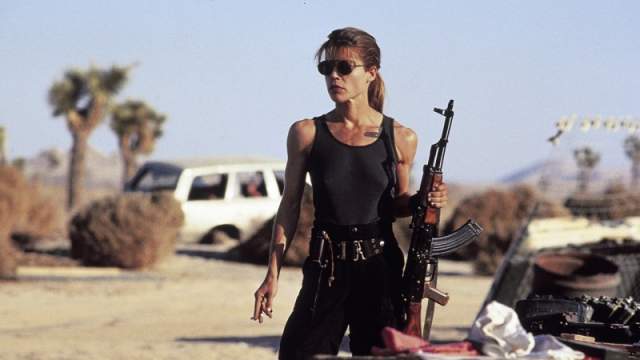

If men didn’t rape, Louise wouldn’t have shot the rapist. If the system didn’t blame rape victims, they wouldn’t have gone on the run. If men didn’t rape, they could have driven through Texas. If the system didn’t blame rape victims, Louise wouldn’t have been so afraid. If women weren’t taught they deserve to be treated like shit, they wouldn’t have had to become fugitives in order to feel free. If there was a place for liberated, powerful women who live on their own terms in this world, they wouldn’t have had to create their own. If there was a place for liberated, powerful women who live on their own terms in this world, they wouldn’t have had to plummet into the Grand Canyon in order to feel free.

I hate that the message — “What you thought you wanted is something you really had all along!” – is applied differently to Dorothy than it is to her friends. The Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Lion are told that they always had a brain, a heart, and courage, and the Wizard giving them their “gifts” is affirmation of their strengths. Dorothy, on the other hand, gets a lecture from Glinda and has to realize that “if I ever look for my heart’s desire again, I won’t look any further than my own backyard.” Her friends get to realize that they were always smart, emotional, and brave, while she has to learn a lesson about being grateful for what she already has.

From the moment our Sex and the City stars have decided to take this trip together, however, Abu Dhabi is viewed through a lens of Orientalism, demonstrating a Western patronization of the Middle East. Starting on the first day in the city, Abu Dhabi is framed derisively as the polar opposite of sexy and modern New York City. It’s also stereotypically portrayed as the world of Disney’s Jasmine and Aladdin, magic carpets, camels, and desert dunes—”but with cocktails,” Carrie adds. This borderline racist trope plays out vividly through the women’s vacation attire of patterned head wraps, flowing skirts, and breezy cropped pants. Take for example their over-the-top fashion statement as they explore the desert on camelback, only after they have dramatically walked across the sand directly toward the camera of course.

The movie makes interesting commentaries on gender. When Liz eats dinner with Felipe, he tells her how he stayed at home with his kids while his wife worked. Liz calls him “a good feminist husband.” In Italy, there’s a great scene where Liz and her friends celebrate an American Thanksgiving dinner to say goodbye. Her Italian tutor’s mother asks if she’s married. When she replies no, the mother declares that she doesn’t understand why a woman would go off and travel by herself. Her friend Sophie comes to her defense saying that no one would say that to her if she were a man and calls her brave for traveling alone. Another woman at the dinner comments on the difficulty of women’s choices.

I don’t think that Spring Breakers, despite its perpetually-bikini-clad bodies, is an addition to the list of ways these young female bodies have been exploited. Instead, Spring Breakers turns that sexualizing gaze back onto the audience members who may have been enticed to see the film based on the promise of nubile bodies. The opening scene — a montage of spring breakers partying hard set to dubstep — is full of drunk white kids, many of the girls flashing their breasts in true Girls Gone Wild fashion. On a small scale, this may have been titillating, but Korine returns to the theme of careless youth partying with a regularity and focus that not only de-sensitizes the flash of nudity, but eventually makes us grimace. This is a generation partaking in activities they’ll regret because they are bored and aimless. The nudity and partying have no meaning, no purpose, because life for these co-eds has no meaning, no purpose. Korine notes that the film “is more music-based than cinema-based. Music now is mostly loop and sample-based … ” — not even the music of this generation is original. We rely on copies of copies for entertainment. Nothing is real. And when nothing is real, nothing matters.

So what makes a man’s coming-of-age story a “feminist” travel film? The fact equal-opportunity is still so rare these days? No, (though on a side note: sadness and anger!). It’s because as Mercer’s trip progresses, the catalysts are fully-realized women who exist for more than just his gratification. His trip is prompted by his mother’s death. All his stops along the way involve women who reveal something about themselves and/or Mercer. Finally, Kate, from whom Mercer stole the car, tracks him down and finishes the road trip with him. In a moment near the end, Mercer asks Kate, “Want to go to Louisiana with me?” and she raises her eyebrows and notes, “It’s my car,” as if to sum up that though Mercer has been making his own way, it’s women who are enabling and teaching him. It’s women he has learned to be like or not-like, from his mom to his first crush to this girl he just met over the phone.

What all these movies have in common is that they take women who are having personal, relatable conflicts and show that a good adventure and a strange city can revive one’s outlook on life.

