Category: Uncategorized

An Open Letter to Romantic Comedies

This is great.

via Shakesville

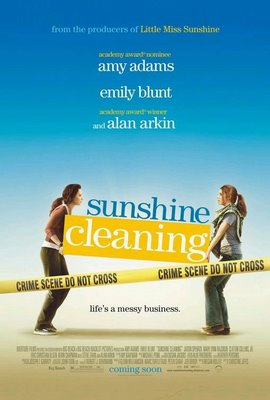

Movie Review: Sunshine Cleaning

Sunshine Cleaning: Ripley’s Pick or Ripley’s Rebuke?

This is a film I wanted to love. It’s directed by a woman (Christine Jeffs). It’s written by a woman (Megan Holley). It stars two brilliant actors (Amy Adams and Emily Blunt), not to mention one of my favorite indie-actors, who co-stars (Mary Lynn Rajskub). And for the most part, I liked it. For the most part.

Amy Adams plays Rose, a single mother with a troubled son who gets expelled from his elementary school. In order to send him to private school, she realizes her job cleaning houses won’t come close to covering the cost, so she gets the idea from Mac, the cop she’s having an affair with (her ex-boyfriend from high school, played by Steve Zahn) to start a biohazard crime-scene cleaning service. Her younger sister Norah (Emily Blunt), a darker, edgier, gothier version of Rose, goes into business with Rose after getting fired from her job as a server at a diner. Hilarity ensues. Sort of.

It’s a comedy in the sense that funny things happen, lots of bloody, yucky grossness, some witty quips from the girls’ father Joe (Alan Arkin), as well as the smile-inducing precocio usness of Rose’s son Oscar (Jason Spevack). But we quickly learn there’s some serious darkness underlying the played-for-laughs desperation: Norah and Rose’s mother committed suicide when they were young girls. That added dynamic always keeps things from veering too far into clever-indie-comedy territory but sometimes forces it a little too far into brooding-melodramatic-indie-drama territory (with a little splash of Hollywood thrown in).

usness of Rose’s son Oscar (Jason Spevack). But we quickly learn there’s some serious darkness underlying the played-for-laughs desperation: Norah and Rose’s mother committed suicide when they were young girls. That added dynamic always keeps things from veering too far into clever-indie-comedy territory but sometimes forces it a little too far into brooding-melodramatic-indie-drama territory (with a little splash of Hollywood thrown in).

So it goes like this: two sisters love and support each other in typical love-hate siblinghood-rivalry interactions, with the older sister taking on the grown-up role (however superficial it actually is—she repeats daily affirmations in her bathroom mirror for god’s sake) and the younger sister taking on the needy, irresponsible, screws-everything-up role. I enjoyed watching a movie about two insecure women with mother issues; as much as I see films and TV shows and music videos and bar brawls and daytime talk show interviews about insecure men with father issues, this was a much needed change.

The best things about this movie revolve around that sibling bond and how they managed to ma ke it through their childhoods without a mother by doing their best to take care of each other. But the whole “our mom died and ruined our lives and now we literally clean up the messes made by dead people” metaphor got slightly heavy-handed after awhile. And, as much as I hate to say it, I didn’t necessarily like that Rose’s motivation to change her life was spurred by her motherly duty to get her son a darn good education. (I’m an asshole.) About halfway through, I began to question if this movie even liked women.

ke it through their childhoods without a mother by doing their best to take care of each other. But the whole “our mom died and ruined our lives and now we literally clean up the messes made by dead people” metaphor got slightly heavy-handed after awhile. And, as much as I hate to say it, I didn’t necessarily like that Rose’s motivation to change her life was spurred by her motherly duty to get her son a darn good education. (I’m an asshole.) About halfway through, I began to question if this movie even liked women.

