|

| Filmmaker Jillian Corsie |

Author: Bitch Flicks

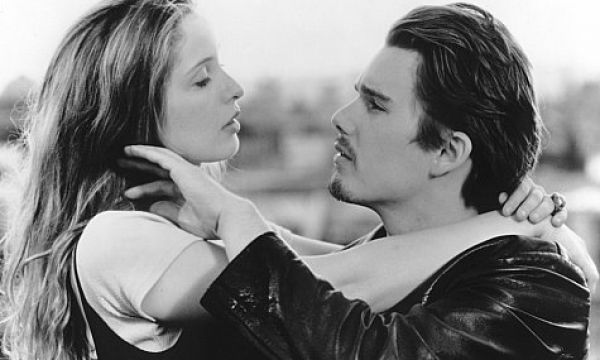

The Flattening of Celine: How ‘Before Midnight’ Reduces a Feminist Icon

Call for Writers: Representations of Women with Disabilities in Film and TV

In movies, on TV or in novels, physically disabled characters are rarely the protagonists. Rather, the disability is the catalyst which propels the main character–generally a photogenic, able-bodied person–to act/react/grow/save/emote/empathize. The token disabled person serves one dramatic purpose: moral impetus for the hero.

Away from Her

Dancer in the Dark

Babel

Homeland

Silver Linings Playbook

The Miracle Worker

Sybil

Girl, Interrupted

Curb Your Enthusiasm

The Other Sister

The Secret Life of Bees

The Piano

Benny & Joon

Push Girls

Love and Other Drugs

Phoebe in Wonderland

Million Dollar Baby

Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?

United States of Tara

Frida

Orphan

My Sister’s Keeper

An Affair to Remember

Glee

Pauline & Paulette

Blue Sky

Children of a Lesser God

Frances

Grey’s Anatomy

The Horse Whisperer

Iris

Molly

‘Night Mother

Girls

Return to Me

Steel Magnolias

The Three Faces of Eve

The Guild

Wait Until Dark

Passion Fish

Soul Surfer

My Gimpy Life

The Ten Most-Read Posts from May 2013

Did you miss these popular posts on Bitch Flicks? If so, here’s your chance to catch up.

“Is Pepper Potts No Longer the ‘Damsel in Distress’ in Iron Man 3?” by Megan Kearns

“Does Uhura’s Empowerment Negate Sexism in Star Trek Into Darkness?” by Megan Kearns

“Star Trek Into Darkness: Where Are the Women?” by Amanda Rodriguez

“Stoker and the Feminist Female Serial Killer” by Amanda Rodriguez

“The Occasional Purposeful Nudity on Game of Thrones“ by Lady T

“Let’s Re-Brand ‘Disney Princesses’ as ‘Disney Heroines'” by Robin Hitchcock

“Girl Rising: What Can We Do to Help Girls? Ask Liam Neeson.” by Colleen Lutz Clemens

“Oblivious Hollywood and Its New Movie Oblivion“ by Rachel Redfern

“Choose Your Own Sexist Adventure: Victim Blaming, Domestic Violence, and the Glorification of the Nice Guy™in Mud“ by Stephanie Rogers

“Sex and the City 2: Hardcore Orientalism in the Desert of Abu Dhabi” by Emily Contois

Wedding Week: "You Were Dead Until Now": A Review of ‘Bride Wars’

This is the wrong film for the wrong times. Sure, folks like to go to the cinema to escape their troubles. (Think of all the musicals and frothy comedies that were released during the Great Depression.) But in these dark economic times, watching two gorgeous, skinny, screeching young women battle over their insanely lavish weddings–no thanks. This stuff would have seem tired and sexist 40 years ago, let alone in 2009.

Ece Okar currently lives in Asheville, NC. She is working part time at a local community college as well as Helpmate, a great nonprofit where domestic violence victims can turn to for counseling, education, and shelter. She is working toward going back to school to get her MSW so she can help people suffering with mental health and substance abuse issues.

