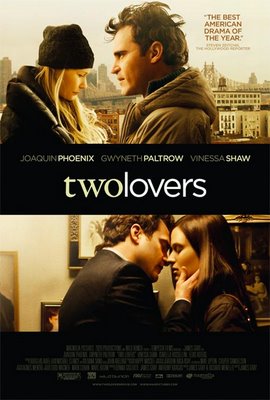

Two Lovers. Starring Joaquin Phoenix, Gwyneth Paltrow, Vinessa Shaw, Moni Moshonov, Isabella Rossellini, John Ortiz, Bob Ari, Julie Budd, and Elias Koteas. Written and directed by James Gray.

Leonard (Phoenix) is a medicated, suicidal mess of a person, who moved back in with his Jewish parents after his fiancé dumped him when it became apparent that they both carried a recessive gene that would prevent them from having children together. He helps his parents with their dry-cleaning business while also pursuing a half-hearted interest in photography. As his parents solidify a deal to sell the business, they set up their son with the daughter of their buyers. Enter Sandra (Vinessa Shaw), a pretty, sweet brunette who’s secretly liked Leonard ever since seeing him dance with his mother at the dry cleaner’s.

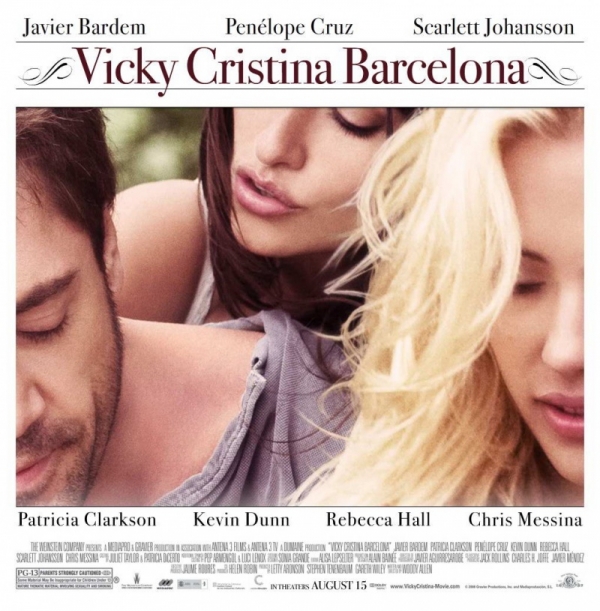

Around the time Leonard meets Sandra, he also coincidentally meets a gorgeou s, glamorous blonde, Michelle (Gwyneth Paltrow), who just moved into his apartment building. Already as a viewer, I’m wondering how I’m supposed to believe that this guy, who just attempted suicide (again) at the beginning of the film, and who keeps a picture of his former fiancé on his nightstand, falls into a situation where he’s swimming in new vagina. Regardless, he’s most taken with the hot, fun blonde (shocking) who inhales drugs on her way to club-it-up in Manhattan and who lives the rest of her life in a codependent daze. Turns out, she’s a lawyer’s assistant, and—guess what—she’s fucking the lawyer!

s, glamorous blonde, Michelle (Gwyneth Paltrow), who just moved into his apartment building. Already as a viewer, I’m wondering how I’m supposed to believe that this guy, who just attempted suicide (again) at the beginning of the film, and who keeps a picture of his former fiancé on his nightstand, falls into a situation where he’s swimming in new vagina. Regardless, he’s most taken with the hot, fun blonde (shocking) who inhales drugs on her way to club-it-up in Manhattan and who lives the rest of her life in a codependent daze. Turns out, she’s a lawyer’s assistant, and—guess what—she’s fucking the lawyer!

Much to the dismay of Leonard (and me), Michelle lives in an apartment paid for by her married lawyer boyfriend, who’s planning to leave his wife for her, and who takes her to the opera an awful lot and other whatever. Michelle sees Leonard as “just a friend” and constantly asks him to do things for her, like, oh you know, tend to her after her miscarriage and etc, just like people who’ve been friends for two weeks often do. (That scene particularly bothered me, as it paints Michelle as not just codependent but completely manipulative and codependent exclusively on men. Where are her women friends?)

