|

| Urban Fantasy is here to stay |

|

| Lettie Mae in True Blood |

The radical notion that women like good movies

|

| Urban Fantasy is here to stay |

|

| Lettie Mae in True Blood |

|

| Laura (Mary Tyler Moore), Richie (Larry Matthews), and Rob (Dick Van Dyke) in The Dick Van Dyke Show |

This is a guest post from Caitlin Moran

Laura and Rob Petrie had one child together, a son named Richie. Because Richie is in elementary school for the whole of the show, Laura’s role as a mother focuses on the challenges of raising a small child. She worries that he might be sick when he refuses a cupcake, and helps Rob explain why Richie’s middle name is Rosebud. (It’s an acronym for the names that their parents and grandparents suggested for the baby. Unsurprisingly, that was Rob’s idea.) In the episode “Girls Will Be Boys,” Richie comes home from school three days in a row with bruises on his face, and admits that a girl has been beating him up. After Rob’s visit to the suspected lady bully’s father turns up empty, Laura goes to the child’s house to get to the bottom of the strange beatings. After the girl’s mother insults and dismisses her, Laura refuses to leave until she’s said her piece. “You may not be the rudest person I’ve ever met,” she declares with her trademark quiver, “but you are certainly in the top two.” Door slam, and our girl storms off with the moral high ground and not a hair out of place in her perfect coif.

|

| Laura pouring Richie a glass of milk |

That doesn’t mean that The Dick Van Dyke Show’s treatment of Laura Petrie is without its problems. It is more or less assumed throughout the show that she is a mother and a housewife above everything else, leaving her former aspirations of a dancing career behind. In season three’s “My Part-Time Wife,” Rob is woefully unable to handle Laura stepping in as a secretary at his office, even though she performs her tasks at work deftly and still keeps up the house and supports Richie. When Rob throws a grown-man tantrum over her abilities, Laura apologizes and concedes that she has been “flaunting her successes.” Everyone groan on the count of three.

|

| The Great Lie (1941) |

|

| Bette Davis stars in The Great Lie |

|

| Mary Astor plays Sandra |

|

| Maggie and Pete post-wedding |

|

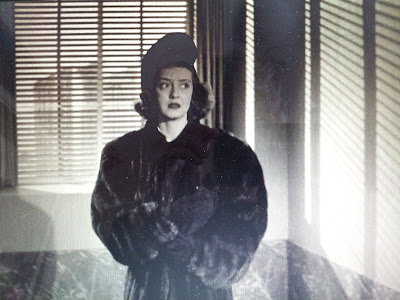

| Maggie arrives at Sandra’s apartment in suddenly-noir lighting |

|

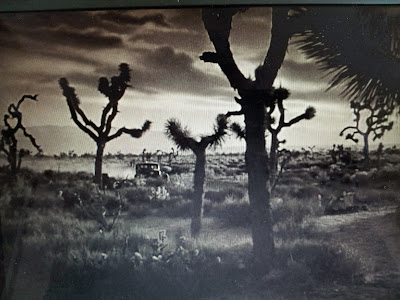

| Their car arriving at the Arizona safe house |

|

| Maggie relents and cuts a slice of ham for Sandra |

|

| Maggie alone on the deck, awaiting the birth of the baby |

|

| Sandra playing Chopin, dressed to impress |

|

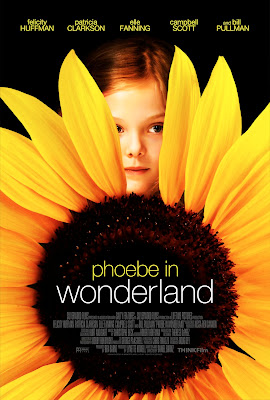

| Movie poster for Phoebe in Wonderland |

imdb plot summary: The movie focuses on an exceptional young girl whose troubling retreat into fantasy draws the concern of both her dejected mother and her unusually perceptive drama teacher. Phoebe is a talented young student who longs to take part in the school production of Alice in Wonderland, but whose bizarre behavior sets her well apart from her carefree classmates.

