|

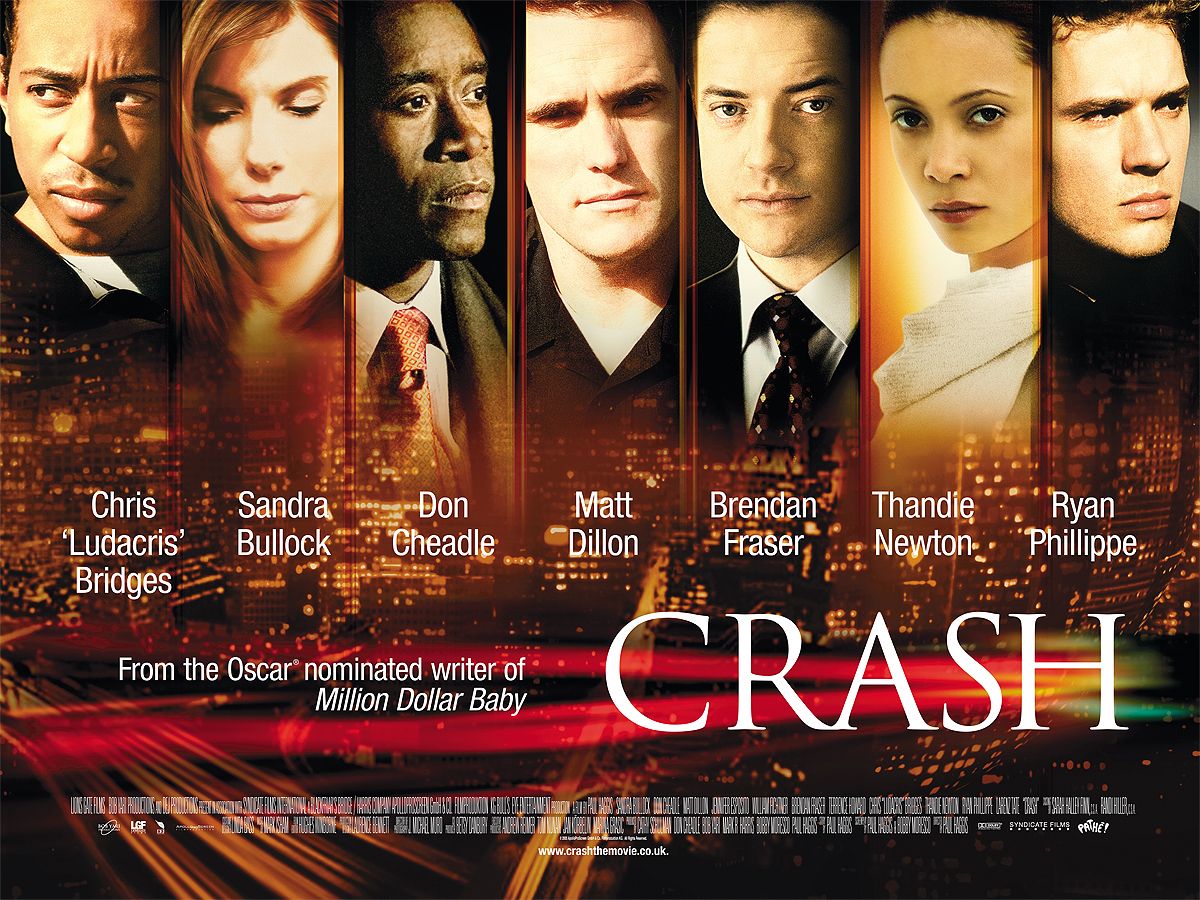

| Crash (2004) |

Author: Bitch Flicks

Women of Color in Film and TV: A Celebration of Black Women on Film in 2012

|

| Beasts of the Southern Wild |

|

| Joyful Noise |

|

| Django Unchained |

|

| Middle of Nowhere |

|

| Won’t Back Down |

“Beloved, you are my sister, you are my daughter, you are my face; you are me.” –Toni Morrison

