This guest post by Rowan Ellis appears as part of our theme week on The Female Gaze.

The Female Gaze, and scathing criticism of it, has come bursting into the world recently through Channing Tatum’s pecs. And not in an Aliens face-hugger way either (Magic Mike III anyone? No?). Magic Mike and its extra extra large sequel have been talked about as both a rare movie celebrating female sexuality, and as a prime example of feminist double standards. How can you complain about objectifying women’s bodies and then not criticise a film which seems to do the same to men? The whole debate was fascinating to me as a insider-outsider; sure I’m female, but I’m also a lesbian and so have very little interest in any part of Channing Tatum apart from his underrated comedic timing. I’ve talked before about the strange awkwardness of watching both Magic Mike films as a queer woman in the cinema (what are you doing with that spinning metal wheel of sparking fire, Mike? Do you want to burn your dick off? etc), so when this month’s Bitch Flicks theme was revealed to be the Female Gaze, I was ready and raring to go. But it turns out that the Female Gaze, and particularly the Queer Female Gaze, was a lot harder to pick through than I thought.

But let’s start at the beginning. Although the Male Gaze was a term coined in the 1970s, it was just a concrete name for an age old phenomenon. The Male Gaze is two-fold:

- The sexual objectification of passive female characters.

- More generally the tendency to default to male protagonists, points of view, and stories.

The Gaze can be seen literally as a gaze, the way the camera interacts with the women it looks on, doing things like introducing female characters by trailing slowly up their bodies rather than establishing them with their face and actions. This differing treatment of men and women can be seen to be both informed by a patriarchal social structure, but also to reinforce it. Women can be on screen in a sexual situation, and not be subject to the Male Gaze, provided it is plot-relevant and that they are not only there to be a one-dimensional character purely put there for men’s pleasure. Alice Eve’s controversial underwear scene in Star Trek Into Darkness would be a perfect example of how, although she was not a one-dimensional character in the film as a whole, she was given a pointlessly objectifying scene which established nothing about her character, and seemed oddly out of place. The scene was also an example of how the sexualisation of women on screen, as opposed to men, is often used to reduce their power or respect in some way, either by playing into the “whore as worthless” idea, or by making them physically vulnerable as happened with Carol in the film.

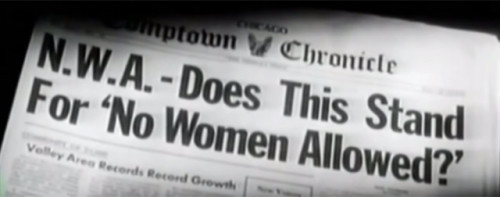

The Female Gaze, however, is a trickier subject, partly because its a newer phenomenon–as Transparent‘s Jill Soloway said last year, “We’re essentially inventing the female gaze right now.” Both women’s stories and their sexuality are much less likely to be the focus of screen time historically. Definitions, classic camera angles, a checklist of what the Female Gaze might be, are hard to find when only 29 percent of current movies have female protagonists, and all women creative teams are rarer than panda sex. Is The Female Gaze always found in films made by women, for women, or about women? And does that gaze have the same definition as the Male Gaze with the genders switched? Perhaps not. Is it really true that women don’t objectify men? That they always view them as complete and whole human beings? The popularity of the Chippendales suggests otherwise. And our old friend Magic Mike is surely the obvious example of that female sexuality in action, proving women’s sexual desires make them see men as objects just as much as men do to women in films.

However, when we look at the story of Magic Mike and his magic mic, the fact the main characters are strippers means the lack of clothes is plot dependant, and the films revolve around an exploration of the men’s interests, personalities, desires, and dreams. They are sexual, but they are also three-dimensional characters. Moreover, romantic comedies are always an example cited by critics of feminist film theory of movies which reduce men to merely a female fantasy. If that’s the truth, then women’s fantasies of men are a lot more full, positive, and respectful than men’s are of women. Men in romantic comedies aren’t just one-sided sexual beings; the appeal of them is hinged on their personal compatibility and often flawed realness as well. Hugh Grant made a career out of playing the soft-eyed Englishman, who bumbled along and stuttered over his words, hardly a paragon of sexual virility you might expect from the directly switched Male Gaze. Conversely, if women’s sexual pleasure and desire is depicted on screen, it is seen as much less acceptable than a man’s, particularly telling in the differences of age rating given to films that show male vs. female orgasms and oral sex.

