|

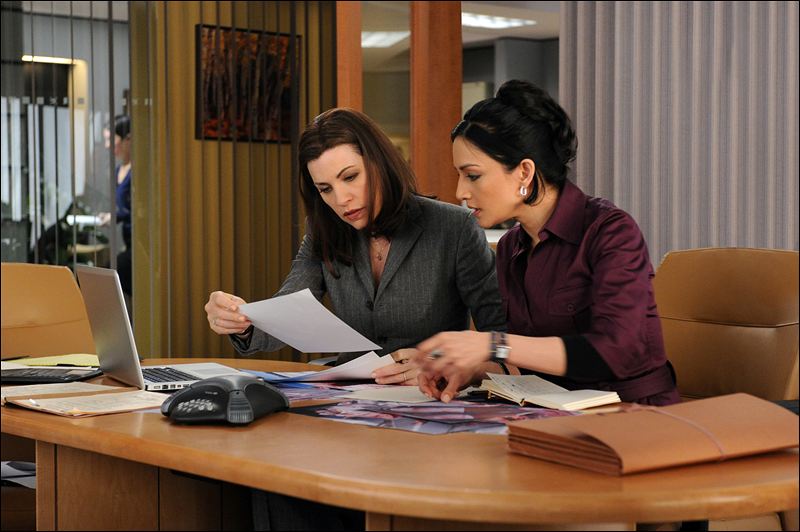

| The Good Wife |

Guest post written by Melanie Wanga.

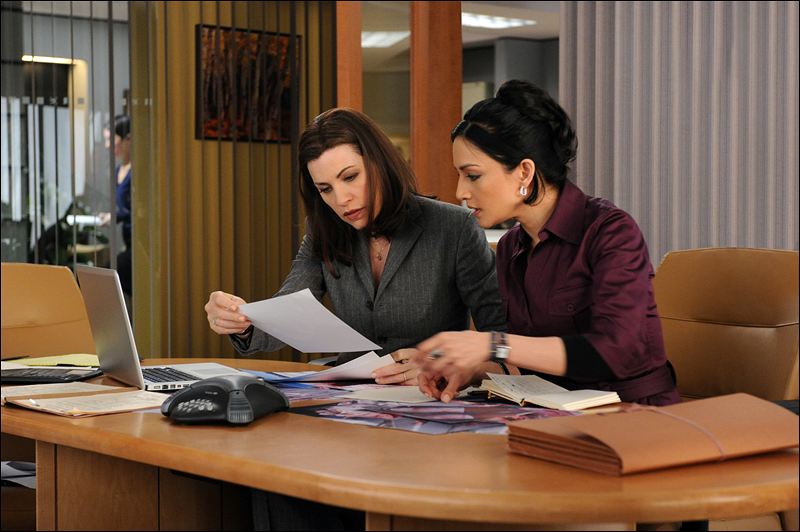

In the crowded market of American television, one would suggests that The Good Wife is one of the most feminist shows out there.

First, the main character is a woman. But not any woman: complex, strong-willed and hard-working Alicia Florrick (Julianna Margulies), whose husband Peter, state’s attorney, cheated very publicly with a prostitute. Despite its title, The Good Wife is not a soap about how love conquers all: rather, it’s the story of Alicia’s emancipation.

The qualities of TGW are plenty: it’s intelligent, complex, thoughtful but packed with explosive twists and turns. The legal stories are well written and more importantly, the casting is premium.

Actually, the acting ensemble is one of the strong suits of the show: actors like Alan Cumming (Eli Gold) or Christine Baranski (Diane Lockhart) are impressive and play wonderful their parts, when equally gifted actors regularly guest star in complex roles (Michael J. Fox, Matthew Perry…)

If we agree on the notion that “feminism is the radical notion that women are people,” then The Good Wife is definitely feminist. Women of the show are deeply human, flawed, and developed.

Which is a quite explosive fact in a legal drama, a genre usually crippled by stereotyped non-emotional lawyer-type characters.

The Good Wife doesn’t hide behind tricks or facilities: the same complexity applies to all the characters. We are even treated with character development of women and men of color, and the show doesn’t shy away from race issues.

If the women are strongly written, women of color sadly don’t escape stereotypical representations: Latinas are ‘fiery,’ and most often than not Black women are depicted as ‘angry.’