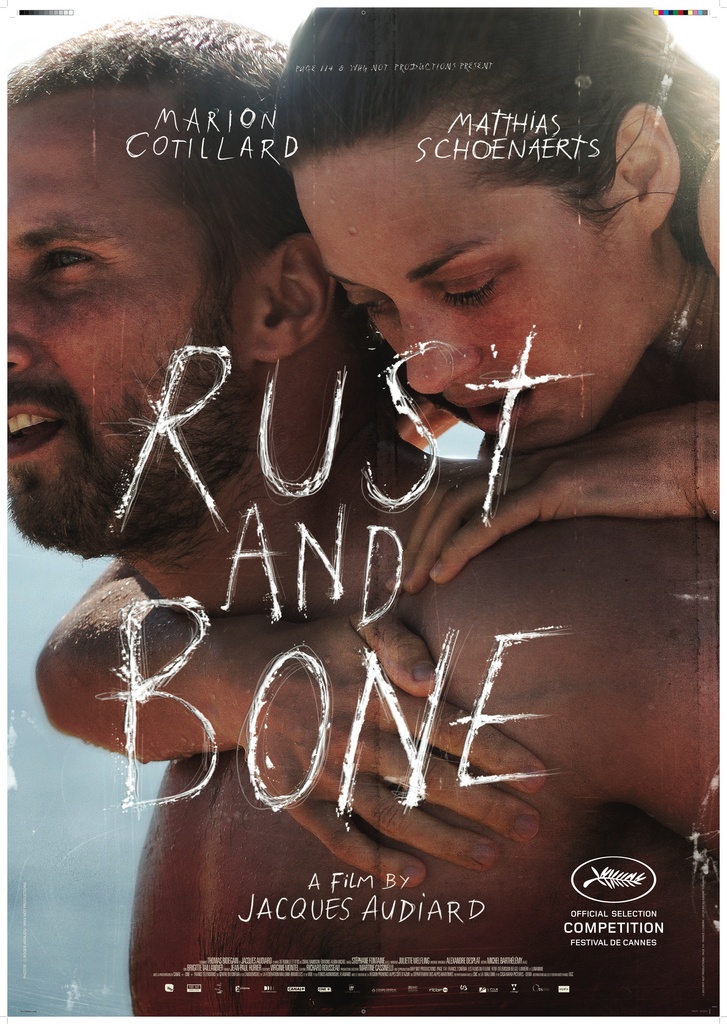

Women of Color in Film and TV: Talk About a "Scandal": ‘Bunheads,’ the Whitey-Whiteness of TV, and Why Shonda Rhimes Is a Goddamn Hero

I love Scandal. Halfway through the second season, it’s still some of the most sharp, fast-paced, thrilling TV I’ve ever sat through. Sure, it’s often improbable and features silly banter, but it’s never predictable, and Kerry Washington shines like the star she is as clever, controlled, morally ambiguous “crisis manager” Olivia Pope. (Yes, she’s the Pope.) (Oh, if only.)

What I don’t love is the fact that Kerry Washington is the first black woman to have the lead in a network drama in my lifetime.

|

| Shonda Rhimes’ Scandal |

I’m in my thirties! And since five years before I was born there hasn’t been a black female lead in an American network drama. (That was one called Get Christie Love!, inspired by the blaxploitation films of the ’70s.) And while there have been Asian and Latina leading ladies in that time, let’s not pretend that TV has ever been full of diversity. It’s a white person’s playground.

So it’s maybe not surprising that when Gilmore Girls creator Amy Sherman-Palladino’s new show Bunheads first aired, Shonda Rhimes, who created Scandal as well as Grey’s Anatomy and Private Practice, felt a little fed up.

She tweeted ABC Family:

“Really? You couldn’t cast even ONE young dancer of color so I could feel good about my kid watching this show? NOT ONE?”

Which seems like a fair comment, as Bunheads‘ lack of diversity is a glaring omission.

