Outstanding Comedy Series

30 Rock (NBC): “Goodbye Forever, 30 Rock“ by Max Thornton

The Big Bang Theory (CBS): “The Evolution of The Big Bang Theory“ by Rachel Redfern

Girls (HBO): “Girls and Sex and the City Both Handle Abortion With Humor” by Megan Kearns

Louie (FX): “Listening and the Art of Good Storytelling in Louis C.K.’s Louie“ by Leigh Kolb

Modern Family (ABC): “‘Pregnancy Brain’ in Sitcoms” by Lady T

Veep (HBO): “Political Humor and Humanity in HBO’s Veep“ by Rachel Redfern

Outstanding Lead Actor in a Comedy Series

Jason Bateman, Arrested Development: “Arrested Development‘s Mancession: Economic and Gender Meltdowns in Season 4″ by Leigh Kolb

Jim Parsons, The Big Bang Theory: “Big Bang Bust” by Melissa McEwan

Matt LeBlanc, Episodes

Don Cheadle, House of Lies

Louis C.K., Louie

Alec Baldwin, 30 Rock: “The Casual Feminism of 30 Rock“ by Peggy Cooke

Outstanding Lead Actress in a Comedy Series

Laura Dern, Enlightened

Lena Dunham, Girls: “Let’s All Take a Deep Breath and Calm the Fuck Down About Lena Dunham” by Stephanie Rogers

Edie Falco, Nurse Jackie: “Nurse Jackie as Feminist Id?” by Natalie Wilson

Amy Poehler, Parks and Recreation: “Why We Need Leslie Knope and What Her Election on Parks and Rec Means for Women and Girls” by Megan Kearns

Tina Fey, 30 Rock: “Liz Lemon: The Every Woman of Prime Time” by Lisa Mathews

Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Veep

Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Comedy Series

Adam Driver, Girls

Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Modern Family

Ed O’Neill, Modern Family

Ty Burrell, Modern Family

Bill Hader, Saturday Night Live

Tony Hale, Veep

Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Comedy Series

Mayim Bialik, The Big Bang Theory

Jane Lynch, Glee: “Glee!” by Cali Loria

Sofia Vergara, Modern Family

Julie Bowen, Modern Family

Merritt Wever, Nurse Jackie

Jane Krakowski, 30 Rock: “Jane Krakowski and the Dedicated Ignorance of Jenna Maroney” by Kyle Sanders

Anna Chlumsky, Veep

Outstanding Drama Series

Breaking Bad (AMC): “‘Yo Bitch’: The Complicated Feminism of Breaking Bad“ by Leigh Kolb

Downton Abbey (PBS): “A Gilded Cage: A Feminist Critique of the Downton Abbey Christmas Special” by Amanda Civitello

Game of Thrones (HBO): “Gratuitous Nudity and Complex Female Characters in Game of Thrones“ by Lady T

Homeland (Showtime): “Homeland‘s Carrie Mathison: A Pulsing Beat of Jazz and ‘Crazy Genius” by Leigh Kolb

House of Cards (Netflix): “The Complex, Unlikable Women of House of Cards: Daddy Issues, Menopause and Female Power” by Leigh Kolb

Mad Men (AMC): “Mad Men: Gender, Race, and the Death Knell of White Patriarchy” by Leigh Kolb

Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series

Bryan Cranston, Breaking Bad: “Seeking the Alpha in Breaking Bad and Sons of Anarchy“ by Rachel Redfern

Hugh Bonneville, Downton Abbey

Damian Lewis, Homeland

Kevin Spacey, House of Cards

Jon Hamm, Mad Men: “Hey, Brian McGreevy: Vampire Pam Beats Don Draper Any Day” by Tami Winfrey Harris

Jeff Daniels, The Newsroom: “The Newsroom: Misogyny 2.0″ by Leigh Kolb

Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series

Vera Farmiga, Bates Motel

Michelle Dockery, Downton Abbey

Claire Danes, Homeland: “Homeland‘s Carrie Mathison” by Cali Loria

Robin Wright, House of Cards: “Claire Underwood: The Queen Bee on House of Cards“ by

Amanda Rodriguez

Elisabeth Moss, Mad Men: “Mad Men and the Role of Nostalgia” by Amber Leab

Connie Britton, Nashville: “Quote of the Day: Screenwriter/Director Callie Khouri Weighs In on How TV Is Friendlier to Women” by Leigh Kolb

Kerry Washington, Scandal: “Mammy, Sapphire, or Jezebel, Olivia Pope Is Not: A Review of Scandal“ by Atima Omara-Alwala

Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Drama Series

Bobby Cannavale, Boardwalk Empire: “Boardwalk Empire: Margaret Thompson, Margaret Sanger, and the Cultural Commentary of Historical Fiction” by Leigh Kolb

Jonathan Banks, Breaking Bad

Aaron Paul, Breaking Bad

Jim Carter, Downton Abbey

Peter Dinklage, Game of Thrones: “The Occasional Purposeful Nudity on Game of Thrones“ by Lady T

Mandy Patinkin, Homeland

Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Drama Series

Anna Gunn, Breaking Bad

Maggie Smith, Downton Abbey

Emilia Clarke, Game of Thrones: “The Mother of Dragons is Taking Down the Patriarchy” by Megan Kearns

Christine Baranski, The Good Wife: “So, Is There Racial Bias on The Good Wife?” by Melanie Wanga

Morena Baccarin, Homeland

Christina Hendricks, Mad Men: “Is Mad Men the Most Feminist Show on TV?” by Megan Kearns