In honor of Black History month, I’d like to focus on the portrayals and specifics of the four most important women of color on the show: Kalinda Sharma (Archie Panjabi), Dana Lodge (Monica Raymund), Geneva Pine (Renee Goldsberry) and Wendy Scott-Carr (Anika Noni Rose).

————————–

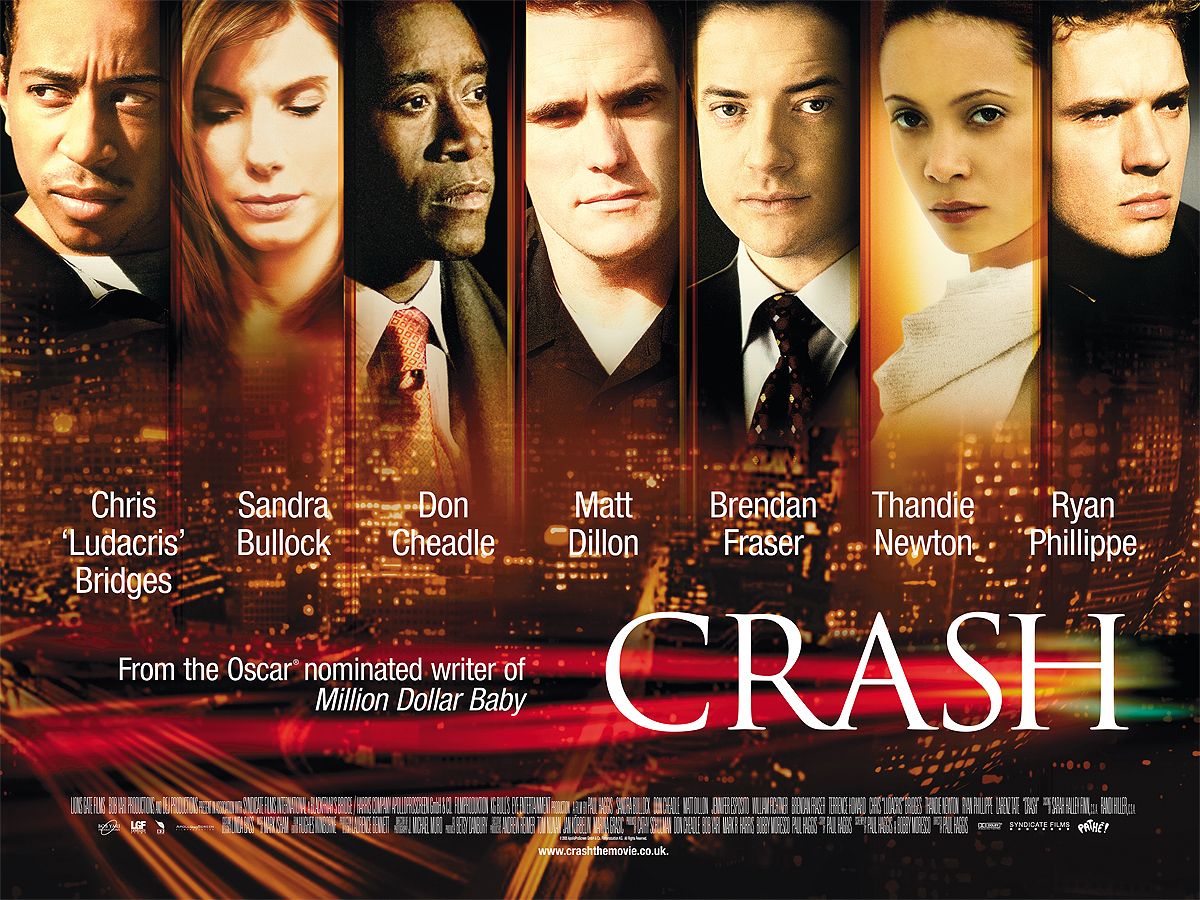

|

| Archie Panjabi as Kalinda Sharma |

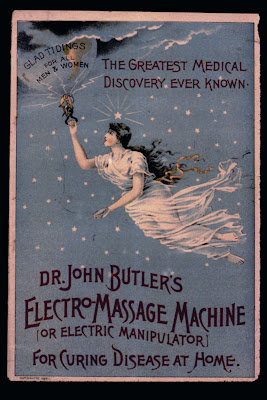

KALINDA SHARMA (Archie Panjabi)

When you think ‘women of color in The Good Wife‘, the obvious answer is Kalinda Sharma. Interpreted by actress Archie Panjabi, who received an Emmy Award for her performance, she’s one of the most important characters on the show, and a viewers’ favorite.