Well, on the surface, the movie is about Phoebe and her struggle to fit in with her peers. But it quickly turns into an examination of motherhood and parenting in general, when Phoebe’s odd behavior gradually worsens: she spits at classmates, she obsessively repeats words and curses involuntarily, she washes her hands to the point that they bleed—and she explains to her parents over and over again that she can’t help it. However, her mother (and father), being academic writer-types (Hillary is actually attempting to finish her dissertation on Alice in Wonderland), merely choose to see their daughter as nothing more than eccentric and imaginative.

The caretaker r ole falls exclusively to Hillary. She’s a stay-at-home mom trying to write a book while also attempting to care for two young daughters. While her struggle to play The Good Mom definitely lends sympathy to her character—I mean, honestly, what the hell is a good mom?—I couldn’t help but despise her selfishness and blatant disregard for Phoebe’s needs. Even though both parents decide to (finally) get Phoebe into therapy, it’s Hillary who refuses to accept the doctor’s diagnosis, even going so far as to remove Phoebe from therapy, deliberately hiding the diagnosis from her husband.

ole falls exclusively to Hillary. She’s a stay-at-home mom trying to write a book while also attempting to care for two young daughters. While her struggle to play The Good Mom definitely lends sympathy to her character—I mean, honestly, what the hell is a good mom?—I couldn’t help but despise her selfishness and blatant disregard for Phoebe’s needs. Even though both parents decide to (finally) get Phoebe into therapy, it’s Hillary who refuses to accept the doctor’s diagnosis, even going so far as to remove Phoebe from therapy, deliberately hiding the diagnosis from her husband.

The problem here, and where the movie most succeeds, is that Hillary feels alone as a parent. She believes that her children’s struggles will ultimately reflect poorly on her as The Good Mom, and she even says at one point that she doesn’t want her daughter to be “less than.” Obviously, we live in a society that mandates the over-the-top importance of living up to an unattainable standard of proper mothering (see: any celebrity mother and the scrutiny she faces, with barely a mention of celebrity fathers), and Hillary definitely effectively represents that unattainable standard.

successfully portrays the societal trend of the working father: he pokes his head in when necessary, checking in on his daughters, and demonstrating just the right balance between quirky annoyance at their neediness and curiosity about their daily lives—he shows up to parent/teacher conferences, he consoles Phoebe when she gets in trouble at school, and he genuinely wants to participate; he’s just not required to maintain the role of The Good Dad—it doesn’t exist.

successfully portrays the societal trend of the working father: he pokes his head in when necessary, checking in on his daughters, and demonstrating just the right balance between quirky annoyance at their neediness and curiosity about their daily lives—he shows up to parent/teacher conferences, he consoles Phoebe when she gets in trouble at school, and he genuinely wants to participate; he’s just not required to maintain the role of The Good Dad—it doesn’t exist.One of the aspects that struck me in the show though, is the portrayal of motherhood. Far from being absent or swept to the side, the film’s mothers are a driving force in the plot development and are some of the most multi-dimensional of the series (credit has to be given to the actresses who play them).

|

| Game of Thrones |

|

| Maggie Gyllenhall in Sherrybaby |

|

| Maggie Gyllenhaal in Sherrybaby |

|

| Director Laurie Collyer with Maggie Gyllenhaal |

|

| Director of Sherrybaby, Laurie Collyer |

|

| Piper Laurie and Sissy Spacek (1976 film) |

This piece is from Monthly Contributor Carrie Nelson.

|

| Marin Mazzie and Molly Ranson (2012 musical revival) |

|

| Patricia Clarkson (2002 made-for-TV movie) |

Carrie Nelson is a Bitch Flicks monthly contributor. She was a Staff Writer for Gender Across Borders, an international feminist community and blog that she co-founded in 2009. She works as a grant writer for an LGBT nonprofit, and she is currently pursuing an MA in Media Studies at The New School.

| Rosemary (Mia Farrow) |

|

| Lorelai Gilmore (Lauren Graham) |

|

| Rory Gilmore (Alexis Bledel) |

|

| Movie night with the Gilmore Girls |

|

| Emily Gilmore (Kelly Bishop) |

|

| Three generations of Gilmore Girls |

|

| Jamie Lynne Grumet on Time |

“I should’ve killed myself when he put it in me…. I should’ve given you to God when you were born, but I was weak and backsliding, and now the devil has come home.”

|

| A crucified Mrs. White |

|

| Sissy Spacek and Piper Laurie in Carrie |

“All the kids think I’m funny, and I don’t wanna be. I wanna be normal…. a whole person, before it’s too late for me to –“ [Margaret throws tea on her face, Carrie wipes it off].

|

| Piper Laurie as Margaret White |

This is a guest review by Leigh Kolb.