One scene in particular bothered me. Rose happens to run into Mac’s wife at a gas station, and even though Rose tries to avoid her, his wife confronts her anyway, making it very clear that she knows about Rose’s affair with Mac. She says something along the lines of, “I know what you’re doing.” And then, “He chose me.” It isn’t lost on the viewer that Mac’s wife is pregnant, and for a moment, as much as I had admired Rose and her determination in the beginning, I suddenly despised her.

I wanted this movie to not play into that stereotype, you know, the one about women always competing with one another for men and getting all vicious with their “keep your hands off my man” talk and never dealing with the real issue: the fact that it’s their man who’s fucking other women in the first place. (This stereotype is yet another, more subtle example of the man-child in film; by women placing blame solely on other women for their partner’s infidelity, it plays into the “boys will be boys” mode of thinking—he can’t help it, because he’s a man and therefore can’t control himself poor thing, but you, as a woman, and consequently the entire world’s moral compass, should know better.)

On the other hand, I admire the film for acknowledging how horribly women can  sometimes act toward one another. I’d almost say it’s one of the movie’s themes. The only time Rose feels the need to apologize for how her life turned out, for secretly fucking her married ex-high-school-quarterback-boyfriend, for being a single mother, for cleaning other people’s houses for a living, occurs when she fears being judged by other women, most notably when an old high school friend invites her to a baby shower, where she’ll undoubtedly see many of the women who knew her in high school as the gorgeous, envy-inducing captain of the cheerleading squad.

sometimes act toward one another. I’d almost say it’s one of the movie’s themes. The only time Rose feels the need to apologize for how her life turned out, for secretly fucking her married ex-high-school-quarterback-boyfriend, for being a single mother, for cleaning other people’s houses for a living, occurs when she fears being judged by other women, most notably when an old high school friend invites her to a baby shower, where she’ll undoubtedly see many of the women who knew her in high school as the gorgeous, envy-inducing captain of the cheerleading squad.

However, I can’t figure out if the film is deliberate in its portrayal of female interactions, and attempting to make a statement about society’s ridiculous portrayal of them (think faux-Angelina Jolie/Jen Aniston rivalry and, more recently, faux-Kara DioGuardi/Paula Abdul rivalry), or if it’s merely validating the dominant ideology that there isn’t much female sisterhood or solidarity outside of actual sibling relationships. As a feminist, I know that not to be the case, but as a feminist critiquing this film, I ultimately left the theater feeling disappointed.

I expected more from a film about women’s experiences, especially when that film is written and directed by women. I know from reading other reviews of Sunshine Cleaning that many feminist women adored the movie, if only for the fact that it’s women-centered, which is something we certainly don’t see enough of in mainstream (and even indie) cinema. And we should definitely do as much as we can to support women filmmakers, given how few of them exist. But I don’t feel content leaving it at that. It was a decent movie. We can do better.

I expected more from a film about women’s experiences, especially when that film is written and directed by women. I know from reading other reviews of Sunshine Cleaning that many feminist women adored the movie, if only for the fact that it’s women-centered, which is something we certainly don’t see enough of in mainstream (and even indie) cinema. And we should definitely do as much as we can to support women filmmakers, given how few of them exist. But I don’t feel content leaving it at that. It was a decent movie. We can do better.

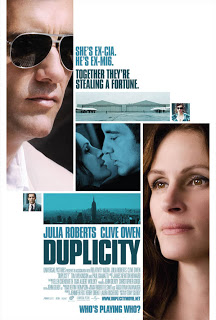

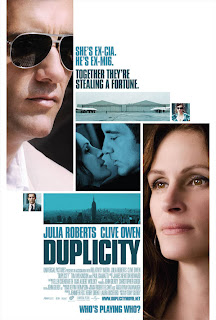

Movie Review: Duplicity

Duplicity (2009). Written and directed by Tony Gilroy. Starring Julia Roberts and Clive Owen. Excellent supporting roles by Tom Wilkinson and Paul Giamatti.

Duplicity (2009). Written and directed by Tony Gilroy. Starring Julia Roberts and Clive Owen. Excellent supporting roles by Tom Wilkinson and Paul Giamatti.