Wedding Week: You’re Nobody Till Somebody Loves You: ‘Muriel’s Wedding’ and the Promise of Bridal Transformation

|

| Muriel depressed at home |

Muriel Heslop (Collette, in her first major role) has very little going for her as a wedding movie heroine. According to her friends from her banal suburban hometown of Porpoise Spit, Australia, she is beyond help—as one of them tells her, “You never wear the right clothes. You’re fat. You listen to 70s’ music. You bring us down, Muriel. You embarrass us.” Even if their criticisms are over the top, it’s plain that Muriel is uncomfortable in her own skin—the only moment where she looks relaxed is when she tunes out to Abba music in her bedroom, the walls of which are plastered with pages torn from bridal magazines. “I know I’m not normal,” she says to her bitchy friends, “but I’m trying to change.” “You’ll still be you,” they counter.

|

| Muriel at resort |

Their criticisms sting as badly as those from her father (Bill Hunter) a local celebrity clinging to his former political glory and doling out heavy psychological abuse to everyone in his family, including his meek and scatterbrained wife Betty (Jeanine Drynan, in a heartbreaking and subtle performance). Muriel yearns to escape from Porpoise Spit, and when her father’s mistress snags her a job as a cosmetics saleswoman, she cashes in her start-up money for a resort vacation to spite her old friends. There she reconnects with a former high school classmate Rhonda (Griffiths), who is nothing like Muriel’s former crowd.

|

| Rachel Griffiths as Rhonda |

Watching Rhonda and Muriel’s first conversation, you can see Muriel peeking out of her shell, as a brand new friend expresses real interest and enthusiasm in her life. Rhonda tells it like it is—she delivers the swift kick to the groin that the terrible Porpoise Spit girls deserve, and we immediately see what a friend like her does to liberate Muriel’s sense of self and fun. Is there anything more satisfying than watching Muriel and Rhonda triumph with their Abba number while the girls tear each other apart?

This is what triumph looks like—not a march down the aisle (we’ll get there later), but a victory dance with someone who matches you, white lame costume and all. The most romantic moment in the movie isn’t between Muriel and her new husband, it’s between Rhonda and Muriel as they celebrate their last night at the resort. Rhonda genuinely admires Muriel—partly for Muriel’s lie about a fiancé, but mostly because she is starting to stand up for herself. “In high school, you were so quiet you could hardly talk,” Rhonda tells her. “You were too shy to look at people . . . You’re not nothing, Muriel. You’ve made it.”

|

| Rhonda and Muriel |

It takes making a true friend like Rhonda to get her to leave her parents’ house and strike out for Sydney, where she gets a job as a video store clerk (right across the street from Rhonda’s job), finds a bit more of her own style, and begins dating. “This is my new life, I’m a new person—I’m changing my name, to Mariel.” Muriel/Mariel finds herself leaping fully into life—and into romance, without hesitating or fearing embarrassment. Even her first sexual encounter is full of joy—especially when she realizes the guy is even more eager to please than she is.

For a brief period, Muriel doesn’t count on Abba or wedding photos to feel good about herself. “Since I’ve met you and moved to Sydney, I haven’t listened to one Abba song,” she tells Rhonda. “That’s because now my life’s as good as an Abba song. It’s as good as ‘Dancing Queen’.” This confidence wanes, however, when Rhonda gets a scary diagnosis that leaves her in a wheelchair. Despondent, Muriel stops into a nearby bridal salon in hopes of comfort, in one of the most fetishistic wedding dress scenes of all time.

|

| Muriel in wedding dress |

Muriel’s yearning is palpable—she tears up as she’s swathed in silk, completely obsessed with the vision of herself as a beautiful bride. The illusion of desirability is enough to make her happy—for Muriel seeks transformation above all, the ability to feel beautiful and loved and to become Mariel, a bride, anyone except her old self.

When that transformative wedding presents itself, Muriel seizes the opportunity—even if it means marrying a foreign Olympic-level swimmer, David van Arkle (Daniel Lapaine), to help him gain citizenship. The marriage is predicated on a lie, and yet Muriel slips into the arrangement willingly, trading perfect love for a perfect wedding. Because she has such an extreme investment in this new version of herself, she leaves Rhonda behind, and as she walks down the aisle at her wedding (to an Abba tune, of course), she grins so broadly that she looks maniacal.