Motherhood is firmly rooted in the feminine sphere—inside the womb to inside the nursery. In the critically acclaimed television drama Sons of Anarchy, the gendered spheres are clear and present. Sons of Anarchy is oftentimes dubbed “Hamlet on motorcycles” since the plot line bears a strong resemblance to Shakespeare’s Hamlet (which is an important note for feminist analysis, considering Shakespeare’s own subversive feminism). As in Hamlet, Sons of Anarchy’s audiences and critics often focus on the protagonist, the “ghost” of his father, his nefarious stepfather, and the men who surround him. The excitement of politics, public tension, violence, and man’s inner struggle always trumps the inner-workings of the home and child-rearing. The power is in the public sphere.

|

| Gemma threatens Wendy. She makes it clear that no one will hurt her son or grandson. |

The Mothers of Anarchy, on the surface, have no control. In reality, they have all of the control.

The matriarch “old lady” (the endearing term club members give to their partners) of the California motorcycle club is Gemma (Katey Sagal). She is the Gertrude-inspired character who has married one of the original members of the club, after her husband was killed. Her first husband helped found the Sons of Anarchy motorcycle club after Gemma became pregnant with their son and wanted to settle in Charming, where her parents were from. She may not ride, but her instincts and desires steered the club from its inception. The town’s police chief refers to Gemma as “leaving Charming when she was sixteen and showing up 10 years later with a baby and a biker gang.”

|

| Tara and Gemma together saved baby Abel’s life, and Jax, his father, holds him. |

Gemma’s son Jax (Charlie Hunnam) has a pregnant ex-wife, Wendy (Drea de Matteo). As Gemma is driving to check on her, Wendy is in the kitchen injecting herself with a syringe-full of meth. The camera pans out to a very pregnant Wendy with her hand on her belly, relaxed. This is a fallen mother. Gemma finds her in a pool of blood, curses at her, and rushes her to the hospital. At the hospital, Tara (Maggie Siff), a surgeon and Jax’s ex-girlfriend, is tending to Wendy and Abel, who was delivered via emergency c-section ten weeks premature. Immediately the audience is presented with the powerful mother and matriarch, the bad mother (and few things are worse in our society than a bad mother), and the professional mother, who is responsible for keeping Abel alive since his biological mother could not.

|

| Gemma’s maternal instincts are fierce and stinging. |

Toward the end of the episode, the men of Sons of Anarchy are engaged in club warfare, and commit brutally violent crimes (involving guns, explosives, and vehicles) as they navigate the changing waters of their club’s purpose and see their territory shifting to guns and drugs.

|

|

Tara and Jax have a son, Thomas, and they together raise him and Abel.

|

The masculine sphere is powerful, aggressive, and largely superficial. The feminine sphere, while perceived as less important and less powerful, deals in matters much closer: giving life, manipulating life, and sustaining life. When Jax comes to the hospital to visit his son, he is beat up and bloodied from his duties outside. Tara tells him to clean himself up, and then he can see his son. Tara—who gave Abel his heartbeat, not Wendy—is in control. It’s simply a matter of time before she and Jax are in a relationship and she is clearly an old lady in training.

|

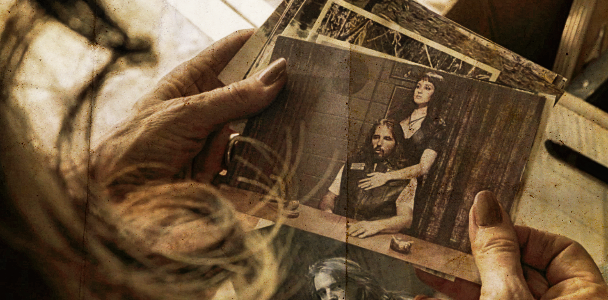

| Gemma looks at an old photo of her and John, Jax’s father and the co-founder of SAMCRO. |

