I’ve always loved movies. When I was a kid, nothing brought me greater pleasure than walking across those sticky floors to find the perfect seat, the scent of stale popcorn hanging in the air. My dad, my big brother, and I would always share a box of Sour Patch Kids. I loved spending those two hours inside the theater on thrilling adventures, falling in love, traveling to exotic locales, suffering terrible tragedies.

But Asian Americans didn’t seem to go on these adventures; they didn’t seem to fall in love; they didn’t travel to exotic locales. If anything, they were merely set decoration when the real protagonists of the stories got to those places. People of Asian descent didn’t seem to exist on screen at all, and when they did appear, bucktoothed and bumbling, their fleeting presence filled me with a burning shame, as if watching a family member humiliate himself in front of someone I was trying to impress.

When you hardly ever see anyone who looks like you on screen, and when the only people who look like you don’t seem like people at all, you begin to have a very limited notion of your own possibilities. This nagging insecurity I’ve lived with my whole life (and truthfully, what will always be a part of me and what drives my work) was nagging particularly loudly a few weeks ago.

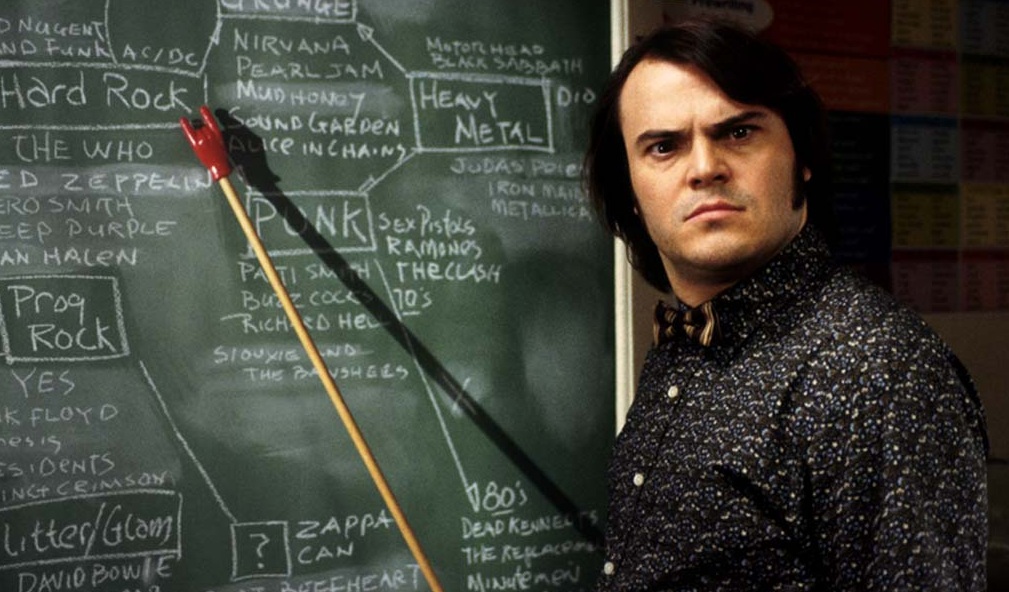

|

| Still from Screaming in Asian |

I was at CAAMfest, an Asian American film festival in San Francisco. For the last two years, I’ve been trying to raise the money to make my first feature film, The Real Mikado, a comedy about an out-of-work Asian American actress who moves back in with her parents and directs a production of Gilbert & Sullivan’s opera The Mikado to try and save the community theater. I was at the festival to sceen the first ten minutes of the film as a short and to pitch the feature for the chance at a grant.

The day before the pitch, all of the filmmakers did a practice run-through of the event, and I was the last to present. I saw these passionate, talented people pitch their films about victims of war and impoverished children, and when it was my turn, I couldn’t find my words. All I could think was, “Why should anyone care about me or my stupid movie?” After years of struggling, I was so exhausted from pretending to be far more confident than I really was and so frustrated and hurt by the constant rejection that it all finally got to me.

