|

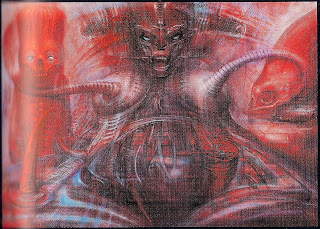

| Victory V (Satan), HR Giger, 1983 |

|

| Biomechanoid, HR Giger,1976 |

|

| Hermes, Engineer |

Prometheus simplifies what Alien proposed, it interchanges between penile and vaginal imagery: creature with knob-like head that flowers into a vagina, gigantic vagina dentata scene, penis-probe emerges, both male and female genitalia are likely villains. In the proud tradition of a design that’s been rumoured to be inspired by human body bits, skeletons and BMW car parts, it’s all perfectly justifiable.

The eco-feminist opinion of the medicalization of childbirth is that it alienates the child from the mother and vice versa, the mother has to be delivered from her baby, the child has to be saved from its mother’s stifling uterine constrictions, and now I refer quite obviously to Elizabeth’s self-inflicted caesarean. Okay, fine, she didn’t do to herself literally, she got the reluctant machine to do it for her, to get that twisting, bulging, rapidly expanding alien body out of herself. I got an intense feeling of déjà vu during that scene: seriously, get the damned thing out quickly. More painkillers please. The scene has been hailed as a pro-choice metaphor, an assertion of reproductive rights, a claim to ownership of the female body by the female herself, the machine being calibrated for the male body hindering Elizabeth’s attempt to save herself a reference to the ongoing battle for reproductive freedom in the United States, but it is also a modern feminist embrace of medical technology. I agree with the movie’s usage of the term ‘caesarean’; ‘abortion’ would imply a vaginal expulsion of the thing, after killing it within the womb, considerably more invasive and terrifying. Eco-feminism not only gets the boot in that scene with the embrace of mechanistic, but also because Elizabeth, as opposed to cloned Ripley in Alien Resurrection4, isn’t keen to claim any part of the alien growing inside herself as her own.

Prometheus is gorgeous but sports little of the multi-layered psychological profundity of its predecessor (I can barely think of Prometheus as a prequel to Alien, so let’s just say it tried to ride on its predecessor’s glory and it partly succeeded. It has its niggling flaws, like I don’t know why a biologist would approach an entirely new alien species in a ‘here kittykittykitty’ manner, or why with all that fantastic technology the geologist and biologist got lost in the first place. It’s okay, they’re expendable. Elizabeth Shaw however is important and impressive, she’s softer and smaller than the androgynous, tough warrior that is Ripley, however no less formidable as a heroine.

I’m all geared up for a sequel now and want to know how the Engineers are going to react when a female version of themselves lands up at the door with an android’s head in a duffle bag, questioning them about an experiment gone awry.

Notes:

1 Barbara Creed “The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis”, Routledge, 1993

2 Stanislav Grof “HR Giger and the Soul of the Twentieth Century”, HR Giger, Taschen 2002

3 Jane Caputi, “Goddesses and Monsters: Women, Myth, Power, and Popular Culture”

4 “I’m the monster’s mother”, Ripley, Alien Resurrection (1997)

*Edit 27/6–This is what I assumed the DNA scene from the movie was suggesting. I’m not sciencey enough to know what kind of life forms exist out there or how they come about. When and where the female human is supposed to have come into the picture I can only guess. It was a pretty scene though.

**Edit 4/7–It just occurred to me that this whole thing might be orchestrated by a Queen. Is Ridley going to spring a surprise on us??

Rhea Daniel got to see a lot of movies as a kid because her family members were obsessive movie-watchers. She frequently finds herself in a bind between her love for art and her feminist conscience. Meanwhile she is trying to be a better writer and artist and you can find her at http://rheadaniel.blogspot.com/.