I saw Duplicity in the theaters last month in part because of the positive reviews paired with skeptical press and questions about whether Julia Roberts could still open a movie.  (Questions that angered me enough to express my opinion with my wallet, an action I believe is important.) A recent story clip on MSN compelled me to revisit the movie. The headline “Moneymakers” beside a picture of Julia Roberts, with the byline “Hollywood’s most bankable actresses” links to an article that discusses which actresses can currently be counted on to bring in the bucks. “Moneymaker”, of course, is a term most commonly associated with pornography, prostitution, and the objectification of the female ass, in particular.

(Questions that angered me enough to express my opinion with my wallet, an action I believe is important.) A recent story clip on MSN compelled me to revisit the movie. The headline “Moneymakers” beside a picture of Julia Roberts, with the byline “Hollywood’s most bankable actresses” links to an article that discusses which actresses can currently be counted on to bring in the bucks. “Moneymaker”, of course, is a term most commonly associated with pornography, prostitution, and the objectification of the female ass, in particular.

The actress-as-commodity isn’t anything unusual in the sexist institution of mainstream filmmaking, but describing a popular actress as a “moneymaker” creates a serious problem. While box office numbers (and particularly opening weekend numbers) determine a film’s success and influence executives in terms of which movies are greenlighted, I have to wonder if it’s the actress’ ass alone bringing people into theaters.

Anyhow, on to the movie.

Duplicity expects level of sophistication and intelligence from its audience, which includes the ability to follow a story that jerks viewers from location to location, and from time to time. It’s a romantic comedy, but it makes you think. Maybe this is a problem for box-office bucks, but a little mental effort makes a movie much more enjoyable–for adults, at least.

Thinking about Ripley’s Rule as a litmus test, this movie actually barely passes–if at all. This fact ordinarily is a big problem for me, but in Duplicity it feels like an afterthought. It’s a romantic comedy, but not the kind we’ve become accustomed to.  As a number of reviewers have previously mentioned, this film hearkens back to the screwball comedies of the 1940s, when wit was king, and the women generally matched the men in smarts (that’s not to say that the gender politics were a mess in those movies). What makes the movie good–and so different from other romantic comedies–is that the man and woman are on an even keel. Domination of one or the other sex isn’t the issue. These characters have bigger fish to fry–namely, their bosses in the world of corporate espionage. It’s as if Michael Clayton were remade into a romantic comedy.

As a number of reviewers have previously mentioned, this film hearkens back to the screwball comedies of the 1940s, when wit was king, and the women generally matched the men in smarts (that’s not to say that the gender politics were a mess in those movies). What makes the movie good–and so different from other romantic comedies–is that the man and woman are on an even keel. Domination of one or the other sex isn’t the issue. These characters have bigger fish to fry–namely, their bosses in the world of corporate espionage. It’s as if Michael Clayton were remade into a romantic comedy.

If you aren’t convinced that the movie is worth seeing, the opening credits present the strangest and most hilarious fight scene in recent memory.

Here’s the trailer:

Preview: Grey Gardens

This Saturday night (April 18), HBO premieres its new film version of the classic Grey Gardens. Starring Jessica Lange and Drew Barrymore as Big Edie Bouvier Beale and Little Edie, the film recreates scenes from the original documentary as well as providing the backstory of how these women came to find themselves in such a condition. Directed by Michael Sucsy.

Here’s the movie trailer:

Before it was a movie, of course, Grey Gardens was a fantastic documentary. Made in 1975 by David Maysles, Albert Maysles, Ellen Hovde, Muffie Meyer, and Susan Froemke, the film gives an unflinching portrait of two discarded members of the American aristocracy and their co-dependent relationship. The film is gorgeous, tragic, poetic, and haunting. One of my all-time favorites.

Here’s the original documentary trailer:

Finally, PBS’ Independent Lens made a film about the making of the documentary, and about the premiere of a Broadway show based on the lives of the women.