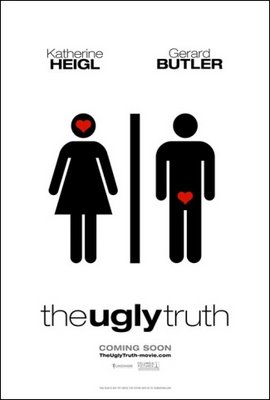

The worst part about all this is that the movie pretends these female characters have some  complexity, by at least giving Paltrow some decent dialogue to work with, but the reality is that the characters are mired in clichés. It’s hard to overlook the fact that Leonard’s two relationship choices include a sensible, sweet brunette and a wild, drug-addicted, smokin’ hot blonde, which is so completely the opposite of subversive or interesting, and actually brings to mind the Madonna/Whore dichotomy. Also, we’re meant to believe that Sandra goes along with Leonard’s wishy-washiness because she just loves him that much, and, as she blatantly says to him, she understands him and just wants to take care of him. (Gag.)

complexity, by at least giving Paltrow some decent dialogue to work with, but the reality is that the characters are mired in clichés. It’s hard to overlook the fact that Leonard’s two relationship choices include a sensible, sweet brunette and a wild, drug-addicted, smokin’ hot blonde, which is so completely the opposite of subversive or interesting, and actually brings to mind the Madonna/Whore dichotomy. Also, we’re meant to believe that Sandra goes along with Leonard’s wishy-washiness because she just loves him that much, and, as she blatantly says to him, she understands him and just wants to take care of him. (Gag.)

Michelle, on the other hand, a character based entirely on the boss-screwing-his-hot-assistant cliché, goes from dumping her married boyfriend because he won’t leave his wife, to screwing Leonard on the roof of their apartment building, all in the span of a few hours. She is a sad character, and it’s never more evident than in this moment—her need to feel desired by men, to depend on them, to be taken care of by them, always overpowers anything else she may be feeling—it’s obvious she doesn’t care for Leonard as more than a friend, and yet she makes the decision to run away with him to San Francisco. (But don’t worry; he’s taking care of the tickets and any other necessary accommodations.)

I understand this film wants to give Leonard a choice and that Sandra represents a stable life, near his family, in partnership with her family, where he’ll enjoy a financially secure future, while also pleasing his parents, especially his very concerned mother. Conversely, Michelle represents his freedom from that life, and the literal escapes he makes with her—leaving grimy, unglamorous Brighton Beach to hang out with her in the big city—further illustrate his unwillingness to remain static. That’s the part of the film I love. Phoenix does the man-child bit in a way that isn’t a cliché taken straight from an Apatow film; he somehow makes you sympathize with Leonard and his dilemma.

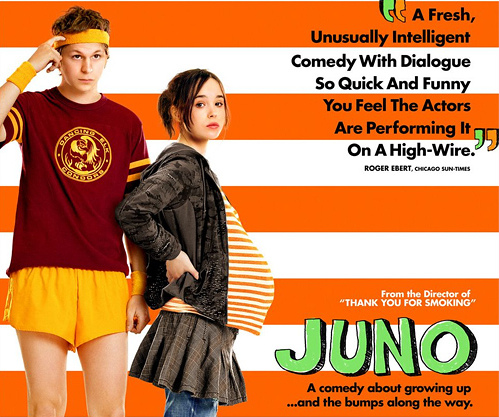

Leonard’s obvious internal conflict with embracing his Jewish heritage—th e choice Sandra represents (she’s almost a replacement mother for him)—and his desire to abandon his working-class neighborhood and subsequently the dry cleaning business—the choice Michelle represents—certainly save the film from replicating many recent comedy-dramas, where the slacker man-child lives out his slacker existence until falling in love with a gorgeous woman, way out of his league, who finally domesticates him, curing him of his adolescent slacker ways.

e choice Sandra represents (she’s almost a replacement mother for him)—and his desire to abandon his working-class neighborhood and subsequently the dry cleaning business—the choice Michelle represents—certainly save the film from replicating many recent comedy-dramas, where the slacker man-child lives out his slacker existence until falling in love with a gorgeous woman, way out of his league, who finally domesticates him, curing him of his adolescent slacker ways.