Possibly the most obvious mother archetype in Western culture is the Virgin Mary. Sons of Anarchy does a commendable job of avoiding the virgin-whore dichotomy so prevalent in matters of femininity and motherhood. Gemma is a sexual creature and desires sex (one episode even deals with her battling vaginal dryness after menopause), but that isn’t problematic. The show manages to avoid the all-too-often inferred Oedipal nature of Hamlet and Gertrude in the Shakespeare original, showing that a woman can be sexual, and be a mother, and that’s OK.

In an excellent piece at Yes Means Yes, a feminist blogger notes that “The strong women characters are not terminators with breasts, they’re real humans with full inner lives and complicated problems. The plots often explore women’s lives in ways that mainstream shows overlook. And the show humanizes women, like sex workers, who are too often presented as one dimensional.” Indeed, even the porn stars are human in Sons of Anarchy—not just human, but capable of mothering, and mothering well.

SAMCRO becomes affiliated with a porn production company, and club member Opie’s girlfriend (and eventual second wife) is one of its stars. Lyla has a son, and is compassionate in her role as step-mother to Opie’s children. Lyla is a caring mother, and also serves as a catalyst for conversations surrounding the topics of abortion and birth control. For motherhood shouldn’t just be about mothering children, but also about making choices about what’s best for the entire family (which sometimes means not having more children).

In season three, Lyla becomes pregnant and does not want to be (her relationship with Opie is not solid, and pregnancy would end her career in the porn industry, and she wants to work a few more years). Tara offers to take her, and she also is pregnant and decides she wants to schedule an abortion. The entire scene is without judgment or negativity—it’s a clean clinic, and a simple procedure. Tara references having an abortion at six weeks in her previous abusive relationship and that it was “not a baby” at that point. Rarely is abortion presented as realistic in popular culture. Feministing says of the episode, “Most TV shows won’t even present abortion as a viable option and if they do, it’s usually stigmatized and quickly discarded in favor of adoption or keeping the unintended pregnancy.” Later, when Opie discovers Lyla had an abortion and is taking birth control pills even though getting pregnant is her only way “out” of porn, he is angry. But it’s clear that the audience isn’t supposed to be.

Tara ends up not having an abortion, but not because of a moral awakening. She is abducted and almost killed by SAMCRO enemies, and is able to escape by telling the abductors she’s pregnant. After the ordeal, she and Jax see the unharmed baby on an ultrasound, and reconcile. At first, Tara appears to be more submissive after being held captive and choosing to have the baby. As the series progresses, however, viewers see her coming to power in the club by her own choosing. She will mother SAMCRO sons—adopting Abel and giving birth to Thomas—and she will become the matriarch.

|

| Tara is poised to take over Gemma’s position as matriarch. |

As central as motherhood is to the various story arcs of Sons of Anarchy, one can’t help but notice that these strong female characters lack mother figures themselves. While Gemma had a mother growing up, she died from the family’s “fatal flaw” (a genetic heart condition). Tara’s mother died when she was young, and she inherited her father’s house and car. Father-son relationships are central to many of the storylines (certainly the relationship between Jax and his father’s letters, a.k.a. his “ghost,” and his relationship with his stepfather Clay; Opie’s relationship with his father, SAMCRO’s other founder; and Jax’s relationships with his young sons). In fiction, male protagonists are often driven by their relationships with their fathers—away from them or toward reconciliation. However, while audiences continue to see more female protagonists, those characters often have no mothers or are more influenced by their fathers or male mentors (The Killing and Homeland on television, for example, or Twilight and The Hunger Games in text and on film).

Of course this is not a new phenomenon. In Shakespeare’s works, “Fatherhood appears in full gamut, but motherhood, especially in the relationship of mother and daughter, is almost, though by no means quite, absent.” Hamlet’s Ophelia just had a father and brother to guide her (tragically), and no mother. Strong women are often portrayed as being on their own.