Here’s the PBS trailer:

Observe and Report Roundup

April is National Sexual Assault Awareness Month.

An odd coincidence is that Jody Hill’s Observe and Report is currently in theaters, and getting all kinds of attention for a rape scene that’s played as comedy. Worst of all, many out there are defending the movie as an edgy, dark comedy, and arguing that the scene doesn’t depict rape at all.

I’ve hesitated writing about the film; movies this noxious don’t deserve whatever free press a site like ours provides (assuming that all press is, in some way, good press). With no plans to ever see OaR, I don’t know that I could contribute a whole lot to the discussion personally, but thought I’d compile a list of what other smart people are saying, and give you a glimpse of the R-rated trailer–with hopes that it shows you as much of the movie as you’ll ever want to see.

A lot of the discussions center around the question of whether or not the sexual encounter shown in the final seconds of the trailer is actually rape. Stupid question; yes, it is. Period. The more interesting debate, which not many are taking up (according to my reading) is why a film like this is being made at this time. I’m all for dark comedy, though this doesn’t really seem like one (MaryAnn Johanson asks whether the movie is a comedy at all in her weekly column at AWFJ), and what worries me is the kind of cultural work being done. All those people who like to shout about how movies are just entertainment and say people like us have no sense of humor, or take things too seriously, are underestimating the power of representation–of the arts in general, film-making included. Although the movie has an R rating, we must ask who the intended audience of such a movie is. Clearly, it’s male, and the movie has a ring of adolescence about it (an epidemic of our time), with its “jokes” about sex, drug use, alcoholism, violence, and whatever else I’ll miss by refusing to see it, which clues us into the fact that it is for people who are still in a phase of their lives when they figure out their own values.

People are seeing OaR, too. It finished fourth in the holiday weekend box office, selling over $11 million worth of tickets. There’s a desire for this sort of thing, and the interesting question is: Why?

Here are some highlights (and lowlights) from the blogosphere:

- Friday Feminist Fuck You: Seth Rogen @ Feministing (This one has been getting lots of play, but if you haven’t seen it yet, please check it out.)

- Shorter Seth Rogen: Rape is Hilarious @ Feministe (Jill reminds us that the real trouble here is that the claim that the scene doesn’t depict a rape.)

- Observe and Report Date Rape Scene Sparks Outrage @ The Huffington Post (Be sure to vote in their poll about the scene–and prepare for the expected disappointment when you read the results. )

- Sexism Watch: Date Rape Gets Mainstream Film Release by Melissa Silverstein @ The Huffington Post (Silverstein also runs the awesome Women & Hollywood.)

- Is Date Rape Funny? Seth Rogen Explains it All for You by Margaret @ Jezebel (Quotes from interviews with Rogen and Anna Faris help you understand a little bit about the attitudes Hollywood rewards.)

- Observe & Report: On Real Rape and Um. by Sady @ Tiger Beatdown (Two well-articulated analyses on rape in this film and its impact on actual women.)

And some mainstream reviews:

- Observe and Report by Michael Phillips @ The Chicago Tribune (In a review that otherwise seems fair, writer Micheal Phillips seriously drops the ball–to say the least–when he claims: “The best, riskiest bit in Observe and Report involves Faris, with wee vomitous spillage drying on the pillow by her slack jaw, underneath Rogen, who cannot believe the dolt of his fondest desires is trashed enough to give him a toss.”)

- Mall Crisis? Call Security. Then Again, Maybe Not by Manhola Darghis for The New York Times (Darghis can be counted on as a female voice in the NYT, but she often–and this is no exception–offers more respect than is due.)

- Observe and Report by Peter Travers for Rolling Stone (The most appalling of all the “official” reviews I’ve read, which should be no great surprise, considering the source. Here’s a sample: “Props to Hill and Rogen for believing you can play anything for a hoot, including R-rated sex and violence.” Yeah–props. That’s what I was going to say.)