It’s great to see a show that’s unabashedly female-centric and more concerned with telling stories than trying to be gimmicky (and which portrays performers with far more subtlety than Smash could ever manage). There are enough shows where women are nothing more than set dressing for it not to be an issue that all six leads in Bunheads are ladies.

But it is an issue that all six leads are white.

It would have been nice if Rhimes’ tweet had launched a respectful debate about the underrepresentation of women of color on TV. Instead, it sent Sherman-Palladino on a self-justifying rant in a horrible interview with Media Mayhem, which was notable for the fact that neither she nor the journalist who questioned her actually stuck to the point. That journalist, Allison Hope Weiner, said that what she took from the incident was that it was “inappropriate” for a woman to criticise another female showrunner, when there are so few of them.

Sherman-Palladino agreed, saying she would never “go after” another woman and that women in TV are not as supportive as they should be. She also pointed out that she only had a week and a half to cast four girls who could act and dance on pointe. Then she said that she doesn’t do “issues shows.”

It’s hard to know where to start with this clusterbleep of wrongness, but how about we begin with the idea that women should always support each other, no matter what?

Rebecca Paller of the Paley Center posted a blog post about the fracas, “Bunheads and Women: Why Can’t We Just Get Along?” in which she supports Sherman-Palladino and scolds Rhimes for her criticism, saying:

“You should have been more supportive of another female showrunner especially in this day and age when it’s so difficult to get a new dramatic series on the air.”

|

| Kerry Washington as Olivia Pope in Scandal |

Saying that women have to be nice to each other at all times because there are so few of us in top jobs only promotes the idea that we’re special snowflakes who have to be treated like precious cargo. While there are men whose shows are similarly lacking in diversity, female solidarity doesn’t preclude valid criticism. And the competitiveness among women that Sherman-Palladino alludes to is surely a symptom of the patriarchy and the fact that it’s so hard for women to get ahead rather than a case of “bitches be loco.”

Even worse, for white women like Sherman-Palladino, Hope Weiner, and Paller to ignore the context of Rhimes’ remark is breathtakingly ignorant. As you might have noticed, America has a history of oppressing both women and people of color and of stereotyping them in popular culture (the Academy is still rarely more impressed than when a black women plays a maid). And yet Paller mentions a possible Asian extra as proof that Bunheads is diverse, and says she’s “still not certain” why Rhimes saw fit to criticise Sherman-Palladino.

Shonda Rhimes is one of very few TV writers creating interesting black female characters. And she’s a black woman. That’s probably not coincidental. Sure, white men could be doing the same thing. But they’re not.

|

| Kerry Washington as Olivia Pope in Scandal |

E.K.: I think the lack of diversity on Girls probably has something to do with HBO’s willingness to let her be very specific, and tell her story. Whereas with network shows, there’s always a mandate. It becomes, “How are we gonna include this group of people?” or “We have to have some diversity.”

W.C.: And then every doctor is black.

E.K.: It becomes a token gesture. It doesn’t come from a place of sincere storytelling, or anything organic to the world.

And sure, we’re talking television here, and not real life. But TV shows matter. They’re probably our biggest shared cultural experience, and how they portray (or ignore) members of historically marginalised groups can reflect and reinforce stereotypes in an insidious way. Helena Andrews wrote a great piece for xoJane about Bunheads and the fact that, had her own ballet teacher not been black, she might not have realized that the white-dominated world of dance was something she could take part in, let alone enjoy:

“In a world that was looking less and less like me just as I was beginning to actually take a look at myself (oh, hey, there puberty) seeing an impossibly elegant (and forgive me) strong black woman every week was more than just a drop in the bucket of my confidence. It was a monsoon.”

Shonda Rhimes knows it does.