The wedding, in Muriel’s eyes, is a triumph—but when Rhonda, wheelchair-bound and stuck back in Porpoise Spit confronts her, the victory is suddenly very hollow. “I showed them,” Muriel beams. “Showed them what?” Rhonda asks. Muriel replies, “I’m as good as they are.” Rhonda is appalled. “Mariel van Arkle stinks. And she’s not half the person Muriel Heslop was.”

|

| Muriel at altar |

What is marriage supposed to do for a woman who doesn’t know her worth? Does a wedding dress make an ugly person beautiful? Does speaking vows equal promising love? Muriel epitomizes the kind of person who, in lieu of other prospects in her life, waits for the transformative power of her wedding day to find her true self. But this self wasn’t the one who blossomed with Rhonda and a new city—Muriel wanted to have the same success as that of her old friends, to be called successful because she had the marriage and the new name and the status of a beautiful wedding. But on her first night as a married woman, she sleeps alone, her husband a stranger, her friends all absent.

|

| Betty (Muriel’s mom) |

Muriel’s Wedding is basically a cautionary tale about valuing status and reputation over real connection. Muriel knows that she’s happy with Rhonda in Sydney, but by fulfilling her fantasies of beauty, wealth, and romantic achievement, she forgets her real strength: her honesty, decency, and kindness. These strengths were all there in her mother, Betty, whose cruel fate turns the movie from a girly romp into something much more meditative. She is talked over, pushed around, and utterly ignored, invisible even in her own home. Betty barely gets a moment of self-determination before she commits suicide, and her presence is felt most deeply in the frightening image of the Heslop backyard: a swath of literally scorched earth, where nothing can grow if nothing is tended and cared for.

|

| Muriel in bed |

Early in the film, Muriel tells her mom, “I’m gonna get married, and I’m gonna be a success.” And yet, weeping to her unfamiliar husband, Muriel realizes that her success is as thin and insubstantial as bridal organza. Speaking of her father, Muriel wails, “I thought I was so different—a new person. But I’m not. I’m just the same as him.” It takes retreating back to her true self, to calling herself Muriel once more, to actually feel loved, beautiful, and ready to take on the world. And Hogan delivers a finale that satisfies all those cravings.

So ultimately putting Muriel’s Wedding in the wedding movie category is a bit like calling Thelma and Louise a crime thriller. Because the film skewers the narrow way a woman can view her wedding as a Cinderella-like escape, it may be one of the sharpest and smartest satires of our wedding-obsessed culture ever captured on film—and one of the best female empowerment movies ever made. While Muriel may have been a beautiful bride, she makes an even better heroine for single, married, and engaged women everywhere when she ditches the veil, the bouquet, and the bridesmaids, and finally learns to rely on herself.

|

| Muriel at end |

Wedding Week: Bigger Than Big: Marriage and Female Bonding in ‘Sex and the City: The Movie’

For those of us who followed the girls on the hit HBO series, Sex and the City: The Movie, directed by Michael Patrick King, was a hotly anticipated film by the time it was released in 2008. We are familiar with Carrie as an avid writer, a New York fashionista, and an independent woman who consistently shies away from marriage. Certainly, Carrie’s disinterest in marriage throughout the show’s run can be interpreted as feminist by audiences. However, Carrie is quickly swept up in pre-matrimonial hysteria such as her designer dress and guest list. Big tells Carrie repeatedly throughout the film, “I want you,” as opposed to the desire for an extravagant wedding, but this sentiment seems to fall on deaf ears. The underlying message–and it’s a feminist one–seems to be this: smart girls don’t fall in love, smart girls love themselves. We meet Carrie as a woman who is attempting to negotiate these two philosophies, and by the end of the film, Carrie successfully marries Big but also prioritizes herself. In fact, her talk of marriage with Big originates from her drive for self-preservation. In reference to their swanky new apartment, she tells Big, “I want it to be…ours,” rather than his.

|

|

Carrie marks her territory at “Heaven on Fifth,” as she calls it.

|

“I wouldn’t mind being married to you. Would you mind being married to me?” Big casually questions as the pair prepare dinner. Carrie requests a “really big closet” in lieu of a diamond ring, a somewhat radical move that breaks with tradition as well as the stereotype that many women are “gold diggers” who equate a man’s commitment to the size of the rock he offers her. Rather, Carrie is financially equipped to find and purchase a diamond herself if she decides she’d like one. Carrie neither supports nor challenges the concept of marriage; throughout six seasons of Sex and the City on HBO, Carrie finds that marriage doesn’t suit her and she’d rather not play the role of wife. She tells Samantha, “There’s no cliché, romantic, kneeling on one knee, it’s just two grown-ups making a decision about spending their lives together.” However, Big does kneel down on one knee to formally propose inside “Heaven on Fifth’s” walk-in closet. In this space he builds, Big is “making room” for his bride, and this act of creation is at once romantic and understated. For Carrie, this gift is paramount in Big demonstrating his commitment to her, but hasn’t he already done so in a multitude of other ways?