Other sickery:

- Writer Jody Hill describes his latest movie as “a dark, crazy, awesome journey” in “An Auteur of Awkward Strikes Again” in the NYT

- An apologist for the rape scene, in a column from New York Magazine, says:

But, given all the horrible things Ronnie does later in the movie — out of spite, or stupidity, or flat-out psychosis — this scene winds up seeming a lot less awful as the movie goes on. For one thing, as horribly misdirected as it becomes, his “courtship” of Brandi is the only thing in Ronnie’s life that comes partly from a place of sweetness rather than entirely from a place of darkness.

- And a special GFY to Bill Gibron of PopMatters, whose article “No Means Ho: Debating Observe and Report‘s Most Controversial Scene” is the worst I’ve seen, and includes gems such as:

Audiences are happy when Ronnie ends up with shy coffee girl Nell, someone who he’s built up a narrative-long relationship of openness and trust. When Brandi tries to get back in his good graces, Ronnie gives her a public kiss-off that centers on her sleeping around.

and, best of all

So which is it? Rape, or the reality of dating circa 2009? As with anything Hill has to say, the meaning is not clear. Feminists have the right to be angry, especially when a mainstream Hollywood movie offers such a backward vision of male/female fornication. But is Observe and Report really saying anything new? In this Girls Gone Wild dynamic of brazen openness and complete lack of shame, should a drunken slut bear any of the blame? It’s not a question of that horrid old excuse “she had it coming.” It’s more of a mirror on where society has sunk since women were empowered to ‘take back the night.’ Clearly, had Hill meant the scene to be something akin to pure sexual assault, Brandi would have been treated like a piece of dead meat.

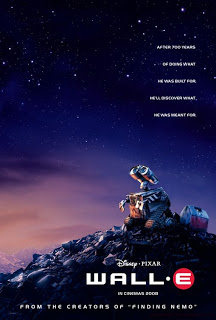

The Flick-Off: WALL-E

The Flick-Off is a new series in which we give a quick–but smart–rip to movies that tick us off.

I know, right: a rebuke of a Disney/Pixar cartoon? About robots? Yes–and it deserves it.

While the beginning of WALL-E is a lovely silent film (and would’ve been a fantastic short film), when you brush away the artifice and the adorable little robots, all you have is standard Disney fare: a male protagonist and a female helper, told from his perspective. Why the robots are gendered at all isn’t clear; the movie could’ve been about their friendship–and far more progressive than the heteronormative romance that ensues.

EVE is sleek and lovely, and is physically able to do things WALL-E cannot, but she’s part of an army of task-oriented robots. The mere push of a button shuts her down, and she lacks the self-protectionist drive that WALL-E exhibits when his power reserve drains. He is, of course, beholden to no one since the humans left Earth; he is autonomous and self-sufficient. EVE, on the other hand, is fully robotic: she’s a badass, complete with gun, and she’s more intelligent and cunning than WALL-E, but she’s been programmed to be that way. She’s an advanced form of technology, but she needs WALL-E to liberate her.

EVE is sleek and lovely, and is physically able to do things WALL-E cannot, but she’s part of an army of task-oriented robots. The mere push of a button shuts her down, and she lacks the self-protectionist drive that WALL-E exhibits when his power reserve drains. He is, of course, beholden to no one since the humans left Earth; he is autonomous and self-sufficient. EVE, on the other hand, is fully robotic: she’s a badass, complete with gun, and she’s more intelligent and cunning than WALL-E, but she’s been programmed to be that way. She’s an advanced form of technology, but she needs WALL-E to liberate her.