———-

Women of Color in Film and TV: Talk About a ‘Scandal’: ‘Bunheads,’ the Whitey-Whiteness of TV, and Why Shonda Rhimes Is a Goddamn Hero

I love Scandal. Halfway through the second season, it’s still some of the most sharp, fast-paced, thrilling TV I’ve ever sat through. Sure, it’s often improbable and features silly banter, but it’s never predictable, and Kerry Washington shines like the star she is as clever, controlled, morally ambiguous “crisis manager” Olivia Pope. (Yes, she’s the Pope.) (Oh, if only.)

What I don’t love is the fact that Kerry Washington is the first black woman to have the lead in a network drama in my lifetime.

|

| Shonda Rhimes’ Scandal |

I’m in my thirties! And since five years before I was born there hasn’t been a black female lead in an American network drama. (That was one called Get Christie Love!, inspired by the blaxploitation films of the ’70s.) And while there have been Asian and Latina leading ladies in that time, let’s not pretend that TV has ever been full of diversity. It’s a white person’s playground.

So it’s maybe not surprising that when Gilmore Girls creator Amy Sherman-Palladino’s new show Bunheads first aired, Shonda Rhimes, who created Scandal as well as Grey’s Anatomy and Private Practice, felt a little fed up.

She tweeted ABC Family:

“Really? You couldn’t cast even ONE young dancer of color so I could feel good about my kid watching this show? NOT ONE?”

Which seems like a fair comment, as Bunheads‘ lack of diversity is a glaring omission.

It’s great to see a show that’s unabashedly female-centric and more concerned with telling stories than trying to be gimmicky (and which portrays performers with far more subtlety than Smash could ever manage). There are enough shows where women are nothing more than set dressing for it not to be an issue that all six leads in Bunheads are ladies.

But it is an issue that all six leads are white.

It would have been nice if Rhimes’ tweet had launched a respectful debate about the underrepresentation of women of color on TV. Instead, it sent Sherman-Palladino on a self-justifying rant in a horrible interview with Media Mayhem, which was notable for the fact that neither she nor the journalist who questioned her actually stuck to the point. That journalist, Allison Hope Weiner, said that what she took from the incident was that it was “inappropriate” for a woman to criticise another female showrunner, when there are so few of them.

Sherman-Palladino agreed, saying she would never “go after” another woman and that women in TV are not as supportive as they should be. She also pointed out that she only had a week and a half to cast four girls who could act and dance on pointe. Then she said that she doesn’t do “issues shows.”

It’s hard to know where to start with this clusterbleep of wrongness, but how about we begin with the idea that women should always support each other, no matter what?

Rebecca Paller of the Paley Center posted a blog post about the fracas, “Bunheads and Women: Why Can’t We Just Get Along?” in which she supports Sherman-Palladino and scolds Rhimes for her criticism, saying:

“You should have been more supportive of another female showrunner especially in this day and age when it’s so difficult to get a new dramatic series on the air.”

|

| Kerry Washington as Olivia Pope in Scandal |

Saying that women have to be nice to each other at all times because there are so few of us in top jobs only promotes the idea that we’re special snowflakes who have to be treated like precious cargo. While there are men whose shows are similarly lacking in diversity, female solidarity doesn’t preclude valid criticism. And the competitiveness among women that Sherman-Palladino alludes to is surely a symptom of the patriarchy and the fact that it’s so hard for women to get ahead rather than a case of “bitches be loco.”

Even worse, for white women like Sherman-Palladino, Hope Weiner, and Paller to ignore the context of Rhimes’ remark is breathtakingly ignorant. As you might have noticed, America has a history of oppressing both women and people of color and of stereotyping them in popular culture (the Academy is still rarely more impressed than when a black women plays a maid). And yet Paller mentions a possible Asian extra as proof that Bunheads is diverse, and says she’s “still not certain” why Rhimes saw fit to criticise Sherman-Palladino.

Shonda Rhimes is one of very few TV writers creating interesting black female characters. And she’s a black woman. That’s probably not coincidental. Sure, white men could be doing the same thing. But they’re not.

|

| Kerry Washington as Olivia Pope in Scandal |

E.K.: I think the lack of diversity on Girls probably has something to do with HBO’s willingness to let her be very specific, and tell her story. Whereas with network shows, there’s always a mandate. It becomes, “How are we gonna include this group of people?” or “We have to have some diversity.”