|

| Contrary to Charlotte’s engagement party toast, Big remains grounded in reality as Carrie is the one “Carried away.” |

|

| Charlotte is a spokesperson for the joys and functionality of marriage within a heteronormative lifestyle, complete with the nuclear family by the film’s conclusion. |

|

| It’s not marriage that can “ruin everything,” but over-the-top weddings: rituals that become more significant than the love, support, and sacrifice they symbolize. |

Bringing the gang on her honeymoon is a decidedly feminist move on Carrie’s part; they are her support system and her surrogate lovers while she and Big are separated. Samantha even spoon-feeds her in bed as Carrie’s being “jilted” at the altar effectively infantilizes her while in Mexico. When audiences observe this pathetic and uncomfortable scene, we are confronted with the notion that, along with Miranda, Samantha has transformed into a maternal character while Carrie grieves. This is undoubtedly the closest Samantha will ever come to motherhood. “Will I ever laugh again?” Carrie asks, and of course, it’s when Charlotte shits her pants. The girls are a reliable source of Carrie’s happiness and stability, a reflection of who she is rather than who she wants to be. Unlike the second movie, in which the gang travels to Abu Dhabi, Samantha is more invested in her friend’s wellbeing than having sex with random men.

|

| Samantha happily mothers Carrie at her low point, and even winks at her as she stirs her food. |

When Carrie returns from Mexico, she takes on an assistant, and it becomes noticeable that Louise (Jennifer Hudson) is the only black character in the film, a surprising detail given that the setting is New York City. In fact, when searching for a new apartment with her son and nanny, Miranda excitedly says, “Look! White guy with a baby! Wherever he’s going, that’s where we need to be.” Is it me or is this line inextricably offensive? A white man carrying a child is highly symbolic of traditional heteronormative values. Together, these alarming observations render the film both racist and classist. Miranda’s in search of an upscale, and thus white, neighborhood that’s safe for her son.

|

| The poor colored girl from St. Louis is new to the luxury of owning as opposed to renting. |

On Halloween, Charlotte suggests to her adopted Chinese daughter, Lily, that she can be Mulan for Halloween, but Lily instead chooses to be Cinderella. Even at her young age, Lily embraces whiteness as a beauty ideal and is more stimulated by the glamour of ball gowns and being rescued by a handsome prince than battle armor and the spoils of war. Seemingly, the fantastical princess narrative trumps a feminist warrior’s tale, at least for a girl young enough to still believe in “happily ever after.”

|

| The laughably mismatched trick-or-treat crew serves as comic relief amidst scenes of loneliness and heartache. |

|

| The meter is literally running on the pair’s friendship as Miranda’s confrontation of Carrie serves as a reflection of her own personal and marital flaws. |

It is only once Carrie has made peace with Miranda that she can move forward to reconcile with Big. “There is no right time to tell me that you ruined my marriage,” she spits at Miranda on Valentine’s Day. In fact, there is no marriage to destroy since Big failed to show up. However, the marriage and harmonizing of the four friends is climactic within the film’s plot while Carrie’s marriage to Big takes place almost as an afterthought, part of the film’s resolution.

|

| We are given the elusive image of Carrie barefoot, sans designer stilettos. |

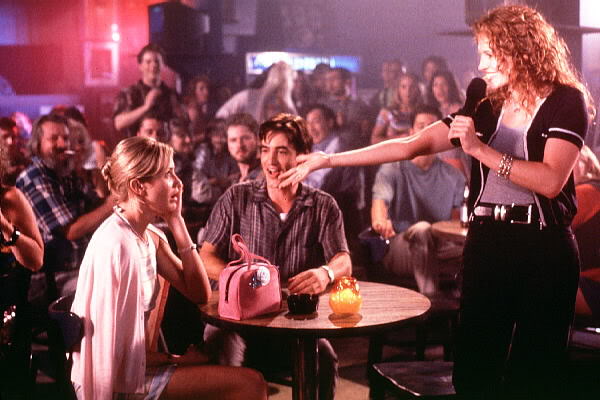

Wedding Week: ‘My Best Friend’s Wedding’ Is a Right-Wing Nightmare Interpretation of Women

|

| Julia Roberts in My Best Friend’s Wedding |

|

| Someone nicely made a collage of all this. |

|

| Julianne cruelly forces a terrified Kimmy into singing karaoke. |

|

| “It’s amazing the clarity that comes with psychotic jealousy,” George says to Julianne. |

|

| Kimmy confronts Julianne in the ladies room where we are reminded that POC do exist. |