While it might not be difficult to find a good female action movie, or even a solidly entertaining “girl time flick,” these movies are unique in their pensive and thoughtful approach to the difficulties women face in life. They show that a little adventure and new surroundings can create a whole new perspective.

They’re certainly worth the watch.

The themes of socially defined and limiting masculinity throughout Easy Rider go hand in hand with the theme of an elusive America. In fact, the idea that this idyllic America can be found is as entrenched in our mythology as the idea that gender performance is set and rigid. Both are myths that are central to our being as a society, and both are myths that are incredibly destructive.

To her credit—and displaying the role she plays in the protection of her daughter—Sheryl looks at Olive and says, “I just want you to understand that it’s okay to be skinny and it’s okay to be fat, if that’s what you wanna be. Whatever you want, it’s okay.” While Olive is processing this, Richard asks Olive to consider whether beauty queens are “skinny or fat,” to which she quietly replies “They’re skinny, I guess.” And Sheryl shoots Richard a death-ray stare as the waitress comes over and serves Olive her “a la mode-ee” side dish.

The director’s feminist aesthetics are apparent in the framing of these early flashbacks. As Mona emerges from the sea, the viewer sees that she is being watched by two young men. Varda’s shot of the naked Mona is succeeded by a shot of postcards of naked women for sale in a bar frequented by the same young men. Disturbingly, they talk of missed opportunities. Varda depicts the sexual objectification and exploitation of Mona in a quite unobtrusive, subtle fashion. Many of the male characters reveal their misogyny themselves in interviews. A garage owner who exploits Mona has the audacity to say female drifters are “always after men.”

Focusing on the existential angst of two white Americans in Japan without any well-defined Japanese characters is enough to turn off many race-conscious viewers to begin with, and Lost in Translation doubles down with some cringeworthy Japanese stereotypes. The film gets alarming mileage out of its Japanese characters pronouncing l’s and r’s similarly, which feels even more dated than the also strangely boundless fax-machine humor in this 2003 film. Charlotte at one point asks Bob why “they mix up l’s and r’s” and he suggests it is “for yuks,” but it isn’t actually funny.

In this essay, we ask how the genre of comedic travel-movies encodes gender-topics and how these are linked to the metaphor of a journey. Thereto we loosely compare the eponymic female protagonists of Woody Allen’s comedy Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2008) and the dandy-male protagonists of the comedy The Darjeeling Limited (2007) directed by Wes Anderson. Both movies follow socially close connected White, heterosexual US-Americans, who go on a trip to another continent, where they are afflicted by emotional disputes. We also ask how the particular female or male main ensemble is constructed in dialogue to the projected otherness of the countries they are visiting.

Yes. It is always a joyful occasion to see African American romances onscreen (it’s incredibly rare to feature an all African American cast in this genre–unless it’s Tyler Perry related grrrrr!) and not have courtships be the overplayed “thin line between love and hate” stereotype, but Stella’s relationship with Winston wasn’t exactly great as it progressed to turbulent fights and public screaming matches.

By the film’s cheesy end, I only wished for Delilah’s ghost to visit Stella and continue their friendship in a spiritual manner as Stella embarked on her personal quest. Perhaps even treating herself to more splendid travels and finding other pursuits called “fun” that don’t involve young men.

I could easily and happily blame Richard Linklater for making me believe in destiny, fate, kismet, or the idea of a soul mate. When Before Sunrise was released, I was twelve or thirteen. I remember getting it from the video store with my best friend when we had one of our regular sleepovers. I sat there, greasy-and-brace-faced, completely swindled by the words that tumbled out of Ethan Hawke’s crooked mouth. I wondered if any of the boys whose names I drew on my notebooks or the sides of my Converse One-Stars would ever feel the way about me that Ethan Hawke felt about Julie Delpy.

I think it’s necessary to detach from our obligations and get lost for a while, even if it hurts the ones we love. As human beings (let alone professional creatives), we forget that inspiration is the key element to everything that we do. In all honestly, forcing creativity is the crux of the problem. I recently picked up a book called Daily Rituals: How Artists Work to try to see how my heroes did it. The ultimate conclusion? Practice makes perfect, but you can’t rush it. Although Sylvia ditches her friends for a random stranger, she is choosing to embark on a journey of self-discovery, even if she did so unconsciously. And she has to hope that her friends can understand and love her all the same.

Hypocrisy is a common theme in this film, particularly in Mark’s case. I have found it difficult to sympathize with him, as he’s foul-tempered, selfish, irrational, a workaholic, overly ambitious, and, worst of all, ignores his wife and daughter. He claims he hates the idea of marriage and yet impulsively marries Joanna. He says he’ll never ignore a hitchhiker as long as he lives, and 10 years later, he breaks that promise. He has a one-night-stand while on a business trip alone, but writes a letter to Joanna full of lies about how much he misses her. Once he becomes successful, he claims that he has given Joanna everything that she ever wanted, but in truth, has just given to her everything that he wants. (He reminds me a bit of Homer Simpson gifting Marge a bowling ball with his name on it.)