WALL-E, it seems, has developed human qualities on his own. He is also capable of keeping up with a robot approximately 700 years newer (read: younger) than he is–an impressive age gap in any relationship. EVE worries over WALL-E and caters to his physical limitations (he is, after all, an old man–with childlike curiosity), acting as nursemaid in addition to all-around badass. Who says we can’t be everything, ladies? While EVE doesn’t have any of the conventional trappings of femininity, she’s a lovely modern contraption with clean lines, while WALL-E is clunky, schlubby, and falling apart (not to mention he’s a clean rip-off of Short Circuit‘s Johnny 5)–reinforcing the (male) appreciation of a certain kind of female aesthetic, while reminding girls that they should look good and not worry too much about the appearance of their male love-interest.

Pixar, by the way, hasn’t created a female protagonist yet.

More contrary opinions about WALL-E–including the troubling way it portrays obesity–on:

If you know of some other good discussions on the film, leave your links in the comments.

Short Review: Los Ojos de Alicia

Los Ojos de Alicia (2005). Written and directed by Hugo Sanz. In Spanish (no English subtitles).

I saw the short film Los Ojos de Alicia as part of the Cincinnati World Cinema 8th annual “Oscar Shorts,” which screens this year’s nominated short films, along with ‘bonus’ films (of which this is one; I’m not privy to the selection process of the bonus films).

Of the eight films (in Part B of the program), I’m sad to say that not one passes the Bechdel test. Los Ojos de Alicia (which you can–and should–watch in its entirety above, although it is in Spanish without subtitles) comes closest, as it stars a woman and a video recording of a woman talking to her–although it turns out to be the same woman, talking to herself. (Note: if anyone can provide an English transcript of the film, please let me know.)

We open on a woman, tied up and blindfolded, just waking from a memory-erasing procedure. A recording turns on and a woman leads the blindfolded woman to a glass of apple juice to quench her thirst, then tells her the juice is poison. She tells the still-hooded woman exactly what memory she’s had erased: the woman returned home to find her husband seriously wounded and bleeding to death. She stopped to care for him before checking on her daughter, who she found also seriously wounded and who soon died. Not only did the woman choose her husband over her child, but she then learned that her husband stabbed the child, before trying to kill himself. The woman doesn’t know how to live with the implications of the tragedy, which led her to this room. The woman in the recording tells her there’s an antidote to the poison juice, if she can just cut herself free and swallow a pill. Just before the woman swallows the pill, we learn that it’s the pill–not the juice–that contains deadly poison. The woman in the video challenges her will to live in the face of the tragedy she experienced.

I think the film was included because it is provocative and good for engaging conversation, though the format of the festival (one film right after the next) did not encourage discussion. However, it bothers me on multiple levels. We have a male writer and director pontificating on a woman’s guilt, remorse, and what can only be described as self-hatred. This is a torture film, even if it is self-torture.

It’s interesting to consider how we deal with tragedy, though the thesis here seems to be that the only way past it (or through it) is to create an even more horrific tragedy. I can see how a woman would want to punish herself for failing to save her child, even when it’s not in any way her fault. What I like about the film is that it literalizes the way we torture ourselves when we feel we’re to blame for something terrible. The act of making literal torture in a raw and painful way makes us think about the banal torture people inflict on themselves. We all know someone who has been through unspeakable tragedy, and many times what the person does to herself (or himself) amounts to destruction on a tragic level.

What I don’t like about the film is its manipulation. It feels very much like cheating to create a universe in which we have alternate reality (memory erasure) and still are supposed to feel sympathy for a woman who would choose to do this to herself. We don’t know if the memory-erasure was a success; even with the juice detail (the woman claimed to enjoy the apple juice, even though we’re told she hated apples as a child) we just don’t know what kind of memory she has of what happened. She saves herself, but not without first forcing the “new” her to have a (false?) memory of what she lived through. Ultimately, the film is manipulative and sadistic; a thought-experiment on suicide, but not a very productive one.

Here is the CWC program of Oscar Shorts, Part B:

- Auf der Strecke (On the Line)

- This Way Up

- Los Ojos de Alicia

- Presto

- Spielzeugland (Toyland) – Live Action Short Oscar winner

- Lavatory – Lovestory

- Sintonia

Bitch Flicks’ First Anniversary

Today marks the first anniversary of our site, and of our first post. If you want to know what Bitch Flicks is all about, go back and read our manifesto. Things said a year ago still ring true, and the need for women to engage in conversation about film and feminism certainly hasn’t decreased.