These reminders of the gendered spheres—men are in public, in politics, connected to their ancestors and to the world around them while women are inside, working in the home and raising another generation to fulfill these same gendered roles—continually romanticize the role of father and downplay the role of mother. So when modern women emerge on screen, even the most complex and nuanced characters such as those in Sons of Anarchy, there’s still the trouble of True Womanhood, at its core, not being rooted to power in connection. Instead, these women are lone wolves, seeking power where they can and how they can, because their mothers could not or chose not to—or perhaps because it’s simply not a narrative that’s at all woven into our culture.

In an interview, Sagal said of Gemma, ”At the core of her, she is a mother to all of these men. As tough and dark as she is – and she will slit your throat for the right reasons – she is big-hearted.” The undertone of this quote is that Gemma cooks big meals, cleans up, and protects her “men.” Tara also grows into the role, serving as an on-call doctor for the club, bringing men back to life who would have otherwise died or been arrested. They are biological mothers to their sons, and mothers to the Sons. While the spheres are in place, the reality of the series is that these mothers may be perceived as being without power behind closed doors while the boys are killing, being killed, and making business decisions, but the power the mothers yield is monumental. Gemma has orchestrated the club from its beginning, and the fourth season ends with Tara standing over Jax at the head of the SAMCRO table. The audience knows the mothers’ roles, but the men often seem oblivious. The same can be said for Shakespeare’s mothers (it’s widely believed that Gertrude had a part in King Hamlet’s death plot). The audience will have to wait, however, to see if Western culture ever gets it right and removes the spheres that give the perception that motherhood lacks the power and strength of a twin-cam Harley.

|

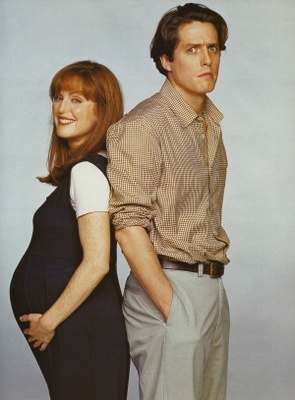

| Julianne Moore and Hugh Grant in the film Nine Months |

This is a guest review by Tyler Adams.

Male Pregnancy

Nine Months, contrary to all expectations, is not about pregnancy. It’s about a man coping with a pregnancy. Yes. Here’s a film whose subject absolutely and biologically requires a woman – and it’s still about a man.

However, Nine Months does achieve sex equality of the most dubious sort – it’s insulting to men and women.

In the world of Nine Months, women have already accepted that their value lies primarily in their fecundity and that raising children is the only thing that matters. And now, it’s time for men to learn the same lesson.

Rebecca, whose unplanned pregnancy kick-starts the plot, knows full well the consequences of pregnancy. And she ignores them. She wants to keep the baby, immediately, after about five minutes of running time where she isn’t even onscreen.

To the film’s credit, it doesn’t demonize Rebecca for subtly, whisperingly alluding to abortion, but the film glosses over it too much to truly be considered ‘pro-choice.’

The conflict in the film’s first act is all about Samuel accusing Rebecca of getting pregnant on the sly. Yes. She tells him she’s pregnant and he turns it into an act of aggression against him. He blames it on her: condescendingly scoffing that birth control could be anything other than foolproof.

Then we get delightful dream sequences wherein Samuel imagines Rebecca as a praying mantis trying to eat him.

As Anita Sarkeesian points out in her excellent video ‘Tropes vs. Women: The Evil Demon Seductress,’ most praying mantis species don’t engage in sexual cannibalism. And neither do women. Except to adolescent men terrified of female sexuality.

Then there’s Samuel’s friend Sean, our childfree Straw-man. His girlfriend says she wants kids, she leaves when he says ‘no’ – a week later, he’s self-admittedly using another woman to ‘get him over the rough spots.’ He describes her breasts, calves, and skin like food, basically making her sound like a golem made of calzones, candy, and cake.

Bobbie, his ‘girlfriend’ is a stereotypically attractive young woman who literally never says a word during the whole film and has no narrative purpose other than temporary eye candy – so the film treats her about as well as Sean does. With Sean, the filmmakers are essentially equating child-freedom with misogyny. Hey, all women want kids, so not wanting to have kids means being anti-woman, right?

