way.

There’s nothing particularly Chinese about Mulan herself, who is so brutally meant to be not-Disney Princess and not-Caucasian it hurts to look at her for long. Poor little Other. She’s shown wearing Japanese make up, and has a facial structure more suggestive of Vietnamese than Chinese (Disney really was embracing post-colonialism). For half the movie, she also has to be not-female. The lack of detail on a 2-D Disney face meant the animators had to design her as able to switch between genders via her hair – and something subtle going on with her eyebrows. The resulting face evokes, more than anything, a pre-op kathoey who hasn’t yet taken advantage of Thailand’s booming plastic surgery clinics in order to make zer gender-reassignment complete.

Oh, Mulan. She’s meant to be non-offensive, and she ends up being not-anything. Despite claims to the contrary, she’s not a feminist hero. She has to dress as a boy to achieve selfhood, and refuses political influence in order to return to the domestic constraints of her father and husband-to-be. The movie itself doesn’t even pass the Bechdel test, if you consider that the only topic the other female characters discuss is Mulan’s marriageability – a hypothetical relationship with a man. The final defeat of the antagonist is achieved by the male Mushu riding on a phallic firecracker, as Mulan flails helplessly at his feet. Positive female role model? Case closed.

Nonetheless, Mulan did brisk business worldwide – apart from in China. It perhaps had most impact on second or third-gen Asian-Americans, who could relate to the over-simplified view of China, and feel a connection with this stereotypical version of “their” culture, lacking many other reference points. For Asian-Americans across the board, not just Chinese-Americans, Mulan’s brown, angular features represented something vaguely familiar, which made a delightful change. For Chinese-Chinese, Mulan was a thoughtless Western blunder. For Asian-Americans, particularly little girls, Mulan was a rare screen representation of aspects of their selves. Mulan drove the story, at the center of almost every scene, instead of pushed to the periphery as a “typical Asian” shopkeeper, geek, or whore. They could even purchase Mulan merch – although it’s still impossible to buy a doll, a t-shirt or a pin showing Mulan in warrior mode, she’s always got her hair down, and is wearing her hanfu frock. For a generation of Twinkies, Asian on the outside, American on the inside, Mulan was significant, a role model in the Disney pantheon of princesses. It didn’t matter that she was a bit low-rent (no castle, not really a princess), and she hadn’t snagged a proposal by the end of the movie (that happily ever after is a ‘maybe’), she allowed Asian-American girls, many of them adopted, to hold their heads high. And for that alone, you have to love her.

Mulan wouldn’t seem like such a frustrating, failed attempt to push gender and cultural boundaries if it had been followed up by other stories of empowered female warrior heroes. A Disney version of Joan of Arc or Boudicca could have been a blast. Unfortunately, since 1998, it’s been pretty much princess as usual. On the bright side, Disney achieved some of their other goals with Mulan. Hong Kong Disneyland (itself the subject of accusations of crass cultural insensitivity) has been doing brisk business since 2005, thanks to a US$2.9billion investment by Hong Kong taxpayers (of which I was one). The majority of tourists are from mainland China. They come to marvel at Western icons like Mickey, and an all-American Main Street that’s a replica of the one in Anaheim. Thanks to the ubiquitous presence of Mulan images, they stick around. It feels a tiny bit more like they might have a stake in the happiest place on earth.

There’s something else, though, that I can’t not notice about the NYT article: In the entire 1,187-word article, only about 200 words (3 paragraphs) were devoted to one of the highest honors and most controversial moments of the night: Oprah Winfrey winning the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award. She’s the first Black woman to win the award (Quincy Jones won in 1995, the only Black man to win it), yet her win has been called “boneheaded” and “a shameless bid for a ratings boost,” largely because her contributions to the film industry are seen by insiders as lacking.

|

| Nick Offerman, the man who plays Ron Effing Swanson. NBC Photo: Mitchell Heath, from the Hollywood Reporter interview. |