Wedding Week: ‘Sex and the City’: The Movie We Hate to Love

Wedding Week: ‘Shrek’: Happily Ever After Gets a Green Makeover

|

| Princess Fiona |

This is a guest post by Megan Wright.

When I first watched Shrek, I can’t really remember how I felt about Fiona, aside from the fact that I thought it was fantastic that she was fighting Robin Hood and his Merry Men. As the years passed, I bought the movie, and it was also broadcasted on several channels. It was almost impossible to go a year without seeing it. So, as I watched it more and more, I could figure out the underlying themes in Shrek: appearances don’t matter, the locking away of those perceived as different is wrong, and that talking donkeys are awesome. But the most important theme of the movie is how a strong woman almost gets tricked into a loveless marriage because of her low self worth, all due to the standards of beauty society imposes on her.

I’m talking, of course, about Princess Fiona. Fiona is meant to be a deliberate contrast to the stereotypical princess. Her elaborate way of talking is forgotten in favor of insulting Shrek. When Robin Hood tries to rescue/abduct her, she promptly beats the crap out of him. She sings, but when she does, she accidentally blows up a bird. During her years in a tower, Fiona hasn’t simply gazed out a window, but instead taught herself first aid and martial arts. She doesn’t take Shrek’s plan to get her back to Farquaad happily. When Shrek complains that it’s his job, she replies “Well, I’m sorry, but your job is not my problem.” She knows the way she wants this rescue to go, damn it, and she’s not going to go along with Shrek’s plans simply to make it easier on him.

|

| Princess Fiona, not in Ogre form |

So why does she get bullied into marrying Farquaad?

The problem is that Fiona lives in a world that tries to separate anyone who doesn’t fit the ideal representation of perfection. Lord Farquaad first talks about it, saying that the fairytale creatures are ruining his “perfect kingdom.” Shrek shows a world that really isn’t too different from our own. Sure, the segregated group includes talking pigs, wolves that enjoy dressing like grandmothers, witches riding on broomsticks, but their problems are still similar. The fairytale creatures are kicked off their land and moved into an inhospitable area (Shrek’s swamp) simply because they don’t fit the norms of Farquaad’s perfect kingdom. It’s not that far off from real world situations.

Here’s an example of how much beauty means in this world–in the beginning of the movie Farquaad uses a magic mirror and is given a list of several princesses to choose from to make into a queen. One of those princesses is Snow White, who later shows up in Shrek’s swamp, exiled with the dwarfs. This sends the message that if magic can help him obtain a beautiful wife, then he’s fine with it. It’s only the “undesirable” fairytale creatures that we see Farquaad hates. Throughout the movie we think that Farquaad hates fairytale creatures, but he doesn’t. He hates the fairytale creatures that don’t match up to his obsessive standards of beauty.

It’s almost no wonder that in this world, Fiona would be desperate to become someone who wasn’t ostracized, or excluded. Fiona’s sole reason for getting married is that she wants to fit into society.

Fiona’s been raised on traditional fairytales, on handsome princes rescuing fair maidens from curses. Her parents stuck her in a tower for almost all of her life, keeping her from realizing that, just maybe, being an ogre isn’t the worst thing in the world. Fiona’s strong and capable, but she’s also been extremely sheltered. She’s constantly been taught that being anything other than the princess in the traditional fairytales is wrong, and she’s never seen examples to prove otherwise.

That’s why when Shrek walks into her life, she starts to come out of her shell. Here is someone different from society, someone like her, and he’s kind and warm (to her, at least). He’s not even lacking in companionship–he’s got Donkey for a friend. With Shrek, Fiona slowly begins to realize that it’s okay to be an ogre.

|

| Princess Fiona and Shrek |

Still, Fiona’s self-loathing over her ogre self goes extremely deep. When she confesses that she’s an ogre to Donkey, she says that no one would want to marry a beast like her. Shrek overhears this, and believes she’s talking about him. When he confronts her about it, and throws her words back in her face, she immediately assumes he’s talking about her. Fiona has overheard Shrek make comments about his identity as an ogre and the issues that come with it, so it wouldn’t be a huge leap for her to consider the possibility that Shrek overheard her and thought she was talking about him. But Fiona’s self loathing runs so deep that she doesn’t even consider the possibility.