A big thanks to readers who have linked to the site.

Continuing with the project is much easier when we know people are reading–and responding to–our ideas. If you’ve linked to us and we haven’t noticed, let us know who you are.

We’d love to hear more from our readers, and encourage lurkers to comment. More voices mean better conversations. We moderate, but only to weed out the trolls.

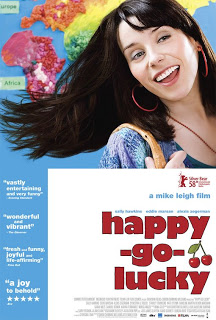

Ripley’s Pick: Happy-Go-Lucky

Happy-Go-Lucky. Starring Sally Hawkins, Alexis Zegerman, Kate O’Flynn, Sarah Niles, and Eddie Marsan. Written and directed by Mike Leigh.

Poppy Cross (Hawkins, who won a Golden Globe for her performance) is a 30-year-old primary school teacher in London. She shares her flat with her roommate of ten years and lives a life filled with happiness. What feels at first like an innocent, fluff-filled movie is actually an examination of the difficulty of living life with a goal of happiness.

Time after time, Poppy’s optimistic outlook on life is tested. A rude worker in a bookshop doesn’t respond to her small talk, someone steals her bicycle, she injures her back, and her new driving instructor (Marsan) has what you could call a serious dark streak. Instead of reacting cynically, Poppy struggles to stay positive and, what’s more, create moments of happiness in the lives of others.

Effective teaching is a major theme of the film. Scott (her driving instructor) talks about the necessity of repetition in teaching, we see multiple scenes of Poppy and Zoe interacting with their young students, and we see a fantastic scene with a flamenco instructor who channels her heartbreak into passionate instruction. If ever there was a profession that requires optimism, Poppy—with her bold, confident, and fearless personality—makes a great spokesperson.

Scott (her driving instructor) talks about the necessity of repetition in teaching, we see multiple scenes of Poppy and Zoe interacting with their young students, and we see a fantastic scene with a flamenco instructor who channels her heartbreak into passionate instruction. If ever there was a profession that requires optimism, Poppy—with her bold, confident, and fearless personality—makes a great spokesperson.

Perhaps the greatest struggle Poppy faces is the force of the status quo. Her outlook on life, which she shares with her friends and one sister, is summed up nicely by friend and coworker Tash (Niles), who relates what she tells her prodding aunts:

“No, I haven’t got a boyfriend. No, I won’t be getting married soon, and, no, I won’t be investing in a property with a mortgage in the near future, thank you very much.”

Amen, sister. The movie actually spends little time on social forces driving women, particularly, to settle down  (except for one visit to the ‘burbs), though this always lurks in the background. The bigger struggles are the everyday events that drag us down, which makes this a nice little slice-of-life movie, with a minimal plot, and a major focus on character. Female friendship is at its heart, without the stock shopping and food footage that most films use to represent how women bond. As we know, bonding over consumption of material objects (whether they be chocolate, sexual conquests, or clothing) forms the most shallow of relationships. Happy-Go-Lucky is a film that realizes this fact.

(except for one visit to the ‘burbs), though this always lurks in the background. The bigger struggles are the everyday events that drag us down, which makes this a nice little slice-of-life movie, with a minimal plot, and a major focus on character. Female friendship is at its heart, without the stock shopping and food footage that most films use to represent how women bond. As we know, bonding over consumption of material objects (whether they be chocolate, sexual conquests, or clothing) forms the most shallow of relationships. Happy-Go-Lucky is a film that realizes this fact.

Once you adjust to Poppy’s infectious (or, I found, slightly grating) personality, you’ll see a female-centered movie that just leaves you feeling good. Oh, and you’ll forever have Enraha. You’ll understand if you’ve seen it; that one sticks with you.