If the Female Gaze is hard to pin down, then Queer Female Gaze is near impossible. What I mean specifically with that term is the Gaze we might be able to see in work produced for and about women who are attracted to women. Queer female characters in films made for and by end are almost always either packaged in the same sexually objectified way as straight women, or they are the butt of jokes as “ugly butch lesbians.” So although ostensibly it could be assumed the Queer Female Gaze would be identical or at least hugely similar to its male counterpart, in fact it cannot be mapped directly onto the Male Gaze for a few crucial reasons:

- The number of films made for, by and about queer women in mainstream cinema is embarrassingly small, and is not compatible to that male default I mentioned earlier.

- The sexual desires of queer women are different to that of straight men.

- The male ownership of female bodies is something tied to male behaviour rather than an intrinsic reaction to female bodies by anyone who desires them.

- Queer women are interested to see interesting women on film, meaning having women be solely sexual objects is not necessarily going to fly with us.

So maybe it’s something in-between, or something new entirely. Maybe, as I have come to believe over the last few weeks, it isn’t something which has a real definition or direction, simply because it doesn’t have a present or strong enough canonical tradition in media. Instead I’ve tried to look at current examples of media for and containing queer women, to see where it differs or intersects with the Male/Female Gazes.

As a queer woman it might seem to any men who are attracted to women, that I would love images of half naked oiled up women, because they do. But while they may just see the object of their desire, I have to also see myself. So when I see sexualised women on screen who are given no agency, plot or power, I don’t get anything positive from that. It feels unbelievably naive and worrying that someone who is for all intents and purposes a pliant sexual object could be genuinely and maturely desirable. This is the source of a long held observation in the queer world that “lesbian porn” is so obviously and inexplicable made for straight men. It also may be why I have never been able to come out to a male stranger who is trying to chat me up without him immediately asking for a threesome. I am infinitely more interested in women who are allowed to make decisions, tell their stories, control the narrative, in addition to being autonomous sexual beings, because that’s how I see myself, my friends, my partners.

Secondary issues that comes with the Male Gaze are problems like a lack of movies that show meaningful female friendship (as shown most simply through a quick look at how many films don’t pass the Bechdel Test; although films that pass don’t necessarily show female friendship, it’s pretty hard to find a film that fails the test that does). Shows with a focus on queer women, like Orange is the New Black or the web series Carmilla, also have a strong emphasis on female friendship alongside female sexual or romantic relationships. The desire to show a complex version of yourself seen with male characters in the Male Gaze, alongside a desire for a complex version of your partner seen with male recipients of desire in the Female Gaze, combines in the Queer Female Gaze to produce sexual and romantic relationships often rooted in friendship.

This is furthered by the prevalence of narratives in queer cinema about coming out and finding community, which can give a tentative and holistic treatment to attraction. In the quintessential lesbian teen movie But, I’m a Cheerleader, Graham and Megan begin as friends and develop parallel to Megan’s own acceptance of her sexuality. Their relationship is more than just sex, because it is so tied to her understanding of herself, in a way which values Graham far more than the Manic Pixie Dream Girls of the “young straight man finding himself through romance” narratives of the Male Gaze. The showing of intimate, dirty, casual or loving sex in any queer narrative does not remove the possibility of the women participating in this sex being fully imagined characters. The Gaze means female desire, both sexually and the desire to see herself present and whole on screen, and this is even more effective the more women you present for those queer female audience members to align themselves with.

Women can be seen on screen as sexual beings, without being sexual objects. Queer women’s position as both gazer and gazee give a brilliant opportunity to reject the tired reduction of female characters in and out of the fictional sheets. What remains to be see, as we make the slow journey towards mainstream queer media, is whether the defaults of The Male Gaze, with its dehumanising camera shots and need for a male presence on screen, will bleed into the Queer Female Gaze through what we take for granted as “just how cinema is made.”

Rowan Ellis is a British geek using her YouTube videos to critique films, TV, and books from a queer and feminist lens.