The family dynamic in particular plays out in Leonard’s choice between Sandra and Michelle. Sandra, a Jewish woman, has an obvious connection with her family. When Leonard asks her what her favorite movie is, she tells him it’s The Sound of Music, not because she thinks it’s a great movie, but because it reminds her of watching it with her family as a child. We see scenes with her and her family at her brother’s bar mitzvah, with Leonard there too, almost lurking in the background.

Michelle, however, is the opposite of Sandra, a blonde WASP, who only mentions her father once, when we hear him yelling off-screen at the beginning of the film. We never see any member of her family, and that certainly appeals to Leonard. If he chooses Michelle, he can avoid living a life his parents and Sandra’s parents seem to have already planned out for him, and Phoenix, a master at playing this type of emotionally wounded character, truly makes the audience sympathize with his struggle to get his life together.

But as much as I loved watching Joaquin work the screen, I absolutely despised the pseudo-complexity  of Paltrow’s character. (They don’t even try to make Shaw’s character into anything more than Future Doting Wife.) Michelle’s codependence isn’t interesting— no matter how effortlessly Paltrow performs it—the blonde wild-child thing is tired at this point, and the over-the-top female insecurity just completely and unapologetically lacks inventiveness. (Women can demonstrate insecurity in ways other than becoming drug addicts, passing out in bar bathrooms, screwing their married bosses, and manipulating men, I promise.)

of Paltrow’s character. (They don’t even try to make Shaw’s character into anything more than Future Doting Wife.) Michelle’s codependence isn’t interesting— no matter how effortlessly Paltrow performs it—the blonde wild-child thing is tired at this point, and the over-the-top female insecurity just completely and unapologetically lacks inventiveness. (Women can demonstrate insecurity in ways other than becoming drug addicts, passing out in bar bathrooms, screwing their married bosses, and manipulating men, I promise.)

So what the hell? Ultimately, I’m left with this question: why does a film about a man’s attempt to pull himself out of a very real darkness have to rely so heavily on traditional clichés regarding women’s experiences, while simultaneously creating an actual interesting life for the male hero?

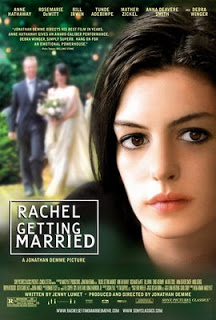

First, the poster is a poor representation of the film. While you could argue that Kym (Hathaway) is the main character, the movie is really about her and her sister, Rachel (DeWitt). The background of the movie is much more in the foreground, unlike the poster. All the characters in the film are complicated, conflicted, and ultimately complicit in the family tragedy. What Stephanie said about the anger and guilt rings true, as well as the unsentimental nature of the story. Each character behaves in cruel, selfish ways; Kym’s narcissistic, inappropriate speeches counter Rachel’s bratty outbursts of jealousy. Yet there are some weak points in an otherwise very, very good movie.

First, the poster is a poor representation of the film. While you could argue that Kym (Hathaway) is the main character, the movie is really about her and her sister, Rachel (DeWitt). The background of the movie is much more in the foreground, unlike the poster. All the characters in the film are complicated, conflicted, and ultimately complicit in the family tragedy. What Stephanie said about the anger and guilt rings true, as well as the unsentimental nature of the story. Each character behaves in cruel, selfish ways; Kym’s narcissistic, inappropriate speeches counter Rachel’s bratty outbursts of jealousy. Yet there are some weak points in an otherwise very, very good movie.