Ironically, Fiona doesn’t even seem to focus on the fact that if Shrek is rejecting her, he’s also rejecting himself. After all, he’s an ogre just like her. But, again, she loathes herself so much that she doesn’t even think of that.

Fiona’s marriage to Farquaad is, even from the beginning, one of desperation, not love. She wants to love him because she wants to believe that his kiss will break her spell. When she later realizes that he’s a jerk, she still goes along with the marriage because she wants to have the curse removed. It’s been so ground into her that being different is horrible, that she believes, even though she doesn’t love Farquaad, the kiss of someone “normal” will make her better.

In the short amount of time that we see Fiona engaged to Farquaad, we see that she loses a lot of the character traits that she shows throughout the movie. She reverts back to the eloquent talk that she had in the beginning; she passively sits around waiting for the wedding to start; and she doesn’t speak up for herself, even though she’s clearly miserable. By reverting to the expectations society has for her, she’s “normal” but unhappy.

That’s why the climax of the story, where Fiona reveals that she’s an ogre, is so powerful. By revealing herself to Shrek as an ogre she’s saying that she can’t let him love her, if he can’t love all of her.

|

| Shrek and Princess Fiona |

It’s symbolic that Fiona’s ogre self, the self that has been rejected by society, is Love’s True Form. It doesn’t match up to society’s standards (which makes sense, because society’s standards told her to marry the heartless Farquaad), but it’s the best version of Fiona.

Fiona’s rejection of Farquaad’s marriage proposal is a rejection of the conventional life she’s been taught to want. When Fiona accepts Shrek’s love, she also accepts herself. By Fiona embracing Love’s True Form, she embraces the life that she secretly wants–a life as the best, truest version of herself, no longer in hiding.

Megan Wright is a TV reviewer and co-editor for Watch It Rae! She can be found glued to her computer blogging about her favorite TV shows, movies and books.

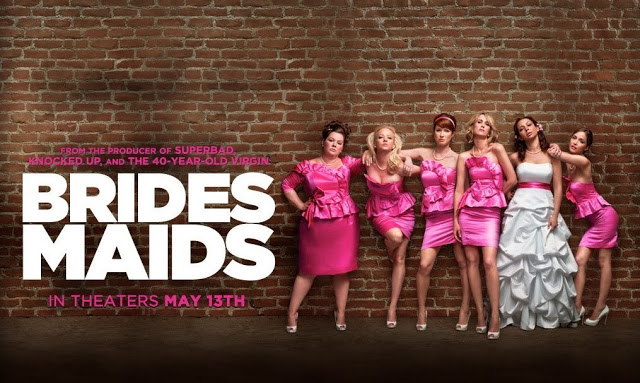

Wedding Week: Why We All Need to See ‘Bridesmaids’

|

| Movie poster for Bridesmaids |

|

| Maya Rudolph and Kristen Wiig exercising in Bridesmaids |

| Drinks, pre-food poisoning, in Bridesmaids |

|

| Bridesmaids karaoke |

|

| Kristen Wiig in Bridesmaids |

|

| The ladies of Bridesmaids |

|

| A sweaty Kristen Wiig in Bridesmaids |

8. They also talk like real-life women. Like the rest of us, they talk about everything in life … they talk about their jobs, their life choices, their regrets, their bodies, their friendships, other women, their hopes and dreams, and, yes, their clothes and even sometimes men. But they don’t ONLY talk about men, which is crucial.

|

| Kristen Wiig’s airplane freakout in Bridesmaids |

|

| Annie Mumolo and Kristen Wiig in Bridesmaids |

So what are you waiting for?

Wedding Week: ‘Bride Wars’: When Weddings Drive a Bitch Crazy

In Gary Winick’s 2009 film Bride Wars, two best friends pit themselves against each other in order to both have their dream wedding day. If this thoroughly unfeminist – not to mention unlikely – premise doesn’t put you off then pull on your spanx, pin up your hair, and settle in to enjoy some fun so light and frothy it may as well be a specially designed valium-laced cupcake.