As an Investigator for Lockhart & Gardner, Kalinda exhudes confidence, intelligence … and sex. She often uses her physical traits and sexuality to obtain crucial information. Every character seems to succumb to her charms.

Panjabi said in an interview that the character was not very defined at first, and simply based on an “Erin Brockovich investigator” type. That’s why I would argue Kalinda wasn’t specifically written as a woman of color. No reference is made to her social and ethnic backgrounds. Even after four seasons of the show, we still don’t know much more about her ethnicity. We are left with an “ambiguously brown” character.

A huge part of Kalinda’s characterization lies in her sexuality. Extremely secretive and mysterious, she’s defined as bisexual (“I’m not gay. I’m… flexible,” she says), but she falls in the “not too bi” trope as she’s in fact slept with more men than women. She was even married to one [spoiler] (who comes back in her life in the most disastrous storyline of the series). A good portion of the characters have been seduced by the investigator: Peter, Dana Lodge, FBI agent Lana Delaney… She also has an ongoing “will they/won’t they” affair with young lawyer Cary Agos (Matt Chruzcy). And, her boss Will Gardner aside, it’s made very clear that every man on the show is attracted to her.

When Kalinda is seen in the company of other women, like Lana or Dana, the show quickly remembers us with frequent close-ups of her usual attire (namely, low-cut tops and knee-high boots) that “even the guys want her.” Kalinda’s sexuality pleases the male gaze.

One of her main psychological traits is her duality: behind her apparent calm, cold and detached aspects (‘the submissive exotic girl’), she can become violent and extreme if the situation calls for it, which is another sexual cliché. She’s not apologetic about her sexual behavior, unless it concerns Alicia (another one of her limits).

The fact is, as viewers, we know a lot about Kalinda’s sexuality. But we know oddly less about her motivations or internal dilemmas. Which sometimes gives the impression that her complexity is only apparent. That her “mystery” is factice, a ploy to serve the story. It’s clear the writers didn’t want to define Kalinda by her race or ethnicity, so they defined her by her sexuality and non-conventional work ethic.

But is writing women of color as if they weren’t minorities at all is making them more real? I’m pretty sure not.

———

|

| Monica Raymund as Dana Lodge |

DANA LODGE (Monica Raymund)

Dana is an assistant at Peter’s office. She enters the show on season 2 and starts to work alongside Cary Ago. In many aspects, she fits very well the Latina’s trope: she’s fiery and out-spoken, throws tantrums, and is guided by her emotions — particularly her jealousy.

This psychological trait is even more prominent when she interacts with Kalinda, and viewers learn the two are ex casual-sex friends.

Working with Cary (who, as it’s been said on the show, has “a thing for ethnic women”), Dana is entangled in a love triangle with him and … Kalinda.

Her sexuality is a heavily shown trait. But when Kalinda uses sex to her advantage, Dana is used at her own expense. She has a relationship with Cary, but he stills pines for Kalinda. And when Kalinda flirts with her, it’s for inside information.

Dana Lodge is blindsided by her own emotions: she can’t see that Kalinda’s using her, nor that Cary’s not really attached to her. The character shows strong feelings and speaks them loudly, but can’t see through them.

In her final scene on the show, Dana slaps Kalinda on the face, demonstrating once more her ‘fiery’ temper. At the end, Dana loses her job AND Cary.

———

|

| Renee Goldsberry as Geneva Pine |

GENEVA PINE (Renee Goldsberry)

In season 4, Peter Florrick, Chicago’s state’s attorney, runs for governor. There’s plenty of discussion on how he leads his office. Rumors of racial bias are floating around and are used by his political enemies. In one telling scene, Florrick asks his black assistant Geneva Pine if she thinks he has such bias. When she answers yes, a typical response is offered to her: rather than trying to understand her position, Florrick declares she’s wrong and misunderstood his intentions. But then, she shuts up and judgmentally looks at him. Interestingly enough, he finally listens to her main argument on why he is racially biased: he systematically promotes white males first.

