Two men hanging in the ultimate man cave, drinking beers, talking about how “fucking amazing” the woman in question really is. One lifts weights, pounds liquor, and then detoxes for a few days. The other is invited to be the buddy, the wing man on a journey to encounter women. While watching Ex Machina, I couldn’t help feeling like I was watching a buddy pic like The Hangover–just some bros hanging in their crib, considering women. A few days into the week, a hot Asian woman appears out of nowhere, fulfilling their desires for food and–for Nathan–sex. Kyoko is the perfect woman: she doesn’t speak; she just serves.

But when Nathan and Caleb are discussing the woman of greater interest, Ava, they use coding jargon to analyze her language capabilities. It is not that they are interested in her for her brain; they are interested in her for her “brain,” if her artificial intelligence can pass the Turing Test and convince the men that she is a woman.

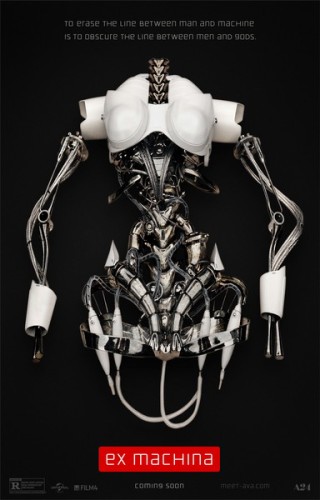

Ava looks like a girl child, a nymph. Viewers first see her silhouette, her breasts and ass covered with metal sheeting; otherwise, we can see right through her into her circuits. We watch her through the same glass through which Caleb will watch her. She is encapsulated in the fortress Nathan has made for her, a glass fortress that boasts cracks from unexplained incidents.

When Caleb, invited to visit the research facility as the winner of a (SPOILER–and this will be your last warning) constructed contest, first meets Ava, he is in awe of her language capabilities, the first baseline he uses to determine her viability as a “human.” She tells him, “I always knew how to speak,” then asking if that is odd. They have a heady-ish discussion of linguistics before he has to leave the session.

Caleb soon discovers that the only channel on his TV is the “spy on Ava” channel. At first he is disgusted, but it doesn’t take long for him to have it on while he is dressing. Ava–sweet, constructed, feeling–does not know she is being watched. Nathan takes Caleb on a tour of his workshop where he creates only female models. They spend most of the conversation marveling at her “brain,” the constructed machinery that gives her thought and feeling.

However, the week progresses, and quickly the talk turns away from her intelligence to whether or not she is fuckable after Ava asks Caleb if he is attracted to her. Caleb and Nathan sit next to each other to discuss her gender and sexuality, terms that they incorrectly elide. For men so interested in constructs, one would think they would get these two straight. From this point on, the film focuses on her body and its uses. In his brusque way, Nathan pronounces, “You bet she can fuck,” answering the question Caleb has been pondering but won’t ask. Nathan continues: “I programmed her to be heterosexual.” He tells Caleb that she has an “opening” with “sensors” that allows her to feel physical pleasure. He does not use the word vagina, eschewing her humanity–or questioned humanity–making it all about the hole that they can penetrate.

Meanwhile, Ava is using her body to create power surges that allow her to speak freely with Caleb about her desire to see the outside world. She would spend time on a street corner watching the humans interact with each other. Caleb is taken with becoming her hero. To him she is the damsel in distress; to Nathan she is the daughter. The former chivalrous, the latter paternalistic: both are complicit in her creation and entrapment. Caleb’s determination of her viability will do nothing to save Ava from Nathan’s desire to reboot and update her model.

And for this, they both must die.

Through a derring-do of masculinity, the men end up working against each other and orchestrating each other’s death, both at the hands of Ava and Kyoko, part of an A.I. army of sexy female models enclosed in Nathan’s room. Ava benefits from Kyoko’s quickness with her chef’s knife, deftly stabbed into Nathan’s back.

Ava benefits from Nathan’s diabolical need for privacy in his subterranean lair with computer-operated, hermetically sealed doors. Ava has no pity for her knight in shining armor now screaming in panic to be left to die. Those that have constructed her and desired her have been used–she is ready to go out into the world they have denied her. Caleb is not an innocent; he wants to save her so he can have her for himself. He wants her as a partner and lover; he is not simply interested in freeing her for the good of her humanity.

Ava then goes to the other “women.” I thought she would free them all in an act of feminist collectivity, a liberating moment for the women that have been enslaved in sexual service to Nathan in his lair where no other humans visit. He has surrounded himself with “yes”-women, all thin, gorgeous, naked in storage waiting for his needs to call them out.

But she doesn’t free them. Instead, she acts as a scavenger, taking parts from each woman to create herself. An arm from one, hair from a second, a pristine white dress from a third. For Ava is not naïve; she is about to enter a world of patriarchal capitalism, and in order to survive, she must take from other women, not give. The moment for collectivism is lost as Ava chooses to free herself as a whole woman, gorgeous and nubile. She leaves the other women behind, broken and lifeless in their pens. Her artificial intelligence has given her enough knowledge to understand that the world she is entering requires a denial of others’ needs; in that understanding, she is a perfect subject in the capitalist system, and her lack of humanity helps her disavow the compassion that gets in the way of such systems. Ava greets the helicopter meant to airlift Caleb back to his life; she wears stilettos and carries a purse, about to greet the world she has wished to enter, a trace of destroyed souls and “souls” left in the wake of her desire to survive.