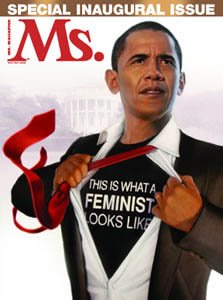

Representing President Obama as a “Super-feminist” has ignited a debate over who the savior of feminism ought to be (see here for a good overview), and likely sold a lot of copies of Ms. magazine’s January edition. Praise for the new president’s political aspirations regarding women’s rights isn’t contended; it’s how the feminist magazine chose to portray Obama: tearing open his Clark Kent clothes to swoop in and rescue us. It’s the representation that has people peeved.

For our purposes here at BF, two articles were published last month–the weekend before the inauguration–about the impact the movies had on Obama’s election. Not that the movies got him elected, but how roles black American men play in the movies have a real effect on the people who see them, and how we can see, through the movies, our own cultural values reflected back on us.

If you ever question how important representation in film really is, I think these articles make the point well. While they specifically focus on male presidential aspirations (and on the unique history of black Americans), they also remind us how pop culture permeates our society and informs opinions and values.

The New York Times published “How the Movies Made a President,”written by A.O. Scott and Manhola Dargis, in their Film section. The article provides an overview of black male roles, from the “Black Everyman” of the ’60s to the “Black Messiah,” currently played and re-played by Will Smith.

Make no mistake: Hollywood’s historic refusal to embrace black artists and its insistence on racist caricatures and stereotypes linger to this day. Yet in the past 50 years — or, to be precise, in the 47 years since Mr. Obama was born — black men in the movies have traveled from the ghetto to the boardroom, from supporting roles in kitchens, liveries and social-problem movies to the rarefied summit of the Hollywood A-list. In those years the movies have helped images of black popular life emerge from behind what W. E. B. Du Bois called “a vast veil,” creating public spaces in which we could glimpse who we are and what we might become.

We hear from the likes of Elizabeth Banks and Katherine Heigl that the only roles really open to them—genuinely talented, lovely young actresses—are that of sidekick, buddy, and romantic object. It’s not that there haven’t been good, meaty roles for women; there have, for sure. But what movie roles do young girls imitate? What fictional figures can women look up to?

The Root’s “Hollywood’s Leading Man: From Sammy Davis Jr. to Dave Chappelle’s Black Bush, how pop culture tested the waters for a black president” offers a more nuanced and contrarian view of the power of pop culture (and reminds us of the egos of those who really believe their art makes a difference). The article surveys the satirical representations of a black president as representative of the racial divide in America, but cites the series 24 as a shift–although one not without its problems–and questions how television and cinema will change.

So now that we have a black president, how will we react to media portrayals? Will there be pressure among writers and producers to create black leaders who feel real and black-led administrations that feel plausible? Will we, as viewers, be able to enjoy over-the-top portrayals of black presidents, such as Terry Crews’ wig-wearing wrestler in Idiocracy, as merely fun entertainment, devoid of racial and social commentary?

Might we perhaps see a black actor playing the lead in a complex drama like The West Wing, or a romantic comedy along An American President, where the president gets to be a fully fleshed out human, and not a cardboard icon? And isn’t it about time that we saw a portrayal of an African-American president who just happens to be a woman, too?

I, too, would like to see that woman. And I think we’d all like to see her on the cover of Ms., wearing a t-shirt that reads “This is what a feminist looks like.”