It pains me to state that a rare successful Hollywood film featuring a rare two female leads (Kate Hudson and Anne Hathaway) orientates itself around the wedding industry, an industry that feeds on female insecurity, causing otherwise sane and sensible women to spend a fortune on a single day in a quest for a level of perfection that probably only exists on cinema screens.

|

| Best friends turned worst enemies |

It also pains me to admit that the film is a firm favourite of mine because the lunacy that is fused to its girliness means it fits very well into that hallowed space known as “comfort movie.” Feel free to judge. I know you have one too.

Written by the female comedy duo Casey Wilson and June Diane Raphael, Bride Wars can be read as a much lighter companion piece to Kristen Wiig’s infinitely dirtier Bridesmaids, were Wiig’s depiction of how women behave when their closest friendship is self-immolating not far more realistic (yes, I do include the part where she hallucinates on the plane) and – let’s be real – funnier.

Bride Wars depicts both its brides – friends since childhood – as beautiful, successful in their careers and in stable relationships. It also depicts their descent into venomous harpies when it emerges that their wedding planner (a dignified and ice-cool Candace Bushnell) has booked both of their weddings to take place at Manhattan’s Plaza Hotel on the same day.

The Plaza, we understand, has been both of the women’s dream venue since childhood visits with their mothers, who were also BFFs. This may be a side issue but, realistically, how many women’s best childhood friend remains their closest friend into adulthood, particularly when they became friends because of their mothers’ friendship?

Also, how realistic is it that both of these women would remain fixated on the goddamn Plaza from the age of six through twenty-six? Yes, the Palm Court is divine but I maintain that at some point at least one of them – probably Hathaway whose character Emma is a teacher – would have looked round and said, “You know? I don’t think it really is worth the money.”

|

| Liv in Vera Wang |

Bride Wars, then, is a film about madness. Emma and Liv (Hudson) are arguably experiencing a folie a deux bought on by that well-known contagious disease, wedding fever. Since before the Great Depression there have been studies showing that even in times of dire need, people in the West will still spend the equivalent of a down payment on a home on their weddings. Tell me that’s not crazy.

Bride Wars is a film that aims to capture its audience, which I think we can take for granted is made up entirely of women, by highlighting the worst side of what Hollywood likes to depict as the nature of women. Rather than solving their planner’s error in a dignified, or even organized way, the brides turn on each other, exploiting each other’s vulnerabilities and weaknesses in ways that only a former ally ever can.

And though it’s amusing to watch the pair go at each other in increasingly underhanded ways – a dye job gone brutally wrong, a fake tan turned neon, deliveries of cakes and sweets causing one bride to gain so much weight that she can no longer fit into her bridal gown, a Bachelorette crashed and dance-off performed – there is also the fact that these acts have consequences so far-reaching that it’s hard to imagine the pair hugging out at the end of the film (which, of course, they do).

Liv’s dress, for example, was by Vera Wang, meaning it probably cost in the region of $25,000. That’s a lot of money to make a former friend waste. The bad dye job turned her locks blue, causing a disastrous day at work that very nearly costs her the job that’s paying for that fancy frock and, one suspects, her wedding as her fiancé is shown to earn less money than her.

But worse than all of this is the fact that, while the women go at each other like thirteen-year-olds with enough money to act out their most schadenfreude-filled fantasies, the men in it are doing nothing. Not strictly nothing. Both the grooms have jobs and seem like OK dudes, but neither of them is running around the city in a vengeful huff because his soon-to-be-wife’s former-bestie is trying to best their wedding day and destroy his woman’s life.

|

| The madness at work |

No, in Bride Wars that brand of madness is entirely female. This says nothing good or particularly realistic about the state of mind of the modern adult female. I mean, yes, we get hurt and pissed off when our friends do something that seems designed to cause pain to us, but how many of us who are not mentally ill follow them around, actively trying to ruin one of the most significant and expensive days of their lives?

For one thing, who would have time, especially if they were trying to plan the happiest day of their own lives at the same time?

So, once again, even though I doubt the writers were trying to make a serious point about how the pressure and expectations of the wedding industry can direly affect women’s mental states, I think the film is about mental illness. You decide.

Alisande Fitzsimons is a writer and stylist from Dublin. She can be found tweeting about weddings and clothes @AlisandeF.