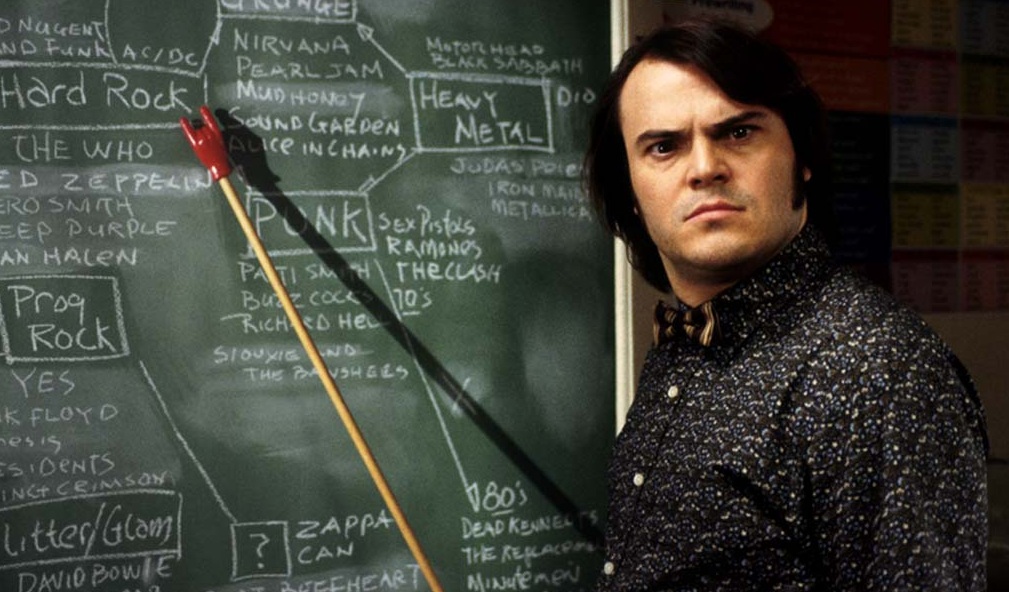

|

| Still from Screaming in Asian |

I did the one thing that a woman who wants to be taken seriously is never supposed to do. I cried. I couldn’t even hold it together long enough to wait until I was in the privacy of a bathroom stall. I did it in front of everyone. Fortunately, the other filmmakers were incredibly supportive. Some of them cried too. That night, I stayed up all night revising and rehearsing my pitch. I stood in front of a mirror staring into my own bloodshot eyes and tried to convince myself that my movie was worth making.

The next morning, on about two hours of sleep, I walked up to the podium and told a panel of judges and an audience of about 70 people about The Real Mikado. I summoned everything I had from the deepest places of my soul and gave those people everything I could about who I am and why my film needs to be made. I killed it. I did as well as I possibly could have.

Even though I gave it my all, I didn’t win the grant (that went to a wonderful documentary), but when I finished, a throng of young women from the Center for Asian American Media student delegate program came up to me and told me how excited they were about my film. They asked to take pictures with me and for advice on how to be an actor and whether or not I would watch their videos on YouTube and give feedback. One of them exclaimed, “Everything you said is what I feel!”

I had been feeling so defeated and so trivial that I failed to remember how powerful movies can be in shaping a person’s imagination and sense of self. These young women are yearning for the same thing I did and do: they want to see themselves as protagonists in their own stories; they want to go into a theater and see themselves.

Maybe this is too simple or wide-sweeping a generalization about white male privilege, but I doubt that Wes Anderson or Noah Baumbach ever wondered if their stories deserved to be told. The fact that I was filled with so much self-doubt speaks to a vicious cycle we’re all in, and we need to work together to stop it. How can we expect young girls (especially those of color) to grow up with enough confidence to be filmmakers when everything they watch is telling them that they are not valuable and that their stories don’t matter?

My film, like a lot of first features, is a personal one. It’s a little embarrassing to admit that I’m acting in and directing a movie that I wrote based on my own life. It feels more than a little self-involved to put myself on screen for all the world to see. But I realized a long time ago that if I don’t do it, no one else will.

Joyce Wu grew up outside of Detroit. Her short films have screened at festivals around the world. She was awarded a full-tuition scholarship to attend New York University’s prestigious graduate film program, where she completed her course work and is in pre-production on her first feature film, The Real Mikado. To find out more about the film, please visit: http://www.seedandspark.com/studio/real-mikado.