Movies We Won’t Review: Miss March and I Love You, Man

It’s not that we have anything against male-centered movies, it’s just that we have better things to do. These two, in particular, inspire staying home and saving our money. Check out what other female critics have to say.

I Love You, Man

MaryAnn Johanson of FlickFilosopher: Conform, Man, Conform

Renee Scolaro Mora of PopMatters: Man dating.

Betsy Sharkey of L.A. Times: Paul Rudd and Jason Segel star in a bromantic comedy that leaves behind any hope for some heart.

Miss March

Stephanie Zacharek of Salon.com: The comedians behind “The Whitest Kids U’ Know” cram their film debut with boobs and poo jokes — but end up with a serious stinker.

MaryAnn Johanson of FlickFilosopher (again): Virgin/Whore: The Movie

Rachel Saltz of The New York Times: Centerfold Sentiments

A Big WTF to the NYT

Published in the New York Times on Saturday, March 20, “An Entourage of Their Own” by Deborah Schoeneman, highlights the friendship of four women writing in Hollywood today: Dana Fox, who wrote What Happens in Vegas and the screenplay for The Wedding Date; Diablo Cody, who wrote (and won the Oscar for) Juno, the upcoming Jennifer’s Body, and the Showtime series The United States of Tara; Liz Meriwether, who is beginning a screenwriting career after a successful run as a playwright in NYC; and Lorene Scafaria, wrote the screenplay for Nick and Nora’s Infinite Playlist.

Here’s what’s great about the article: In these writers, we have four talented women who give us a positive model of the power of female solidarity, especially in an industry not known for such behavior. In the mode of ‘all publicity is good publicity,’ the article brings attention to women working in Hollywood, and wants to be about how these women navigate life, work, and success in a deeply sexist industry.

Here’s the trouble: “An Entourage of Their Own” appears in the Fashion & Style section.

Why are we reading a fashion article about these women? Especially when there’s very little discussion of fashion or personal style?

Okay, so the four women—who happen to be screenwriters in an industry hostile (at the very least) to powerful women—have a certain kind of style that is more hipster than glam…we guess. Fine. But the way the (female!) writer depicts these women, using the language of submissive sexuality, is atrocious.

Take the opening paragraph:

Cross-legged in one director’s chair was Lorene Scafaria — black pants, brown high heels, amused gaze — leaning in to ask the next question. Waiting to answer, cross-legged in another, was Diablo Cody, struggling to keep her short blue dress from riding up.

This is a style piece (and lifestyle, to be more exact), but why the need to immediately objectify—and sexualize—the women, particularly Cody, with her near-exposure? The first four paragraphs include “cross-legged,” “crossed legs,” “gaze,” “leaning in,” “struggling,” “short blue dress,” “riding up,” “gorgeous,” “naked,” “plunged,” “revealing,” “intimate glimpse,” and “nudity.” At this point, readers are not thinking about fashion or style–much less what they’re interested in writing about–we’re thinking about these women as sexualized objects.

The writer is quick to remind us how hard they work, and how few women can achieve their level of success (!) in Hollywood, and how that success can’t be attributed to their looks, but, just as quickly, she undermines their hard work by quoting men in the biz.

“When you read a screenplay, it doesn’t come with a picture on the cover,” said Adam Siegel, president of Marc Platt Productions, a producer who is friends with all four women and has worked with all except Ms. Cody. “I know a few beautiful women, but none of them write like Dana, Liz, Lorene or Diablo.”

What, exactly, does beauty have to do with writing? If their success cannot be attributed to their good looks, why the incessant need to talk about it? Why is coverage of female filmmakers relegated to the style section of the paper? Finally, if we’re going to have a style piece about the “Fempire,” how about some discussion of their personal style and the way it reflects their confidence, or how it differs from other women who have achieved a similar level of success and power in Hollywood?