W.C.: And then every doctor is black.

E.K.: It becomes a token gesture. It doesn’t come from a place of sincere storytelling, or anything organic to the world.

And sure, we’re talking television here, and not real life. But TV shows matter. They’re probably our biggest shared cultural experience, and how they portray (or ignore) members of historically marginalised groups can reflect and reinforce stereotypes in an insidious way. Helena Andrews wrote a great piece for xoJane about Bunheads and the fact that, had her own ballet teacher not been black, she might not have realized that the white-dominated world of dance was something she could take part in, let alone enjoy:

“In a world that was looking less and less like me just as I was beginning to actually take a look at myself (oh, hey, there puberty) seeing an impossibly elegant (and forgive me) strong black woman every week was more than just a drop in the bucket of my confidence. It was a monsoon.”

Shonda Rhimes knows it does.

———-

Women of Color in Film and TV: The Terrible, Awful Sweetness of ‘The Help’

|

| Mmm…empty calories. Like The Help? |

The perfect summer escape for viewers who embrace the fantasy of a postracial America, [where] filmgoers can tuck the history of race and class inequality safely in the past, even as the recession deepens already profound racial gaps in wealth and employment.

Women of Color in Film and TV: ‘Scandal’ Pilot: Loosen Up Your Buttons, Baby

|

| Scandal |

The setup is complete by the end of Scene 5. Everything and everyone we need to know has been established. Now the story is about to get moving. A disabled, Iraq war hero appears in the office lobby with blood on his hands. “My girlfriend. She’s dead,” he says. “And the police think I killed her.” In a comic book, the exclamation point follows the BANG! In this scene, the gun has already gone off and we are seeing the effects of the aftermath. Harrison turns to Quinn and says, “Welcome to Pope and Associates!”

Women of Color in Film and TV: ‘Pariah’

|

| Pariah (2011), a film by Dee Rees |

An astounding, vibrant piece of finely weaved storytelling and thoughtfully spoken artistry, this independent film centers on Brooklyn high school teen, Alike (pronounced ah-lik-e) an exceptionally good student and aspiring poet from a hard-working middle-class family. In her underground world, the shy girl hangs out with bold, outspoken, Laura, who has already proudly come out and lives with her sister.

|

| Bina (Aasha Davis) and Alike (Oduye) in the stages of love |

|

| Alike with Audrey (Kim Wayans) during happier times |

|

| Alike and Arthur (Charles Parnell) after that horrible scene |

|

| Sharonda loves her sister no matter what! |

|

| The lovely, talented Adepero Oduye |

|

| Laura trying to change up Alike’s fashion sense! |

|

| Actress Adepero Oduye, Pariah writer/director Dee Rees, and Actress Kim Wayans |

———-

Janyce Denise Glasper is a writer/artist running two silly blogs of creative adventures called Sugarygingersnap and AfroVeganChick. She enjoys good female-centric film, cute rubber duckies, chocolate covered everything (except bugs!), Days of Our Lives, and slaying nightly demons Buffy style in Dayton, Ohio.

Women of Color in Film and TV: Thoughts on ‘The Mindy Project’ and Other Screen Depictions of Indian Women

|

| The Mindy Project |

|

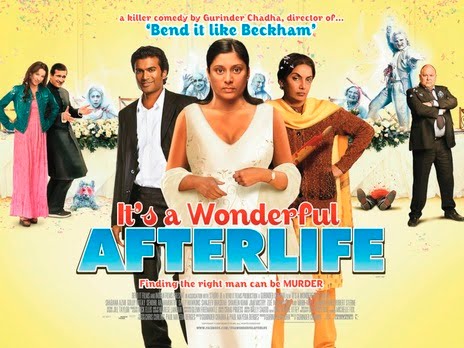

| Gurinder Chadha’s It’s a Wonderful Afterlife |

|

| The women of Monsoon Wedding, directed by Mira Nair |

|

| #themindyproject |

|

| “I just need to ride out this minor humiliation until I find my Kanye.” |

|

| “It’s so weird being my own role model.” |

|

| Mindy Kaling as Mindy Lahiri |

———-

Women of Color in Film and TV: ‘Sparkle:’ Same Song, Fine Tuned

|

| The three sisters of ‘Sparkle’ (2012) |

Guest post written by Candice Frederick, originally published at Reel Talk. Cross-posted with permission.