Outstanding Miniseries or Movie

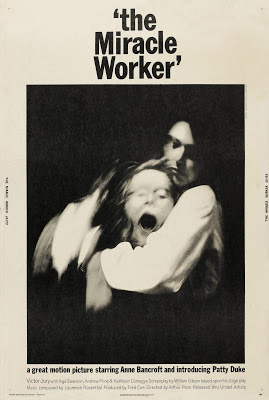

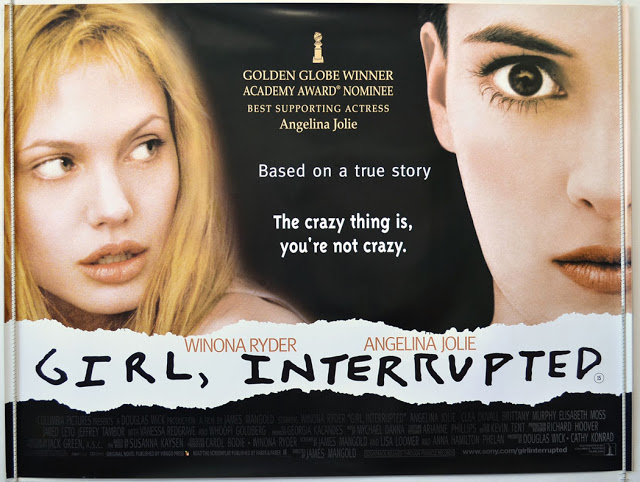

American Horror Story: Asylum (FX): “‘That Crazy Bitch’: Women and Mental Illness Tropes in Horror” by Megan Kearns

Behind the Candelabra (HBO)

The Bible (History)

Phil Spector (HBO)

Political Animals (USA)

Top of the Lake (Sundance Channel): “Not Peggy Olson: Rape Culture in Top of the Lake“ by Lauren C. Byrd

Outstanding Lead Actor in a Miniseries or a Movie

Michael Douglas, Behind the Candelabra

Matt Damon, Behind the Candelabra

Toby Jones, The Girl: “Too Many Hitchcocks” by Robin Hitchcock

Benedict Cumberbatch, Parade’s End

Al Pacino, Phil Spector

Outstanding Lead Actress in a Miniseries or a Movie

Jessica Lange, American Horror Story: Asylum

Laura Linney, The Big C: Hereafter

Helen Mirren, Phil Spector

Sigourney Weaver, Political Animals

Elisabeth Moss, Top of the Lake

Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Miniseries or a Movie

James Cromwell, American Horror Story: Asylum

Zachary Quinto, American Horror Story: Asylum

Scott Bakula, Behind the Candelabra

John Benjamin Hickey, The Big C: Hereafter

Peter Mullan, Top of the Lake

Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Miniseries or a Movie

Sarah Paulson, American Horror Story: Asylum

Imelda Staunton, The Girl

Ellen Burstyn, Political Animals

Charlotte Rampling, Restless

Alfre Woodard, Steel Magnolias

Outstanding Variety Series

The Colbert Report (Comedy Central)

The Daily Show with Jon Stewart (Comedy Central): “YouTube Break: Too Many Dicks on The Daily Show“ by Amber Leab

Jimmy Kimmel Live (ABC)

Late Night With Jimmy Fallon (NBC)

Real Time with Bill Maher (HBO)

Saturday Night Live (NBC)

Outstanding Host for a Reality or Reality-Competition Program

Ryan Seacrest, American Idol

Betty White, Betty White’s Off Their Rockers

Tom Bergeron, Dancing with the Stars

Heidi Klum and Tim Gunn, Project Runway

Cat Deeley, So You Think You Can Dance

Anthony Bourdain, The Taste

Outstanding Reality-Competition Program

The Amazing Race (CBS)

Dancing with the Stars (ABC)

Project Runway (Lifetime)

So You Think You Can Dance (Fox)

Top Chef (Bravo)

The Voice (NBC)

Outstanding Reality Program

Antiques Roadshow (PBS)

Deadliest Catch (Discovery Channel)

Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives (Food Network)

MythBusters (Discovery Channel)

Shark Tank (ABC)

Undercover Boss (CBS)

Outstanding Animated Program

Bob’s Burgers (Fox)

Kung Fu Panda: Legends of Awesomeness (Nickelodeon)

Regular Show (Cartoon Network)

The Simpsons: “Bart Simpson’s Feminine Side” by Lady T

South Park

Outstanding Guest Actor in a Comedy Series

Bob Newhart, The Big Bang Theory

Nathan Lane, Modern Family

Bobby Cannavale, Nurse Jackie

Louis C.K., Saturday Night Live

Justin Timberlake, Saturday Night Live

Will Forte, 30 Rock

Outstanding Guest Actress in a Comedy Series

Molly Shannon, Enlightened

Dot-Marie Jones, Glee

Melissa Leo, Louie

Melissa McCarthy, Saturday Night Live

Kristen Wiig, Saturday Night Live

Elaine Stritch, 30 Rock

Outstanding Guest Actor in a Drama Series

Nathan Lane, The Good Wife

Michael J. Fox, The Good Wife

Rupert Friend, Homeland

Robert Morse, Mad Men

Harry Hamlin, Mad Men

Dan Bucatinsky, Scandal

Outstanding Guest Actress in a Drama Series

Margo Martindale, The Americans

Diana Rigg, Game of Thrones

Carrie Preston, The Good Wife

Linda Cardellini, Mad Men

Jane Fonda, The Newsroom

Joan Cusack, Shameless