This is an accurate depiction of most racial conversations in real life: I can’t count the times I’ve heard white people, when confronted with examples of racist or problematic behavior, respond: “But no, let me explain, it’s not racist. I’M not racist.” Resenting the idea of racism itself is more important than listening to the minority’s experience of it.

However, Geneva is by no means a positive character. She’s talented and driven, but she’s ‘that’ minority character written as resentful over other people victories and accomplishments.

When Cary worked at the state’s attorney’s office, she never took him seriously, even when she was teaming up with him.

Geneva acts as an obstacle to other people ambitions, but she can’t stop them. While she’s not sexualized as a Black woman, she’s showed as perpetually angry, bitter and judgmental.

The fact that Geneva often plays the ‘race card’ and is conscious of her status of woman of color is not welcomed positively on the show. Geneva is misguided, she accuses everyone of being biased. As such, she’s the stereotype of the ‘angry minority’ and ‘angry black woman’ who nobody listens to, because she’s ‘crazy, hateful and not neutral.’

Not a good look, huh?

———

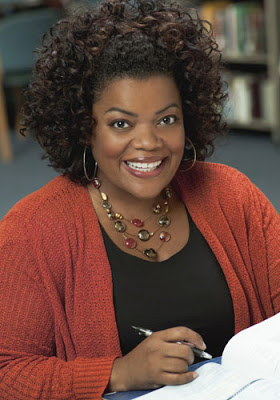

|

| Anika Noni Rose as Wendy Scott-Carr |

WENDY SCOTT-CARR (Anika Noni Rose)

The fourth notable woman of color of the show is an interesting one as she holds much more power than the others.

Wendy Scott Carr is introduced during the second season, when Peter decides to run for a new mandate state’s attorney. She positions herself as his political opponent. The fact that she’s a woman of color is precisely what gives her an edge: Peter’s sex scandal is still out there, and Wendy appears as a voice of the women. She’s everything he’s not: she’s Black and has strong family values. Even the viewers are rooting for her. She should crush Peter on the finish line.

But then, the show develops the character. Wendy reveals herself to be ‘a bitch in sheep’s clothing:’ she’s cold, calculating and deeply hypocritical. Behind her nice facade, she’s smug, has unapologetic ambitions, and despises the Florricks. And she won’t hesitate to get dirty to win the election.

When she loses the campaign to Peter, she takes her failure very personally. She then becomes a full-fledged resident villain of the show: on numerous occasions, she’ll be back to legally torment our protagonists.

Wendy is not affable, that’s a fact. What’s bugging me is the show depicts Wendy’s coldness as more reprehensible than Peter’s amorality, and as a valid reason for her to lose.

Developing a seemingly good character into a complex and ‘not so nice’ one is something The Good Wife does very well. In Wendy Scott-Carr’s case, the evolution seemed forced, and to make her come back for Will’s blood on season 3 was downright caricature. She’s not nuanced anymore: she hates Alicia, the Florricks, the Lockhart-Gardner law firm and all of their allies. She will go after our heroes for no other reason than … well, she REALLY hates them.

As much as it’s rare (and nice) to see an ambitious Black woman with actual power on TV, the traits that seem to prevail are always anger, grudge, man-hating. As if they somehow should make people pay.

———

Women of color in The Good Wife seem to follow a strange pattern. The good side: they’re all ambitious and talented. The bad side: they’re either sexualized, thus deemed attractive and complex, or they become jealous, angry and over-the-top villains.

Representing complex women of color in millennial television shouldn’t be a challenge. But, by all accounts it still is. While I applaud The Good Wife for depicting ambitious and complex characters, I can’t hide my disappointment over stereotypical traits in their women of color.

Seriously, I love my TV shows and all. But, really writers, I can assure you we, and by we I mean humanity, don’t need MORE representations of fiery Latinas and angry Black women.

———

Melanie Wanga is a French journalist based in Paris. She’s a pop culture lover, passionate reader and a feminist. Like everybody on the Internet, she also loves cats. You can follow her on Twitter: @MelanieWanga.