|

| Salim Akil’s Sparkle revisits the Motown era |

But right at the height of a promising career, life throws them some curve balls. Sister, always looking for the next quick and easy (and lucrative) opportunity, meets and falls hard for the “coon” comedian extraordinaire Satin (Mike Epps). She quickly gets entangled in his lies, deceit and utter immoralities and spirals downwards, taking her sisters’ singing group down with her. That is, until Sparkle finds the voice she’d kept hidden for so long, which will carry her to the next phase of her life and shine like she always dreamed she would.

|

| Sparks as Sparkle in ‘Sparkle.’ Clear? |

Admittedly, Sparkle‘s storyline is the one cliched and predictable element carried over from the original movie. Sparks gives a fine performance but, like Irene Cara before her, doesn’t have much to work with and her real-life singing voice provides the most memorable scenes in her performance. What’s not so expected in this re-imagining is the heightened point of view of the other characters in the story. Emma, the girls’ mom, isn’t just a wise older woman with little dialogue but who dutifully captures the parental element of the story, as she is in the original film. Emma is now a very present mother in the story, someone who rules her house with a sharp but loving tongue, and one who is quick to recite passages from Scripture to remind her daughters of who’s really in control. Emma is also a “cautionary” character, as she herself alludes to but is careful not to define in the movie (as delivered in an eerily familiar and poignant performance by the late Houston). She is heavily nuanced and delicately penned by screenwriters Mara Brock Akil (TV’s Girlfriends and The Game) and Harry Rosenman (Father of the Bride, The Family Man).

|

| The late Whitney Houston as mother Emma |

Also fine tuned for a razor-sharp performance is the role of Sister. She was always the most complicated character of the bunch, formerly played by the eternally underrated actress Lonette McKee (in one of her best roles). While Ejogo’s portrayal almost mirrors that of McKee’s (which is high praise), Sister doesn’t come across as similarly damaged as she did in the previous movie. She settles on a rather mature consequence for decisions she’s made, which in turn allows her character to linger just a bit longer here, and leave a lasting impression on the audience.

|

| Sister, played by Carmen Ejogo |

Another unforgettable character portrayal is that of D played by Sumpter. If you’ve seen the original film, you might not even remember much of anything substantial about this third sister, except that she was her mother’s mute pride and joy. She was the one with the bright future whose feelings about the whole music thing is, as she further explains in this movie, are that she can “really take or leave it.” This remake does a better job at explaining a lot more behind her actions–i.e. why she’s more fearless than her other sisters in a lot of ways (she really has nothing here to lose) and why she won’t sacrifice everything for someone else’s dream. Sumpter, with help from the screenplay, gives D a backbone, a steel tongue to deliver the film’s wittiest and most entertaining dialogue that will cut through even the most dramatic scenes. Sparkle might have been the character in search of a voice, but it is D whose voice had become magnified and clearer.

| D, played by Tika Sumpter |

Epps also gives a surprisingly good performance here as well. And he’s got a lot to work with. Satin isn’t just the fleeting bad guy who comes to terrorize the Sister and her Sisters trio. He’s definitely not a guy you root for, but there is more to his story here. He has much more purpose. Epps sheds his comedic image to possibly play the role of his career, but uses some of that comedian swagger in a way that complements Satin’s own demons. Meanwhile, the other fellas in the cast, Luke and Omari Hardwick (who plays Levi, Sister’s jilted ex) contribute good–however serviceable–portrayals in an overwhelmingly female-driven movie.