There certainly aren’t any major single, childfree, or independent women in the film. Gail is the only other main adult female character, and she has three daughters and one on the way. She talks to Rebecca about how ‘pregnancy is our profound biological right, something men can never experience,’ when Rebecca expresses her one, solitary note of doubt in the film (in a conversation that doesn’t even pass the Bechdel Test, given that it’s all about men and childbirth). This is pretty much the only time the film really deals with Rebecca’s perspective in a way that doesn’t relate to Samuel.

The idea is that it’s a woman’s duty to have children, which is ‘natural’ and therefore good, and a source of female privilege. Gail even frames this in feminist terms, as if Karen Horney’s ‘womb-envy’ concept was a step forward for gender equality (Enlightenment-era chauvinists celebrated women’s fecundity, too – Enlightenment-era feminists spent more time talking about women’s rights), and there’s anything empowering about the idea that women absolutely must have children regardless of their personal feelings, because, apparently, it’s the one advantage they have over men.

Rebecca calls independent single motherhood ‘fashionable,’ and ‘PC,’ basically dismissing it. She says she would rather have a family – as if a single parent family doesn’t count. All Samuel has to do is propose. Why she doesn’t just pop him the question is unexplained. Apparently, even the audience takes it for granted that that’s the man’s decision to make.

Nine Months is trying to celebrate motherhood through the eyes of a reluctant father. Rebecca’s feelings are barely addressed, and Gail doesn’t seem to know how to celebrate motherhood without also demeaning the childfree. She says of Samuel, ‘You have a baby, that means he’s gotta grow up. That’s what he’s afraid of. I mean, the baby’s the fun part…Look at all this stuff.’

She’s referring to the toy store merchandise. Yes. Apparently the joys of motherhood are not bonding with and nurturing other human beings, but buying them things. Gail has the ultimate conservative vision of motherhood – it combines chauvinism and capitalism!

Professional Parents

“What if the baby can see…your penis, coming toward it, that could scare the hell out of a baby…or what if your penis hit it in the head; it could cause brain damage…”

I’m not embellishing. That’s what Rebecca says, five months into her pregnancy, right before she and Samuel have sex. Rebecca is in her thirties, and – well, given the number of biological errors she made in two lines, I’m terrified of what else she doesn’t know about things you should and shouldn’t do during pregnancy.

What does it say about the state of women’s health education that this scene does not read as satire? And if it was supposed to be funny, well – maybe it could work as horror comedy, but I didn’t see any real commentary.

By the way, it should be mentioned that Samuel is a child psychotherapist. Or ‘kiddy shrink’ as Gail calls him. He’s a child psychotherapist and doesn’t know the first thing about pregnancy. He doesn’t know that amniotic fluid in the uterus protects the baby, and the cervix is blocked throughout most of a pregnancy, or you’d think he would have told Rebecca about it during their attempted sex scene.

He’s allegedly successful at his job, but all we see is his being clueless around children, insensitive around women, and ignorant about everything he should be an expert on. The man has to read a book like What to Expect When You’re Expecting, as if he’s never taken any classes on prenatal development. Well, he didn’t know that birth control is only 97 percent effective, so let’s just assume he’s never even taken sexual education at school.

We do see a competent, female gynecologist who more or less helps set Samuel on the right path, but for some reason, we spend a lot more time with bumbling Russian stereotype Dr. Kosevich. All the better to humiliate Rebecca with, I suppose, during her first doctor’s appointment, and later, during the world’s most farcical labor scene where Samuel nearly kills several people trying to get her to the hospital. Oh, and he starts a fistfight during her delivery. How you advocate birth while making it look horrible and playing it for juvenile laughs is anyone’s guess.

Marty and Gail are ultimately the people Rebecca and Samuel turn to for advice. No matter how poorly socialized their daughters are, they’re experts. A child psychotherapist like Samuel has to ask Marty and Gail for help, and as far as the narrative goes, they outrank a gynecologist. Even though Marty believes that you can tell the fetus’s gender by whether the mother’s carrying high or low, and that sexual positions influence sex determination. Although, the anti-intellectualism works well with the film’s overall sneering at creative and professional individuals.

Sean: “…the world is overpopulated; our society has too many starving children.”

Gail: “Well, I would say our society has too many starving artists…this was our parents’ home, but I don’t see you making any contribution…you keep this up you’ll die alone, like a dog, like a bum. Like Van Gogh.”

Sean is an artist, and Gail demeans him for it, because hey, we all know art doesn’t pay. Not like owning a car dealership like Marty, which is a much better contribution to society, of course.

Of course, Sean’s work seems irrelevant. Since he doesn’t ‘have’ a wife and kids, he’s not making any meaningful contribution to the world at all, according to Gail. She equates being single with being isolated, and being childfree with being childish. And the film takes her side.

When Sean argues that she and Marty used to have interests, and are now just obsessed with their children, she doesn’t even deny it. She just affirms that this is the way it should be. After all, earlier Rebecca instantly accepts that she has to quit her job as a dancing instructor – not just take a leave of absence; actually quit. Samuel, after his transformation, says ‘I don’t give a damn about me; I’m in love with my child.’ Apparently, parents of all genders should be denied personhood outside their children, and this is something all women want, and all men should want.

Girl Children

|

| Ashley Johnson as Shannon Dwyer in Nine Months |

Marty goes shopping for sports equipment as he’s assuring Samuel he’s having a boy, on no evidence. Apparently, all boys must be into sports, or they’ll be forced to be, and none of Marty’s daughters are athletes or could be.

When Samuel shows his distaste for being hit in the face or punched in the stomach by Marty or his daughters, Marty and the film insult Samuel’s masculinity. Especially when the daughters do it. When Marty gets into a fight with some Barney stand-in over some petty insults, Samuel doesn’t join in until he’s accused of being gay. It’s okay to be genuinely childish, apparently – like beating someone up in public over petty insults – as long as you look appropriately ‘masculine’ while doing so.

When Marty learns he’s having another girl, he complains (at the end, he relents and says, “I guess having another girl isn’t so bad.” Bravo.), and Samuel smirks about his good fortune in getting a boy. Earlier in the film, one of the reasons Samuel comes around and accepts the pregnancy is learning his child is a boy. The film obviously doesn’t value girls any more than it values women.

Samuel’s character arc is not about him overcoming his sexism – it’s about him ‘growing up’ by accepting fatherhood. When he reunites with Rebecca, he says he’s in love with his son, and is in love with her for having him – in love with her as a vessel, not a person, as Eve Kushner at Bright Lights Film Journal astutely observed. He never really misses her when she’s gone, never really asks how she’s feeling, or even has a real conversation with her – when he comes around, he comes around for the baby and not for her.

The film isn’t subverting the tropes that women, family, and children force men to lose personalities, that all women are content to be homemakers, that losing your personality is part of growing up, or that all people’s worth lies in childrearing – the film is just positively endorsing it all.

There’s nothing inherently bad about having children or getting married. One of the problems comes from the sentiment that you need a spouse and kids regardless of personal taste, or even regardless of the spouse and kids. The way many people talk about this is roughly: get a woman, or get a man, or get some kids. Any will do, apparently.

Children are not your unique children you can nurture and bond with – they’re just a burden that forces you to nobly suffer and mature. Marriage isn’t an outgrowth of a loving relationship between two complete individuals, it’s just an item on your life’s agenda to be crossed off, and establish you as an adult with a life worth living. Your spouse and children exist as objects related to you, and since that’s what you were looking for, that’s what you got.

It’s an attitude that not only reduces acceptable lifestyles down to practically nothing, but degrades the lifestyle it should be promoting. It’s a recipe for unhappy children, and unhappy marriages. Good thing Nine Months stops shortly after the nine months, and we don’t see our couple’s future. What we’ve seen – Samuel’s sullen patients, Marty and Gail’s children, as well as Marty and Gail – are evidence enough.

———-

Tyler August Adams is a Master’s candidate in Environmental Science and Policy, and writes decidedly unconventional reviews and reflections on the media at http://nevermedia.blogspot.com.