———-

Women of Color in Film and TV: ‘Sparkle’: Same Song, Fine Tuned

|

| The three sisters of ‘Sparkle’ (2012) |

Guest post written by Candice Frederick, originally published at Reel Talk. Cross-posted with permission.

|

| Salim Akil’s Sparkle revisits the Motown era |

But right at the height of a promising career, life throws them some curve balls. Sister, always looking for the next quick and easy (and lucrative) opportunity, meets and falls hard for the “coon” comedian extraordinaire Satin (Mike Epps). She quickly gets entangled in his lies, deceit and utter immoralities and spirals downwards, taking her sisters’ singing group down with her. That is, until Sparkle finds the voice she’d kept hidden for so long, which will carry her to the next phase of her life and shine like she always dreamed she would.

|

| Sparks as Sparkle in ‘Sparkle.’ Clear? |

Admittedly, Sparkle‘s storyline is the one cliched and predictable element carried over from the original movie. Sparks gives a fine performance but, like Irene Cara before her, doesn’t have much to work with and her real-life singing voice provides the most memorable scenes in her performance. What’s not so expected in this re-imagining is the heightened point of view of the other characters in the story. Emma, the girls’ mom, isn’t just a wise older woman with little dialogue but who dutifully captures the parental element of the story, as she is in the original film. Emma is now a very present mother in the story, someone who rules her house with a sharp but loving tongue, and one who is quick to recite passages from Scripture to remind her daughters of who’s really in control. Emma is also a “cautionary” character, as she herself alludes to but is careful not to define in the movie (as delivered in an eerily familiar and poignant performance by the late Houston). She is heavily nuanced and delicately penned by screenwriters Mara Brock Akil (TV’s Girlfriends and The Game) and Harry Rosenman (Father of the Bride, The Family Man).

|

| The late Whitney Houston as mother Emma |

Also fine tuned for a razor-sharp performance is the role of Sister. She was always the most complicated character of the bunch, formerly played by the eternally underrated actress Lonette McKee (in one of her best roles). While Ejogo’s portrayal almost mirrors that of McKee’s (which is high praise), Sister doesn’t come across as similarly damaged as she did in the previous movie. She settles on a rather mature consequence for decisions she’s made, which in turn allows her character to linger just a bit longer here, and leave a lasting impression on the audience.

|

| Sister, played by Carmen Ejogo |

Another unforgettable character portrayal is that of D played by Sumpter. If you’ve seen the original film, you might not even remember much of anything substantial about this third sister, except that she was her mother’s mute pride and joy. She was the one with the bright future whose feelings about the whole music thing is, as she further explains in this movie, are that she can “really take or leave it.” This remake does a better job at explaining a lot more behind her actions–i.e. why she’s more fearless than her other sisters in a lot of ways (she really has nothing here to lose) and why she won’t sacrifice everything for someone else’s dream. Sumpter, with help from the screenplay, gives D a backbone, a steel tongue to deliver the film’s wittiest and most entertaining dialogue that will cut through even the most dramatic scenes. Sparkle might have been the character in search of a voice, but it is D whose voice had become magnified and clearer.

| D, played by Tika Sumpter |

Epps also gives a surprisingly good performance here as well. And he’s got a lot to work with. Satin isn’t just the fleeting bad guy who comes to terrorize the Sister and her Sisters trio. He’s definitely not a guy you root for, but there is more to his story here. He has much more purpose. Epps sheds his comedic image to possibly play the role of his career, but uses some of that comedian swagger in a way that complements Satin’s own demons. Meanwhile, the other fellas in the cast, Luke and Omari Hardwick (who plays Levi, Sister’s jilted ex) contribute good–however serviceable–portrayals in an overwhelmingly female-driven movie.

———-

Women of Color in Film and TV: Mammy, Sapphire, or Jezebel, Olivia Pope is Not: A Review of ‘Scandal’

|

| Scandal, created by Shonda Rimes and starring Kerry Washington |